This is the third and final article of the series that is loosely following the same theme. The theme is related to nature, and heritage, the concept of rewilding and the protection of the site. This section deals with the graves, and indeed, the bodies laid to rest in there.

This whole series was prompted by what I saw as the unfair criticism of the work that the volunteers had been doing in HGC. The argument has been made that the work has destroyed habitats of the wildlife in the site.

Hmmm, well, I would suggest that one loss of some habitat for one species is the creation of a habitat for another species. And of course, it’s arguable whether any habitat was destroyed. The work that appears to have ‘destroyed’ this habitat is obviously not of a permanent nature. Anyone who has ever tried to remove blackberry bushes from a garden or an allotment will know too well that they cling to life. The site may look bare but check back in the spring, that will be an entirely different story.

Bodies and graves

Now I would suggest that the natural aspect of the site is important. Unfortunately, it appears to me that perhaps too much emphasis upon this feature is to the detriment of the graves and bodies in there. In my view this approach is to weaken the protection of the site.

Without the presence of the bodies and graves lying within the site, I would argue that every habitat of every creature on the site would have gone a long time ago.

The graves and their inhabitants are often seen as also-rans in terms of importance in the site. Here’s why they are one of the most important reasons why the site was never built on or used in any other way.

Sanctuary

As Charles Laughton would have shouted from the tower of Notre Dame Cathedral in the movie, ‘The Hunchback of Notre Dame’. Surprisingly, the presence of the dead in HGC offers a similar protection to the site from developers. Not a fool proof one as we’ll see later.

Let’s face it, HGC is a good site for development. I can see the brochure now.

“Here’s your chance to buy on the new development of Necropolis Gardens. In the sought after Avenues / Princes Avenue area. Close to a good public school and a good primary Academy.

Excellent public transport links, only 10 minutes from the city centre. Close to the bars and cafes of the Princes Avenue area and a stone’s throw from two large municipal parks and the KCOM stadium.

Come and see the detached show house on Cholera Close and marvel at how we can fit 4 bedrooms (only 2 of which can accommodate a bed) into such a small space. Complete with integral garage.

Pick your own plot soon”.

I think I’m probably under-selling it.

Yes, I am having some fun here but behind it I am deadly serious. It is a good site. It does offer great potential for a serious investor with deep pockets. Especially to a local council who, as reported in the previous posts, has lost 50% of its funding over the last decade. If that investor undertook to take on the necessary legal expenses to ‘develop’ the site, undertook to pay a decent rate for the site, and then proceeded to build ‘executive’ houses on the site, I’m pretty certain that the developer would make a decent profit. The council, for its part, would get a site off their hands that they have no budget for and, apart from some woolly idea about a proposed nature reserve, have no plans for.

