The catacombs of Hull General Cemetery are now long gone. Nothing remains of them. (see the link below)

Unlike the Eleanor Crosses. Let us examine their history here.

Thompson and Stather

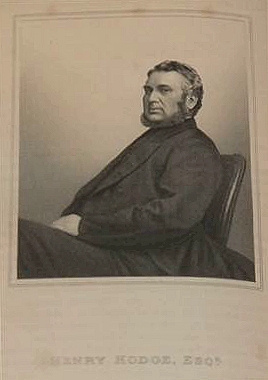

We’re fortunate in having a reasonable idea of who built the crosses. The firm of Thompson and Stather were an engineering firm in Victorian Hull. This firm had a long relationship with the Cemetery in its early days. The Stather in this firm was Thomas Stather. His brother John was equally as successful in his business enterprise. Their stories will be published on the website at a later date. Suffice to say here that, in terms of Hull General Cemetery, both brothers and their families are buried there.

As an example of Thompson and Stather’s relationship with the Cemetery Company, in August 1852 the firm were approached by the Company. They were asked to make some new gates for the Cemetery. These listed gates still survive and may be seen on Spring Bank West. They also completed a number of other contracts for the Company. Thompson and Stather were one of the foremost engineering firms of the Victorian Hull. So it stands to reason that the Cemetery Company would have dealings with them.

Family tragedy

In 1863, Thomas Stather’s wife, Elizabeth, died. She is buried in the Cemetery. The grave is a brick lined vault. Luckily it still has the headstone. Or should I say it has a large Eleanor cross on a plinth erected upon a sandstone kerb set. The cross is made of cast iron. It was the first one erected in the Cemetery and was made by her husband’s firm of Thompson and Stather.[1]

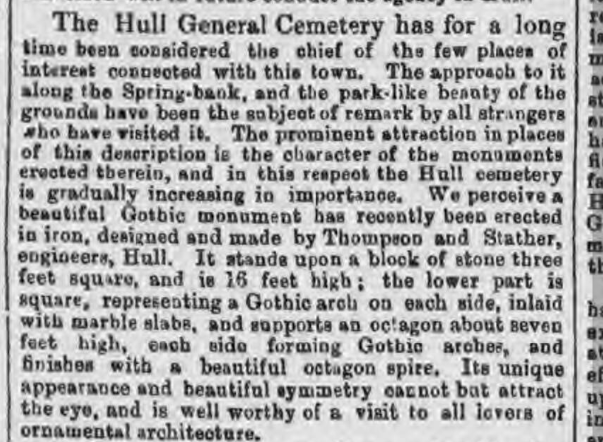

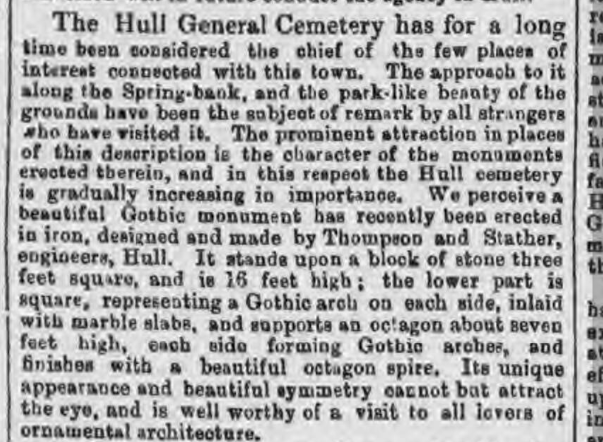

How do we know this? Local resources are scarce on these matters. We do have a newspaper report that quite clearly speaks of the erection of the cross in the cemetery. This newspaper report is shown below.[2] Thomas Stather’s wife of over 25 years, Elizabeth, died on the 1st April 1863. On the 11th September that year the cross had been erected on the grave where Elizabeth lay. I would suggest this is as concrete a proof as one may wish for.

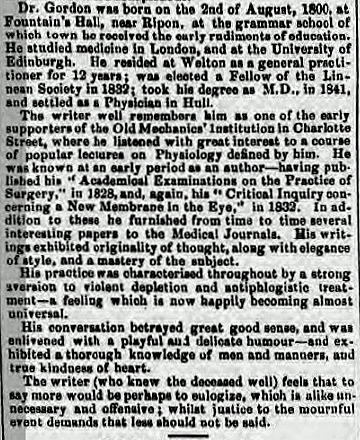

Fig 1: 11th September 1863, Hull Packet.

