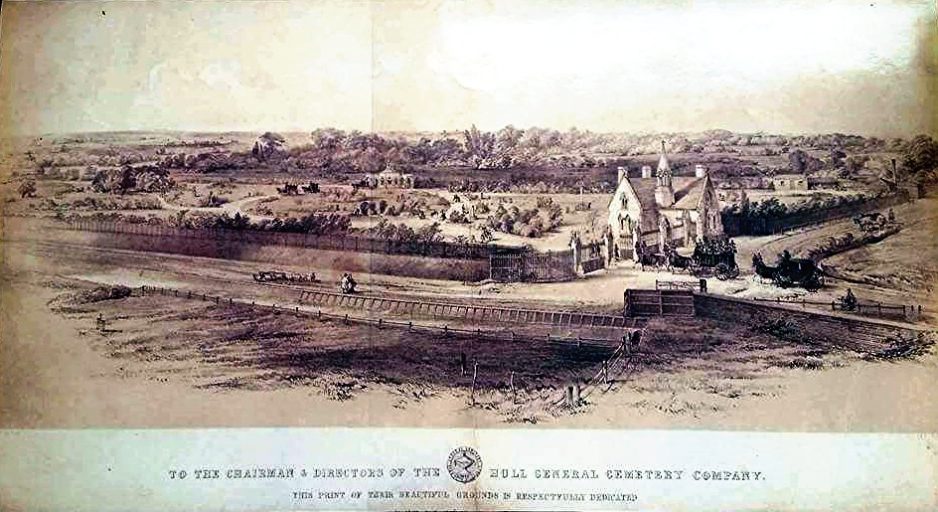

Edward Nequest was part of a very select group of people. There were only four superintendents of Hull General Cemetery.

John Shields was the first. He and Cuthbert Brodrick laid out the paths and plots of the cemetery prior to its opening in 1847. John Shields died suddenly in 1866. He was succeeded by Edward. He himself retired in 1891. Michael Kelly took over until 1944. After that Michael’s daughter Cicely Kelly continued in this post until her enforced retirement in the 1950s. There were no more superintendents.

Edward’s birth

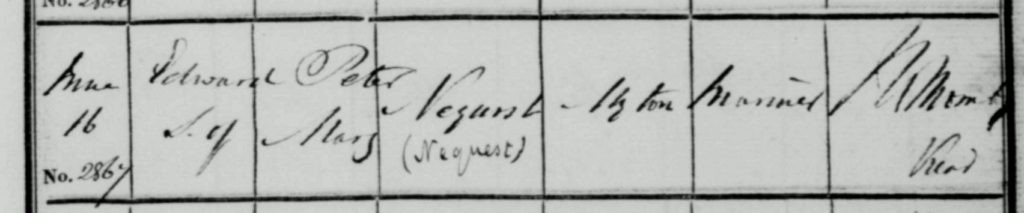

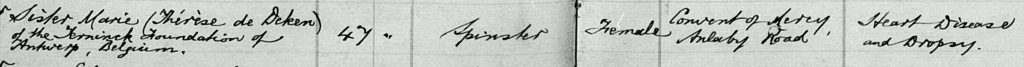

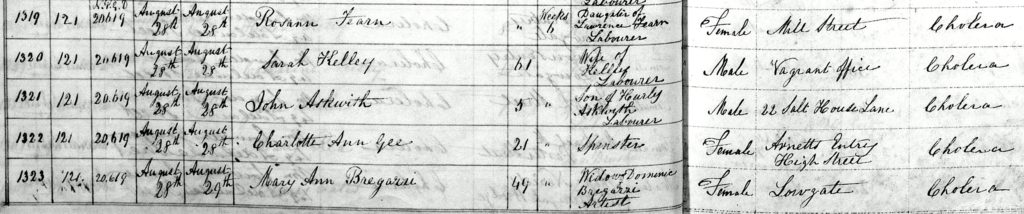

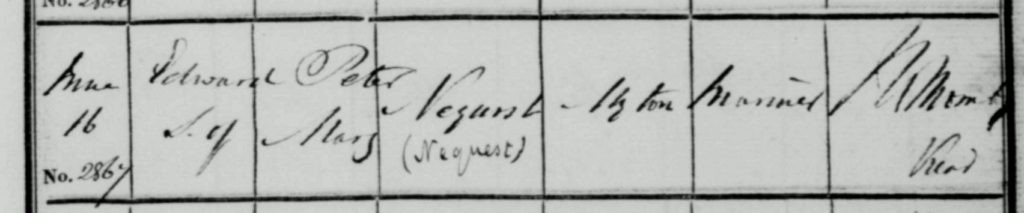

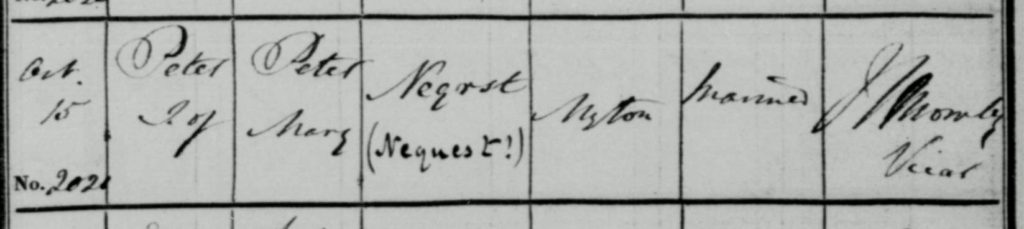

Edward Nequest was born in Hull in 1823. The image below shows his baptism at Holy Trinity that year.

In the second column below, which may be difficult to read, the name Edward is inserted. This is followed by ‘S of’ denoting ‘son of’. The registrar also had difficult with the surname. The correction is in brackets. Edward’s parents were Peter and Mary. Their address is given as Myton and the father’s occupation is recorded as a mariner. The incumbent of Holy Trinity at the time was John Bromby.

This vicar had the longest tenure of any incumbent of this parish. He became the vicar of Holy Trinity in 1797 and stepped down from the post in 1867 after 70 years service. He died the following year and is buried in the churchyard of North Ferriby.

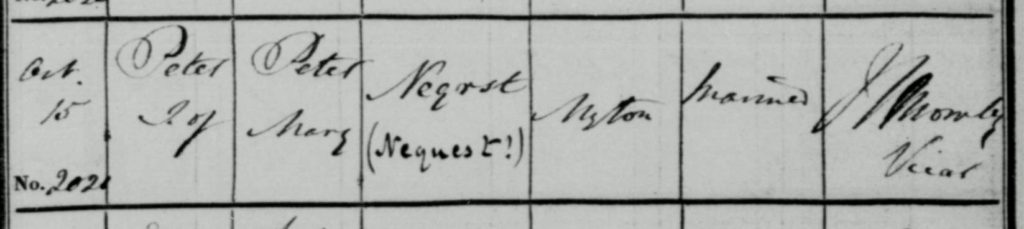

Edward was the second son from this marriage. The first son was also called Peter and he was born in 1821 and baptised at the same church.

