Peter Hodsman

Peter Hodsman. A common enough name. However in the story of Hull General Cemetery he stands alongside John Shields, Cuthbert Brodrick, John Solomon Thompson and other luminaries. Peter has left a legacy for us all. Much more than any of the others already named. For you see he was a stonemason of the cemetery.

Let me tell you a little about him.

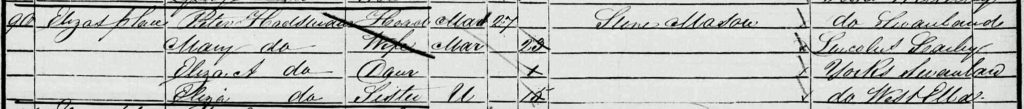

Peter was born in Swanland in the East Riding. His father, William had been born in North Ferriby in 1797, and had married Peter’s mother, Ann Watkin in January 1813.

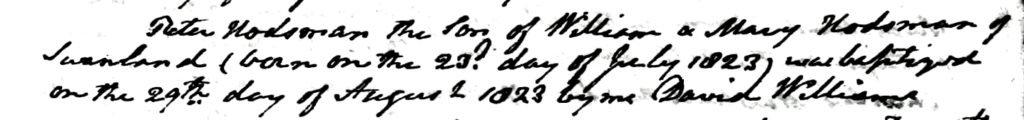

The Hodsman family were non-conformist in their religion as can be seen by Peter’s baptism record above. This may have had some bearing on Peter’s work in the future.

Peter doesn’t feature in the 1841 census. Nor does his father. This may well be due to an enumerator error. The possibility of recording the name as Hodgson cannot be ruled out. Many such instances of this occur in this particular census.

Marriage

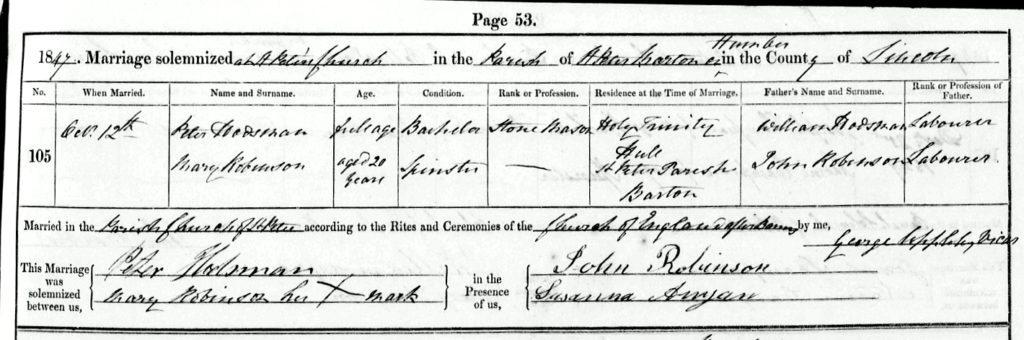

The next time we meet Peter is at his wedding. This took place in the ancient church of St Peter’s, in Barton on Humber. He married Mary Robinson on October 12th 1847.

Much can be gleaned from this record. Firstly that Peter now lived in Hull, in Holy Trinity Ward. Secondly that his trade was now that of a stone mason. Thirdly that he was literate as evidenced by his wife’s mark. And a mystery too. Why did he marry in an Anglican church?