Fig 2: Thomas Stather’s grave. The site of the first Eleanor Cross erected in Hull General Cemetery

The second Eleanor Cross

The second Eleanor Cross is situated about 50 yards west of the main gates of the Cemetery. It celebrates the grave of the Mason family. The plot was initially bought by Benjamin Burnett Mason. He was born on 16 Feb 1822 in Hull. The son of master mariner Samuel and Martha Mason (nee Green), he was baptised at Holy Trinity on the 9th April 1822.

Benjamin married Anne Green on 19th June 1844 and they had 2 sons, Benjamin William, born in 1846, and Samuel Burnett born in 1850. In the 1851 census Benjamin and his family were living at Northgate in Cottingham and he is listed as a wine merchant and ship owner. He was successful in his business enterprises and established a large wine and spirit business in Lowgate. Its premises eventually extended close to the quays of the Queen’s Dock, now the site of Queen’s Gardens. He also was successful in the community. He became a JP and a Guardian of the Poor. Not content with that he turned his hand to history and was the author of a book entitled The Brief History of The Dock Company. Throughout his life was also an active member at the Minerva Lodge of Freemasons.

The move to Hull

The family moved from Cottingham to a new home at 3, Grosvenor Terrace on the Beverley Road, which is now numbered 113 Beverley Rd. A grand address in its day. It was then on the outskirts of Hull and was situated just outside the village of Stepney.

However, like all Victorian families whatever their circumstances, tragedy was never far away. On the 2nd December 1863, the eldest son, Benjamin William died at the family home from scarlet fever. He was only 18 years old. It is believed that this is when the second elaborate cast iron ‘Eleanor Cross’ was erected in Hull General Cemetery. This would have been some three months after the first cross was mentioned in the press.

There is no record in the newspapers of this new cross being erected. Nor any record in the Company’s minute books or any other documentation to confirm this. However, it appears to fit the bare facts as outlined above.

When was it erected?

We know the original cross was erected in or before the September of that year. The death of Benjamin William Mason took place in December. During the consequent sorrow that almost certainly gripped the family, it is conceivable that the family seized upon making a significant gesture to mark the passing of their son. I would suggest that they commissioned the cross on their family tomb at this time. The erection of this cross was probably appropriate and timely. Grief was something that the Victorians often felt needed to be reflected in ostentatious display and the erection of this cross certainly does do that.

Fig 3: The site of the family home on Beverley Road, 2018. Just out of the picture to the left is ‘Welly Club’.

Benjamin’s wife, Anne, was buried in the family grave, dying from bronchitis on the 7th February in 1874 aged 57. Benjamin’s younger son, Samuel, eventually joined the family company, and continued to work in the business.

Benjamin died of bronchitis on the 12th January 1888 aged 65. Samuel died in Cairo, Egypt on 19th Jan 1894 and was buried there. Samuel’s widow, Mary Ellen, was buried as cremated remains in the family tomb, the final interment under this Eleanor Cross.

Fig 4: Mason’s Eleanor Cross.

The saddest story of all?

The final Eleanor Cross is perhaps the most poignant story of all. It is the smallest of the three crosses and it stands on top of a grave dug for just one person. Yet it is a public grave. A strange occurrence and the only instance known in Hull General Cemetery. As the reader knows, public graves rarely have any kind of memorial upon them. To have a cast iron monument on it is unheard of. Let’s examine the facts of the story.

