The Coming of the Railway

This month’s anniversary is related to the railway that once ran past its gates.

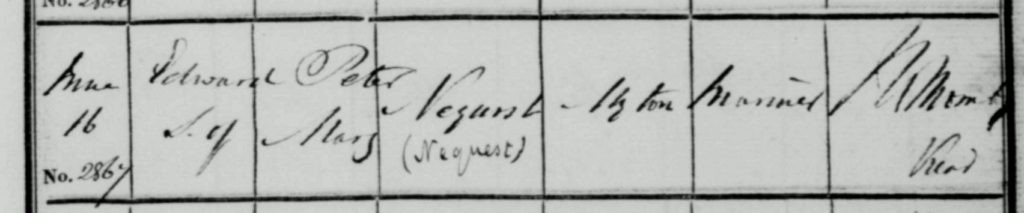

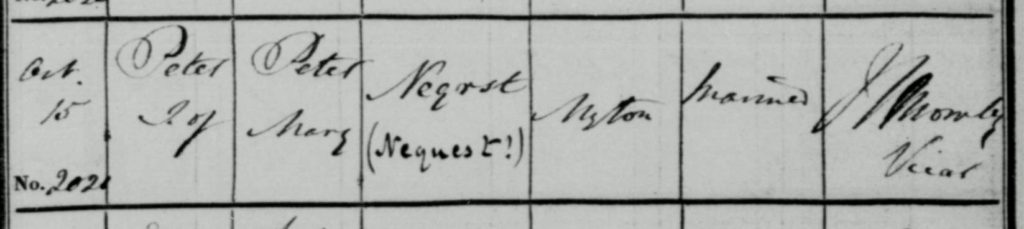

On the 2nd September 1852 the Board received an engineer’s report. This engineer was employed by the York and Midland railway Company. This report detailed a new layout for the proposed branch line to the Victoria Dock. It was the culmination of a campaign waged by the Company to get the railway company to change its mind. And it was a success. Let’s go back a bit and see how this situation came about.

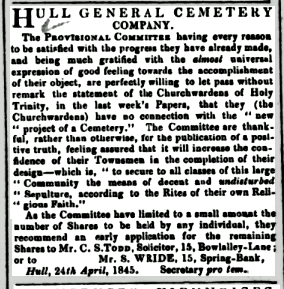

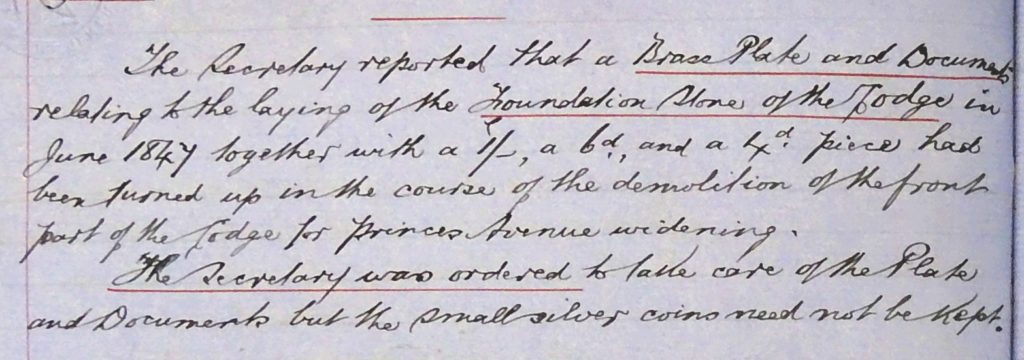

Back in December 1851 the Board received an unexpected and definitely unwanted Christmas present. C.S Todd, the secretary reported that,