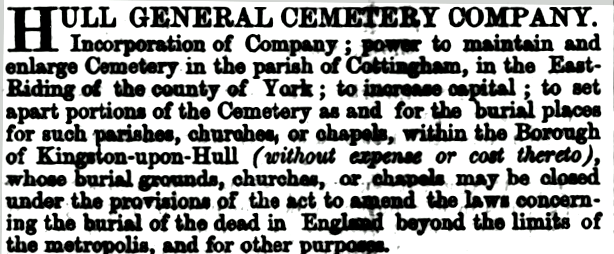

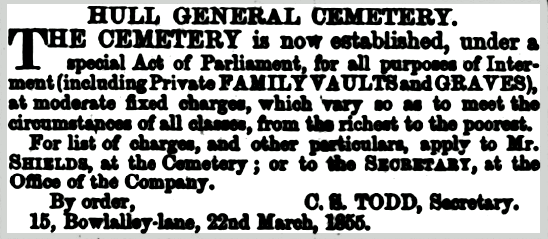

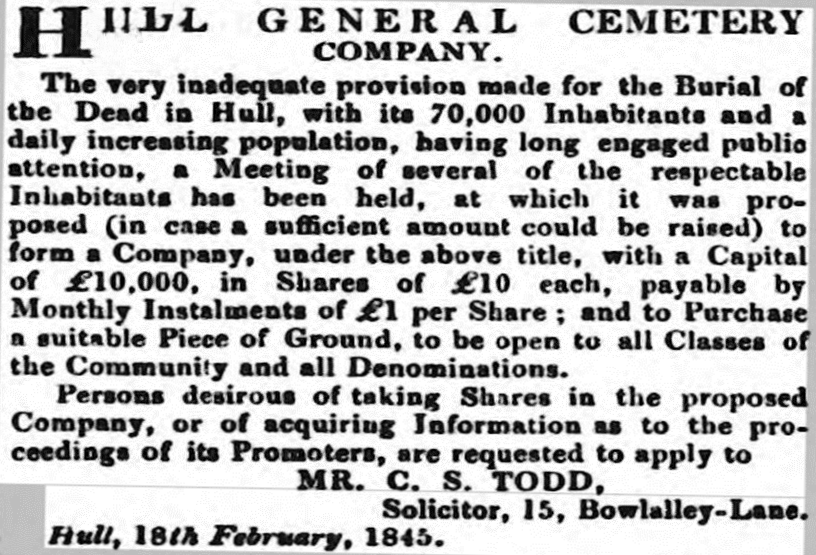

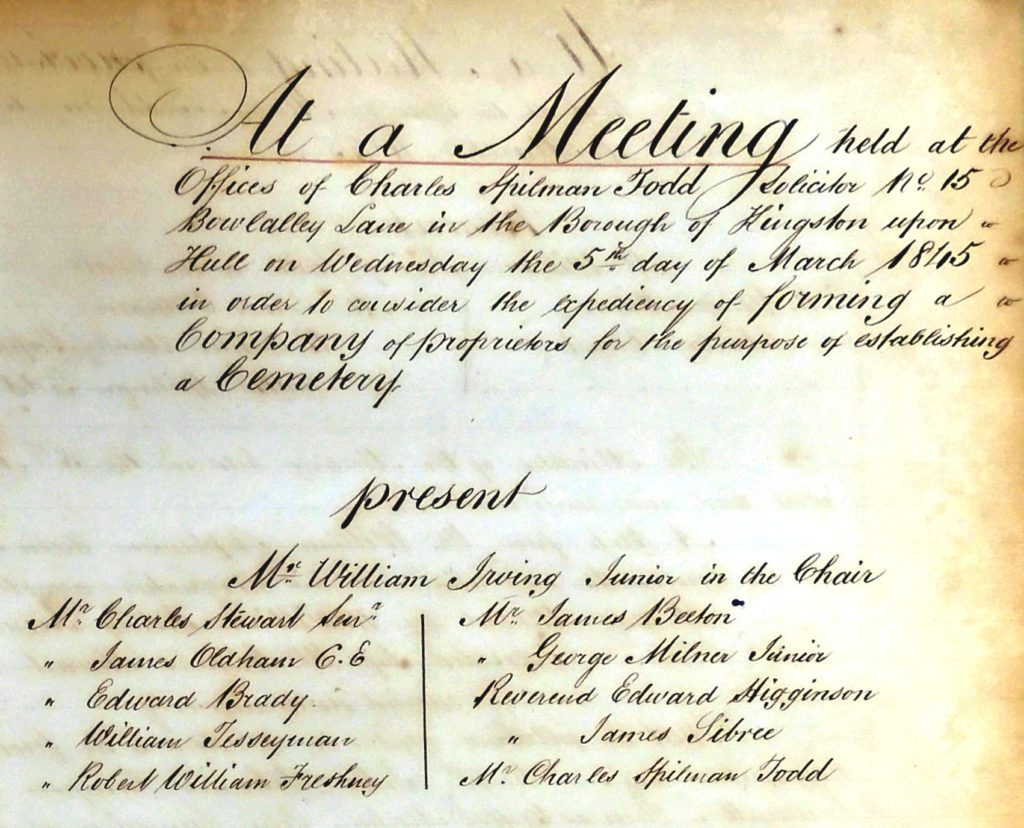

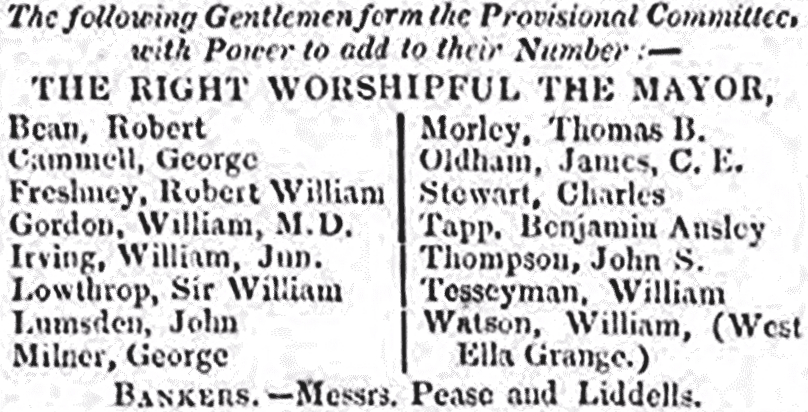

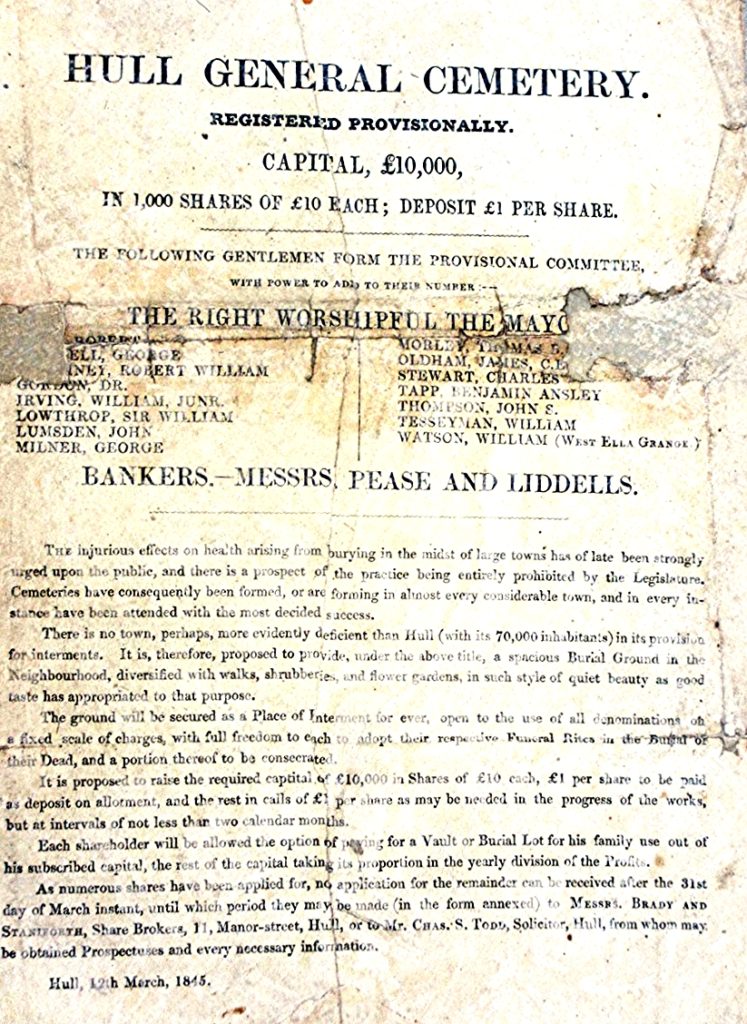

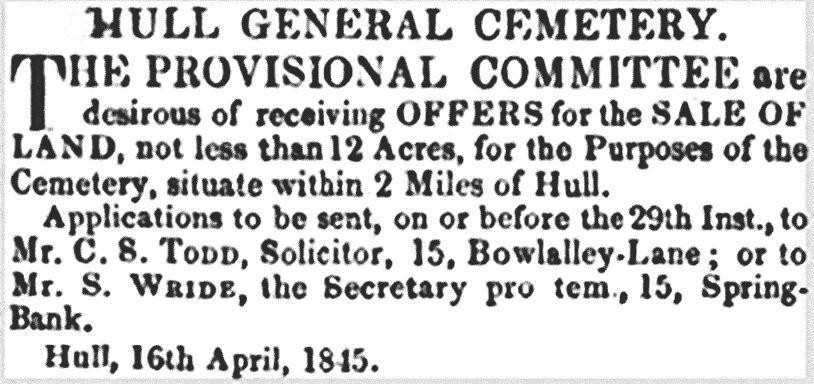

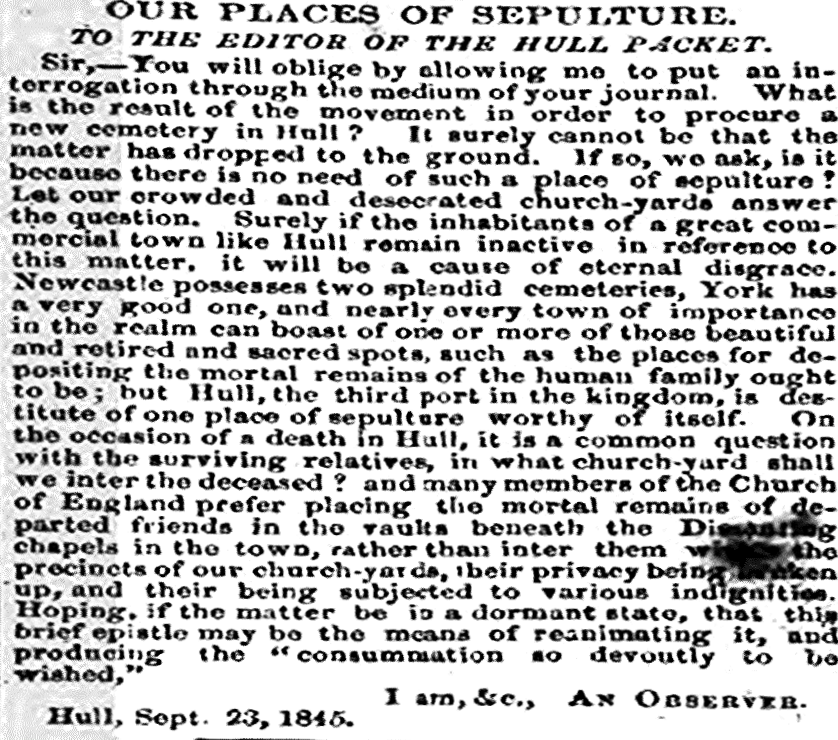

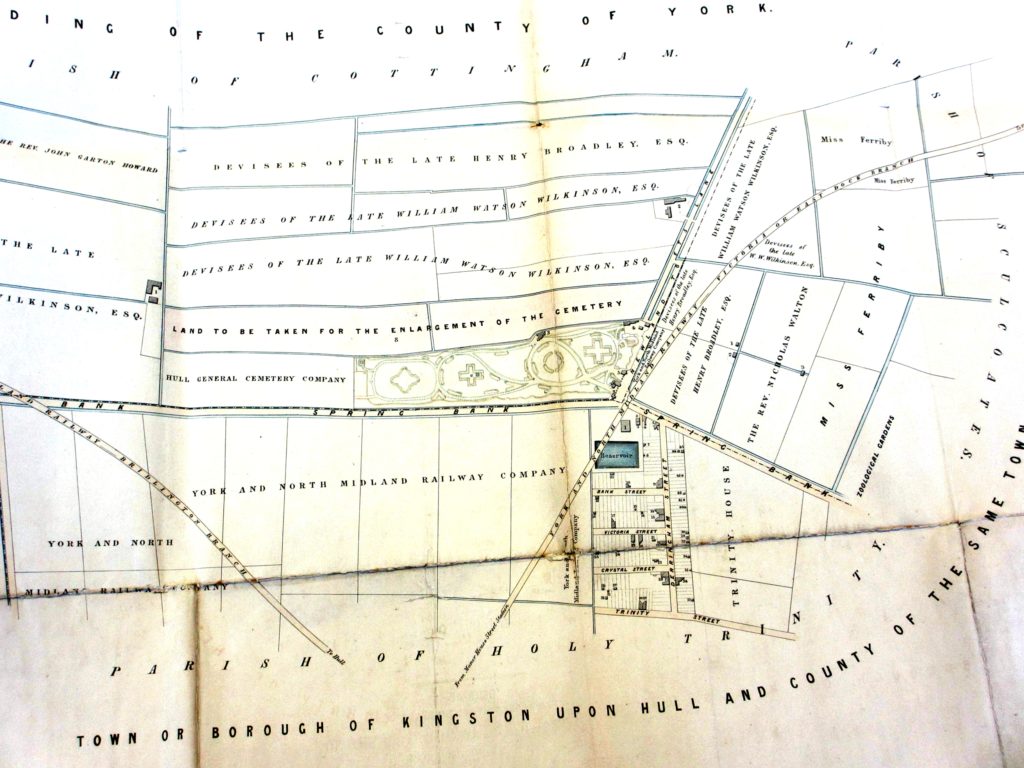

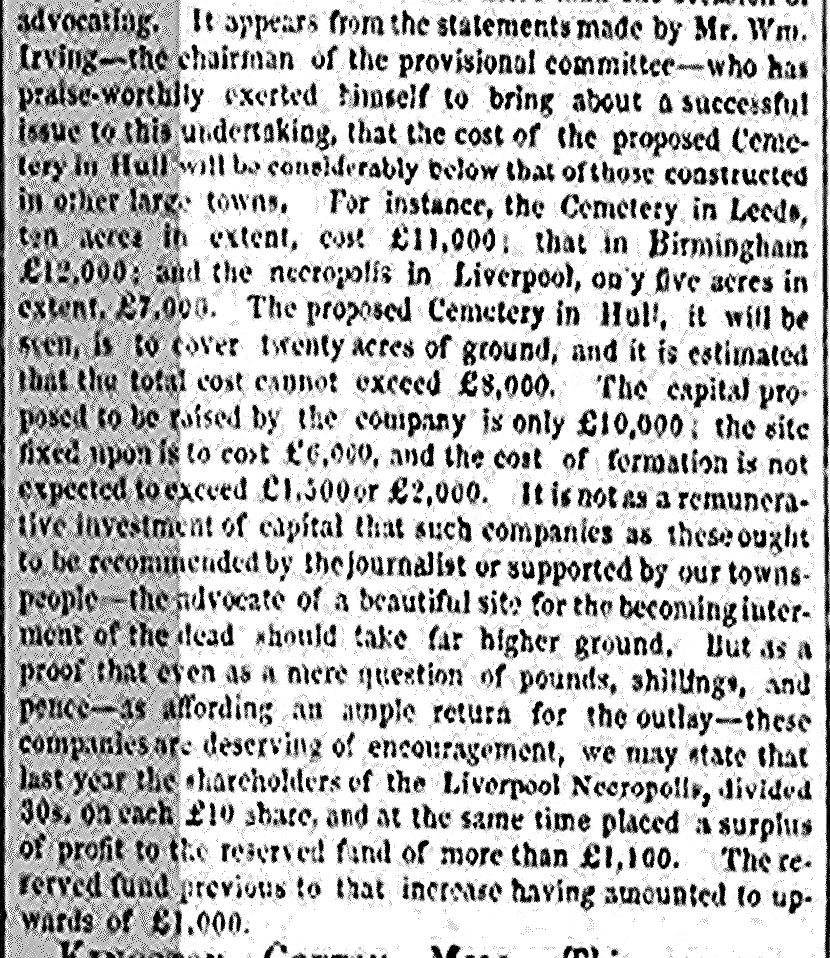

The Cemetery

As you all know, Hull General Cemetery was opened in 1847 and it would have seemed likely that this place would have been a good source of employment for a stone mason. Of course, we do not know when he began working at the cemetery. Employing the workforce was not something that was deemed important enough to record. Perhaps that’s one of the reasons I feel its important to record their existence. Let’s face it, without them the Cemetery would not have happened.

We do know that in March 1849, some 5 months before the great Cholera epidemic struck, the Directors were asking the superintendent to shed some of the workforce. At that time the Company employed just five men.

‘Four men being employed on the grounds, preparing graves, gardening and rubbing stone and one mason at the stone yard.’

It’s tempting to believe that Peter could have been this stone mason but sadly we have no evidence for this.

The Dead House

In December 1850 John Shields reported to the Board that,

‘that complaints had been made by the stonemasons engaged in the Company’s stone shed of the dangers likely to arise from the near proximity of the Dead House to such a shed and the matter having been fully considered by the Board it was ordered that the use of the present dead house be discontinued and that a new one be forthwith built on the vacant ground behind the chapel.’