Home

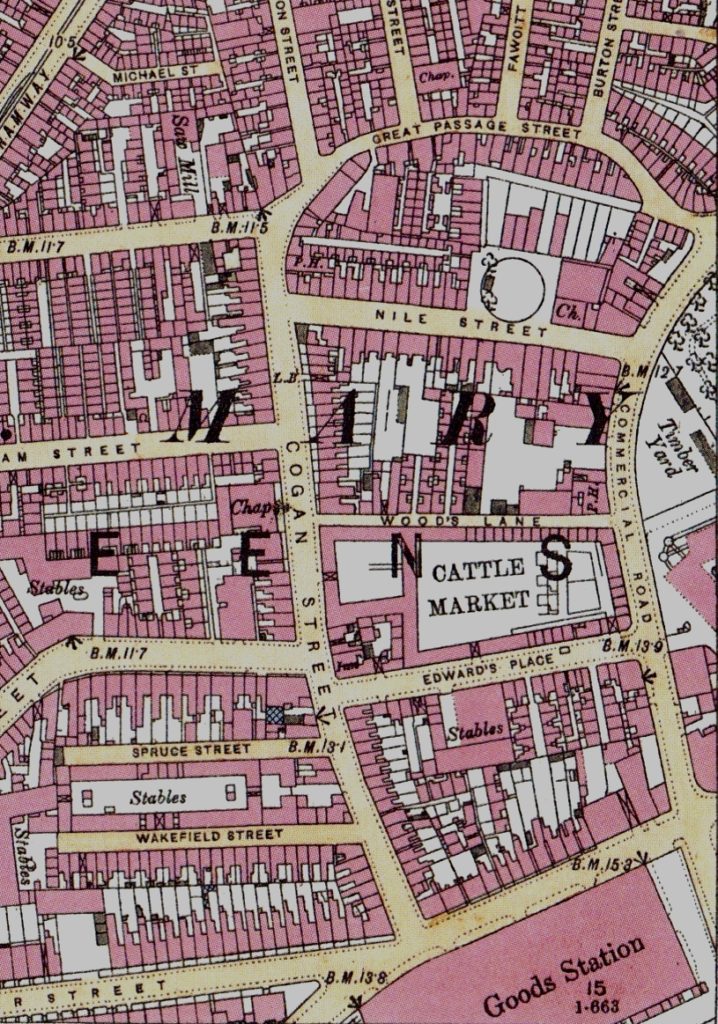

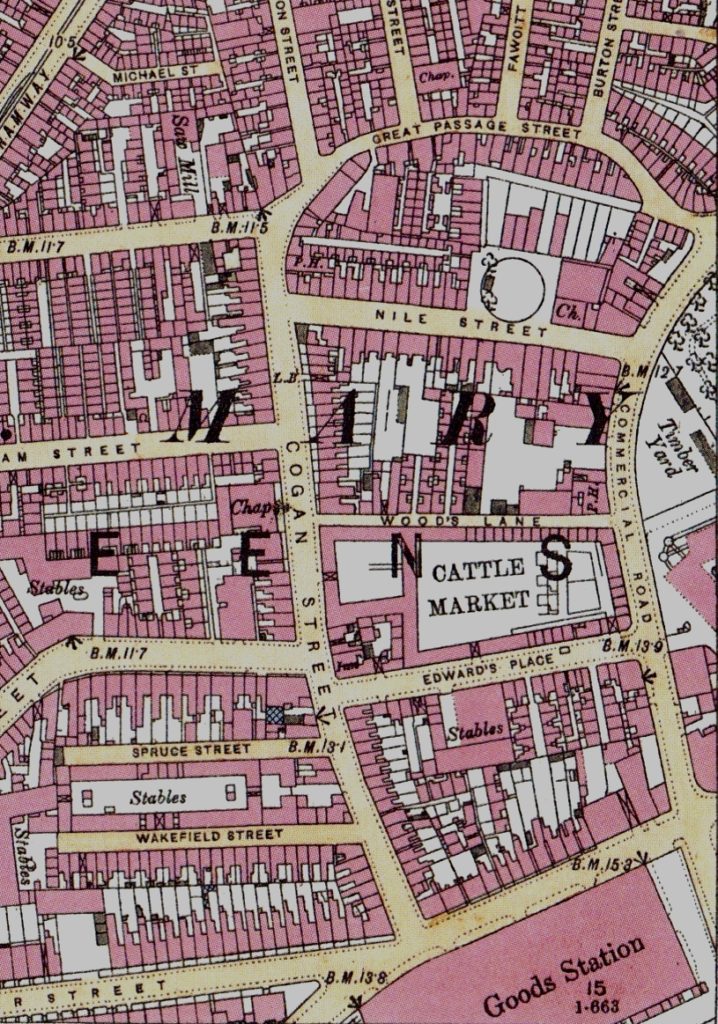

We have no idea of where the Nequest family lived at this time but by the 1841 census we know the family lived in Cogan Street. It still exists but in a truncated form. Clive Sullivan Way now occupies the southern part where Cogan Street stood.

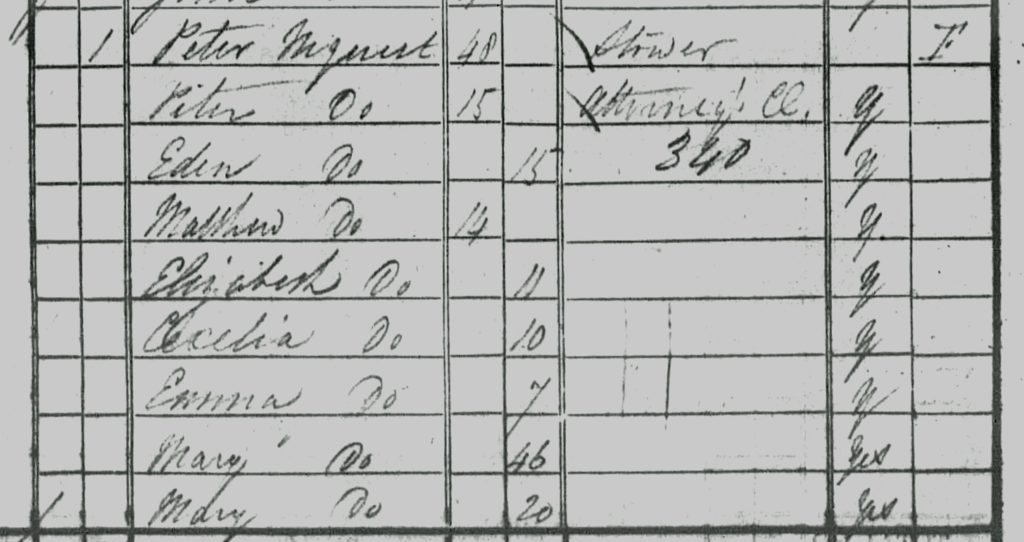

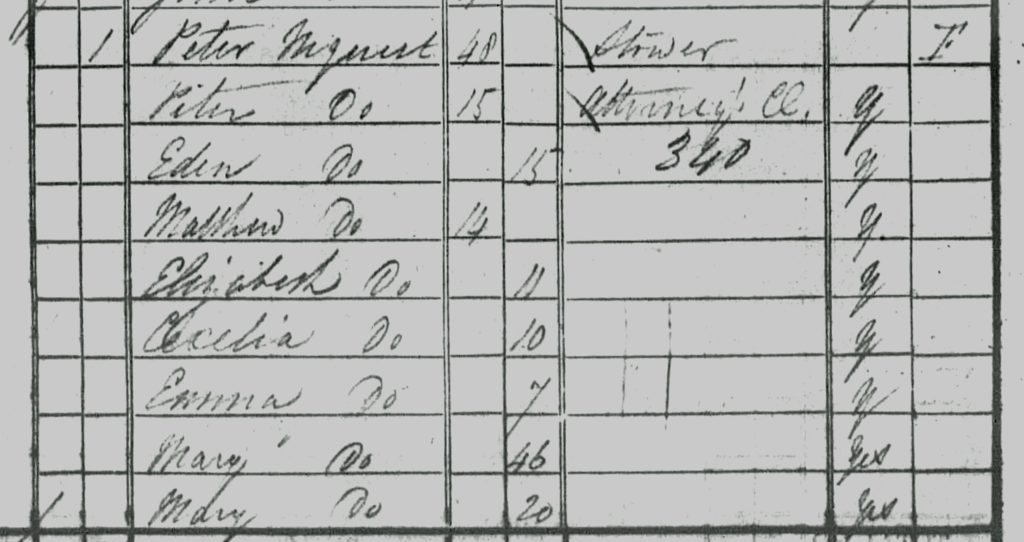

In the 1841 census of Peter Nequest we find him listed as a ‘Stower’, and his wife, Mary, is strangely placed near the end of the family listing. The 1841 census generally is a blunt tool in comparison with later ones. It often rounded the ages of children up or down to the nearest five yearly span. We find that in the 1841 Nequest census both of Peter’s sons’ ages, Peter and Edward, are given as 15 yet Peter would have been 20 and Edward 18 at the time. The younger Peter, as you can see, is listed as an attorney’s clerk. Edward was soon to follow his brother into this profession.

You may also see that Peter the elder has an ‘F’ against his name. That is because he was born in Sweden in 1793 and migrated to Hull. We have no information why he did this. A shrewd guess would be that it may have been due to the Napoleonic Wars and the British blockade of the continent at the time. A mariner would have found work difficult at that time and emigrating to Britain was a way out of this dilemma.

1851 census

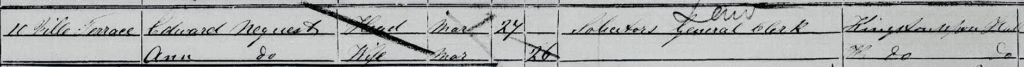

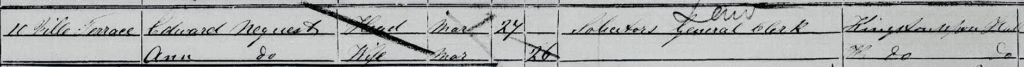

By the time of the 1851 census Edward has moved from the family home. He now lived in a small terrace called Ville Terrace off the newly laid out Hessle Road not far from no1. Hessle Road.

Perhaps more importantly for Edward was that he now was married. He had married Ann Plaxton in 1849. He was also a solicitor’s clerk.

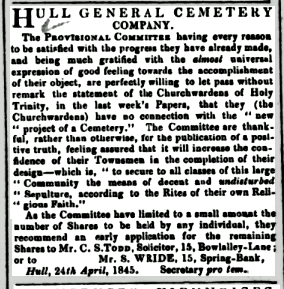

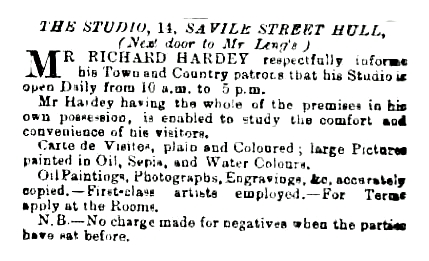

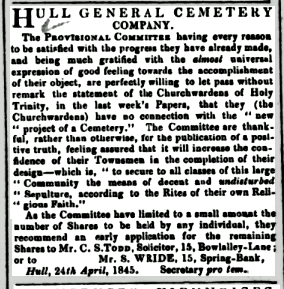

Not just any solicitor. He was apprenticed and articled to one of the most famous solicitors in Hull. His employer was Charles Spilman Todd. This man had been instrumental in carrying through the purchase of the cemetery’s grounds. Indeed the first meeting of the provisional committee took place in his office at no.15 Bowlalley Lane.