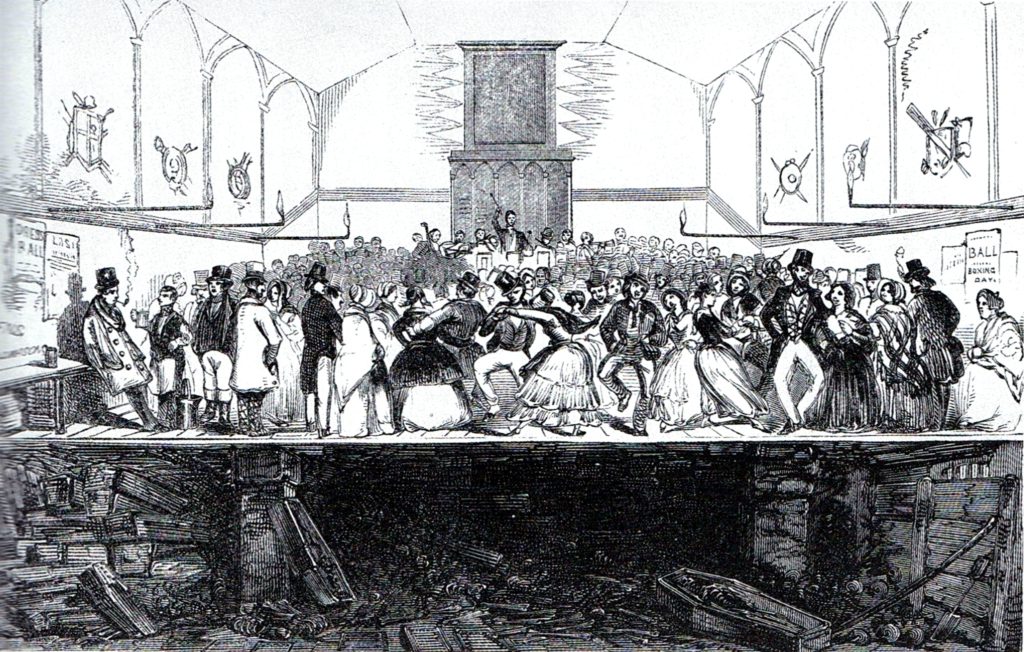

Enon Chapel

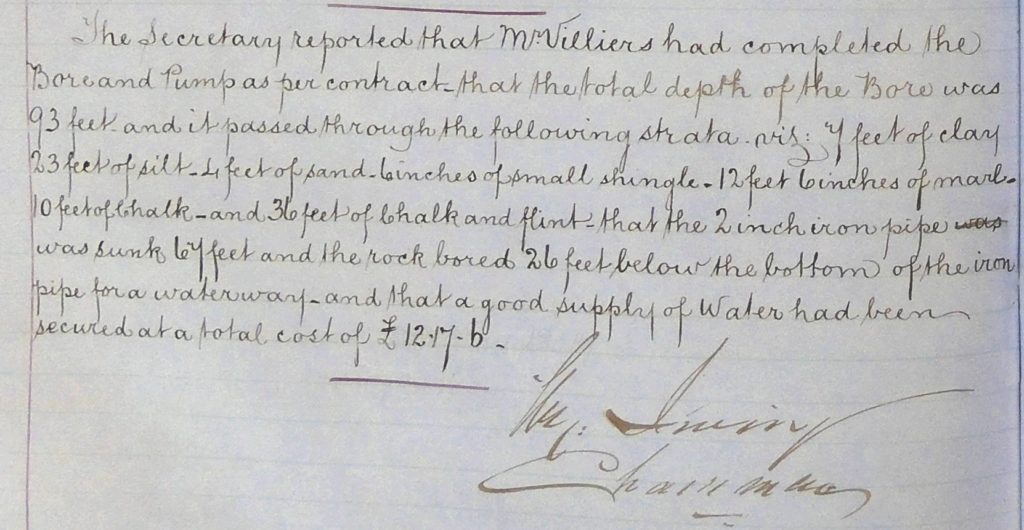

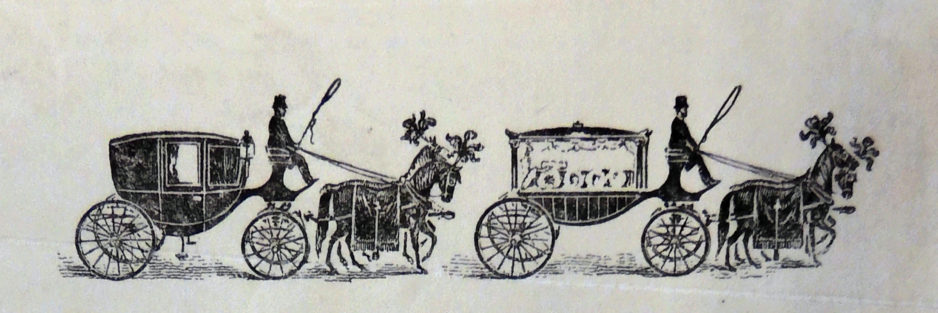

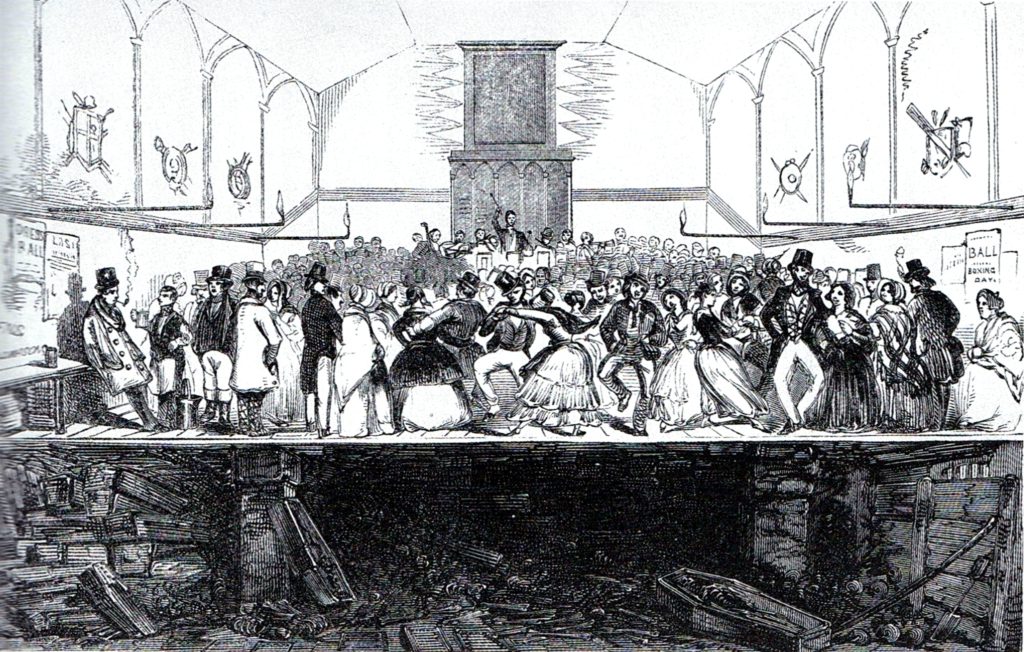

It wouldn’t be the first time that profit has overtaken reverence for the dead. The image above is that of Enon Chapel in London. Notorious for the disposal of the dead entrusted to the minister there. He provided a cheaper burial than the nearby burial grounds and thus attracted considerable customers. He was only caught in this practice because a new sewer was to be dug beneath the building.

As Catherine Arnold, in ‘Necropolis’ recounts, the minister, ‘had succeeded in burying around 12,000 bodies into a space measuring 59 foot by 12 foot’ (1) The depth was 6 foot. Some bodies were removed but the rest were allowed to remain in their basement graves.

The chapel site is now the site of the LSE and when it was being modernised in 1967 skeletons were still being unearthed. The chapel later became a place of pleasure, and dancing parties were organised for a sect of tee-totallers, who rented the property for this purpose. Locally they were known as ‘Dances with the Dead’. A far cry from the way we are led to believe the Victorians revered the sanctity of death.