Interesting as this comment may be in many ways, the reason it is cited here is that the plural use of the word stone mason is used. This shows two things at least. Firstly that, since the Cholera outbreak, business had increased dramatically for the cemetery. It also shows that the stone yard business was taking off and extra skilled workers were needed. Thus at least two stone masons were employed.

The increase in stone masons in this period

Obviously stone masons were more numerous at that time than now. Hull was going through an expansion not seen before. It’s only equal would have been the post-war boom of erecting the housing estates that encircle the city now.

During this early Victorian period many buildings were erected, some public and many private dwellings. For example in the 1839 directory of Hull only 13 stone masonry firms are listed. Three of those are the Earle’s so could count as one. By the 1861 directory this number had doubled to 27. Neither directory included the Hull General Cemetery Company’s own stone company.

The first public grave in the cemetery

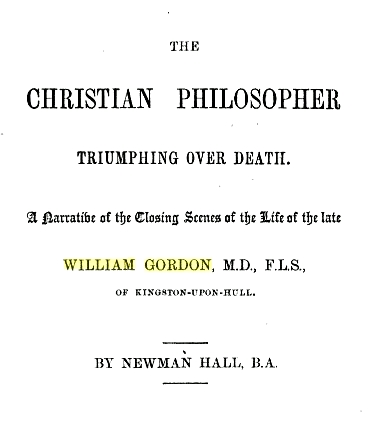

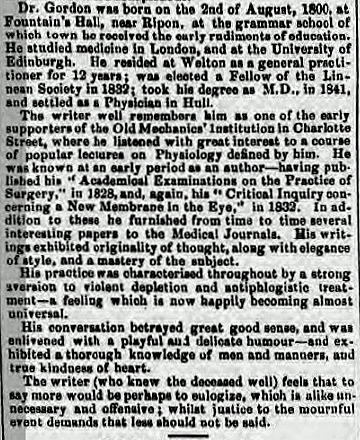

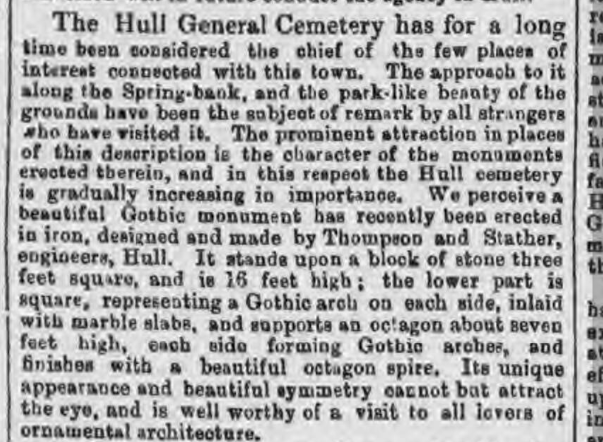

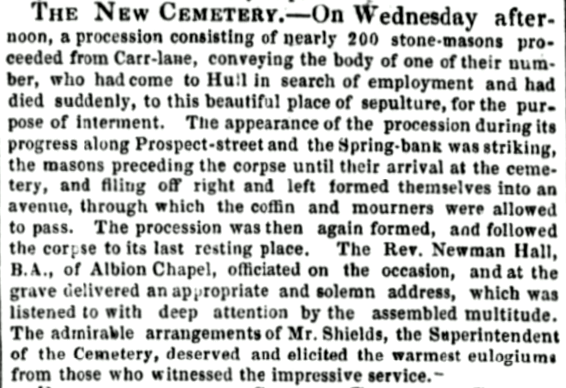

Of related interest here is the account of a funeral of a stone mason that took place in Hull General Cemetery shortly after its opening. It perhaps shows the amount of stone masons in the town at that time.