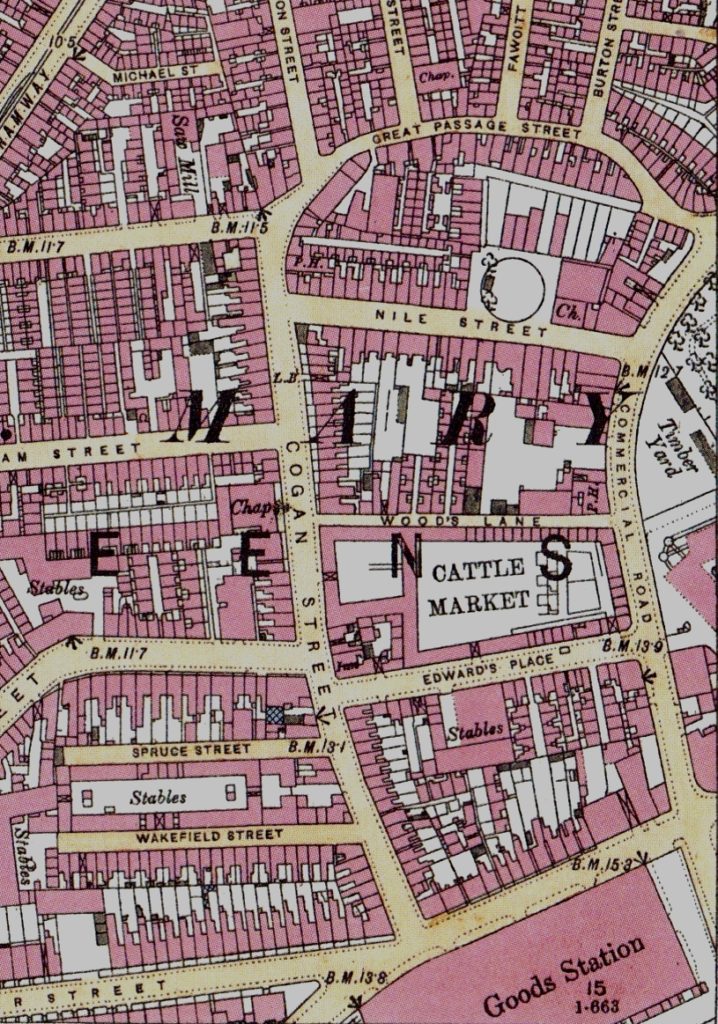

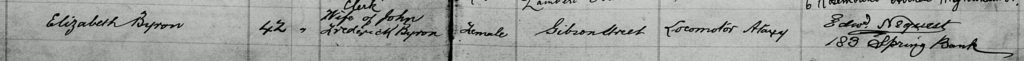

‘plans and sections of the proposed Victoria Dock Railway had been lodged with the clerk of the peace for the borough of Kingston upon Hull on Saturday evening and that the proposed railway was projected to pass between the north west corner of the late waterworks and the gates of the Cemetery at a distance of comparatively a few feet and requested instructions as to the course under such circumstances.’

What to do?

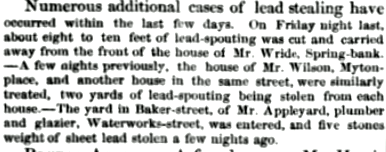

Obviously this development caused consternation with the Board. They knew that a branch rail line was in development but they had no idea it would impinge upon the cemetery. That it would run a ‘few feet’ from the entrance would be disastrous for the cemetery. The effect it would have upon the Lodge was also something that had to be taken into consideration. The Board knew it had to do something quickly.

‘It was resolved that a deputation consisting of the chairman, Mr Irving, and Mr Todd do wait upon the Directors of the York and North Midland Railway Company upon the subject of the injury to the cemetery in consequence of the above railway and that in the meantime the solicitor do see the plans lodged and get all the requisite information upon the subject.’

The meetings

The meeting with the Railway Company was soon forthcoming. The meeting took place on the 14th January 1852. To say it wasn’t a success would be putting it mildly. The Railway Company saw no reason to change their plans. If it caused the Cemetery Company problems , well that was no concern of theirs.

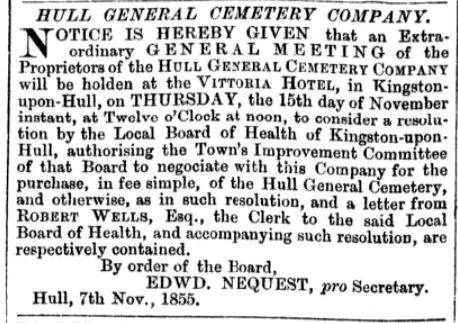

The Company employed their own engineer, Mr Clarke, to draw up alternative plans for the route of the railway line. The Board also thought that an extraordinary meeting of the shareholders should be called to inform the proprietor’s of this situation.

This meeting took place on the 20th February.

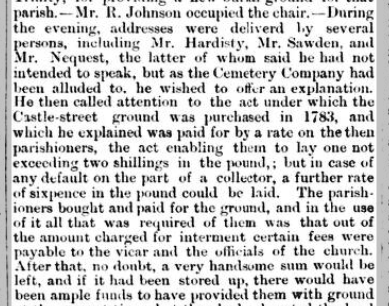

‘The chairman opened the proceedings by stating succinctly to the meeting what had already been done by the directors respecting the proposed crossing of the railway Company immediately in front of the cemetery’.

He then called upon the secretary to read out the correspondence between the Railway Company and themselves. Sadly none of this survives but the Secretary, in the minute book, does state,

‘that he had received from the directors of the Railway co., a letter by no means satisfactory inasmuch as it bound the company to no fixed mode of arrangement’.