But back at HGC, as I see it, the major reason these savvy developers haven’t moved in to ‘develop’ HGC is the presence of the dear departed dead. Definitely not because it is a place of natural beauty, home to birds, bats, foxes and other creatures. The presence of such creatures didn’t deter Trump from extending his Scottish golf course on to a site of Special Scientific Interest. The presence of ancient woodland (not the young stuff in HGC) and the creatures living there has not stopped HS2 from bulldozing its way through it.

No, as The Sun (yes, that one) would probably put it, “It’s the bodies that won it”. But let’s not get too carried away.

Progress

There are so many lessons we should heed from our own local history never mind London’s Enon Chapel. The sanctity of burial does not stand in the way of ‘progress’, nor it must be said, has it ever done.

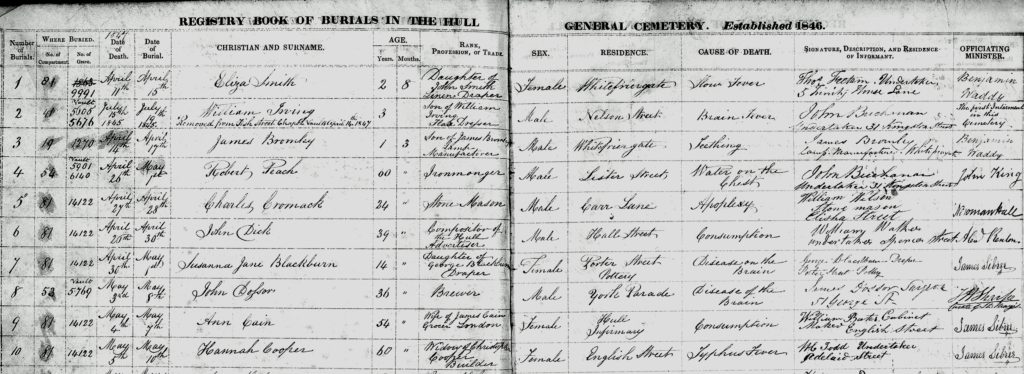

Human remains were found during the digging of the Junction Dock, now Princes Dock, in 1827.