C.S.Todd as he was known was both the solicitor and secretary for the Company and also was a large shareholder. Still later in his life he was a councillor and became the secretary for the Local Board of Health and eventually he was elected as Sheriff of Hull. The Creation of Hull General Cemetery: Part Two

Shadrach Wride

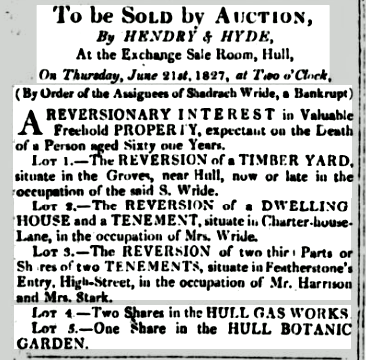

In the 1840s the first secretary to C.S.Todd was a man called Shadrach Wride. This man is worthy of an article himself.

Baptised in 1796 in Holy Trinity the year before Rev. Bromby took over. Shadrach was the son of a man of the same name. This man had been the foreman of Jackson’s wood yard in the Groves and he ‘luckily’ married the bosses’ daughter. When he died in 1823 he left the business to his son. Whether the business was in a good state or worth anything is open to question.

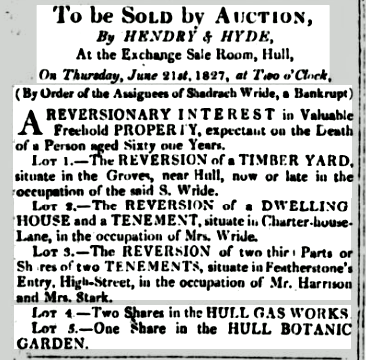

Sadly the business failed in 1827 and Shadrach Wride entered the Bankruptcy Court. The timber yard was auctioned off. Even the family home on Charterhouse Lane had to be sold.

Debtor’s prison

One has to remember the draconian laws then regarding debts. Today a person who becomes bankrupt can have that burden discharged after two or three years whilst not paying their debts. Not so in Georgian and Victorian times. Charles Dickens’s father was a debtor and was placed in Marshalsea Prison until the debt was repaid. Dickens himself had to work in a blacking factory to help pay this debt at the tender age of 12. This had a marked effect upon the young boy and it came out in his works in later life.

Little Dorrit is almost completely set inside a debtor’s prison. Nicholas Nickelby, Great Expectations and Pickwick Papers all allude or feature the stigma of the debtor’s prison. Shadrach Wride would have used all in his power to avoid being imprisoned for this ‘crime’. That he did so, and was later rehabilitated says a great deal about the man.

Rebuilding his life

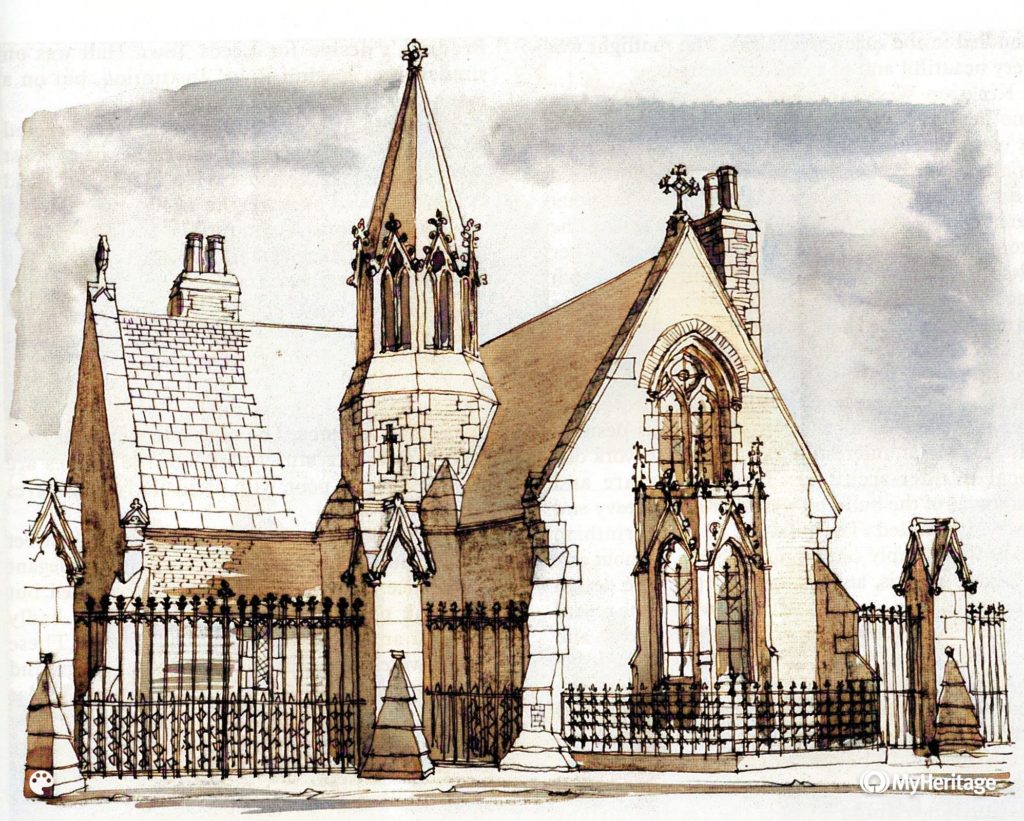

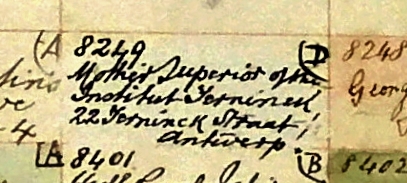

After this date Shadrach contented himself in making ends meet by taking on a number of roles. Often cited as an agent for insurance companies and emigration agencies he was still a respected member of society. He was the secretary for the Fish street Church and was part of that committee until his death. His abode was at 15 Spring Bank, on the corner of Spring Street, and this address was often used as a postal address for the Cemetery before the lodge was built.

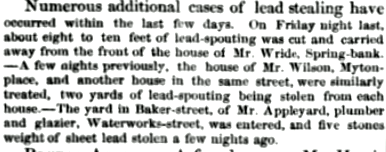

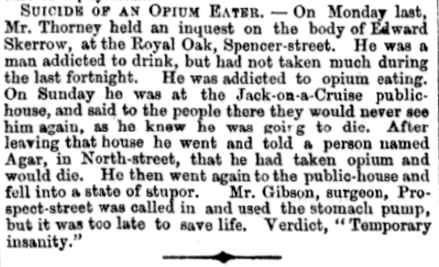

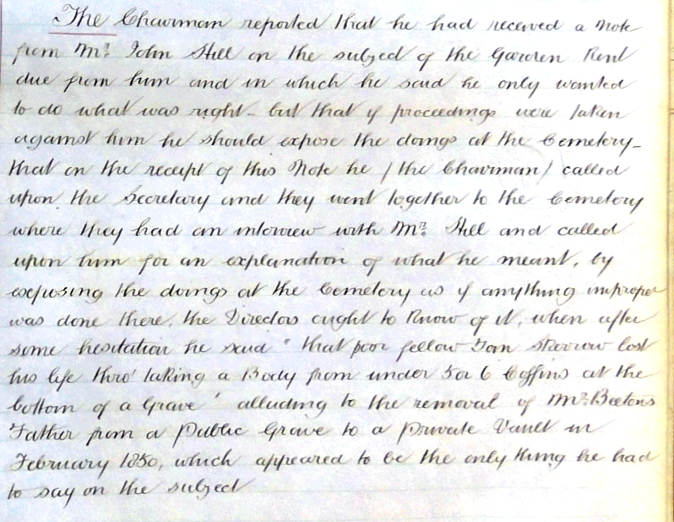

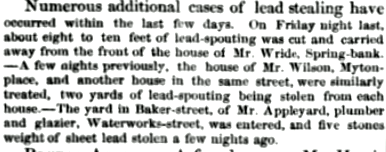

To show that the ‘Good Old Days’ never really existed the newspaper item below perhaps shows that modern life is typical of what went before.

Mr Wride was also the secretary for the C.S.Todd’s legal practice and therefore the secretary for the Company. The evidence for this is often to be found in the newspapers of the time but also in the records of the Company that still exist.

Shadrach Wride was also listed as the Company secretary on the brass plate that was buried in the foundations of the Lodge at the official opening of the Cemetery in June 1847.

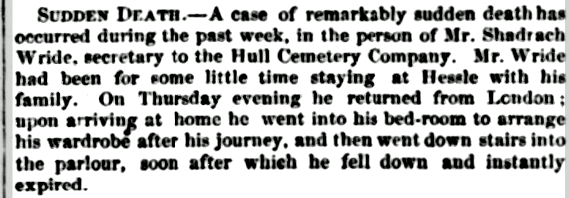

Wride’s death

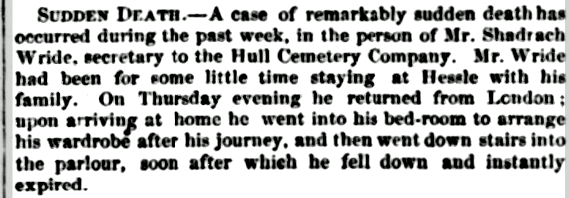

So the man’s death came as a shock to many parties. Shadrach died on July 25th 1850 as the news item below shows.