Oh, the wealth of meaning behind his clipped legal words.

The feeling of the meeting was pretty high at this point and the proprietors made their views quite clearly to the Board and the meeting,

‘fully authorised and empowered (the Board) to take such steps for the protection of the Company’s interests in the matter of the railway crossing as they may be advised and deem right and that if necessary they be authorised to proceed to parliament for the purpose of attaining that object.’

Parliament

This was the nuclear option and the Railway Company probably did not see it coming. The issue was raised with the standing committee of transport and by May a resolution was forthcoming. The Railway Company accepted the plans as put forward by the Cemetery Company,

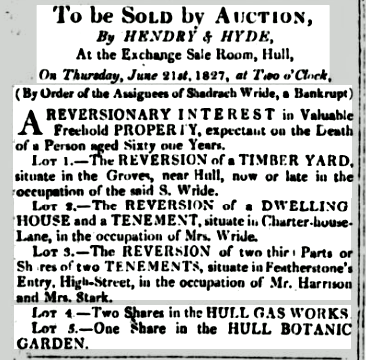

‘and that the railway Company had agreed to pay this company £2500 on condition that certain suggested alterations should be made at the entrance of the cemetery.’

So, a victory for the Cemetery Company. Well, not quite. Firstly the railway line was still to run quite close to the front of the Cemetery. Secondly, what were these ‘alterations’ mentioned?

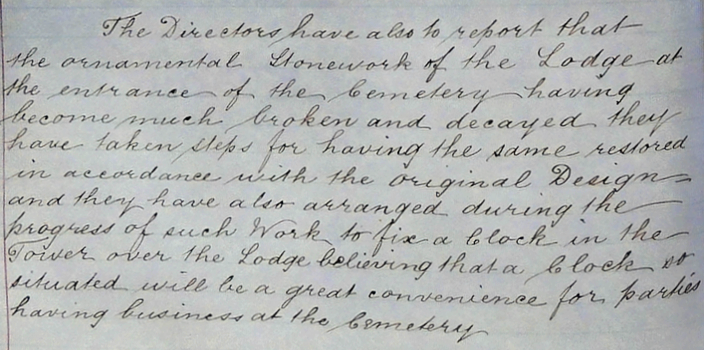

Getting the builders in

An insight into these was noted in July. The minute books state that ‘extra gate piers’ were needed at the front of the Cemetery. Where and how they would fit into the original scheme is difficult for us now to visualise. The Board empowered John Shields, the superintendent, to,

‘be authorised to purchase the necessary stone requisite for the extra gate piers and also obtain an estimate of the difference of expense to the company between our having gates across the whole of the new entrance or only palisading with a dwarf wall for two openings, both in the present and projected entrance and in the event of the latter plan being adopted then the cost of removing from the present to the new entrance two sets of the gates now at the former and that in the meantime the new walk required for a cab stand to be laid out, planted and completed forthwith.’