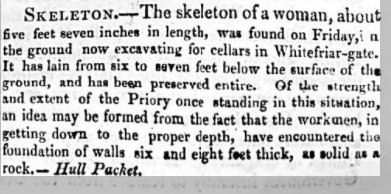

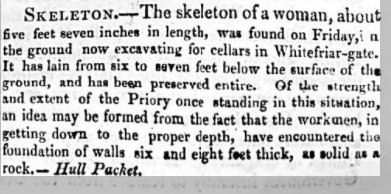

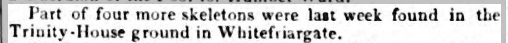

When development work took place in Whitefriargate, at around the same time, the discovery of skeletons did not hinder the completion of the work. The skeletons, presumably buried in what would have been the Carmelite Priory’s burial area that had stood on the site, were simply removed.

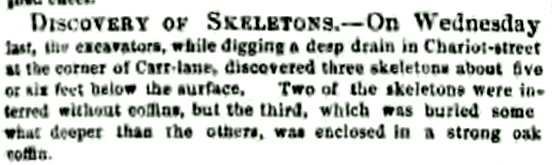

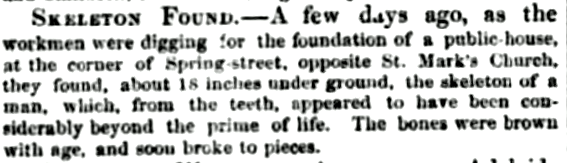

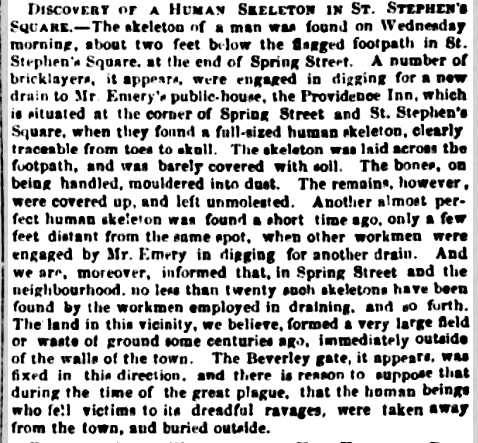

The above extract is taken from The Sun ( no, not that one) of the 7th August 1829. The extract below is from the Hull Packet of the 9th of the same month and year.

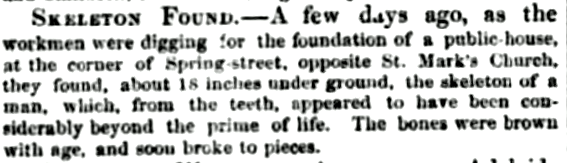

According to the Hull Advertiser, 12 skeletons were eventually unearthed. The skeletons were later reburied in St Charles’ crypt.

There is no evidence that the bodies that were buried in the western half of St Mary’s churchyard, now under Lowgate, were ever relocated when the street was laid out. They may well still be under the tarmac and pavement of this road.

The bodies that were buried in the Augustinian priory, where the Magistrates’ Court now stands, must have been continually disturbed by the building work that took place on that site during the 400 years after the priory’s dissolution. It was known that bodies were buried on this site as one was found there in the 19th century. The Hull Advertiser, in one instance, recorded the discovery of a skeleton under the cellars of the Cross Keys Inn in 1819.

It took until 1974 and work by archaeologists to give the buried of this site some respect and reburial.

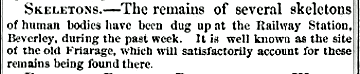

When Beverley Railway Station was being built in 1846 a number of bodies were discovered. It was thought that these too were burials related to the local Friary in Beverley just a little to the south.

Drains and sewers

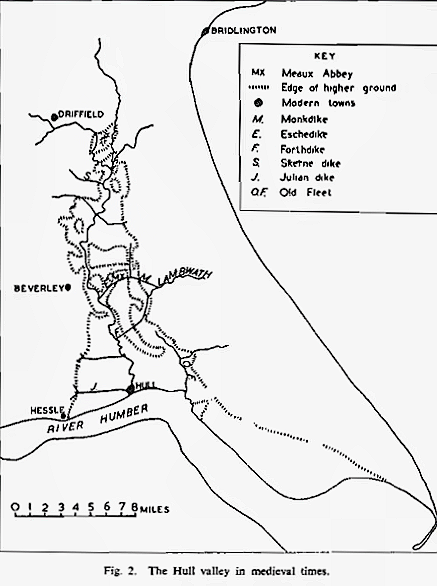

Drainage work appears to have been the major culprit in finding human remains in 19th century Hull as it expanded beyond the old walls.