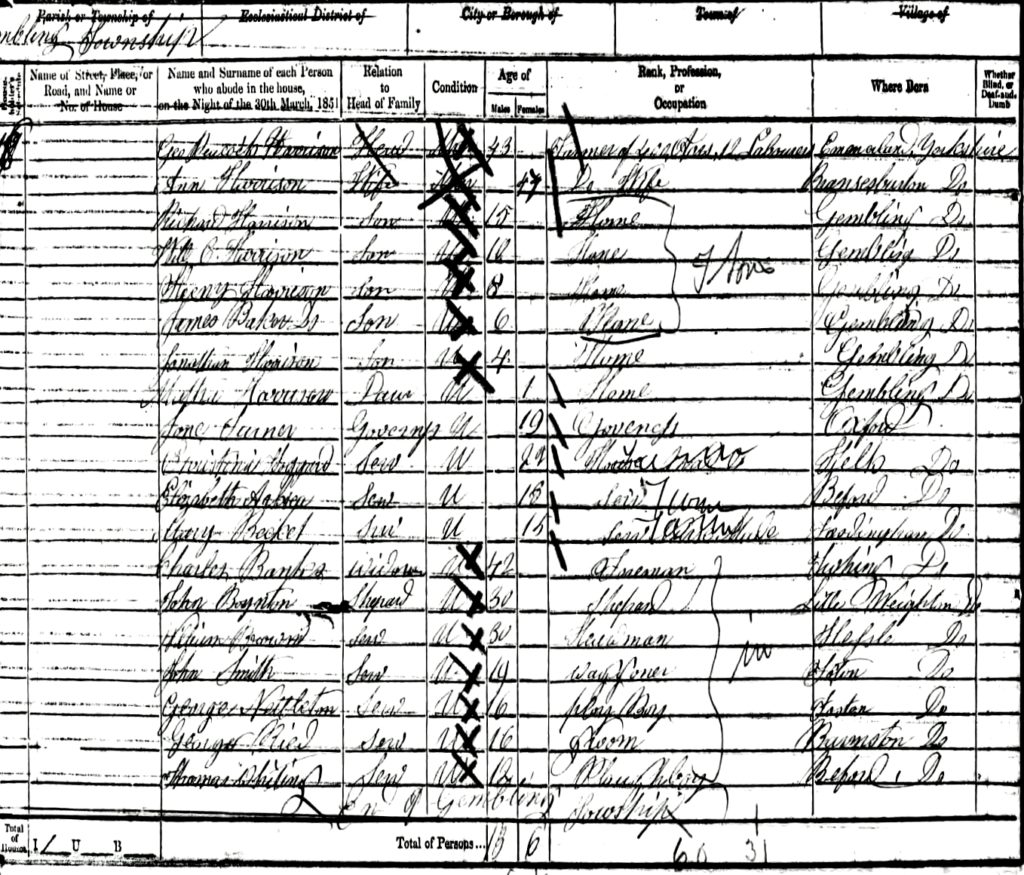

We need to go back in time a little to fully explain the Crosses’ story. In the East Riding a farmer by the name of George Peacock Harrison, 1808-1885, and his wife Ann, 1807-1872, lived in the village of Gembling, near Driffield. He farmed approximately 400 acres and employed over a dozen farm workers, so he was an influential man in that neighbourhood. Throughout their married lives, he and his wife had eight children. The two we need to focus on are his third child and second son, George Peacock, 1839-1916, and his seventh child and sixth son, Jonathan, 1846-1887.