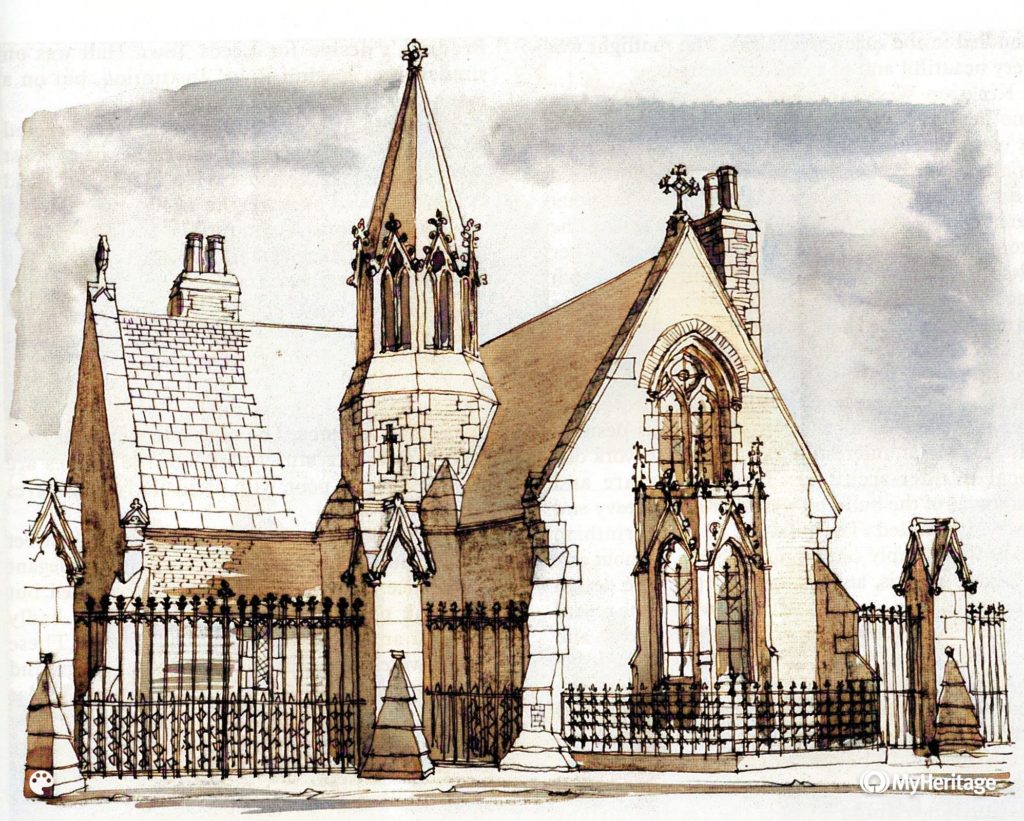

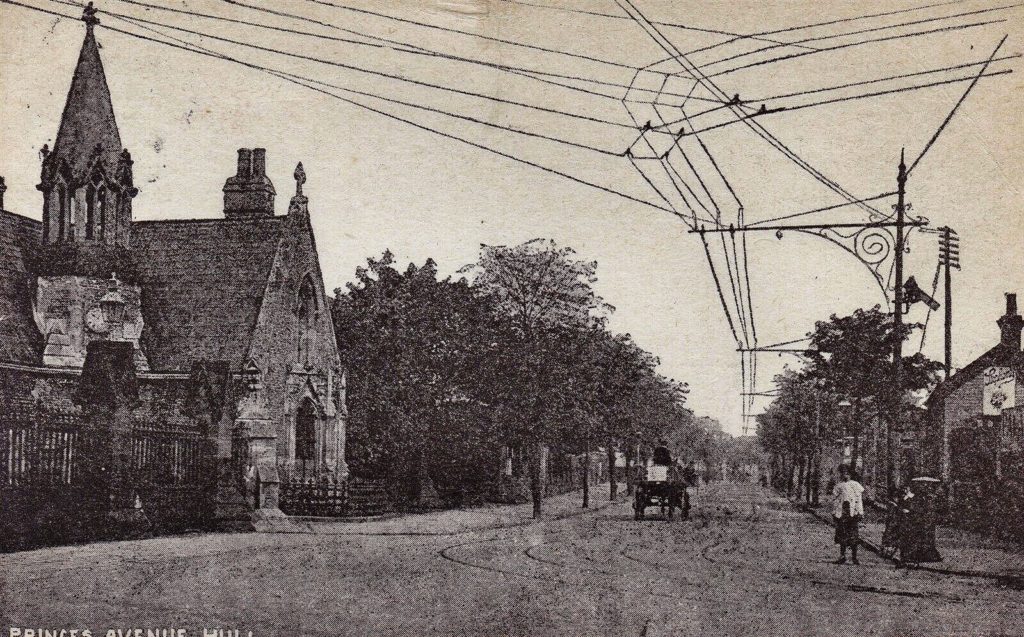

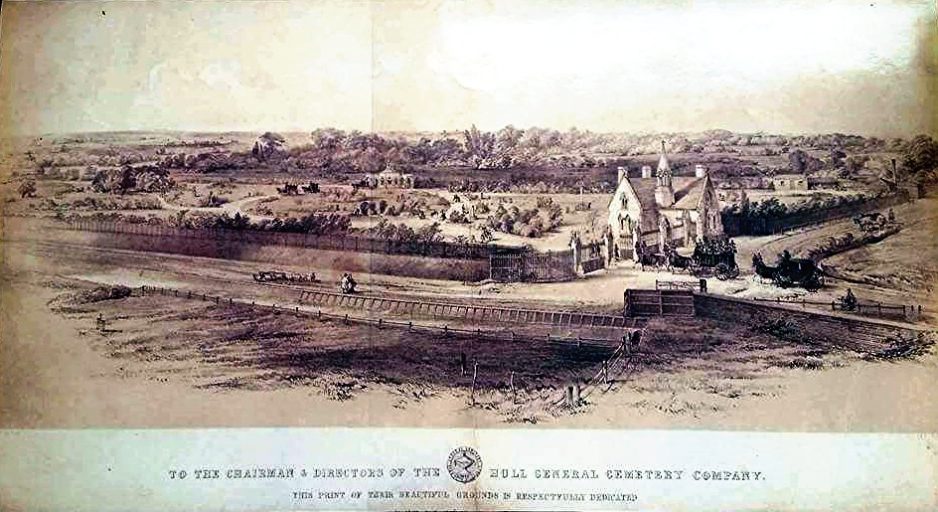

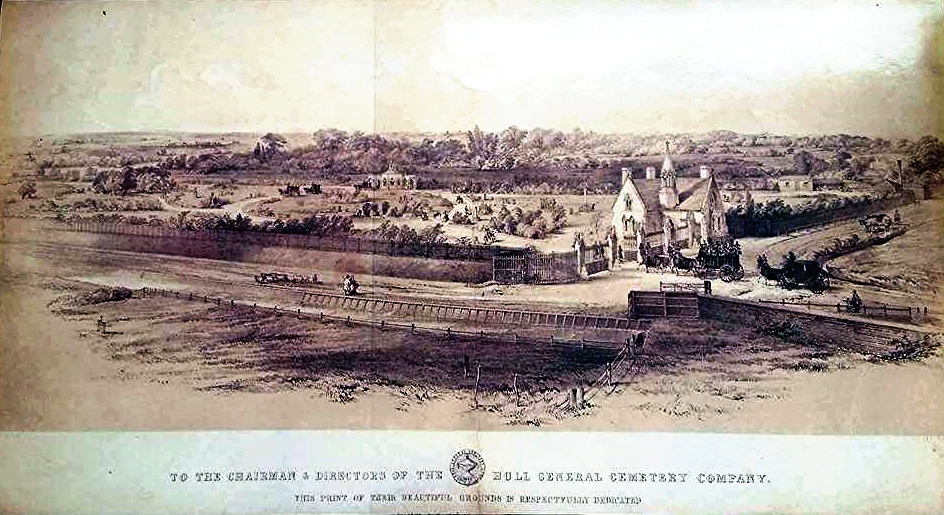

So, these were the alterations that needed to be carried out. As I mentioned visualising the changes is difficult as the only image we have before the railway was laid out is from Bevan’s lithograph which is an artist’s impression.

The lithograph shows both the lodge and the chapel built with gates. This is wrong as none of those buildings were built at the time of the lithograph being printed. There would have been some gates at the entrance but what they were like is open to question. In other words we are quite in the dark about these ‘alterations’. Suffice to say that they took place.

One cottage or two?

On the 26th August, a visit took place from Mr Carberry. This was the engineer from the Railway Company. He fully approved of all what the Cemetery Company had done. But there was a sting in his tail for he went on to show the detailed plans he had brought with him.

