The Creation of Hull General Cemetery: Part One

I wrote this article in 2015 back in a time when Nick Clegg was the Deputy Prime Minister. It was published in six parts in the Hull Civic News in 2016 back when the country was still European. As Dylan sang, ‘The times they are changing’ but I think even he might not have foreseen such changes occurring since I sat down at the keyboard and started typing this story.

I’ve revised the article here and there for this website. You may find some comments slightly out of kilter, such as the state of the cemetery at that time I was writing, but I thought they should be left in. It shows the progress that has been made. Finally, I’ve divided the story up into three parts for ease of reading. The other parts will follow in the next couple of months.

This is a brief overview of the creation of Hull General Cemetery, with some personal views.

As a young child I used to love walking to Hull Fair every October. One of the delights was to kick my way through the large drifts of fallen leaves along Spring Bank West. These had fallen from the many over-hanging trees on the Hull General Cemetery side. Of course, I never strayed too far from my mum. Even though the Cemetery had a large wooden fence enclosing it, it was still a dark, scary place to be next to. Especially without the reassurance of a grown up. But the cemetery itself exercised a fascination. It was as much a part of the ‘fun of the fair’ as candy floss and the big wheel.

I suppose the attraction of it, for me at that age, was that I loved history. By far my favourite subject at school, I was in awe of historical ‘things’ and I could see that Hull General Cemetery was old. Therefore, to me, it was valuable, just as much as dinosaur bones or the Crown Jewels were. But even better, this history was here in Hull.

1977 and all that

Moving forward, some 20 years from that time, I worked for Hull City Council. I was employed as a gravedigger. Firstly in Northern and then Western Cemetery. The Council began its despoliation of the Hull General Cemetery whilst I was working for the Council. This destruction was done in the name of progress, transforming something precious into something mundane.

You may want to read ‘A Monumental Loss’ elsewhere on this site for a fuller picture of that travesty. A Monumental Loss

History is bunk

Working in Northern Cemetery at the time I’d sometimes get off the bus at Western Cemetery and walk home. The route home was through Western and HGC. I was a union rep at the time so this journey was not simply a whim. The health and safety of my members was important and I wanted to check up on this. So, a walk home was sometimes the only way I could do this. I noted the destruction that was taking place there with every step home. And every night I knew that something precious was being lost.

I can still remember one senior member of the Leisure Services Department telling me at the time that if he had had his way the entire site would have been cleared; no ifs or buts. Henry Ford once said, ‘History is bunk’. It would be fair to say the Council at this time agreed. This was long before the ‘heritage’ industry was seen as a money spinner for local authorities. However, even at the time, just a quick look up the A1079 to York might have enlightened the elected members somewhat.

Today ( but actually 2015)

Now the site seems to be a multi-functional ‘community resource’; as a dog walk, a cut through to the Dukeries, a place for both ‘serious drinkers’ to frequent and drug users to hide their habits away from prying eyes. Principally it has now become an unofficial rubbish dump. Was that what that tide of destruction was for?

I am not anti-dog. Far from it, I have owned dogs most of my life. Nor do I refuse to take an alcoholic drink without a good reason. I am also aware that the Council runs quite an efficient waste disposal sites. They’ll even come to pick up items from your house. So how did we come to exchange a rare resource for the above?

I am pretty sure that the Council did not envision these limited outcomes for the Cemetery when they cleared it back in 1977/8. We cannot undo the harm that officialdom did 40 years ago. What we can do is cherish and protect what we have now. The Hull General Cemetery site is still an historic asset. It should, and could, be treat with more dignity and respect.

Enough pontificating, let’s look at how and why the Hull General Cemetery began.

Burial practice and sites

Almost all burials, throughout the Christian period in the British Isles, were undertaken within the consecrated ground of the parish church or the grounds of a religious order. It was an inalienable right within the common law to be buried in consecrated ground within one’s own parish The exceptions to this were few and far between.

The most numerous of these exceptions would have still born births. If the child had not been baptised it could not be buried in consecrated ground. A harsh ruling but the Church was very strict that any burials within consecrated ground should be of people who had been baptized as Christians.

Suicides were sometime excluded as this was also seen as strong sin against God. In that the individual was taking unto themselves the time when they should die rather than leaving that to God. However, this was not a hard and fast rule. Space was made available for such deaths, usually in the Northern part of the church yard, to accommodate such burials.

The other major grouping who would have failed to be buried in consecrated ground would have been rebels or traitors and, as can be imagined, these were few and far between over the centuries.

The religious orders

The other main burial area during the period up to the Reformation was within the confines of a religious Order. There were three such places in the vicinity of what is now Hull. The Carmelites had a Friary situated on the land that now stretches between Posterngate and Whitefriargate. Their tenure of this piece of land is still remembered by the street name. Burials took place here and excavations in the early 19t century uncovered such burials.

The Carthusians were based at the Charterhouse. This chapel of this site was used for burials up until the mid 19th century. The final religious order in Hull were the Augustinians. Their clothing, or habit, was black and they became known as the Black Friars. Their base was close to the east of the old Market Place. Not surprisingly they too gave their name to the street where they were based. Blackfriargate has almost disappeared but it is an historic Hull street. It was excavated by the Humberside Archaeology unit in the early 1970s. Many burials were found to have taken place there.

Syphilis and suppression

Of interest, a number of the skeletons excavated at this site showed evidence of syphilis damage. As these people were buried well over a century before the sailors of Columbus were supposed to have brought back this disease from the New World this discovery has caused some old beliefs to be re-examined.

The suppression of the monasteries, in the 16th century, obviously ended burial within such institutions. The only burial place available to the population after this was the parish church yard. Until the end of the 17th century that is.

Non-conformists

With the rise of non-conformism, and the splintering of that into its myriad forms, another option began to present itself. Commonly called Dissenters, in that they objected against the teachings of the Established Church. they wanted no truck with burial in consecrated ground.

As such these sects looked towards providing another form of burying place for themselves. These burial places had to be outside the consecrated ground of the church. As an example, in Hull the Quakers purchased some land, in what is now Hodgson Street, for the burial of their members. Other denominations built chapels to cater for their religious meetings. In the vaults below the chapels, they laid their departed members to rest in them.

Population increase

This system worked well enough whilst the population of towns outside of London were relatively small. At the turn of the 19th century Hull had a population of around 20 to 25,000 people. It could have conveniently fit into the KC stadium. However population was on the rise and not just in Hull.

Without over bearing this article with too many figures, some may be useful here. I’m using the Victoria County History here, Volume 1. It states that Hull and Sculcoates in 1700 had an estimated population of 7,512. A century later this had increased to 25,613. By the time of the first census in 1801 this figure was 22,161. In the 1831 census the population had almost doubled to 32,958. By the 1841, some six years before the Hull General Cemetery opened its gates, the population stood at 65,670. In essence the population of Hull and Sculcoates had almost trebled in 40 years.

With the increase of population, space was at a premium in the small, enclosed parish churchyards and burying grounds of the Dissenters throughout the town.