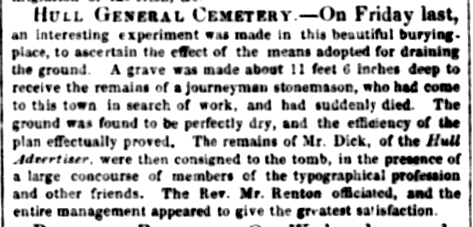

And perhaps only interesting to such people as me who love the minutiae of such doings, this grave, the very first public grave in the cemetery, was used as an experiment as the Hull Packet describes,

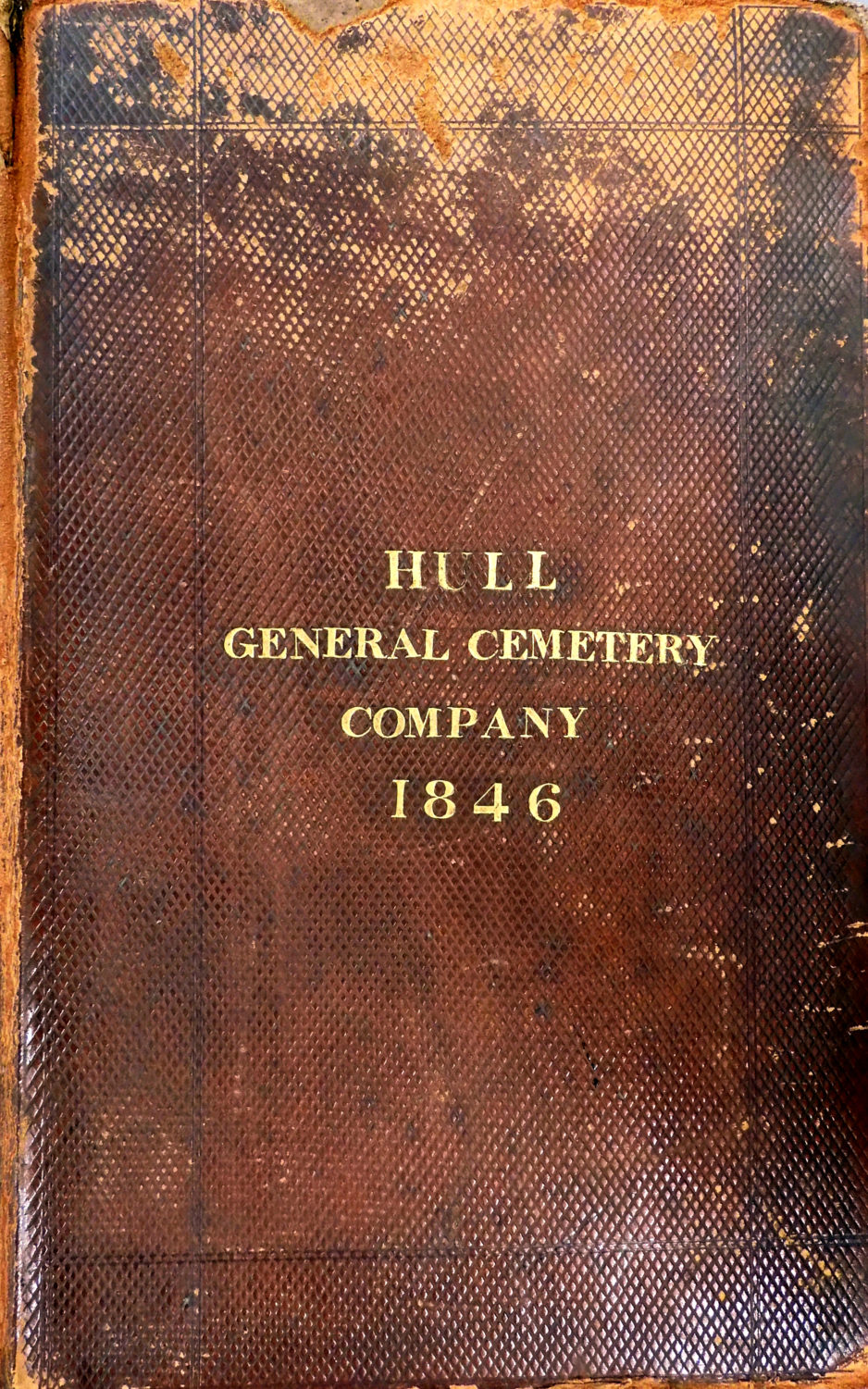

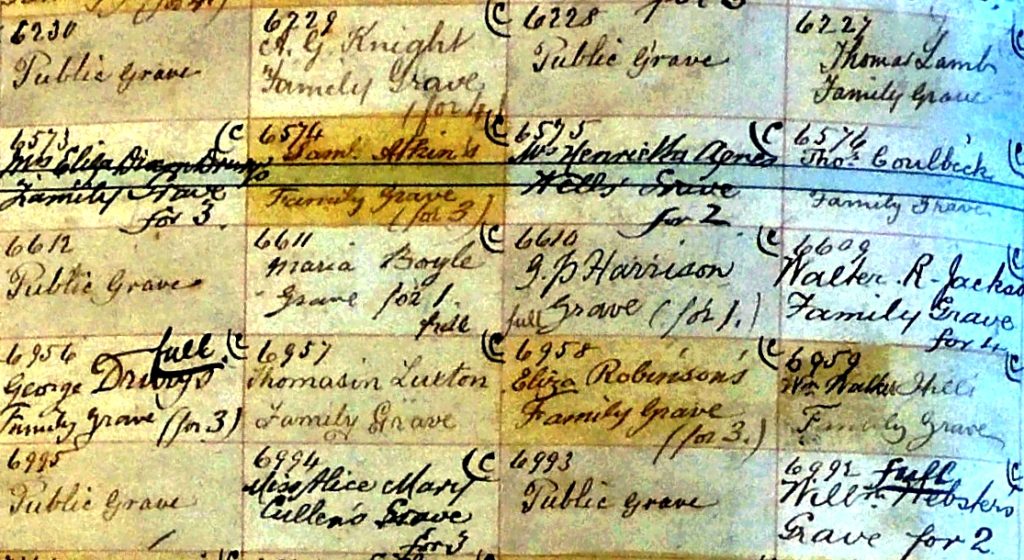

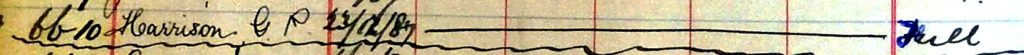

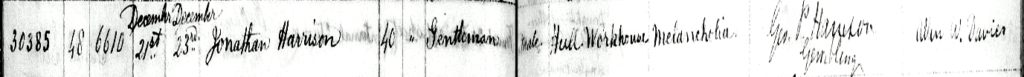

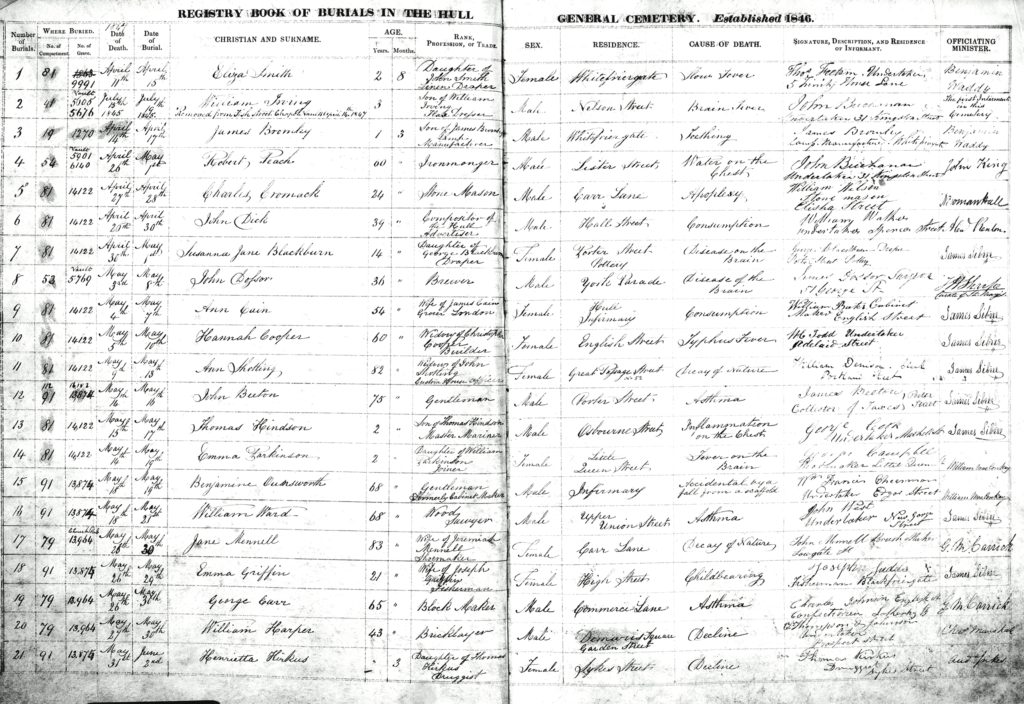

Here’s the first page of the Hull General Cemetery burial records. Note the grave number 14122 in compartment 81. This is the first public grave in the cemetery. The one that was dug to a depth of 11 foot 6 inches. The first burial was of the stonemason as mentioned above. Burial number 5 in the cemetery. Charles Cromack. And then John Dick, Susanna Blackburn, Ann Cain, Hannah Cooper, Ann Shefling, Thomas Hindson and finally Emma Parkisnon. In total eight people, two of them infants.