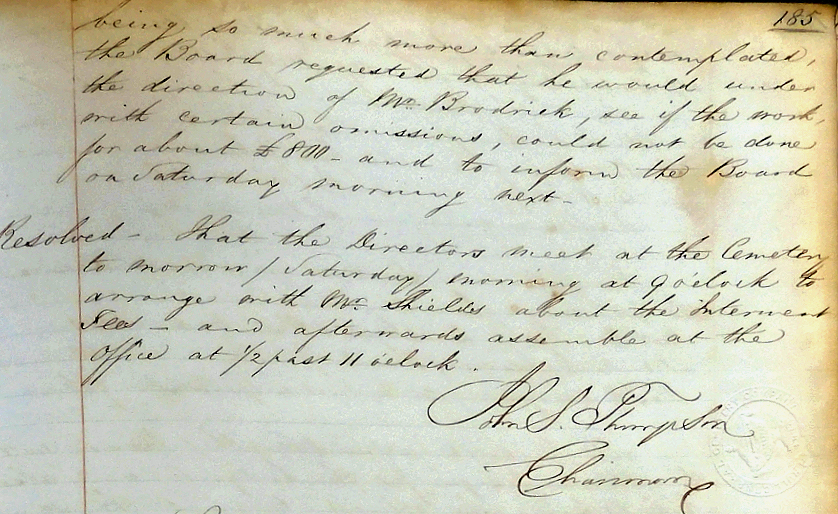

‘Mr Carbery then laid before the Board the plan and sections for the Gatekeeper’s house, as proposed to be erected by the Railway Company, and the same having been examined by the Board, and it appearing to be the intention of the Railway Company to erect such house in front of the entrance lodge of the Cemetery.

It was determined to make an offer to the Railway Company to build them a gatekeeper’s house on the ground of the Cemetery and corresponding in style and architecture with the Cemetery lodge, on receiving from the railway Company £100 the amount intended to be expended by them, the additional expense to be borne by this company and that in the event of such an offer being accepted another house should be built on the other side of the lodge in uniformity with the gatekeeper’s house and Mr Carbery stated that he would lay such an offer before the Railway Directors and recommend that the same should be carried out as proposed.’