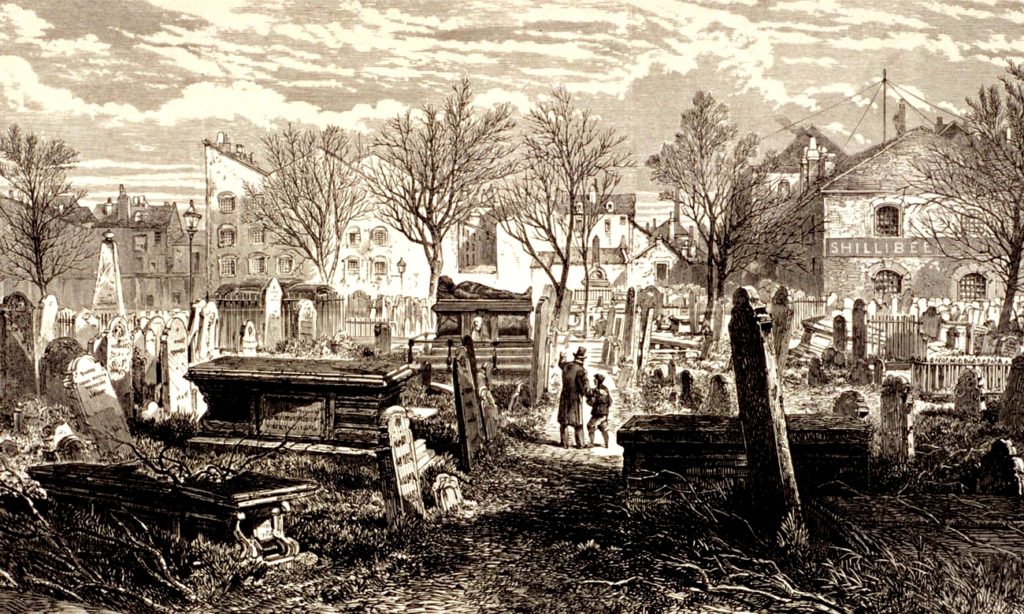

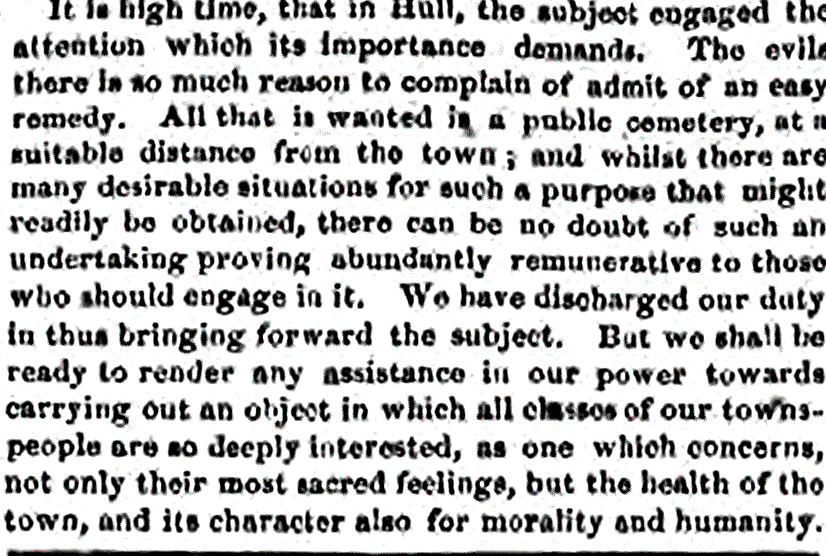

Below is an image of Bunhill Fields in London. A Dissenter’s burial ground since the 1660s, by Victorian times it was notorious. Daniel Defoe is buried there. It provides a graphic example of how poor and overcrowded the small burial grounds were at that time.

The dignity of the dead

The disposal of the ever-increasing amount of the dead, began to be a major problem. Their disposal suffered a fall in the dignity which should have been shown to them. Hull and Sculcoates were not immune to this rough and ready treatment of the dead.

Holy Trinity Church, by the 1830’s, had for its interment use, the ground surrounding the church in the Market Place. This site had been used for burial since the foundation of the church in the 13th century. It later acquired in 1783 some 3 acres of land on Castle Street as a new burying ground. However, all of these burial grounds that were associated with Holy Trinity were full by the 1830’s.

St Mary’s Church in Lowgate had its own churchyard on Lowgate. It also had the small Trippett Street burial ground of approximately a quarter of an acre. In later years this site was levelled off and the burial ground found another use. It was used, in the recent past, as a backdrop for the wedding photographs after the wedding at the local Register Office. This burying ground had been opened in 1774 but by the 1830s it too was full.

The only other Anglican burying sites in Hull and Sculcoates at this time were the churchyard of St Mary’s, Air Street, which was also full by this time, and the new burying grounds for this parish church in Sculcoates Lane. This was situated on the south side of the road and was opened in 1818. On the east side of the River Hull, St Peter’s in Drypool, was also struggling to bury the parish’s dead.

The burial grounds were full

For all of these sites, the same problem arose. How can you carry on burying the dead in a ground that is already full. There appeared to be no answer. The churches did not want to forgo the revenue that burials in consecrated ground gave them so turned a blind eye to the despoliation of the dead by the sextons and gravediggers. For, to accommodate the next burial, the previous one had to be hacked away.

Burial space was at a premium and managing to inter a body must have been something of a work of art. Foster, in Living and Dying, cites an example of a burial in St Mary’s Churchyard in 1844 where the previous occupants of the grave were all taken out and stacked in the church whilst the gravedigger presumably deepened the grave to accommodate the previous occupants plus the new internment.

He also states that correspondents to The Hull Advertiser of the time were constantly informing the editor of the latest indignities heaped upon the dead in Hull. Just a thin scattering of earth over the next occupant of the grave was all that seemed to be required. There are tales of dogs, pigs and rats haunting burying grounds. An image that can best be left to the imagination. One commentator of the period said, of churches generally, that they looked like they had been built in pits, so much had the ground around them been raised up by burials.

Funerals

Funerals began to take on their present appearance about the 1830’s, concurrent with the rise of the privately funded cemetery such as the Hull General Cemetery in Hull and others across the country. Indeed, it can be argued that this burst of urban cemeteries that, later in the Victorian period, gave in some senses, the impetus for the rise of the ‘funerary industry’.

Of interest, at least in terms of fashion, was the dropping of the term “burial or burying ground” to be replaced by exotic terms such as cemetery and necropolis around this time. In our modern, more cynical, times we would probably say that the death business had had a makeover.