In this way the poor who could not afford to buy a family grave were still buried with dignity. Look at the small part of Compartment 81 shown. Public graves were not placed in the ‘wilderness’, far from the wealthier patrons of the cemetery. There was a democratic feel to the placement of such graves. They were made to feel just as much a part of the community as the person who afford a family grave. This was one of the positives of the Hull General Cemetery. Public Grave, Public Shame?

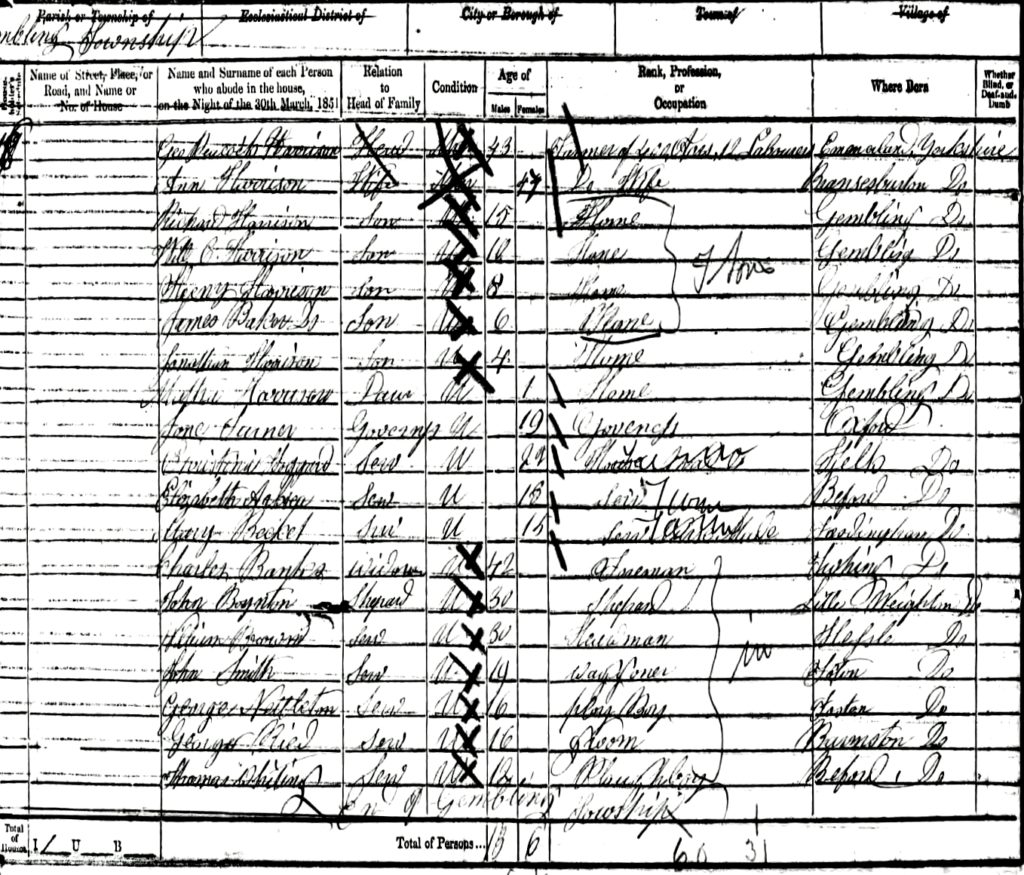

1851

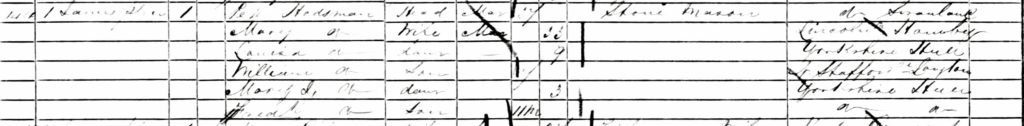

By 1850, Peter may had found work with the Cemetery Company. Sadly, we do not know. However, he was listed as a stone mason in the census of 1851 as the image below shows. His address was Eliza Place, Walker Street and this was quite close to a stone yard in Great Thornton Street. The owner was a J.C.Scorer, so perhaps Peter worked closer to home. His daughter Elizabeth, cited in the census, would not survive the year.

Education, education, education

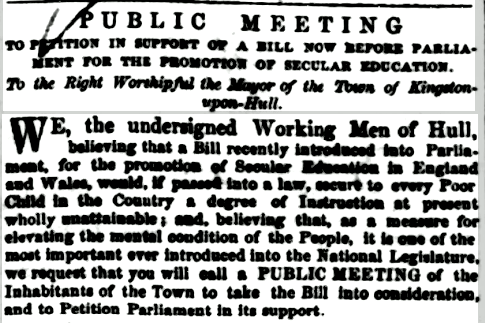

The next we hear of Peter is in the local newspaper. He is one of the signatories of a notice requesting that the Mayor, Thomas William Palmer, calls a public meeting. This aim of this meeting was to petition Parliament with regard to children’s education.

This idea was well before its time. The free schooling of children did not occur nationally until the passing of Forster’s Education Act of 1870. That Peter was a supporter of this idea is interesting as one of granddaughters went on to become a school teacher in the late 1890s.

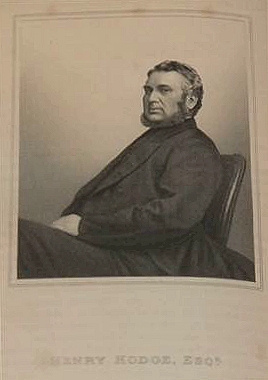

The petition was signed by more than 500 ‘working men’. The Mayor duly called the meeting for the 15th April at the Town Hall. It was a rowdy meeting. The purpose of the meeting was as set out above; namely the education of every child via a secular system. The Mayor outlined this idea and how it was progressing through Parliament. A Mr T.D. Leavens, a foreman at the Minerva Oil Mills, seconded the motion. He also observed that,

‘this was the first public meeting ever convened by a Mayor of Hull in compliance with a requisition from the working man.’

Secular versus religious

An amendment was put forward. The proposer, Mr Frederick Smith, contended that secular education on its own could not work. It needed to be balanced with religious education too. This attempt met with some serious disapproval from the audience. Some of the audience felt that the motion was being derailed by this suggestion

The intervention of E.F. Collins, noted editor of the Hull Advertiser, appeared to take the sting out of the amendment and his words brought much laughter. The motion was carried and the Mayor was entrusted to pass on the wishes of the townspeople of Hull on this issue to Parliament.