Horrified

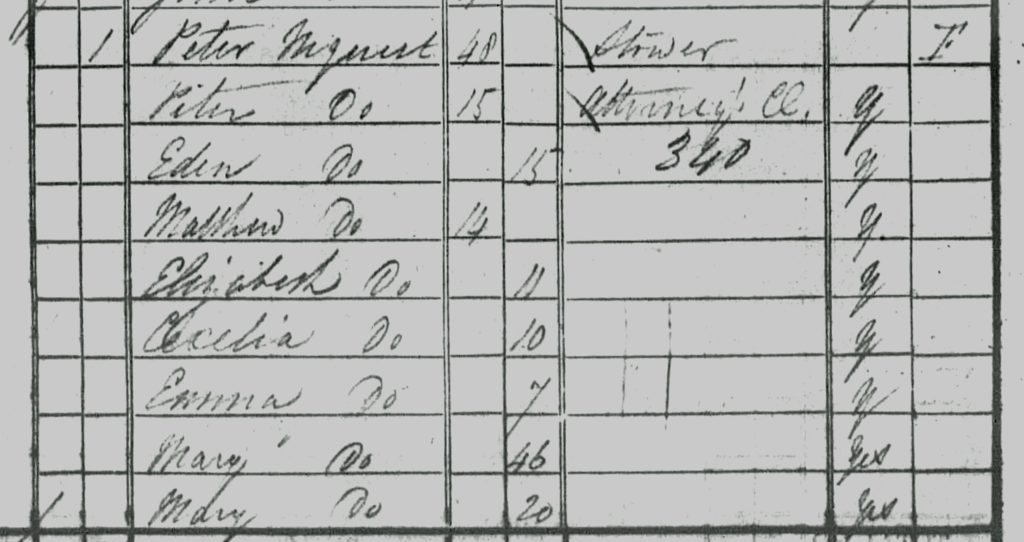

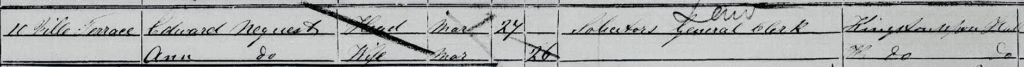

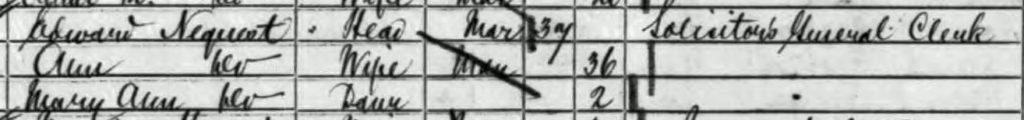

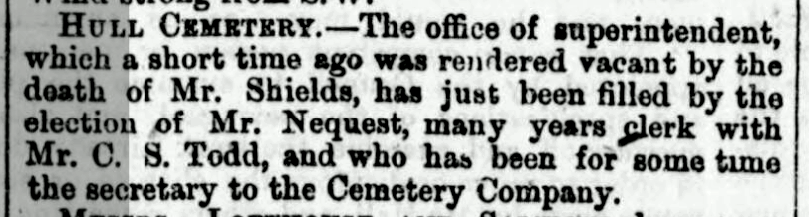

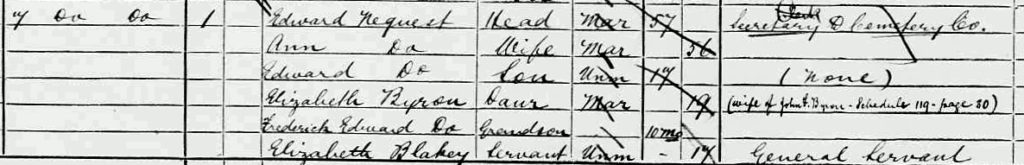

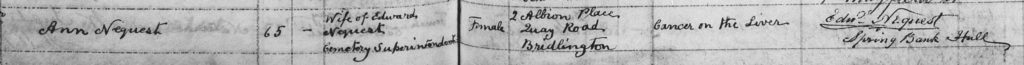

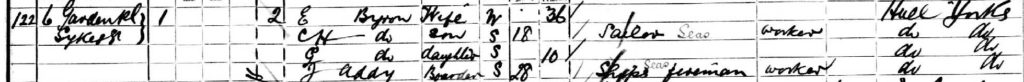

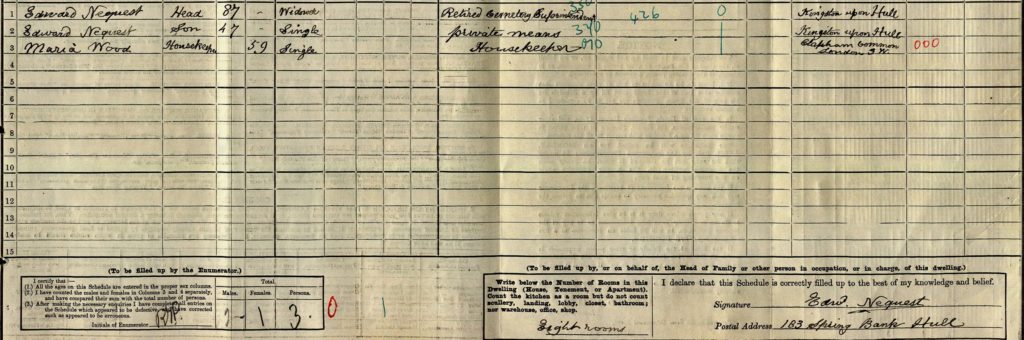

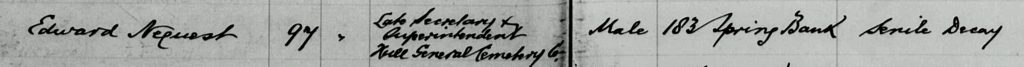

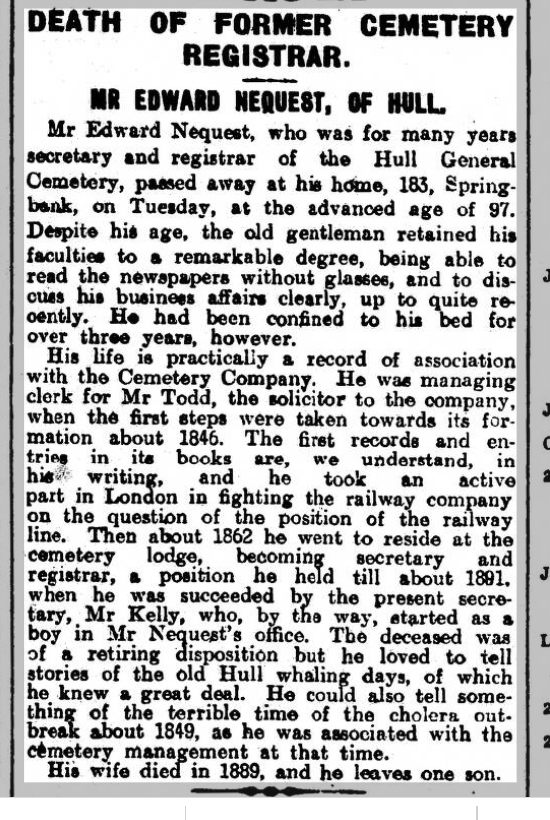

The Cemetery Board must have been horrified by the idea that a workmen’s hut should be placed in front of the Lodge. But they knew that they could not resist this insult. That is, unless they upped the ante. This they did by saying that they would build the gatekeeper a house on their land to the west of the Lodge, in the style of the Lodge. This was agreeable to the Railway Company and the gatekeeper of the level crossing for Botanic Gardens Station lived there until its demolition in 1907. That the Cemetery Company then felt the need to add ‘balance’ to their frontage and erect another cottage to the east of the Lodge was simply just showing off. It was used to house the foreman of the Cemetery staff which at this time was a man called George Ingleby. He remained there until the 1890s.