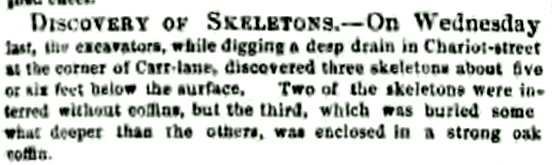

In 1848 at the corner of Chariot Street and Carr Lane a discovery of human remains was made.

A mere 8 months later, in March 1849, a similar discovery in Spring Street was reported.

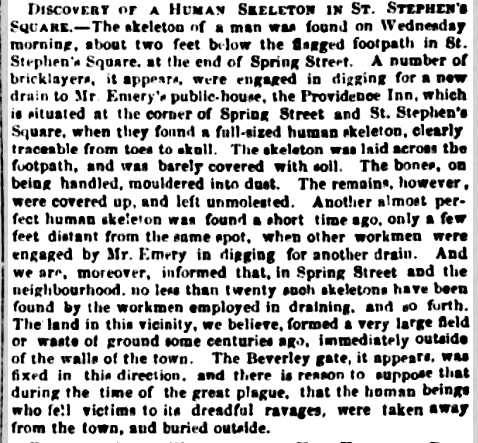

And close by, in the August of 1856, a more interesting discovery took place.

So, taking all of the above into account, I’m pretty sure that non-discovered human remains from the earlier periods of history are pretty common in our area, it’s just knowing where to look ….or not as the case may be. The conclusion that can be drawn from these extracts is that the burials of the past did not stop ‘progress’

More recently

Let’s look at more recent developments.

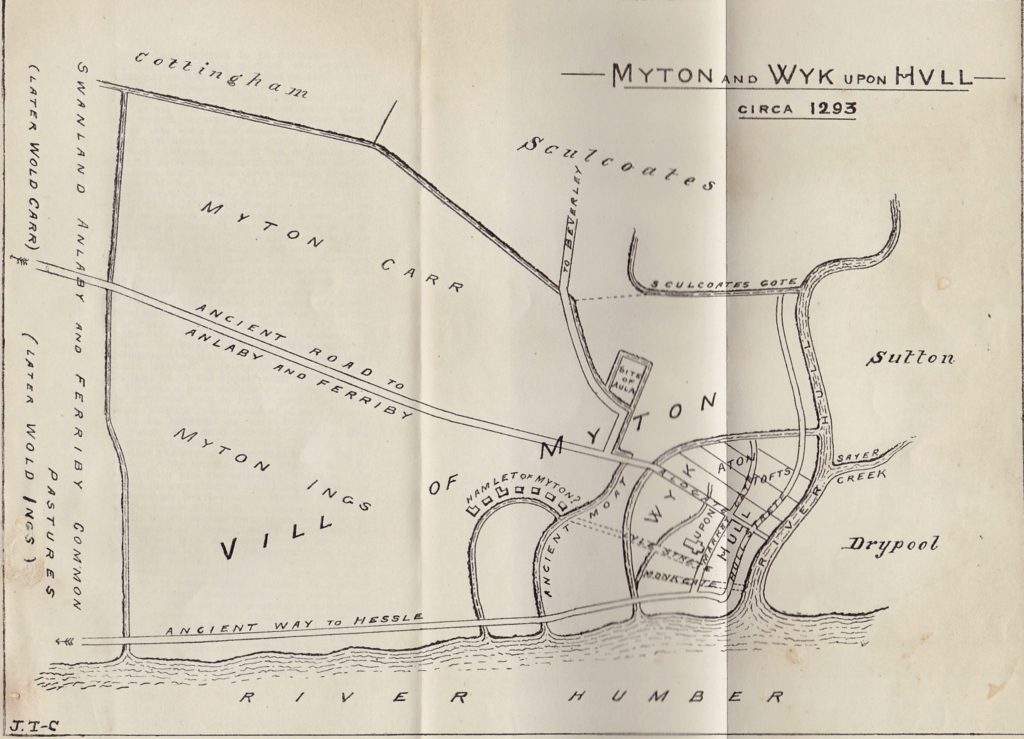

These images are of St Mary’s church yard, or as it’s commonly called now, Air Street cemetery. It is one of the oldest burial places in Hull although it started its life in Sculcoates. It dates back to the mid-13th century. Older than The Minster’s churchyard and also St Mary’s in Lowgate. Its only rival in age is probably St Peter’s, Drypool. Burials have been discontinued here since 1855 although in truth the only burials after 1818 would have been in tombs and vaults already existing.

It’s not great in terms of area, probably about a third of an acre in total. The church that stood on the site was taken down in 1916. The new one was consecrated in the June of that year a little further away, on a site Sculcoates Lane. For a long time the church tower was left standing forlornly until final demolition in the early 1960s.