Profit

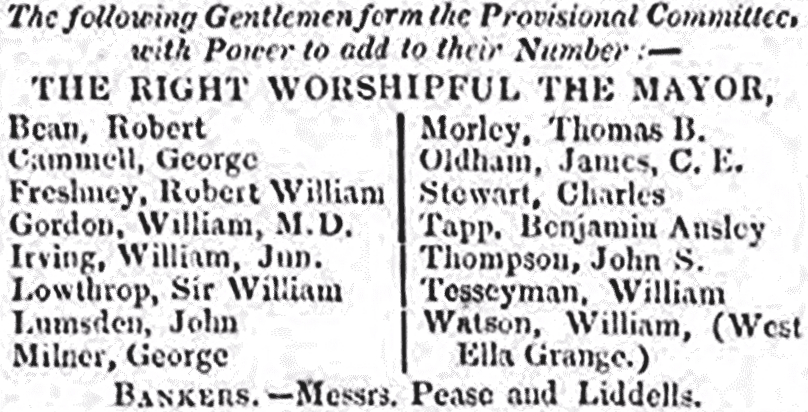

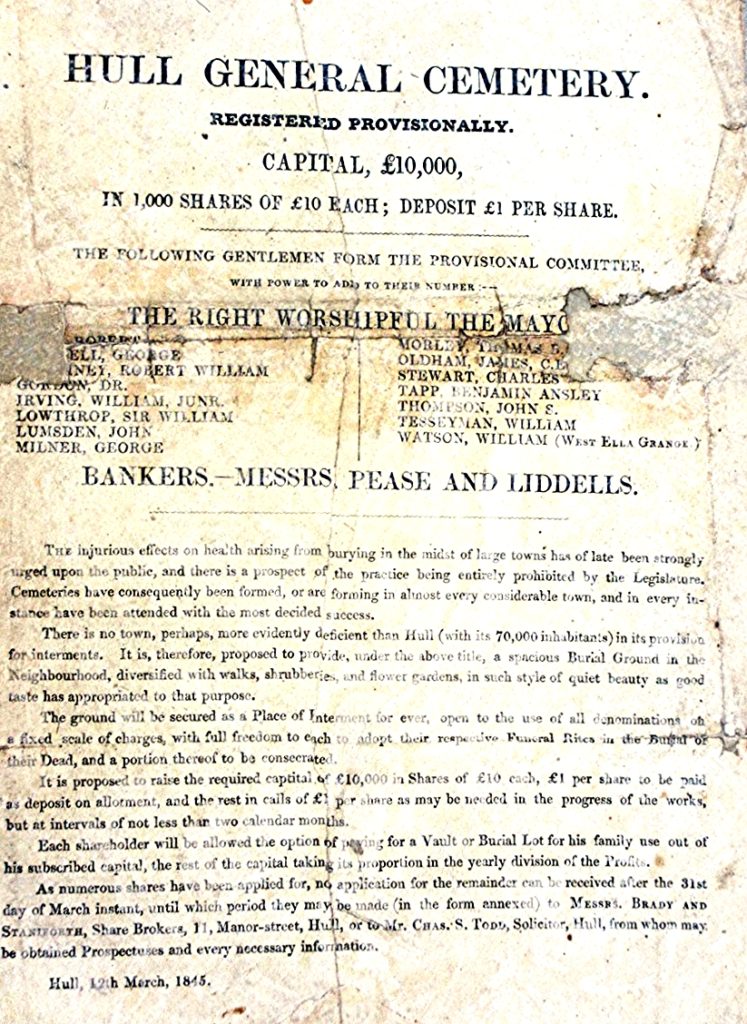

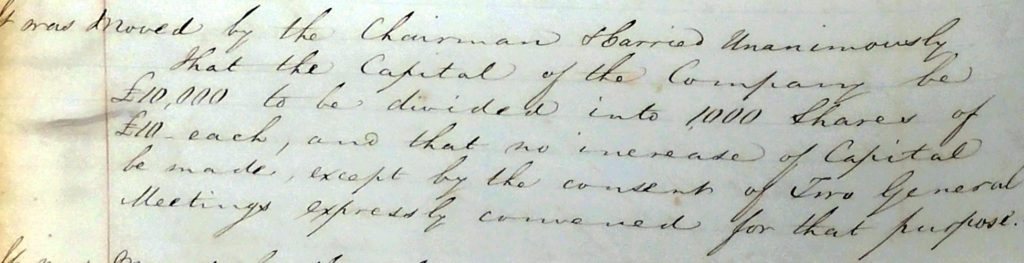

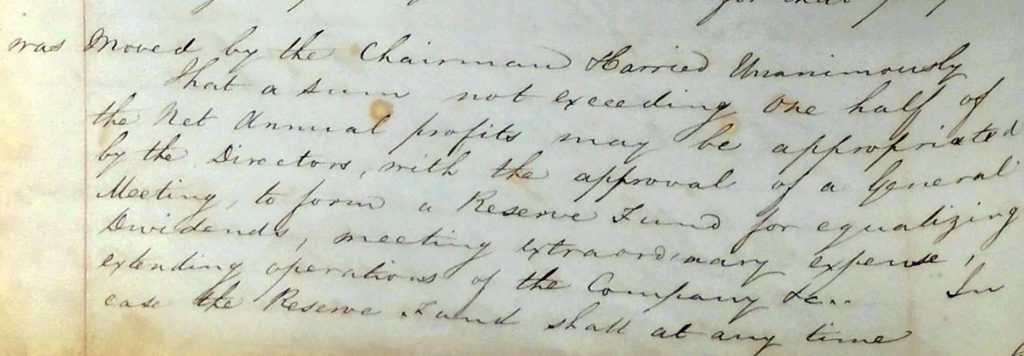

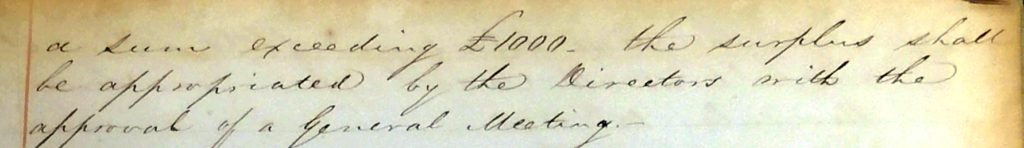

Cemeteries, run by a private company, were of course typical of the Victorian sense of laissez-faire in most things. That such a thing as the disposal of the dead should be left to a private company, and that a profit could ensue from that activity, was seen as natural. Accordingly, entrepreneurs usually joined together to form joint stock companies issuing shares in the company. The individuals who bought shares would then expect a dividend from their investment. It was this profit motive that gave a great deal of the impetus to the creation of many of the Victorian cemeteries of Britain that we can still see today.

Civic pride and cemeteries open to all

Another major force, apart from the hygiene aspect already alluded to, was the growth of civic pride. This pride, that obviously manifested itself in the erection of the municipal palaces that masqueraded as town or city halls. It also wanted museums, libraries, parks, market halls, boulevards and prisons to embellish their respective centres. Concurrent with this was the need for great urban centres to have a cemetery that could command respect amongst its equals. And so, the growth of cemeteries across the country was assured.

The other aspect that cannot be ignored is that these cemeteries were non-denominational. They endeavoured to cater to all Christian faiths. The idea behind this non-exclusivity of burial was one of the greatest draws of a general cemetery. Firstly, from the public’s point of view, it allowed a dignified Christian burial for their loved ones in a pleasant surrounding. Secondly, from the proprietor’s point of view, it allowed a wider clientele and customer base. A win-win situation for all.

The pioneer private cemeteries

The first private cemeteries in Great Britain were sited to cater for the large urban centres. The first one was probably in Chorlton Row, Rusholme Road in Manchester. It opened in 1821 specifically for Dissenters. Made famous by The Smiths in the 1980s it is now a park. Burials stopped taking place there in 1933.

Another early claim to fame is the Rosary Road Cemetery in Norwich. Developed in 1819 but not opened until 1821. This last cemetery was 13 acres in size. It was taken over by Norwich Council in 1954 and managed so sensitively that in 2010 it was granted Grade II listed status. A lesson there for all such ventures. Sadly, much too late for Hull City Council.