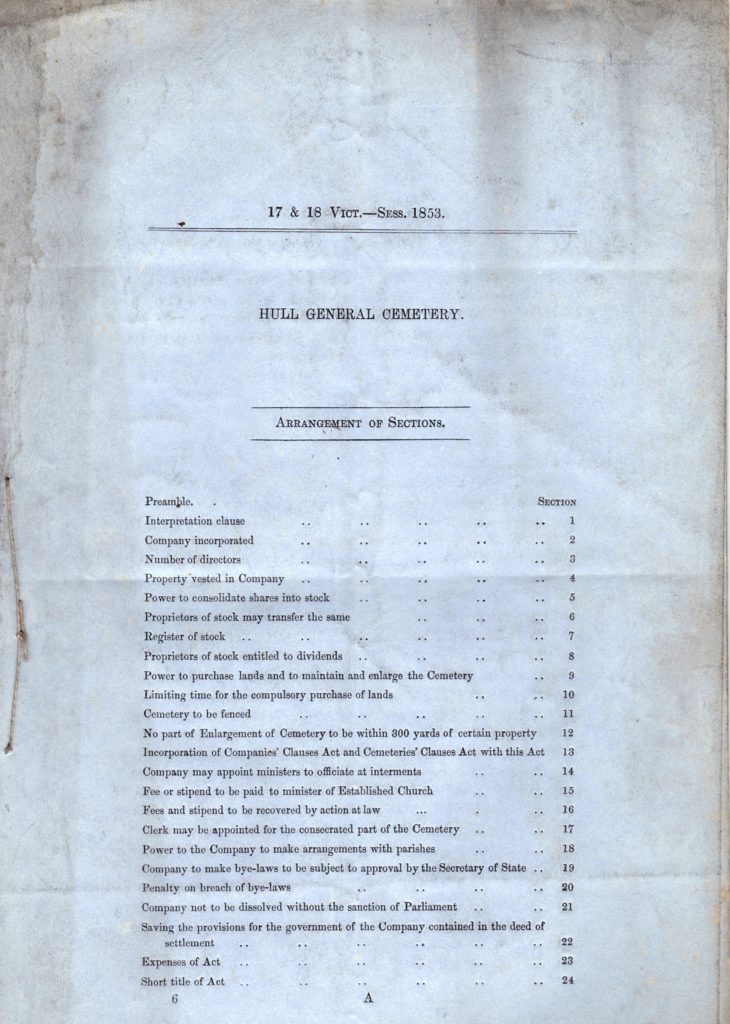

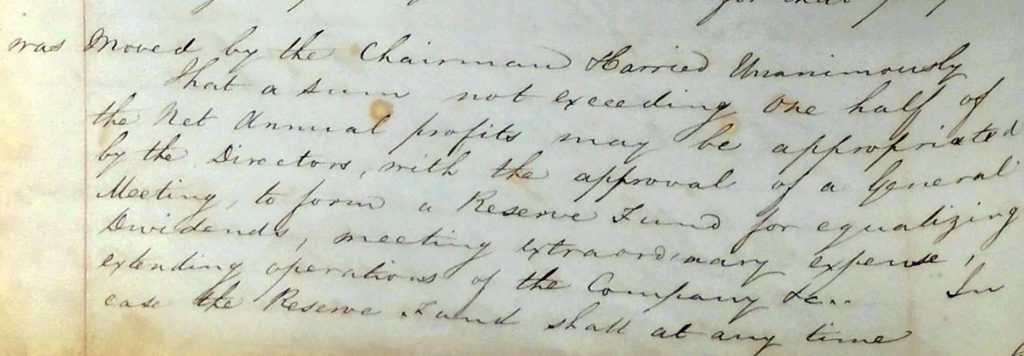

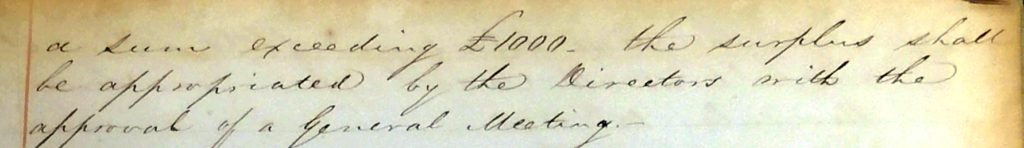

Enlargement of the stone yard business in the cemetery

Meanwhile, in December 1852, John Shields requested that,

‘An enlargement of the Mason’s Work shed was now essentially necessary in consequence of the great interest in the Company’s stone business and that the same must be made forthwith and he having also produced an estimate of the expense of such an enlargement amounting to £20 1s, and the question having been considered and discussed it was resolved that such enlargement be forthwith made and that the costs be charged to the alterations account.’

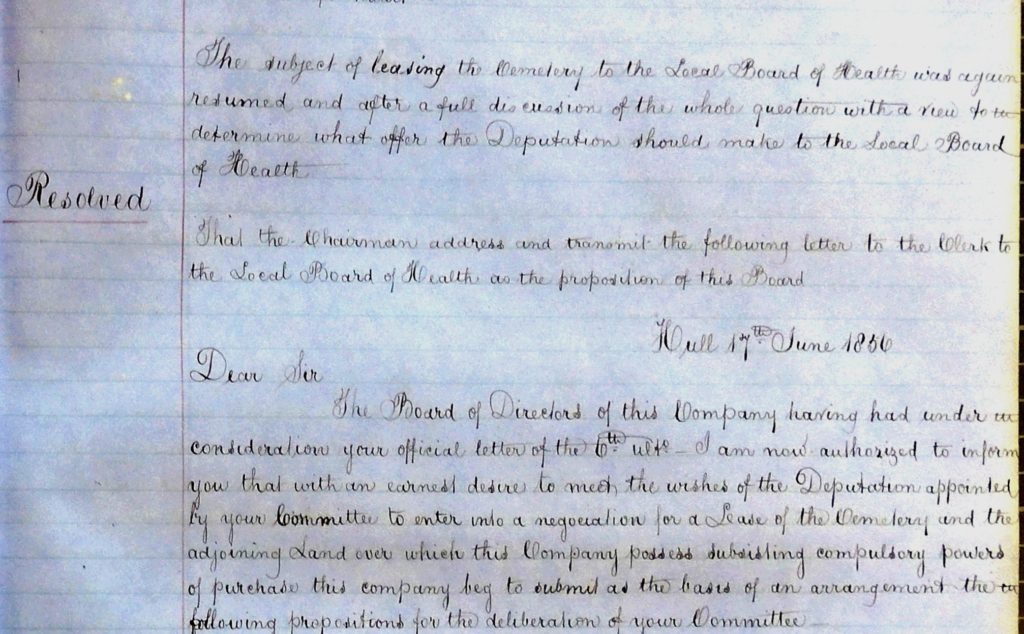

The Company’s stone business was well and truly taking off. As we saw previously, by 1856 the Company were amenable to selling the Cemetery to the Corporation but they wanted to keep the stone yard business. An Anniversary: June 1856

In September 1853 three apprentices are taken on in the stone yard. Peter is not one of them but he was a fully trained stone mason by now so he would not be taken as an apprentice.

1861

Peter’s census return of 1861 is below and shows a change of address. The notice below is a poor reproduction.