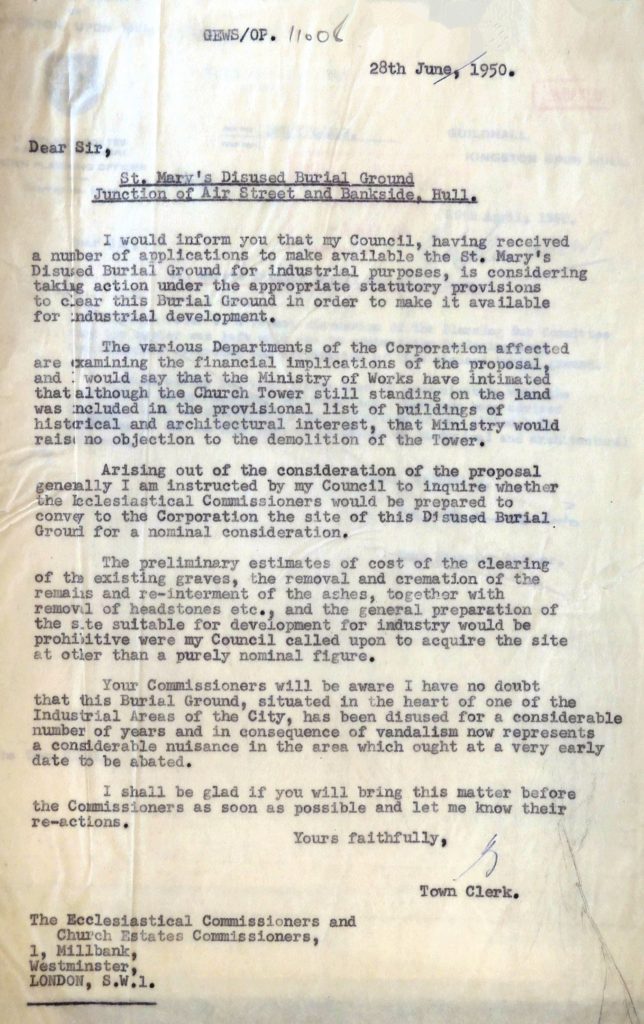

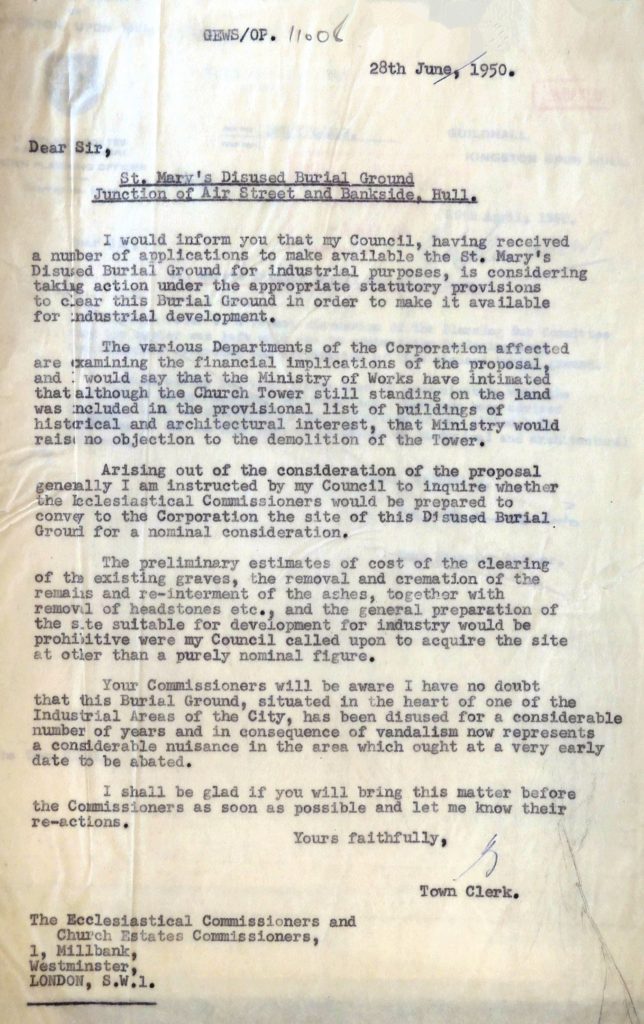

What is not commonly known is that Hull City Council received enquiries about using this site for industrial purposes. The Council, after the war, and obviously wanting to boost local industry, encouraged this interest as can be seen by this letter.