He is buried in Hull General Cemetery in compartment 35 only two grave spaces away from his employer C.S.Todd’s own grave. the cause of death is cited as apoplexy. The vacancy he left was filled by Edward Nequest.

Edward’s work

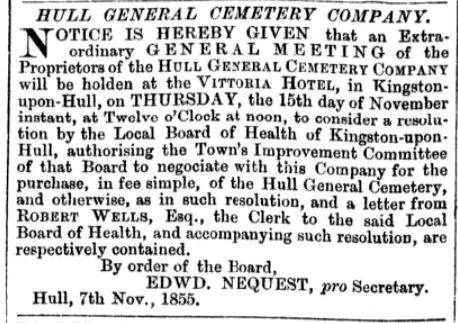

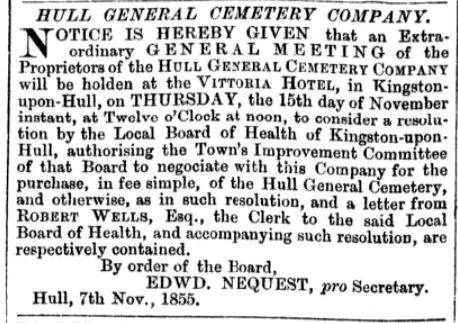

The first we learn of Edward’s new appointment is once again via the local newspaper. This is some five years after Wride’s death. It is obvious that Edward is not taking things for granted, signing himself as pro secretary. The term ‘pro‘ here is standing for pro tem, meaning for the time being. There were no chickens being counted too early here.

By the following March, in a further newspaper item, Edward signs himself as the secretary, so his appointment must have been confirmed.

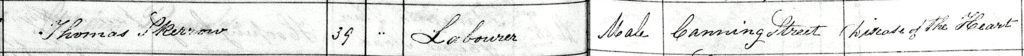

However whether any such appointment was ever confirmed is open to doubt. Shadrach Wride’s occupation given in the Cemetery’s burial register is ‘agent to the life insurance company‘ even though he had been both C.S.Todd and the Company secretary for at least five years. Edward, when he bought graves in the Cemetery, is listed as ‘Attorney’s clerk’ and this terminology lasted until the mid 1860s. It appears that the Company didn’t like to be tied down.

Domestic issues

But we are getting ahead of ourselves a bit here. Edward, as we know, was a family man and the domestic side of his life needs some explaining. Or at least an attempt should be made for there is one aspect that is a mystery.