Liverpool and local anguish

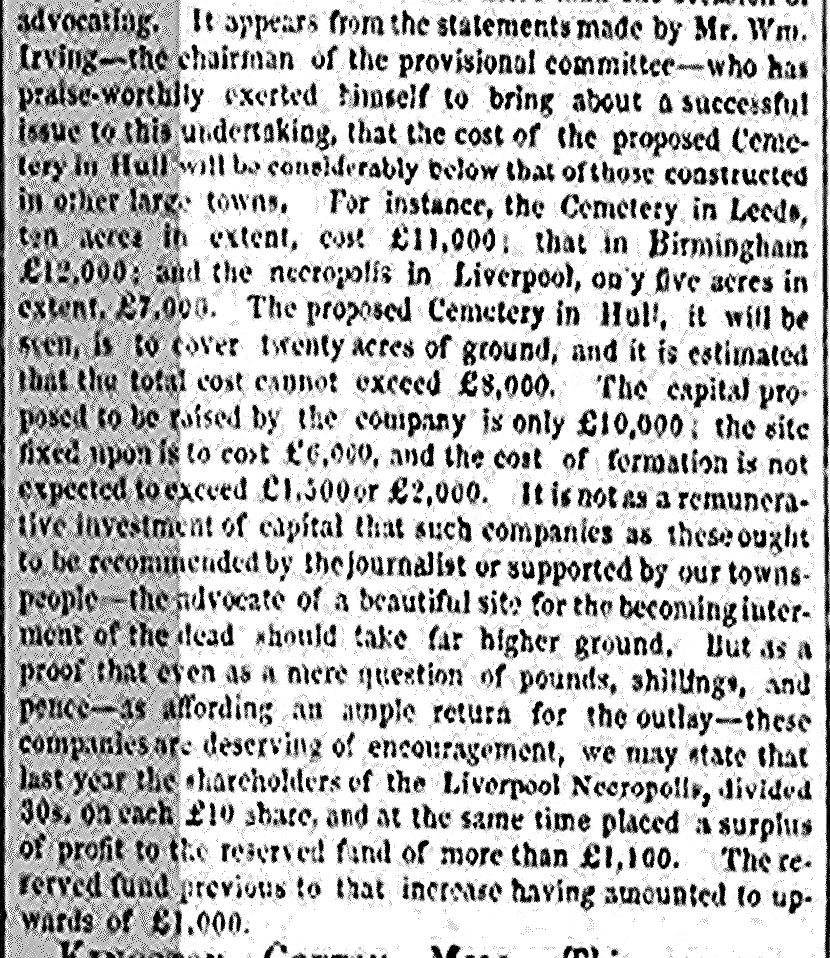

The Hull newspapers of the time reported such improvements of the town’s rivals. The death of William Huskisson, M.P. of Liverpool, who was also the first fatality of a rail accident in the world when he was killed at the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway on the 15th of September 1830, was widely reported. He was buried in the St James Cemetery in Liverpool. This cemetery had been opened the year before. It was large enough to cater for at least 50,000 burials. This was something to be marvelled at by the citizens of Hull. That this was the second large cemetery that Liverpool had opened in less than 5 years just added salt into the wound. The business opportunities that such a venture provided did not go unnoticed. The item from the Hull Advertiser of November 1833 highlights this.

Kensal Green

In February 1833 the news that a large cemetery was due to be opened in London set civic hearts a beating and was duly reported in the Hull Packet. That later on this cemetery was embellished by some of the most beautiful monuments outside of a museum simply increased the desire to emulate it in Hull.(1)

And further afield

In the July of that same year it was reported that some people in Leeds had formed a committee looking at this issue. It was reported that they were in the process of purchasing some land with a view to forming a general cemetery company. In the September the Bishop of Durham had given up some land in his diocese to be used as a private cemetery. By the November a news item stated that people in Manchester were to set up a joint stock cemetery company, the subscribed amount to be of £20,000 with shares at £10 each to create a much larger cemetery.

Much closer to home, it was reported, at the end of November 1833, that York was about to begin the process of setting up a general cemetery company. Even Malton began preparations to establish a general cemetery for itself in 1836.

By this time, even if there had been no pressing need for a general cemetery in Hull, there would have been a popular demand for one simply to maintain civic pride. That it took so long after this to finally open one is quite difficult to understand.

Cholera

One factor hindering the establishment of the cemetery may well have been that at this time (1832) the first attack of Asiatic cholera took place in the town. Although one would think it would have added impetus to the pressing need for a large cemetery, it may also have prevented economic growth. This was needed to finance and spur the project on. Without financial backing from the great and the good such an enterprise was extremely unlikely to take off.

Interestingly, when the second wave of cholera struck Hull in 1849, the Hull General Cemetery was seen as a godsend. In disposing and dealing with so many of the victims of the pandemic it assisted the town greatly.

In 1839 a reviewer of the book, “Gatherings from Graveyards” (2) in the Hull Packet stated that,

‘The Metropolitan burial places are pre-eminently considered: and well has the talented author asserted his notion that burying the dead in the neighbourhood of human habitations is a national evil… and as Hull at no distant day will proceed to form a cemetery worthy of our flourishing seaport.’

Stories in the press

During the elections of churchwardens for Holy Trinity the following April it was reported in the Hull Advertiser that it was, ‘hoped that before long a general cemetery would be here (in Hull).’