I’m sure you’ll be glad to know that the Church Commissioners and the Diocese of York were opposed to such a move and the scheme went into abeyance. The costs would probably have been prohibitive to the Council at that time. However, if a developer dipped their hands into their pockets in the future….well, who knows?

Earlier this millennium archaeologists were busy again. The churchyard, now known as Trinity Square, which in past times reached as far as King Street, was excavated by the Humberside Archaeology Unit in 2017. There were a number of bodies discovered, complete with coffin remains, most of them from the late 18th century.

It’s interesting, if a little morbid, to think that perhaps the patrons of Bob Carver’s stall were eating their fish and chips over the remains of their ancestors. The churchyard of Holy Trinity was cleared and paved over in the 1840s but obviously the clearance was not very thorough.

Bodies were also found during the development of the St Stephen’s Centre. These were the remains that had failed to be removed when the St Stephen’s churchyard was cleared after the bombed church was removed in 1960.

And how can anyone fail to notice that the Castle Street cemetery is suffering a truncation, which includes the removal of human remains? Evidence surely that the presence of human bodies does not give complete protection to sites when there is deemed to be a need for change. Or do I mean ‘progress’?

HGC is safe though, isn’t it?

I’d like to think so. After all it is in a conservation area. Strangely, so is Castle Street cemetery. Am I just splitting hairs by putting that in?

Hymers College is in the same conservation area that HGC is in, yet there has been a plethora of new buildings erected in its grounds since the conservation area status was granted. Yes, I’m sure, in this case, that everything is above board and the Council granted permission for this work. The point I’m making is that Conservation Area status does not exclude changes that the site owner deems necessary.

A conservation area does not confer immunity either. In much the same way that having a building or structure ‘listed’ does not stop it from being destroyed. We’ve all seen examples where some building was listed with one or other of the various bodies that supposedly care for such things. Then, whoops, it has ‘inadvertently’ been reduced to rubble. To paraphrase myself from an earlier article, ‘nothing lasts, change is constant.’

In other words, nothing is really certain about the future of the HGC. Let me give you an example.

Dual carriageway

Back in 1977 we bought our first house. It was a small terraced house in Mayfield Street, just off Spring Bank. We had some difficulties in buying it. This was due to the fact that when our solicitor did some searches on the property it was deemed to be at risk of demolition. This demolition was going to take place because an orbital road was planned. A dual carriageway was proposed, running along the old Hornsea railway line until it reached Wincolmlee. This road would have demolished most of Louis Street, Middleton Street and Mayfield Street. The top of Mayfield Street is to the left of the photograph below.

At the other end it would have joined onto Spring Bank West leading up towards the railway line crossing. This stretch would have been ‘upgraded’. This upgrade would have been transforming the road as it is into a dual carriageway. Now how could that happen?

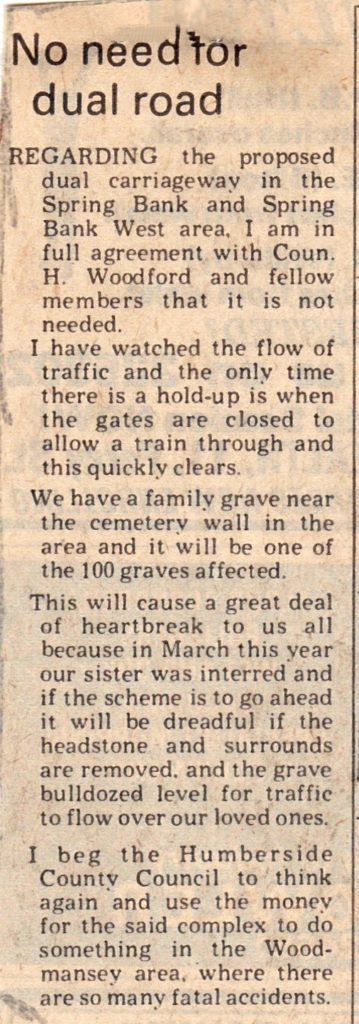

Simple, the plan was that a part of both of the cemeteries, HGC and Western, would have been taken for this road widening. As one letter writer to the Hull Daily Mail put it,

By late 1979, this idea had been shelved. But this doesn’t mean that this idea cannot ever be resurrected. If someone, say Highways England, came up with the money, as they did with the Castle Street development, who can say what would happen?