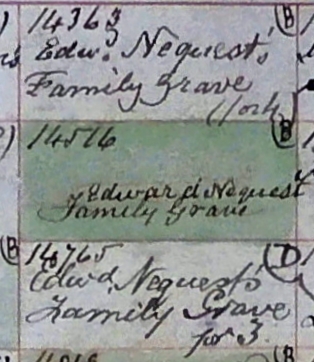

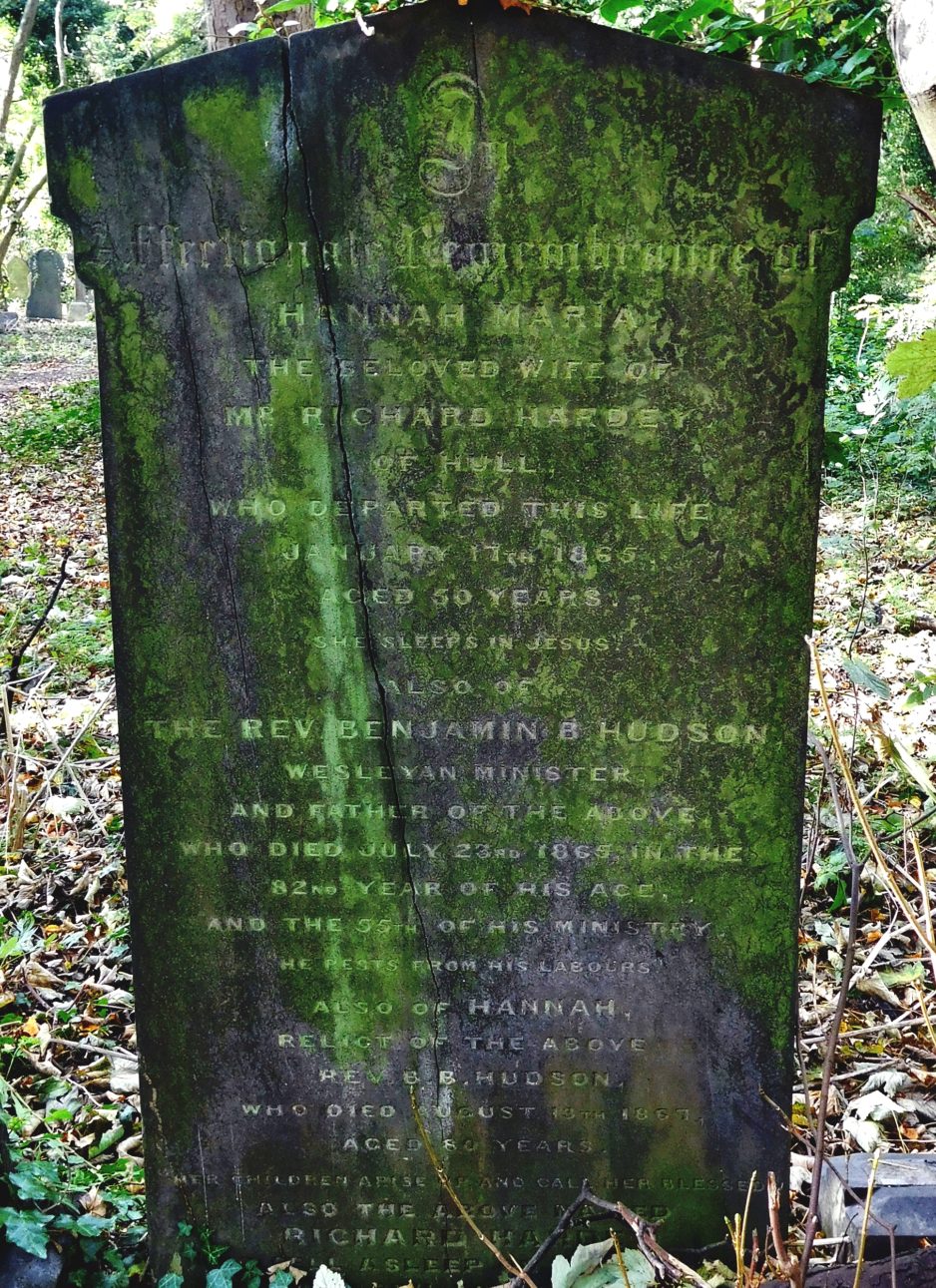

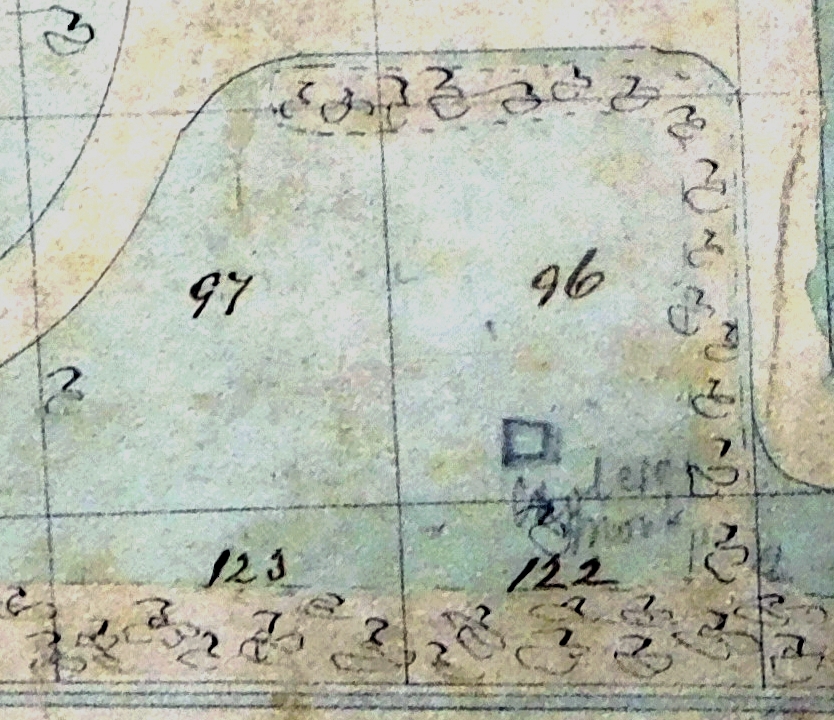

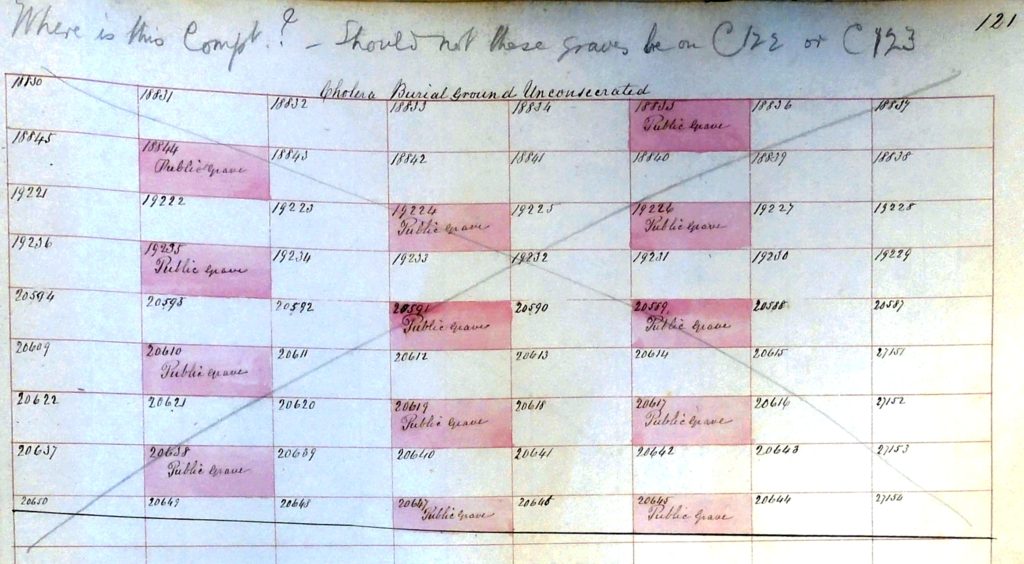

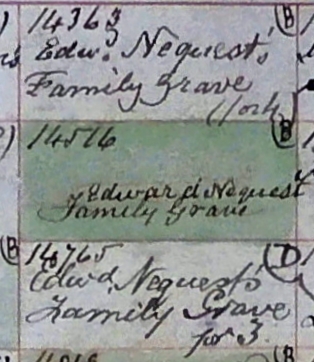

Edward Nequest owned three graves in Hull General Cemetery. They are in compartment 105 close to the south side of the cemetery.

Whether he bought them all at the same time is debateable. What we do know was that the first purchase took place in 1850 for on the 3rd October the first burial took place within it. This was of a young girl, Jane Bell. This child was the daughter of ‘the late Robert Bell, Customs Officer’. I have struggled to find a family connection but in vain. The only supposition I have come up with is that Robert Bell may have been a friend and neighbour as the address given is Elizabeth Place, Hessle Road. This was very near to Edward’s own address at the time. I’m afraid this tenuous link is the best I can do.

1861

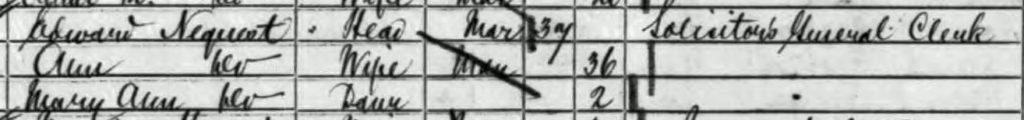

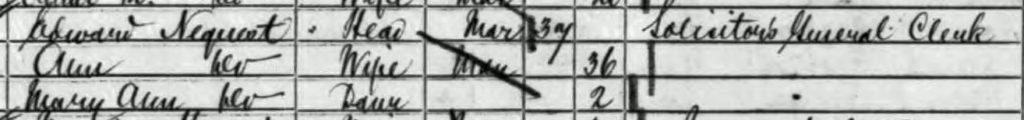

By the time of the 1861 census Edward had moved house. He now lived at a house in Porter Street with his wife and young daughter Mary Ann.

Sadly, only 2 years later, in the July of 1863, this child was the second burial in this plot. Measles and consumption of the bowels was the cause of death.

Becoming superintendent

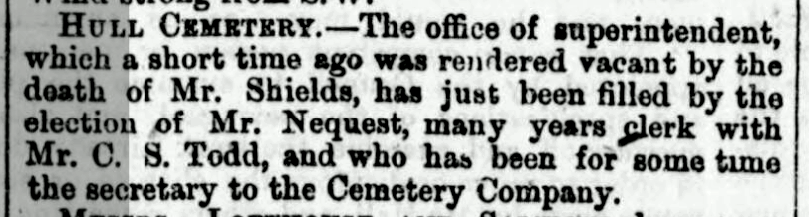

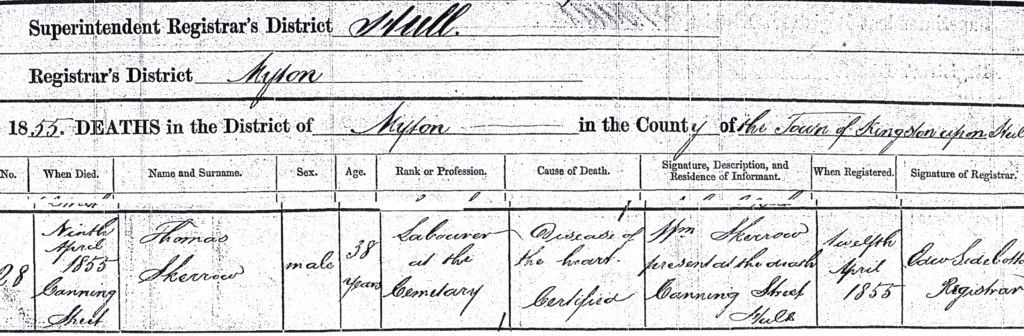

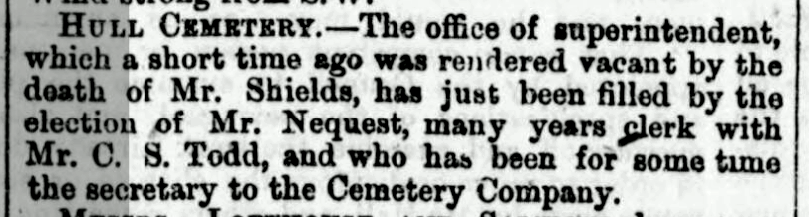

In November 1866 John Shields, the first superintendent passed away suddenly. In the following January the Board appointed Edward Nequest to the post of superintendent.

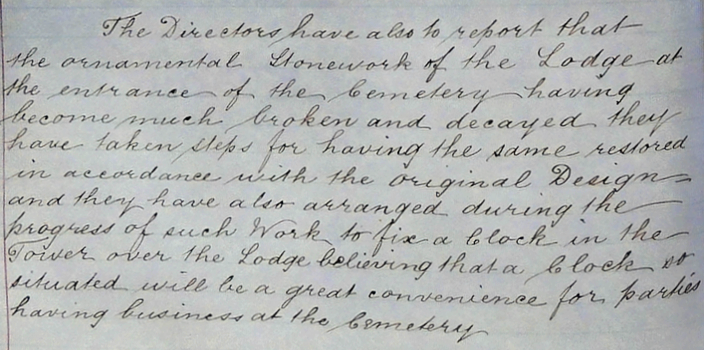

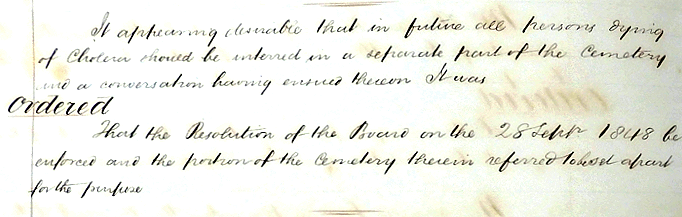

They also decided, short-sightedly, to combine the roles of superintendent and secretary. Seemingly implemented as a cost-cutting measure it alienated their solicitor, the fore-mentioned C.S.Todd who resigned from the Board. When he became the secretary to the Local Board of Health this alienation came back to bite the Company but that is another story. An Anniversary

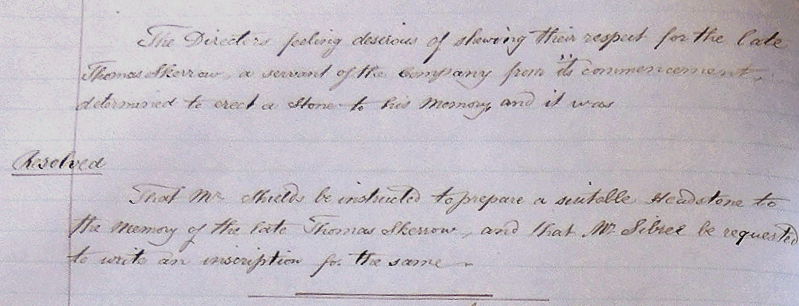

The minute books

The minute books of the Company record this decision.

‘Special meeting of directors 20/12/66. Present Irving, Bell and Oldham

‘The vacancy occasioned by the death of Mr S. the late superintendent again came under consideration of the board when the question as to the desirability of amalgamating the two offices of secretary and supt., was discussed and it was ultimately unanimously resolved that in the opinion of the board, the time has now arrived when it seems desirable that the two offices of sec., and supt., may be advantageously combined.

It was further resolved that a copy of the foregoing resolution be handed to C.S.Todd esq, the secretary and that the directors have an early interview with him on the subject. The necessity of filling up the vacancy occasioned by Mr. Shield’s death having been discussed and an application for the office received from Mr Nequest having been considered it was unanimously resolved that taking into consideration Mr Nequest’s long and satisfactory connection with the company the situation of supt., and registrar be offered to him at the salary of £110 per annum with the use of the lodge and this his duties to commence on Tuesday the first of January 1867.’

This appointment was recorded in the local press.