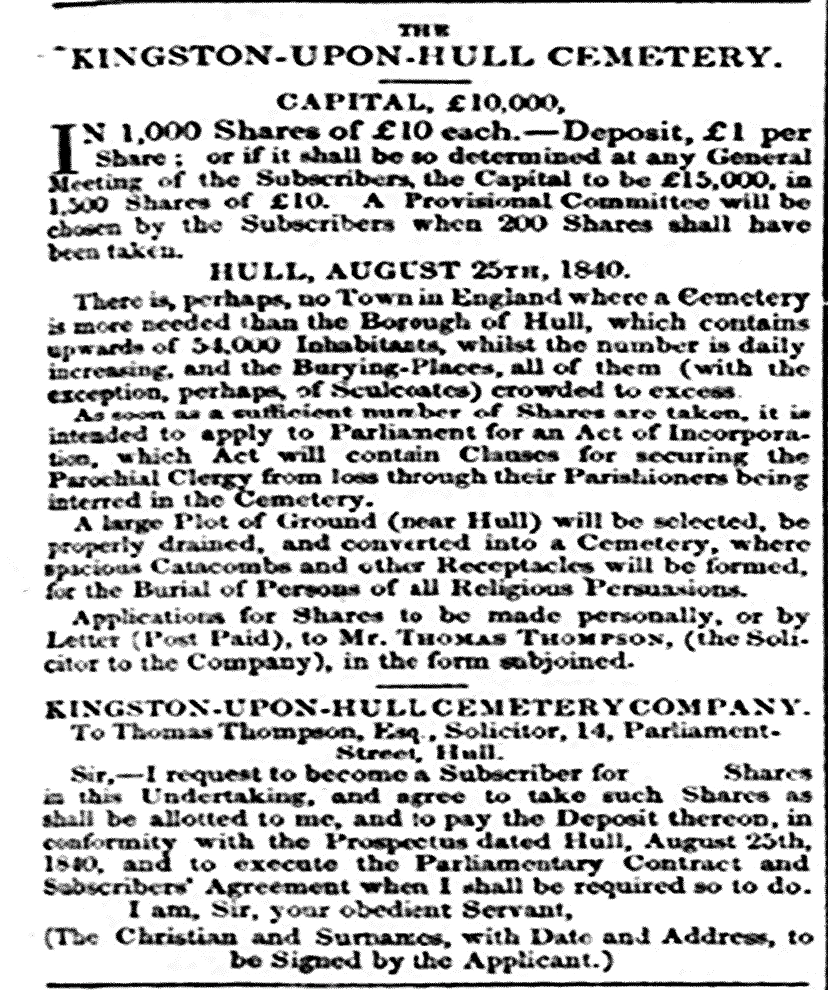

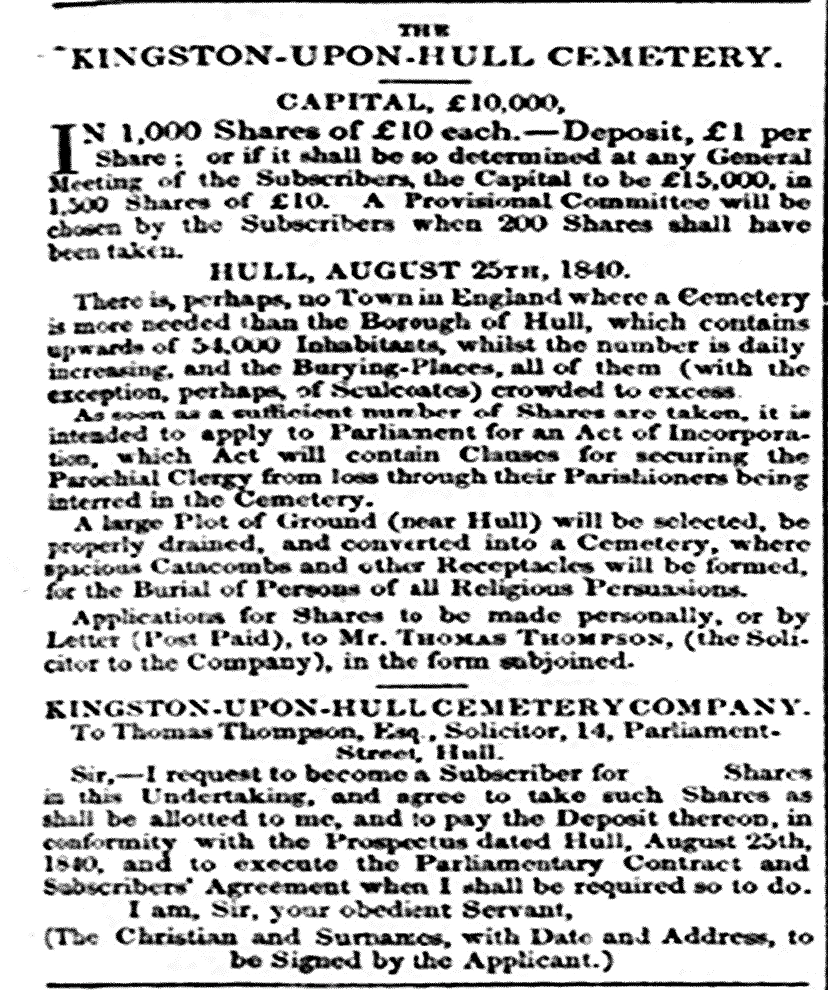

Finally, in the August of 1840, an advert, seen below, appeared in most local newspapers. This advert would have led to an outpouring of civic pride. At last a general cemetery was to be developed for the use of the townspeople of Hull and its neighbours.

The press reacted supportively and encouraged investors with the hope that,

‘We trust the support necessary to carry the object of the company into effect will be properly rendered… Public cemeteries have been rendered ornaments to the towns where they have already been constructed, and have besides, we believe, been found highly remunerative to the public-spirited projectors.’

In the Hull Advertiser of the next month, it was reported that the share list of subscribers was nearly complete. And there the matter appeared to rest. And die.

Doctor Gordon

In the Hull Advertiser in November 1841 under the interesting headline, ‘Noxious Effluvia’, Dr. Gordon spoke to the Hull Literary and Philosophical Society about ‘the effects of decomposing animal and vegetable substances upon the human constitution’. During this talk the need for a public cemetery for the town was again raised. Dr. Gordon, known as ‘the people’s friend’, was a noted advocate for a clean way to dispose of the dead.

Tragically he died young, in 1849, and was buried with much acclaim in Hull General Cemetery and his memorial was erected via public subscription. At its erection it was the largest monument in there and vied with the later Cholera Monument. Unfortunately, due to subsidence, it was reduced in 1900, to half its size.