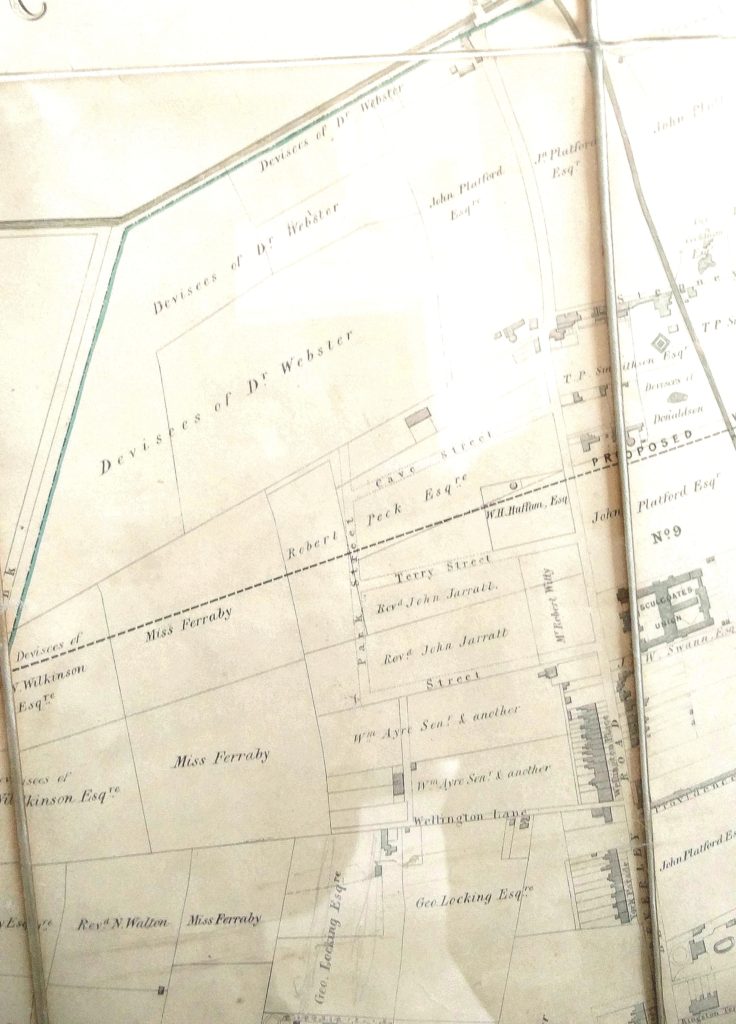

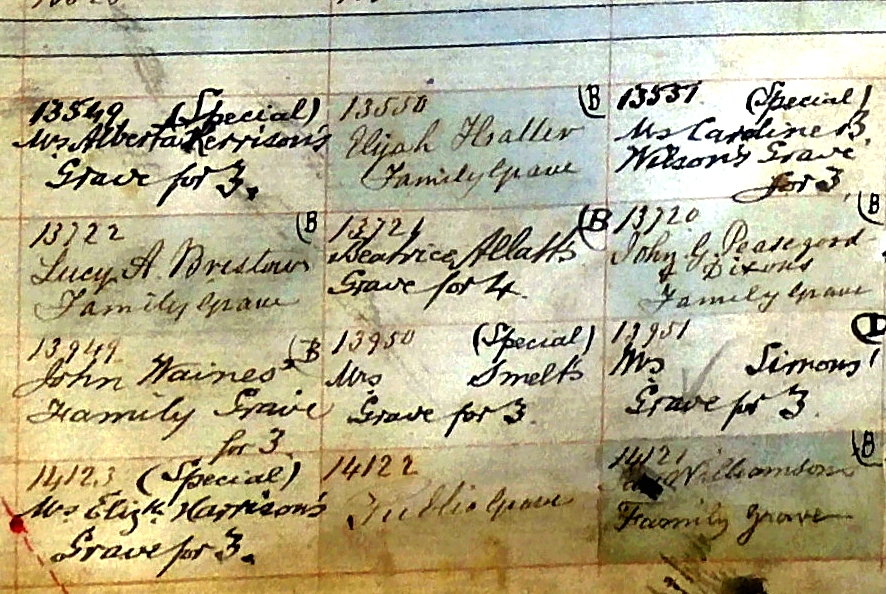

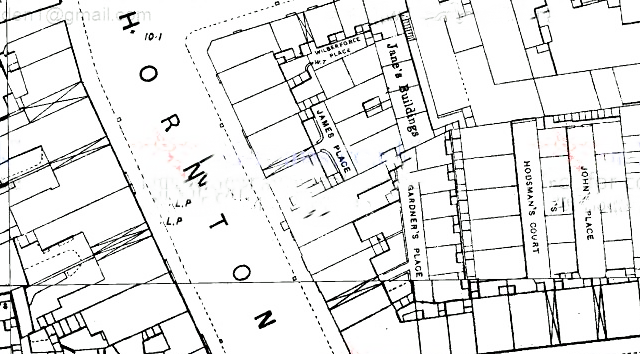

The information recorded is that Peter and his family now live in Great Thornton Street at 1, James Place. Interestingly he lived next to Gardener’s Place where my great great grandfather lived around this time and just around the corner was Hodsman’s Court.

Family tragedies

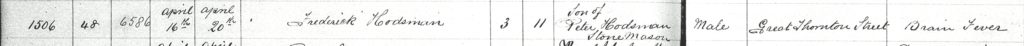

His family has increased. He now has two daughters; Louisa and Mary Jane, and two sons; William and Frederick. Sadly, in 1863, the family was struck by tragedy. Mary Jane died of smallpox. She was buried in the land that the Corporation had leased from the Cemetery Company in 1860.

A year later young Frederick also passed away of’ ‘brain fever’.

Amidst this sea of woe Mary Hodsman had another boy. He was called John Thomas and he features in this story.

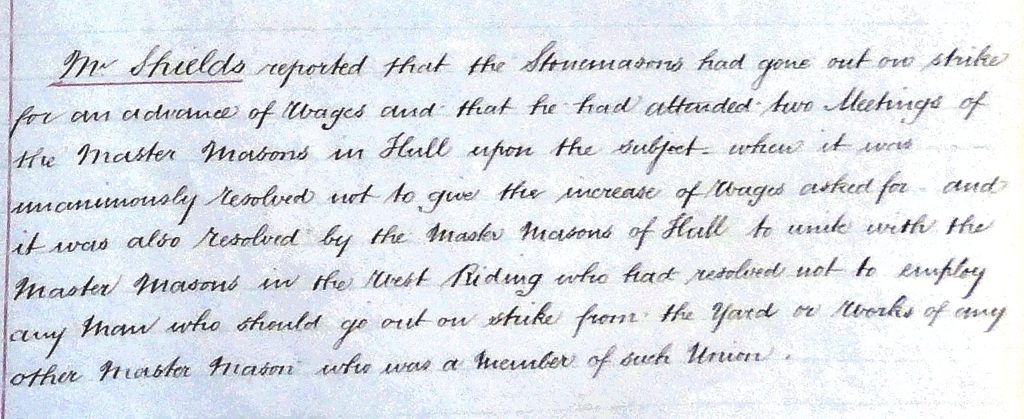

Strike!

Three months after Frederick died the stonemason’s of Hull came out on strike. This is poorly reported in the newspapers of the time and the only reference I can find is from the Company’s minute books. In this John Shields reported to the Directors,

We have no way of knowing how this turn of events affected Peter. Was he a striker? Was he a strike-breaker?

We do know that John Shields was in a bind due to this strike. He told the Directors that,

‘in consequence of the masons’ strike he was unable to execute the orders received for stone and granite work and that several parties were pressing to have their work done without delay.’

The Directors agreed with his request to go to Aberdeen, which was where most of the Company’s stone came from, and seek out a qualified ‘letterer’. He duly did so,

‘And had engaged a man named James Mitchell as a mason and letter cutter for the company at the weekly wage of 30/- ‘

Solid evidence

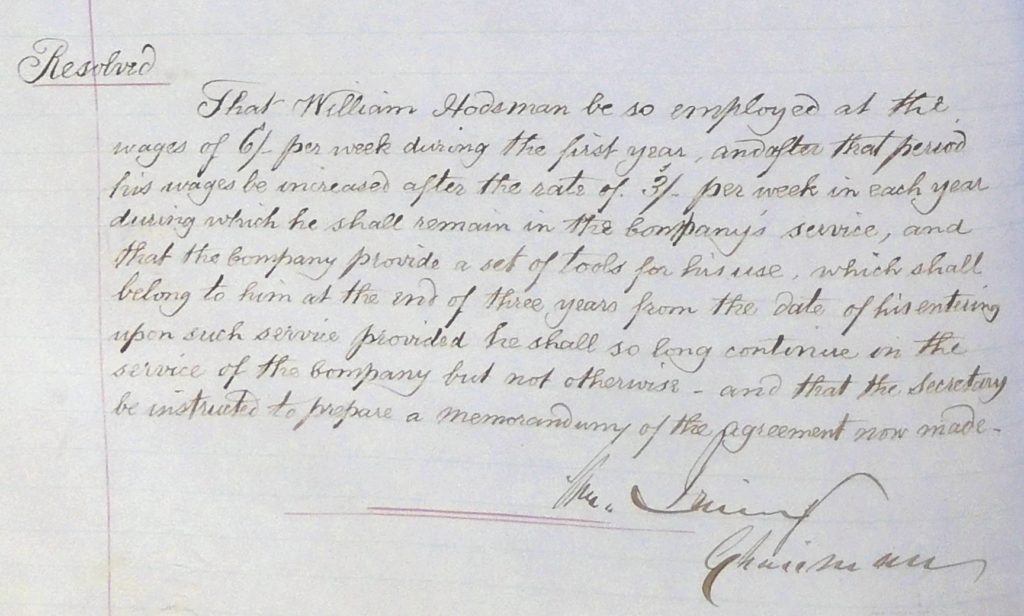

Our next entry is where Peter and the Company arrive together. At last, concrete proof that Peter was a stonemason of the cemetery. On the 3rd April 1868 the secretary,

‘Read a letter from Peter Hodsman, the foreman of the stone masons, asking for an advance of wages’.

The decision was stood down till the next meeting. At that meeting his wages were increased from 35/- a week to 42/-. A considerable increase of a fifth. This probably shows his worth to the Company. That Peter wrote them a letter requesting an increase in his salary must have impressed the Board.

In the following August another event took place. Peter asked the Board if his son William could be an apprentice stone mason. The appeal was successful. William at this time was barely 14 years old.