A Company Man

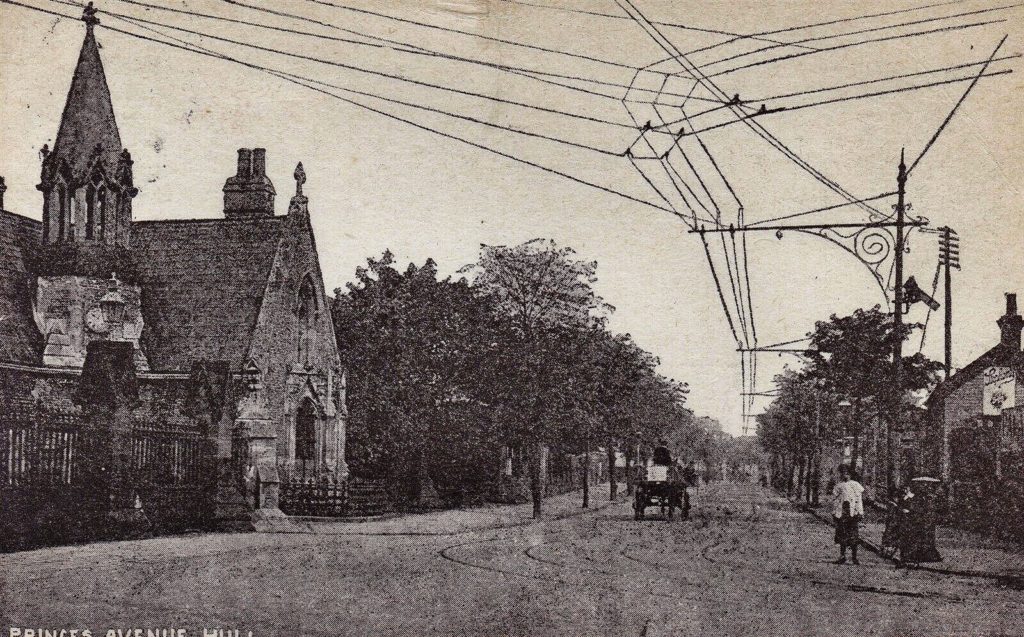

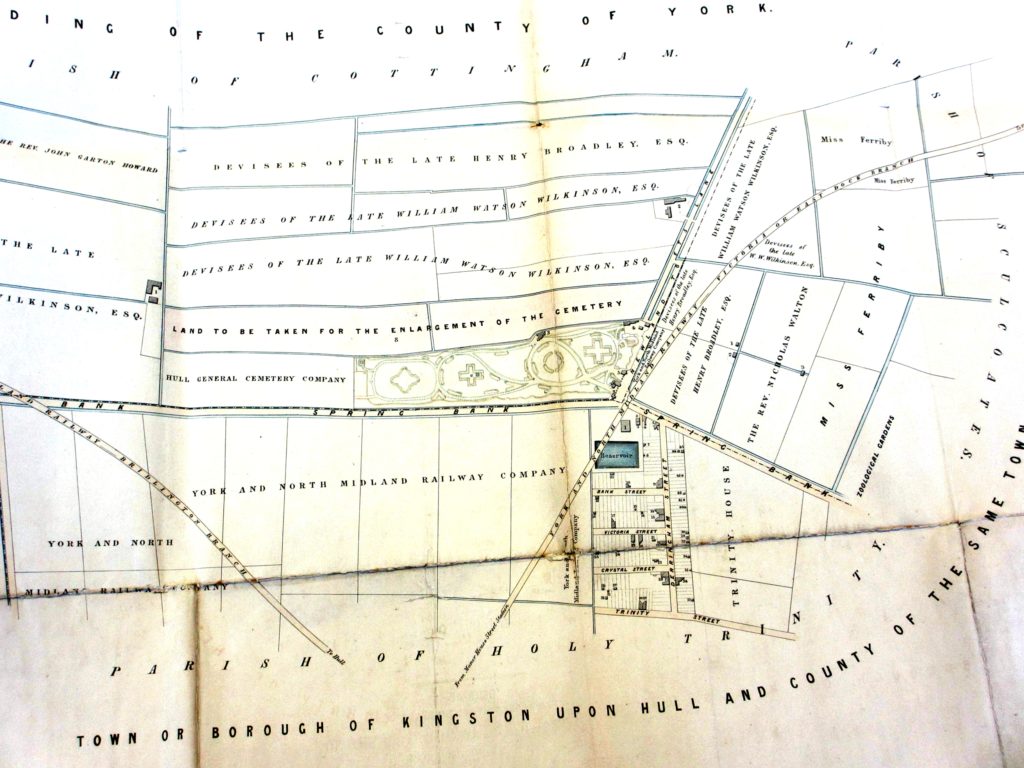

It’s fair to say that Edward threw himself into his work, much like John Shields had done, and Michael Kelly after him would do. Edward often represented the Company at investigations and on committees. In 1868 he applied to Cottingham Local Government Board for them to provide two lamps outside of the Cemetery which they agreed to. This would have been the first street lighting on what was to become Princes Avenue.

He was less successful in 1873 when he asked them to repair the road outside the cemetery.

In 1869 he attended the Local Burial Board Committee and spoke, mentioning that new burial ground of the Corporation ( Old Western Cemetery) was rapidly filling up. The same year he had to explain that it was Company policy to give visiting clergymen a surplice at the office and not to give them a surplice at the graveside as one irate clergyman demanded. The Burial Board sided with Edward.

An important meeting

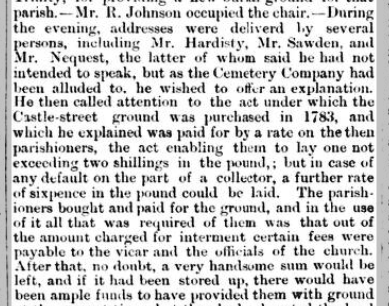

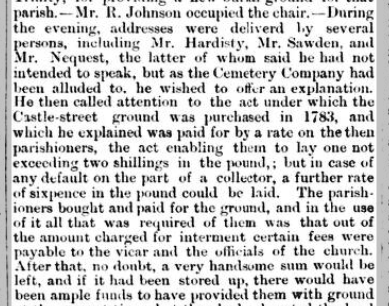

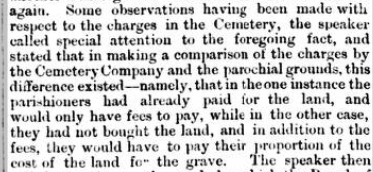

A more important meeting that Edward attended took place before this appointment as superintendent. On the 21st April 1860 the Hull Advertiser recorded his intervention into a meeting of the South Myton Guardian Society.

In the meeting, which appeared to have been called as to whether the parishioners of Holy Trinity should pay for a new burial ground, Edward was forthright. The snippets below, taken from a very long article, show that Edward was a bright, eloquent speaker who was passionate about the Cemetery.

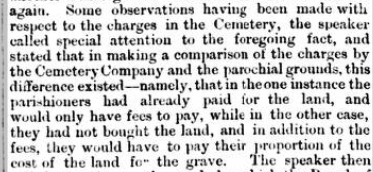

Still later, in defending the Hull General Cemetery’s charges,

Needless to say that the parishioners voted against having a rate set against them for the purchase of a burial ground. The result of this was that Castle Street continued to be used for burial for a further year until Sophia Broadley donated the land to lay out Division Road cemetery in 1862.

1871 and after

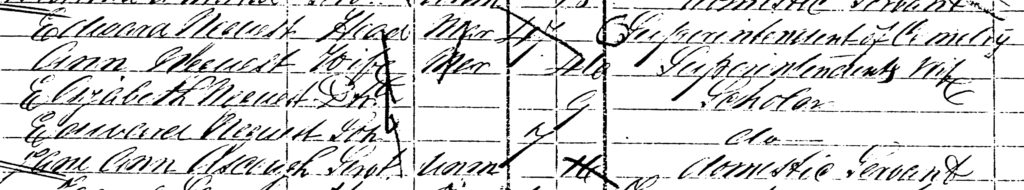

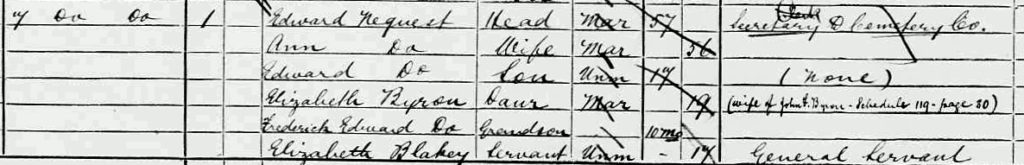

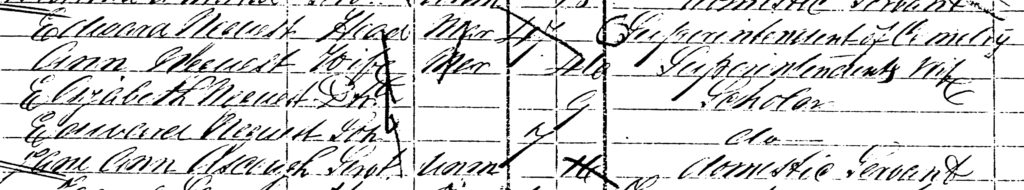

By 1871 his family had increased and living in the lodge must have become a bit tiresome.