Council dual purpose in clearing headstones?

The other issue that needs to be borne in mind here is that the idea was actually brought to the then Humberside County Council and they deliberated on it. This was a definite project. Surveys were made, budgets were calculated. This project would have taken all of the pavement and at least another 50 yard strip of both cemeteries from the railway crossing to Princes Avenue corner. This plan would not only widen the road but would then have to replace the pavement further back. I’m not even taking into account the excavation work for the sewerage, gulleys and drainage.

What a dismal prospect. It was discussed, debated and voted upon by Humberside County Council. What is hopefully coincidental is that this proposal occurred whilst Hull City Council were ‘developing’ HGC. Strangely almost all of the headstones that once stood close to the road were removed in the clearance. That would have been extremely helpful if the road widening took place. Yes, I’m sure it was a coincidence but sometimes you do have to wonder.

Firstly; the woodland

So, now I come to the grist of these articles. I’ve come to believe that HGC is precious. In essence it is a one-off in Hull in two ways.

Firstly, it is the closest one can get to a woodland in an urban setting. Unplanned by humans for the last 40 years it has happened as nature intended. Nature abhors a vacuum as they say. This isn’t to say that nature doesn’t need a helping hand.

Left to its own devices the site would be a wilderness with no place for humans. And by that I mean that humans would not be able to enter it after a while. The paths would be impassable. The blackberry thickets would grow bigger every passing day, the rubbish would accumulate just as if by osmosis.

No, not a pretty sight. I believe that all such areas need managing. There are no areas of countryside that are not managed to a greater or lesser degree to meet the needs of the owner, consumer or visitor. And this management also assists the site and its wildlife inhabitants.

I’m pretty concerned when I hear people arguing against management of HGC. I’m sorry but we’ve seen where over 10 years of the policy of ‘managed neglect’ delivered HGC. A haunt for drug users, alcoholics and rough sleepers. A sex playground / brothel, rubbish dump and sometimes, sadly, a serious crime scene. When people talk about ‘wildlife’ I’m pretty certain they don’t mean that kind of wildlife. So management is key.

Secondly; the heritage

Secondly, it is the only private cemetery that ever existed in Hull. On that basis alone it is precious and irreplaceable. It is the last resting place of numerous Victorian and Edwardian people who died and were laid to rest in there. It is a vivid representation of the social class structures that prevailed in Victorian society The class divisions of that society are frozen in time and made more tangible to us than any textbook could ever do. Those divisions are laid bare by such things as the burial area for the workhouse inhabitants and the massive monuments to the more privileged inhabitants. But this heritage needs as much protection as the nature in there.

Below is a photograph of some headstones in HGC completely covered in ivy, which is systematically destroying them.

Here’s a headstone with the ivy removed and showing the damage done to the stone.

Some of the people buried in there wanted to be remembered, or perhaps their relatives wanted to memorialise them. In doing so they had erected some beautiful sculptures. Those sculptures are irreplaceable. More irreplaceable than blackberry bushes and sycamore saplings.

They are, like the cemetery itself, original and special, and as such also need our support. In fact they need it just as much as the wildlife.

A middle way

Taking all of the above into account, I would suggest that a middle course is the way forward. A way that does not put forward the claim that nature is more important than the heritage or vice versa. Both strands and elements of HGC are vital to each other’s self interest. Together the arguments against the site ever being lost to development are that much stronger combining nature and heritage. It really is a case of united we stand, divided we fall.

So perhaps, on this point, we should place the work of the FOHGC in context. The FOHGC attempts to take on board both of the two elements mentioned above, and works to accommodate both of them. It doesn’t favour one or other. It takes the hard road and seeks a balance between nature and heritage.

Try to remember that when you want to have a little moan about something that offends you. It just might be something that offends some of the people of the FOHGC but that’s the way it goes. The FOHGC have to try to get the balance between nature and heritage right. No one said getting that particular balance right is easy. No, what’s easy is criticising; the hard part is trying to do something positive.

- Catherine Arnold, Necropolis. Simon and Schuster, 2006. I do recommend this book as a good overview of burial through the ages. It obviously has a tendency to look at London more than anywhere else.

- It would be immodest of me to mention that A Short History of Burial in Kingston Upon Hull from the Medieval to the Late Victorian Period by Lowden and Longbone deals with the subject more locally. Sadly out of print but copies are in the Hull History Centre.

Pete Lowden is a member of the Friends of Hull General Cemetery committee which is committed to reclaiming the cemetery and returning it back to a community resource.