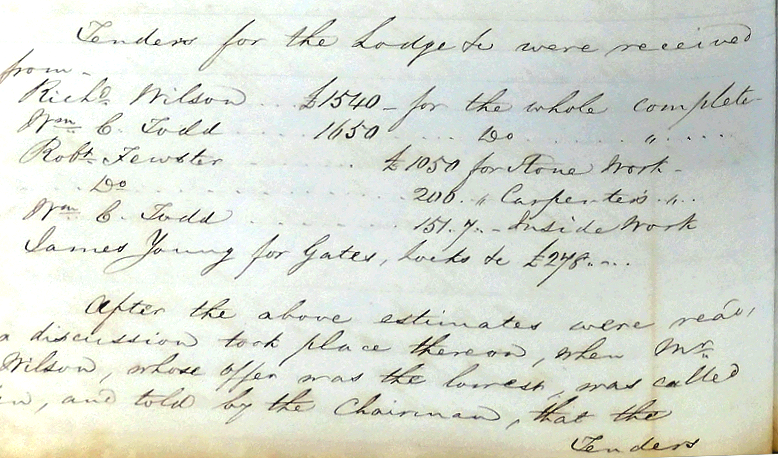

Not top of the range

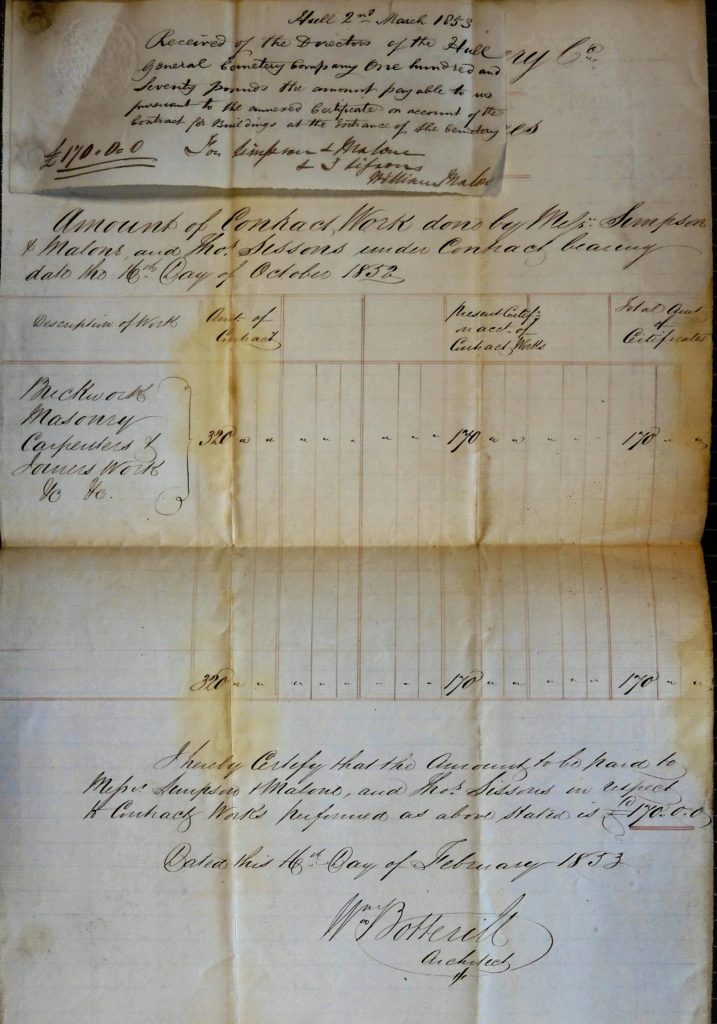

These cottages were not built to the standard of the Lodge. Simpson and Malone, quality builders and stonemasons, wee employed to construct them. As the bill tendered for payment indicates, the cost for building both cottages was £170 each. The lodge cost much more than that. Still one had to keep up appearances. The final bill for the cottages came to £320 when other aspects were taken into account. The Company probably thought it had done well getting 320 knocked off the price.

And so we come to that date in September 1852. The anniversary of the coming of the railway to the Cemetery. At the meeting,

‘A letter was then read from Mr Gray, the secretary of the York and North Midland Railway Company, accepting the offer made to Mr Carbery as to building the gatekeeper’s house on the Cemetery grounds provided his company would give to the Railway Co. a lease of the house for 21 years and after the expiration of that period agree not to terminate the tenancy unless upon giving 6 months’ notice and repaying the said sum of £100 and the matter having been discussed it was resolved that this Board do approve of such an arrangement and that the secretary be requested to communicate with the Railway co.’s secretary in order to carry out the same.’

And there the matter was resolved.

The final cost

However, was it worth it? Was the proximity of the railway line to the front of the Cemetery that important? We are not in a position to judge whether the moving of the track bed by a few feet was so vital to the interests of the Cemetery. Obviously the Company thought it was. But was it worth it? Ah, that’s good question, especially knowing how things turned out for the Cemetery.

Firstly we have no idea what the cost was for the erection of the extra gate piers but it was a cost the Company had no need to indulge in at that time. Secondly, we do know how much the erection of the cottages cost and that was £320. Yes, they were a fixed asset and they received rent from them but it was a cost that was unnecessary. Thirdly, parliamentary time does not come cheap and the cost of that was £850 5s 1d. This is a considerable sum. The cost of buying the entire site for the Cemetery was only just over £5000. And then we have the cost of the new gates, ordered from Thompson and Stather for £53 10s.

So, overall a cost of northwards over £1200. The Bank of England inflation estimator reckons this sum would be worth £116,966 today. Now that’s quite a tidy sum to spend because you don’t want to have a railway track next door. Some people might say that about having a Cemetery next door. There’s no accounting for taste.

Pete Lowden is a member of the Friends of Hull General Cemetery committee which is committed to reclaiming the cemetery and returning it back to a community resource.