As we know, three years later he requested that he be allowed to move from the lodge. Anniversary January 1874 This request was accepted by the Board and he moved out to a larger house. This was at 7, Zoological Terrace, situated on the corner of Norwood street and in between the Swedenborgian Church on one side and St Jude’s on the other corner of Norwood Street.

It is the building with the group of men outside of it on the pavement in this image. Here’s another image and it is the house with the steeple behind it.

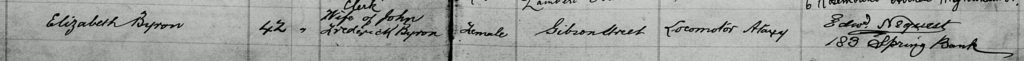

Edward continued to live at this address until his death in the 20th century. By the time of the 1881 census there had been no new additions to the family but as you can see below Elizabeth had married.

A terrible decade

She had married John Frederick Byron and had borne him a son, Frederick Edward the following year. Her husband was still living with his parents at 47, Stanley Street and he lists himself as a ‘foreman of wine and spirits warehouse’.

In the 1880s his daughter, now Elizabeth Byron, lost three children. Ann on the 22nd of October 1885. She was 5 days old. The cause of death was put as premature birth. The following year, in October 1886, Ellen died at the age of 12 days old. Her cause of death was listed as disease of the spine. And in the February of 1889 another daughter, Lillie, died at the age of four from croup.

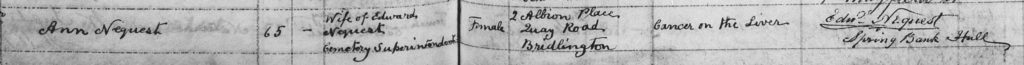

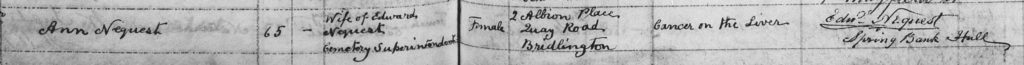

Culminating a terrible decade for Edward in the September of 1889 he lost his wife Ann. She died of cancer of the liver. Her death took place at 2, Albion Place, Quay Road, Bridlington. Cancer is rarely a sudden death and I surmise that Ann was away from home, probably with Edward, as a holiday / leave taking for both of them.

Going through the motions

It’s fair to say that the loss of his wife was a disaster for Edward. I would suppose that he no longer wanted to be associated with death for it now held painful memories for him. Sadly, worse was to come.

In the meantime, in the September of 1891, he offered his resignation from his post as Superintendent and Secretary for the Hull General Cemetery.

Its arrival is recorded in the Company minute books,

‘Read a letter that from Mr Nequest tendering his resignation of the office of secretary as and from 30 instance. Resolved that such a resignation be accepted. Read a letter from a Mr Kelly of Granville Street, Hull, for the office of secretary and superintendent rendered vacant by the resignation of Mr Nequest and after considering the same and it appearing that Mr Kelly was suitable person to fill the office it was resolved that Mr M Kelly be and he is hereby appointed secretary and superintendent on the terms named in his application.’

His daughter

Edward’s daughter by now had a family of three children. Frederick Edward now aged 10, Charles aged 8 and Gertie, born that year. Her husband, John Frederick, now listed himself as a dock labourer, so a definite coming down in the world for the family. They lived at Ebenezer Place, Raywell Street which was off Charles Street.

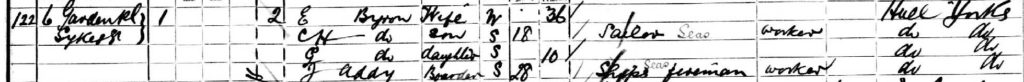

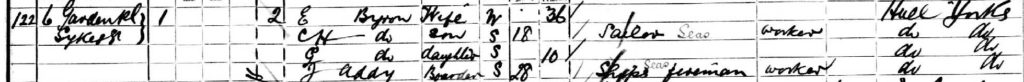

By the 1901 census John Frederick is nowhere to be seen and Elizabeth is listed as a widow. Indeed this is strange record for all the inhabitants are simply designated with initials.

The truth of the matter is that John Frederick had absconded to the United States where he proceeded to make a new life for himself and scant regard for his past life.

His mother had died in 1883 and his father died in 1894. By 1895 he had emigrated. two years later he committed bigamy by marrying Ruth Newman on the 15th September 1897 in Salt Lake City. I say committed bigamy but Salt lake City was and is the home of the Mormon religion and polygamy is accepted and recognised there. Did John F Byron become a Mormon? We have no way of knowing. Suffice to say that he had six more sons and five more daughters whilst in the USA so we can say he embraced his second wife if not the religion. He died in 1918 in Idaho.

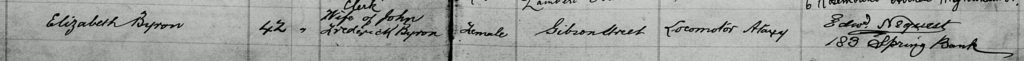

Her illness

We have no idea why he absconded. It could well have been that his wife Elizabeth was ill. She eventually died from locomotor ataxia. This disease was and is extremely problematic and embarrassing for sufferers. Predominantly it is a disease of the spine. It manifests itself in locomotion issues such as jerky walking and disorientated movements which give the appearance of being drunk. Sufferers need to constantly check where there are limbs are. It is often a symptom of Tabes Dorsalis which itself is often a symptom of tertiary syphilis.

Elizabeth died in 1903. She is buried in grave number 14765, the bottom burial plot in the image shown earlier. You many note that the other grave plots are classed as B whilst Elizabeth’s is D. She is the sole occupant of that grave plot. I’m sure, like me, you can hypothesise about why this occurred but it is only guesswork and perhaps we should leave this tragedy untroubled.

1911 and beyond

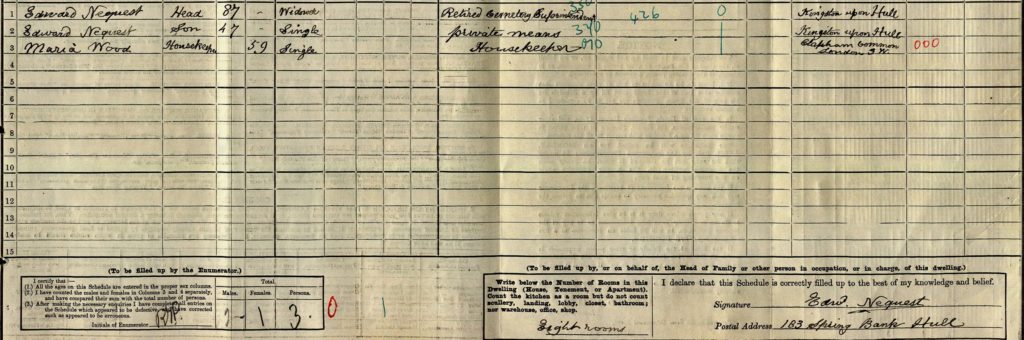

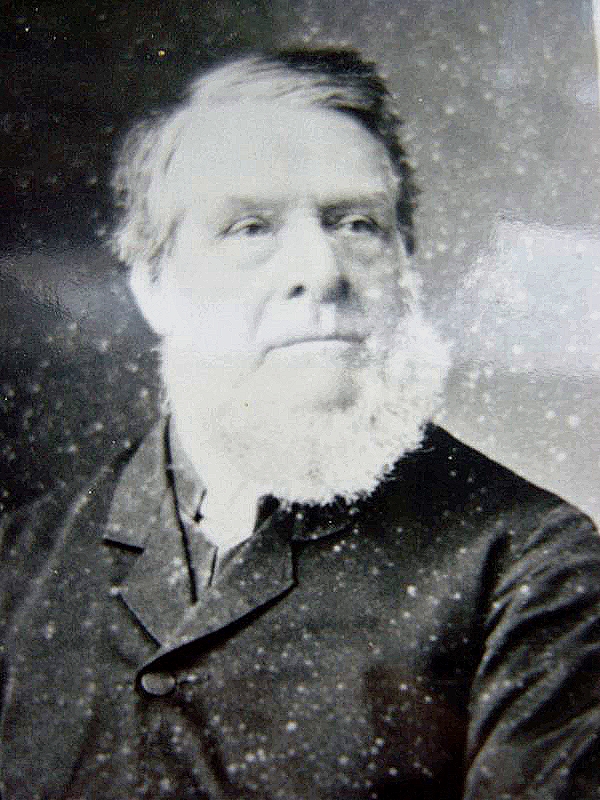

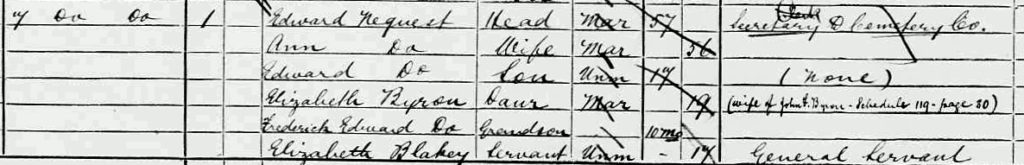

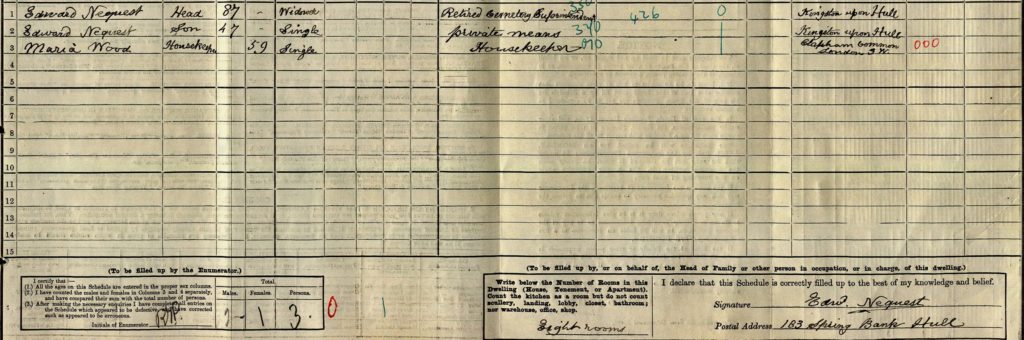

The 1911 census shows Edward living in his home with his son Edward and a housekeeper. The house was spacious consisting of eight rooms and both the Edwards appear to be living a comfortable life.