To legislate or not

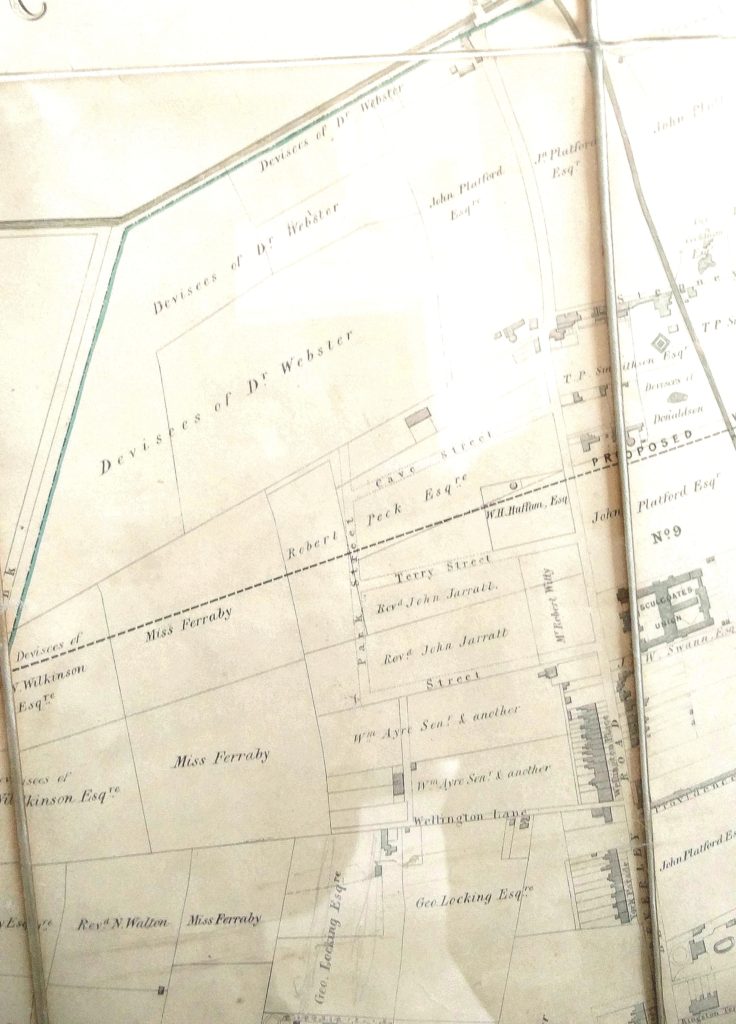

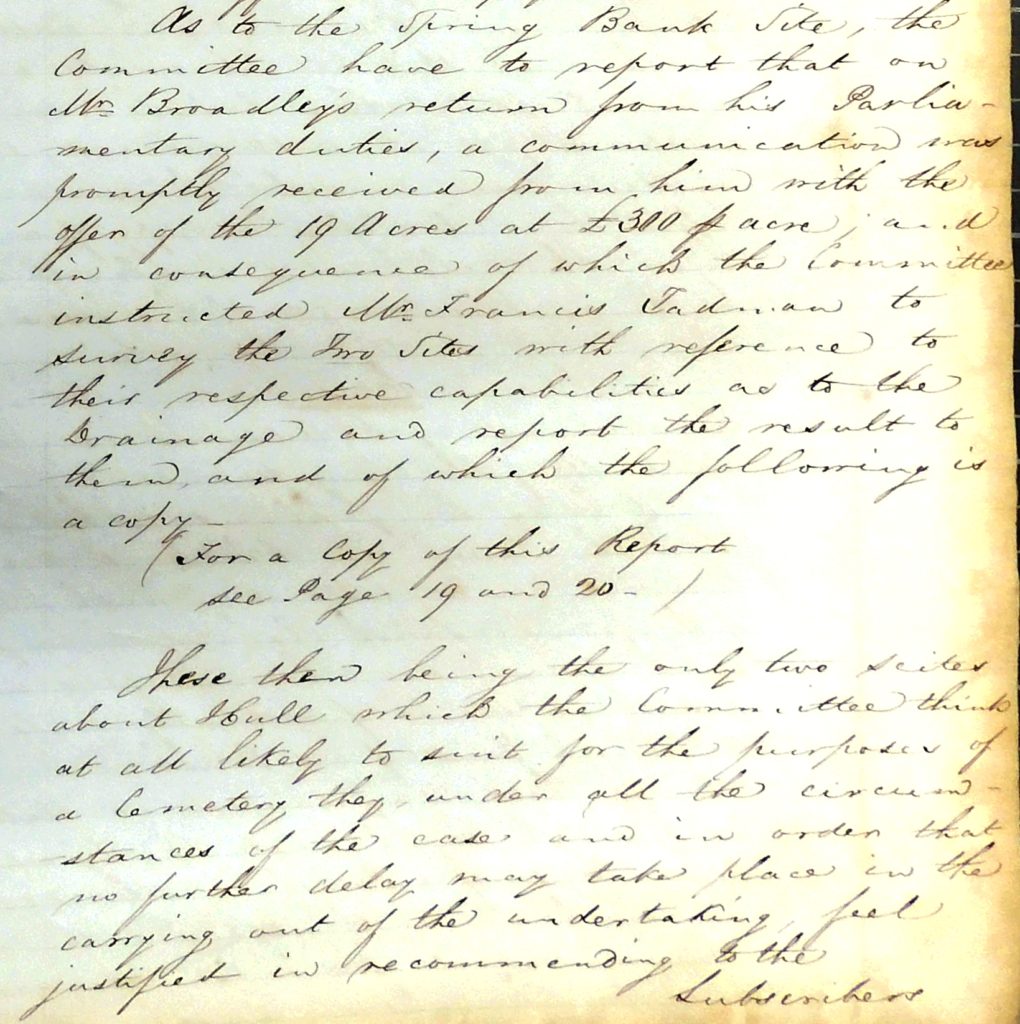

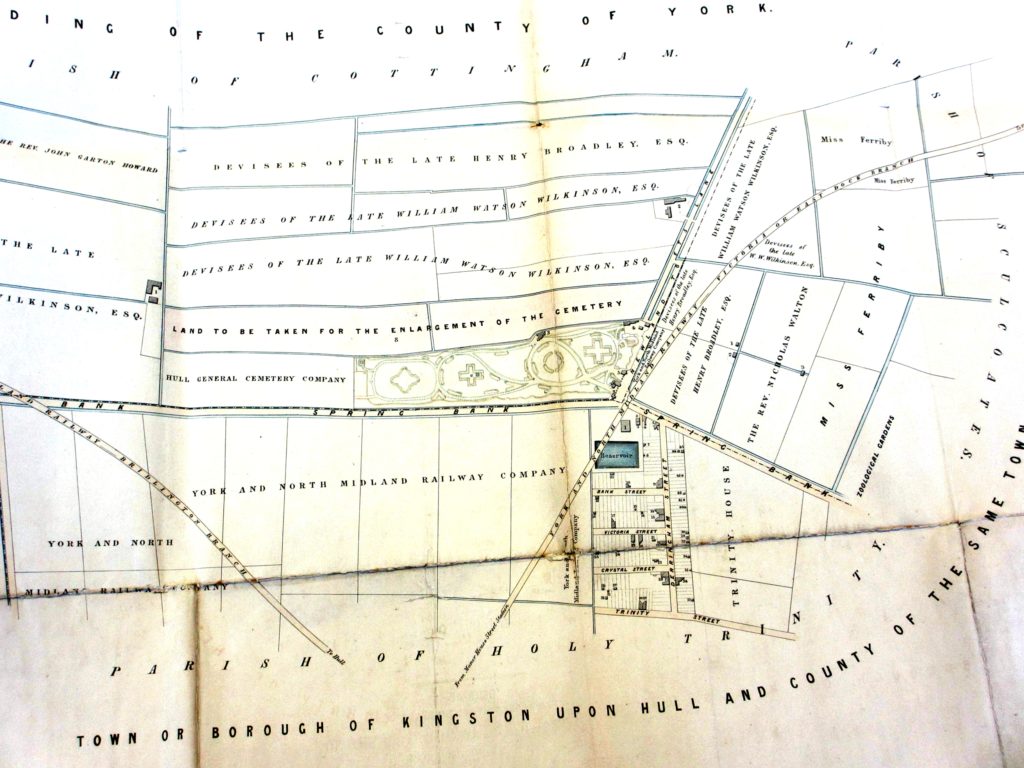

By the April of 1842 the whole idea of a general cemetery appeared to have disappeared entirely. Once again the Holy Trinity Churchwardens were discussing the need for a new cemetery. They believed that Mr Broadley had offered some 2 acres for their use. This was the beginnings of the Division Road cemetery but that was still twenty years in the future.

During this discussion the vicar counselled prevarication. Future legislation, regarding urban cemeteries, was going through Parliament at the time. By the June of 1842 a Parliamentary Select Committee, with Edwin Chadwick driving it, recommended that every large town should have a cemetery. However, that cemetery should not be “not within 1,800 yards of the same.” So, effectively the cemetery should be a mile outside the town. Of course, the Select Committee failed to notice the urban spread that the increase of population was driving. The urban centres would continue increasing in size and any future cemetery would eventually be swallowed up by urban sprawl.

By the April of 1843 this legislation was dragging its way through parliament. The ramifications of such legislation would make it a necessity that a general cemetery be established in Hull. After the legislation was passed it would be illegal, unless in a private vault, to inter anyone in a public churchyard or burying ground, that was not yet full, after the 31st December 1843. The same legislation made it easier for committees to be set up to purchase land, develop cemeteries and to run them. The door to Hull gaining its first general cemetery was not only open but there was a welcome mat just inside.

The Public Health Act 1848

This attempt at legislation failed. Further legislation, prompted by the Cholera for one thing, was enacted. In 1848 the first of many Public Health Acts was passed. Wide ranging in scope the allowed local authorities to undertake works to redress some of the evils of the Victorian urban experience. Housing, sanitation and burials were the three important features of the Acts. The Government allowed local authorities to set up what was known as Local Boards of Health that were regulated by the local authority and the national Board of Health.

One of the first acts of a Local Board of Health was to establish a statutory Burial Board to investigate the purchase of existing cemeteries or to establish their own. In Hull the problems of slum housing and the sanitation of most of the town was addressed first. The issue of providing a municipal cemetery was not a priority because, by the time of the first Public Health Act in 1848, the Hull General Cemetery had been opened. This issue though was to become a running sore between the local authority and the Company during the 1850s and will be the subject of another article later in the year.

Further stories in the press

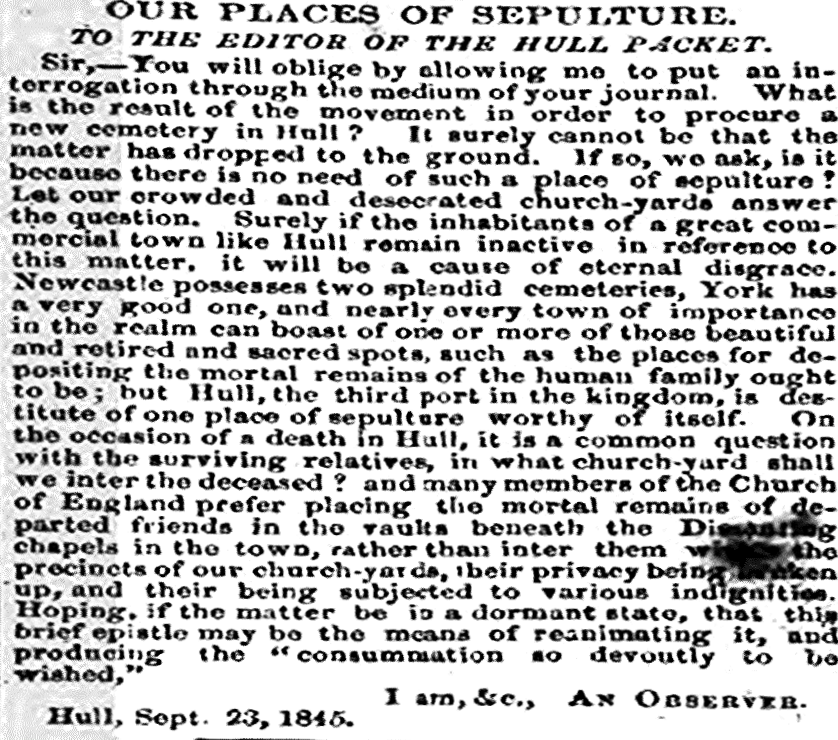

Meanwhile, back in 1843, when hopes were high that legislation would soon arrive to resolve the problem the idea of the cemetery never left the media. Letters to the newspapers increased.