1871

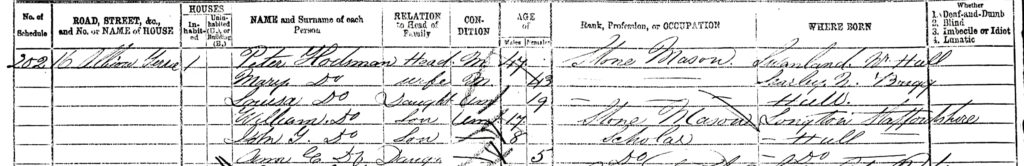

We next find Peter at home in the census of 1871. His home now is in Albion Terrace in Walmsley Street, Spring Bank. A larger property in a better area but still not of the best kind.

As can be seen, the Hodsman family had increased again. Another daughter, Anne Elizabeth, had been born in 1866. William, the eldest son, is classed as a stone mason like his father.

More tragedy

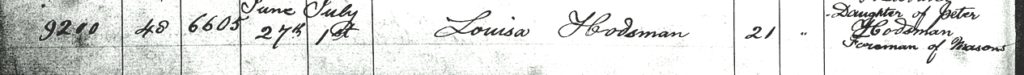

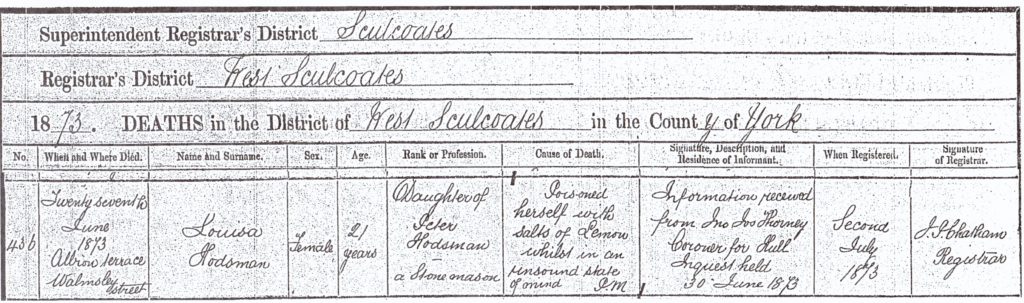

Tragedy hit the family again in 1873 when Peter’s eldest daughter, Louisa died at the age of 21.

This is the first mention, outside of the minute books, that Peter is now the foreman of the masons for the Cemetery Company. Peter signs as the informant and characteristically calls himself ‘mason of letterers’.

The burial entry is interesting No cause of death is cited. The reason for this may be simple.

Louisa sadly committed suicide ‘whilst in an unsound state of mind’ She consumed a quantity of poison, ‘salts of lemon’, and died. That the cause of death was not entered in the Cemetery burial register may well have been a show of sympathy from the superintendent, Edward Nequest, respecting Peter’s feelings, and not placing the mode of death in the ledgers for posterity.

In the August of 1877 Peter once again approached the Board to have another son apprenticed. This son was John Thomas. Once again they accepted him on the same terms as they had accepted William. The following year Peter’s eldest son William married. His wife was Emma Marie Cole. Peter moved home again to 2, Stanley Street, Spring Bank. Closer to work and a better house.

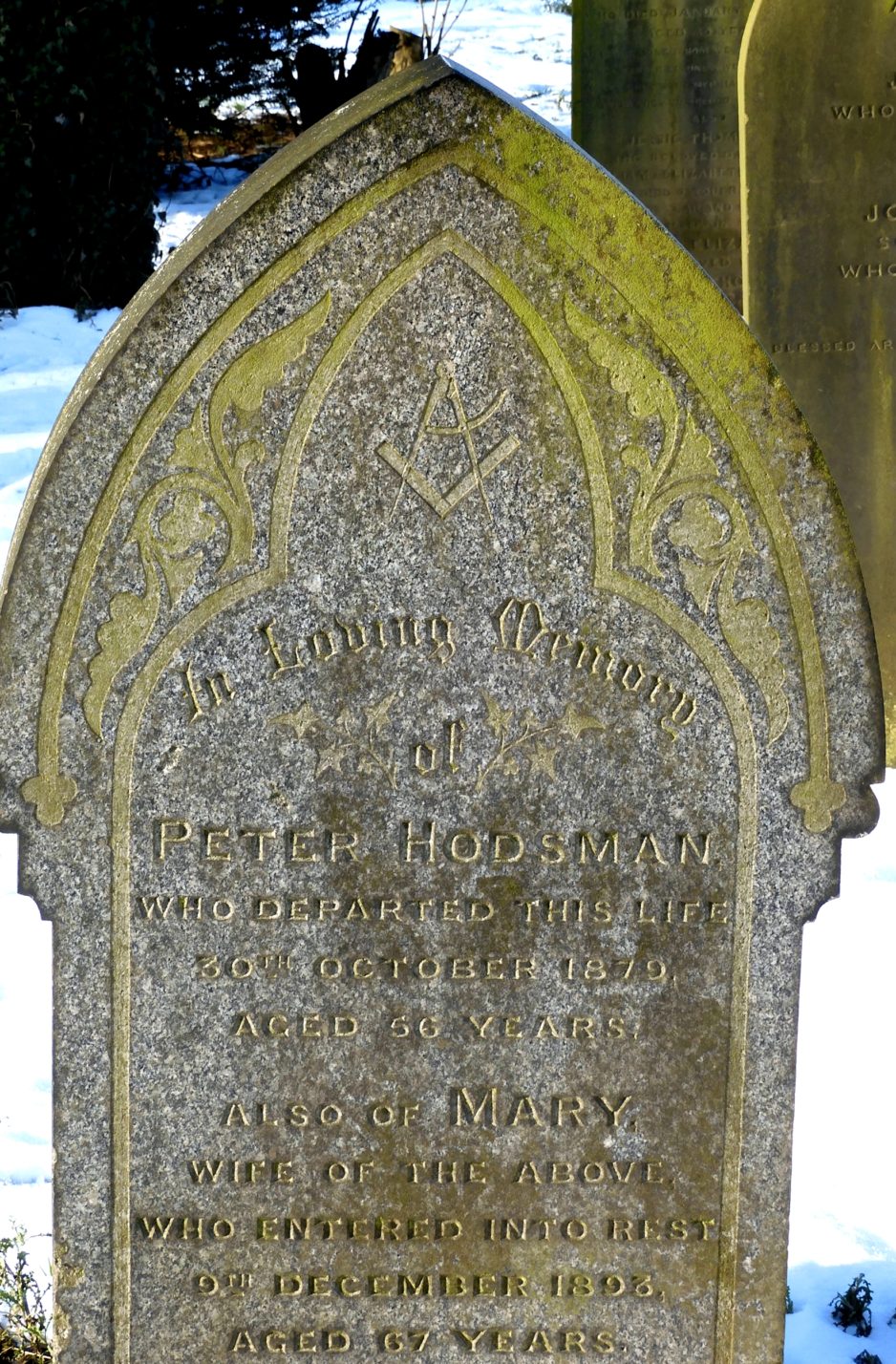

Peter’s death

By the winter of 1879 Peter was not well. He fell ill of chronic bronchitis. The result no doubt of too many days spent doing hard labour in cold weather. He was also suffering from heart troubles.

Peter died on the 30th October. He was buried in the same grave as his daughter Mary Jane and his son Frederick. His wife must have demanded that a burial space be left for her in her husband’s grave. When Louisa dies she had been buried in the grave next to the original family one. Mary wanted to lie, in death, with her husband. A sure sign that neither partner wanted to be separated even in death.

Peter left a will. His estate was under £1000 but he left his family some funds to carry on. The executors were as expected his wife Mary and his son William. One other executor also appeared. That of Edward Nequest, the cemetery superintendent. I would take this to indicate how much either man thought of each other. It also showed how much the Company thought of Peter in giving Mr Nequest the time to go to Court in York to have the will proved.

Epitaph

When you read a headstone in Hull General Cemetery and it is dated before 1879 there is a good chance that Peter carved those words. When you see a headstone from before that date with the ‘Cemetery Company’ inscribed on it you see the handiwork of this man. This man would have inspected all of the work or done it himself. His legacy will, with careful husbandry, outlast us all. He was, after all, a stonemason of the cemetery.

His burial record stated his occupation as ‘Manager Monumental Works, Cemetery Co.’

This epithet appears a mite too grand. I’m pretty sure that if Peter could have written it, it would have said simply, ‘Stone mason’. I’m also pretty sure that Peter was proud of that simple title.

William, his son, signed the burial register as the informant. ‘Monumental letterer’ was what he called himself. I’m sure his father would have been proud.

William and his brother John’s story will be told next month.

Pete Lowden is a member of the Friends of Hull General Cemetery committee which is committed to reclaiming the cemetery and returning it back to a community resource.