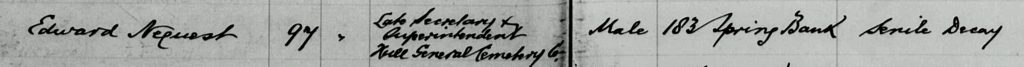

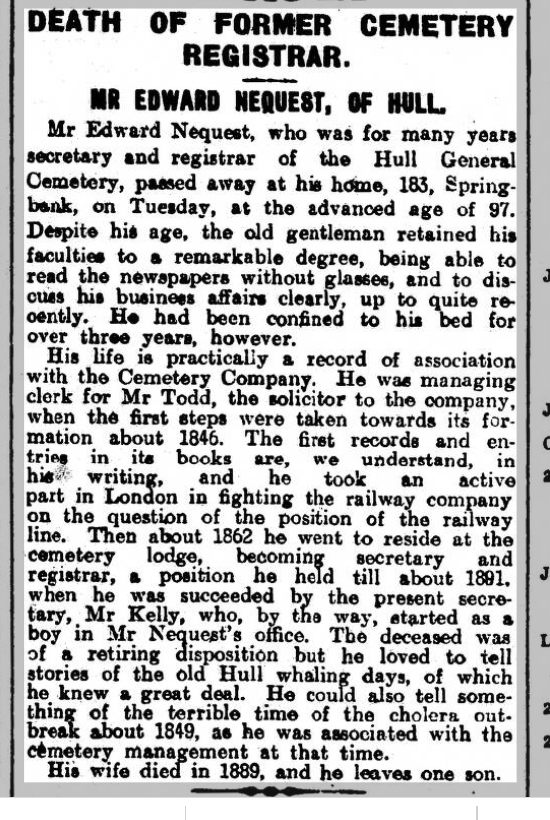

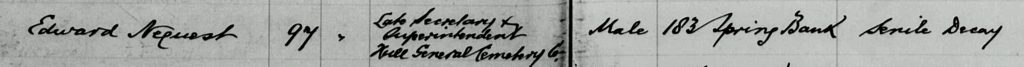

The elder Edward died on the 3rd July 1920 at the age of 97.

His son then married! At the age of 56!! Once again we can wonder at this turn of events. Did the younger Edward love someone whom his father disapproved? We shall never know. And once again tragedy stalks this family. The younger Edward survived his father by less than five months, dying in the December of the same year.

He left a gross estate of £3,301 and personal wealth of £731 to his new bride Mary Elizabeth (nee Young) who continued to live in 183 Spring Bank. On February 2nd 1949, Mary Elizabeth Nequest died. She was cremated and her ashes were buried alongside her husband and her in-laws in grave number 14363. With her death this line of the family ended.

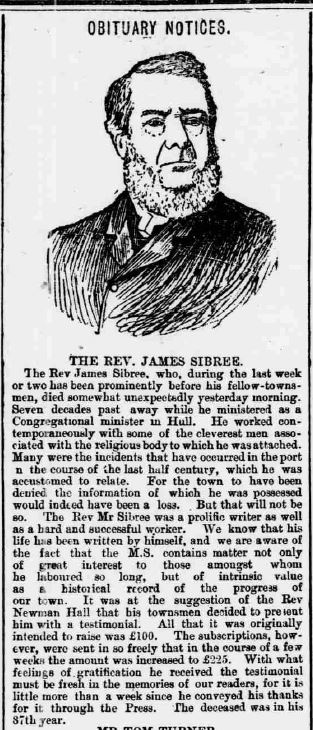

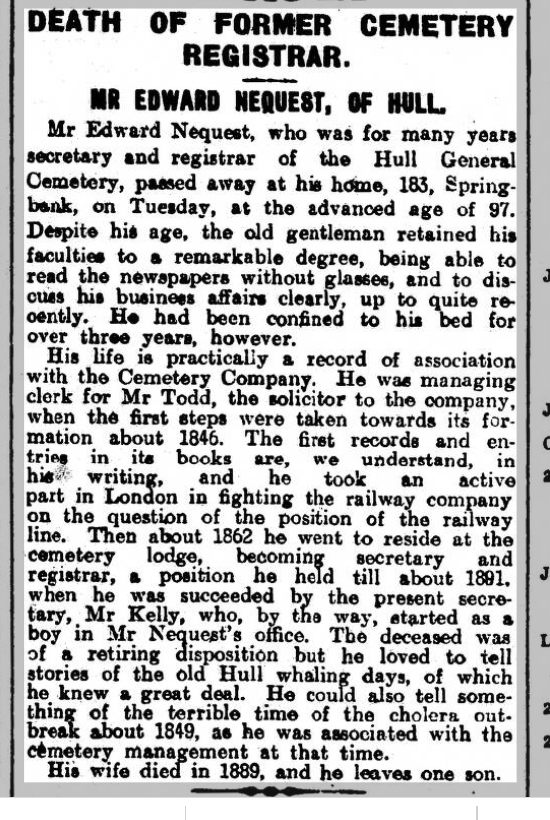

Obituary

Finally let us leave with the obituary that the Hull Daily Mail saw fit to print about Edward.

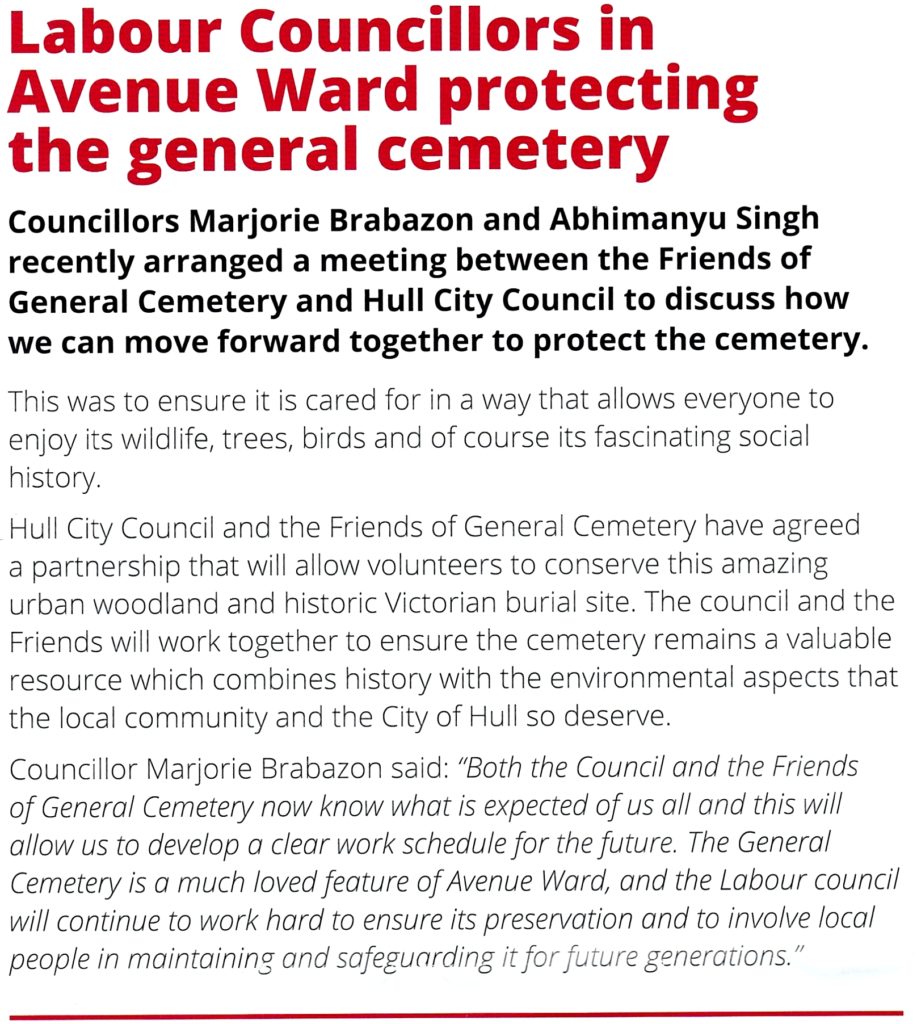

Pete Lowden is a member of the Friends of Hull General Cemetery committee which is committed to reclaiming the cemetery and returning it back to a community resource.