A rather savage correspondent to the local press in February 1843, going by the name “Investigator”, decided to intervene. His reasons for doing so remain unclear. His main brief appeared to be that the burial of the dead within urban centres, especially in the over full church yards in Hull, would be catastrophic to health. He said that it would lead to disease and a rise in mortality to those frequenting those places, and those who were unlucky enough to live near them. In essence, this continued practice, he said, was demeaning to both the dead and the living. He signed off with the message that,

“It degrades religion, brings its ministers into contempt, tends to lower the standard of morality and is a foul blot upon our boasted civilization.”

Cemetery or zoo?

A further correspondent in December 1843 lamented that the Zoological Gardens had been established in Hull when he stated the discussions had been about establishing a cemetery and refurbishing the Botanic Gardens. The writer said he

“gave up his cemetery, accepted the monkeys and the parrots, and concluded to wait for a more favourable opportunity of again bringing forward that which every one must feel the necessity and importance of.”

In the May of 1844, an impassioned correspondent using the title, “Amicus” wrote feelingly of how he had watched a gravedigger in St Mary’s church cut through coffins and human remains to effect a burial in the churchyard there. Of further interest was his comment that,

‘A public cemetery, it is true, was agitated through your columns and, if I am not mistaken, a feeble movement was made in consequence out of doors, but the project appears to have been abandoned; at least I for one have not heard lately that anything is being prosecuted towards securing the accomplishment of so vital a desideratum.’

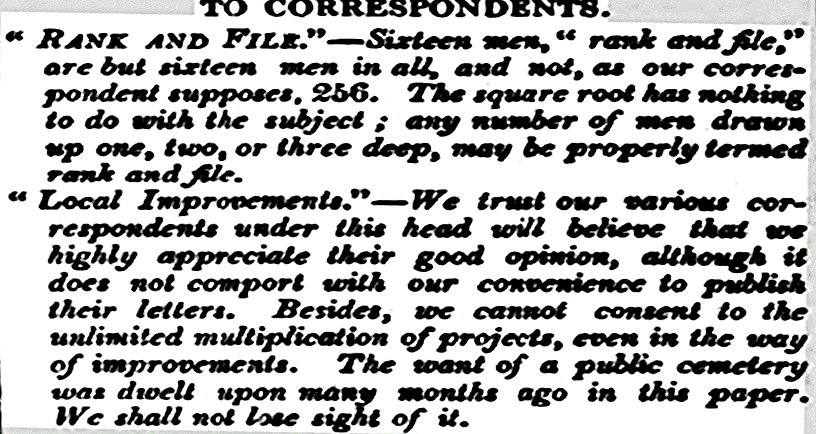

Even the newspapers have had enough

The Hull Advertiser, somewhat curtly, in the October, printed this notice. It was an attempt to hold back the numerous letters it was receiving on the subject.

Likewise, the Hull Packet, one week later, published a scathing editorial of the lack of will and motivation to provide a proper cemetery for the town of Hull. It opened with the statement that,

‘Of the many improvements that are called for in Hull, there is not one so important, or so urgent, as that of its burial places.’

Going on to state, both in an emotional sense and by dry factual evidence, that burying in the old churchyards and burying grounds could no longer continue it argued the case. It concluded thus,

The green shoots of another cemetery company?

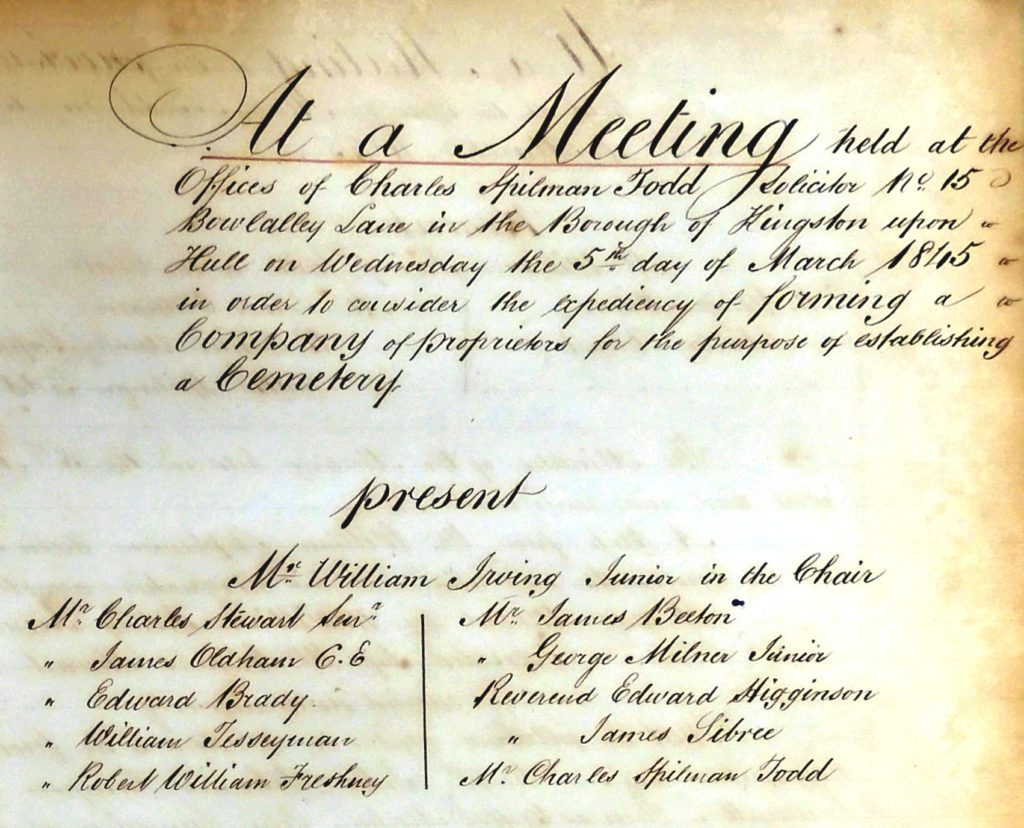

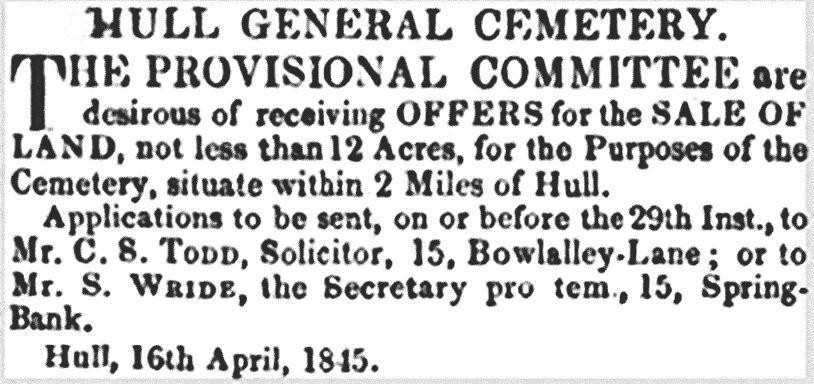

In the January of 1845 a small news item in the Hull Packet said that, “a scheme for a new cemetery had been mooted” but they were not sure of the details. Complicating matters at this time was a proposal from the Dock Company to buy the Castle Street burial ground as it already had adjacent land upon which it intended to build Railway Dock.

This proposal to the churchwardens of Holy Trinity could well have allowed the creation of yet another burial ground under the auspices of the church. And although the churchwardens carried the day, at a very rowdy meeting of parishioners and rate payers, for accepting the offer from the Dock Company, nothing came from this plan.

George Milner

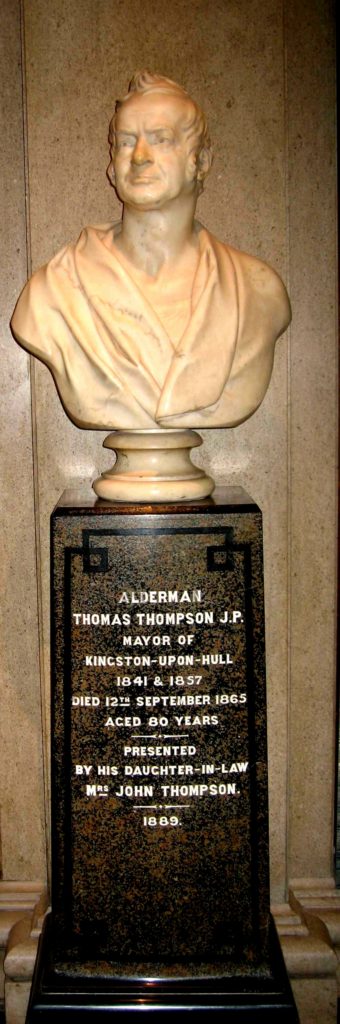

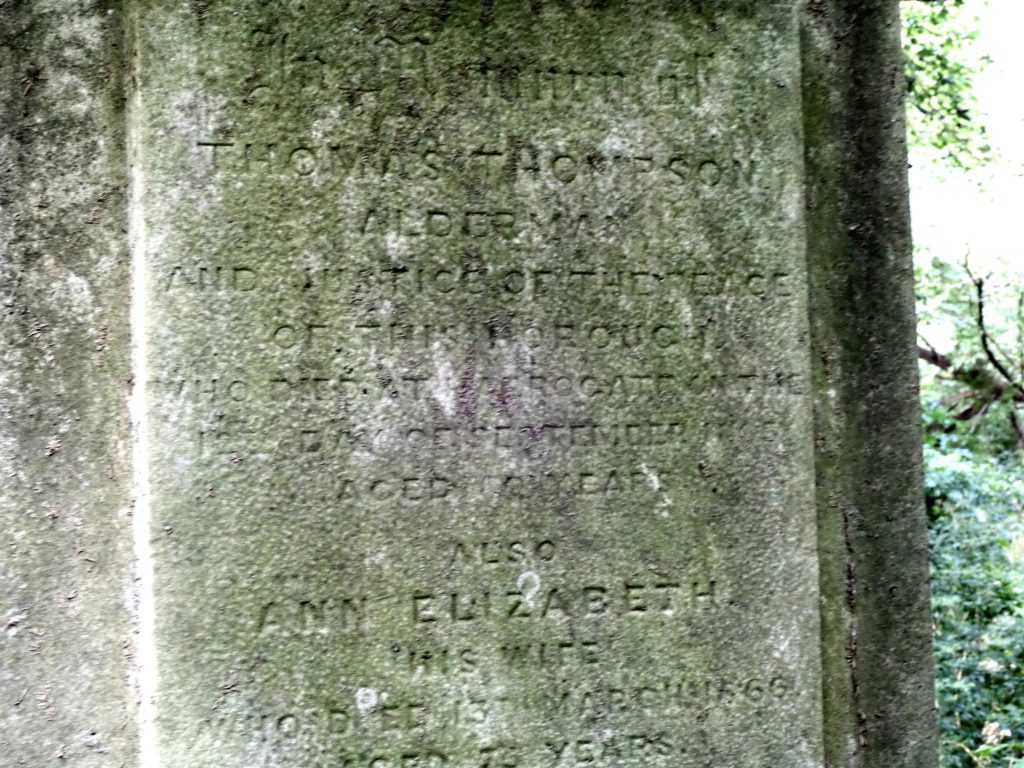

Mr George Milner, was an advocate of cemetery burials. He later became a director of the Cemetery Company, and was buried in there in 1852. His monument still survives as shown below

In February 1845, he was the speaker at a public lecture at the Mechanics Institute. At this meeting he said,

“no town is in greater need of a general cemetery than Hull, and I do hope and trust ere long that one may be formed in every way befitting a town of such importance as our.”

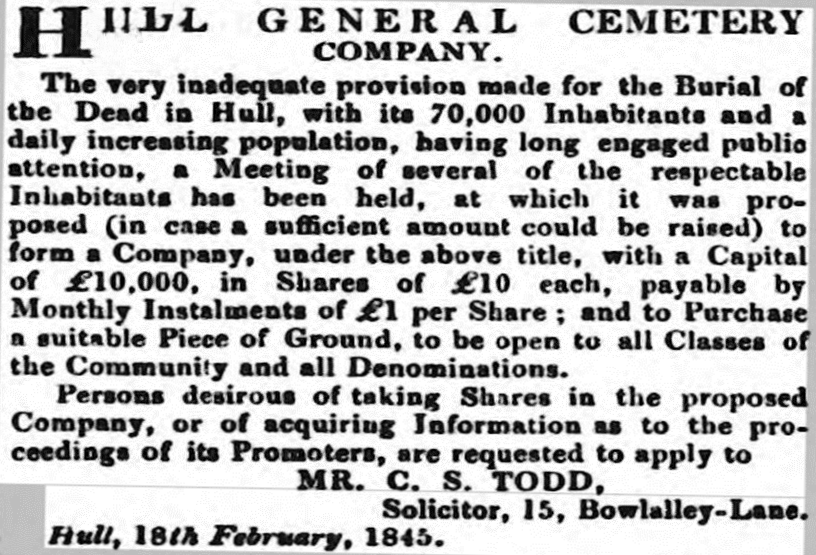

That month the first advertisement relating to the Hull General Cemetery that we have today appeared in the local press.

The ball was finally rolling.

Notes

1. Kensal Green Cemetery is one of the so-called ‘Magnificent Seven’ cemeteries in London. It was the first one to be opened. It was designed as a type known as ‘garden cemeteries’. Hull General Cemetery was of this type. Such cemeteries were given a great boost by the burial of Augustus Frederick, the Duke of Sussex in its grounds. This man was the sixth son of George III. He had been so appalled at the funeral of his brother, William IV, in 1837 he vowed he would not have a state funeral. He was buried – with much pomp – in Kensal Green Cemetery in April 1843. Still later, in June 1848, Princess Sophia, the fifth daughter of George III, also opted for burial in this cemetery. The idea of the public cemetery burial had received the royal approval. Its future was assured.

2. Gatherings from Graveyards was written by George Walker. A thorn in the side to the burial industry notably the church and funeral directors. He cited many instances of sloppy and horrific burial practice which he published in this volume. His work on the charnel house that was Enon Chapel is worth searching out. But only for strong stomachs.

Pete Lowden is a member of the Friends of Hull General Cemetery committee which is committed to reclaiming the cemetery and returning it back to a community resource.