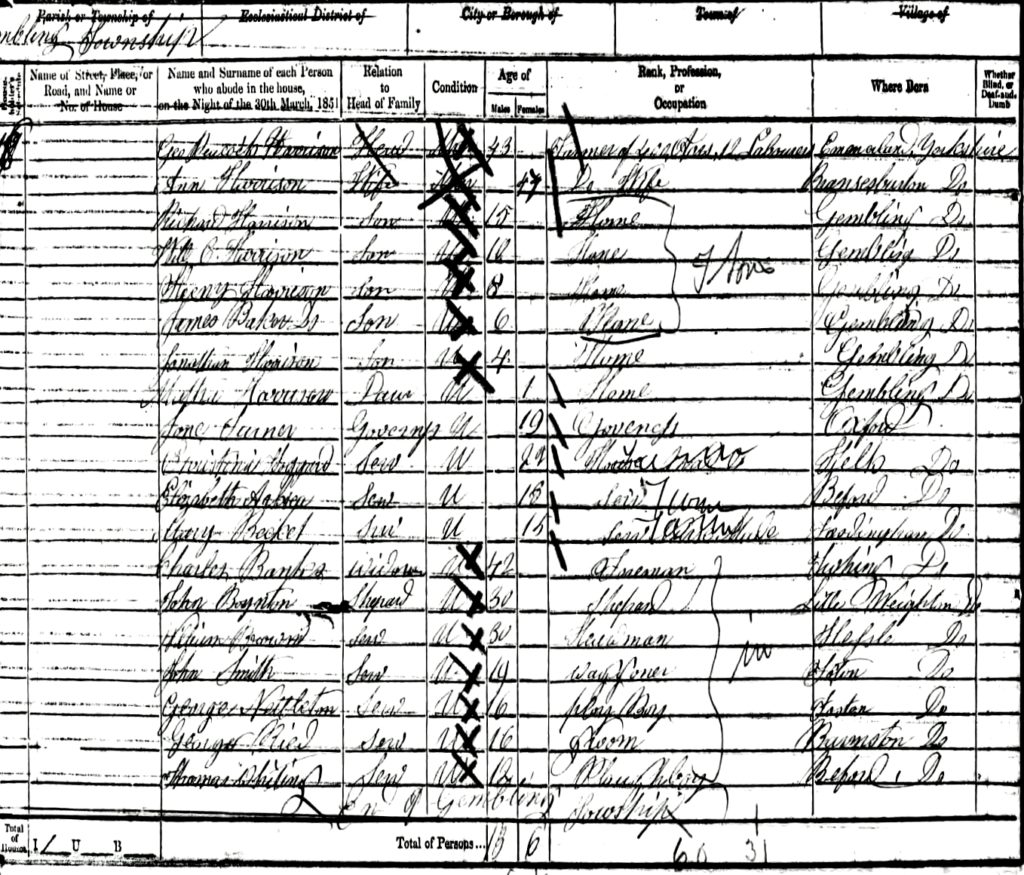

The 1851 census

As can be seen in Fig 21, G.P. Harrison’s family is gathered around him. Jonathan being four years old, but there is no sign of George Peacock junior. This was because he was absent at school in Hampshire. There is no record of any other of the children being so favoured.

By the 1861 census, George Peacock senior and his wife have moved to another farm at Wharram of 1000 acres. Their two daughters and William Christopher, the third son, went with them. His previous holding was now being run by his son George Peacock junior. No other family member resides at this time at the Gembling farm.

A George Peacock Harrison had appeared at the Assizes on a charge of rape but, according to the Barnsley Chronicle of 15th December 1858, the Grand Jury, ‘ignored the Bill’ and he was allowed to go free. We have no way of knowing which George Peacock this was but the offence was against a woman in Wharram, so it may well have been George Peacock senior who was in the dock.

Fig 5: 1851 Census record for George Peacock Harrison and family.

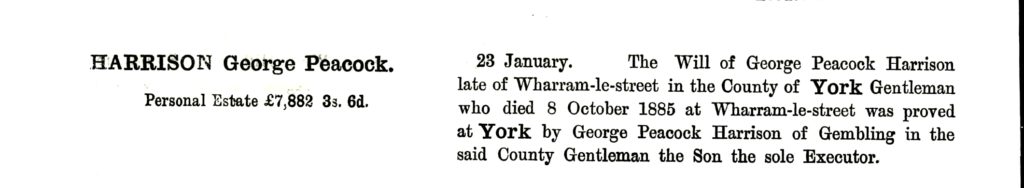

The death of George Peacock senior

The younger George Peacock was unmarried. This personal situation continues through the 1871 and 1881 censuses and his father continues to work the Wharram farm. In October 1885 George Peacock senior died.

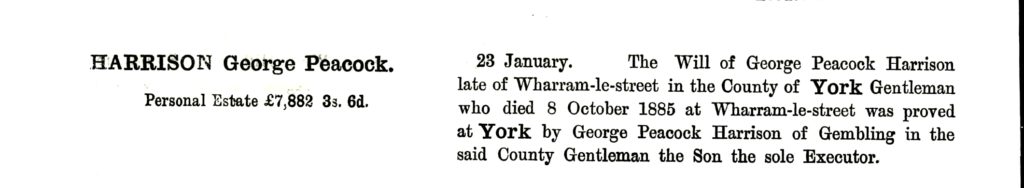

Fig 6: Probate of G.P Harrison senior.

As the sole executor George Peacock Harrison junior could administer his father’s estate as he chose and this is what he proceeded to do.

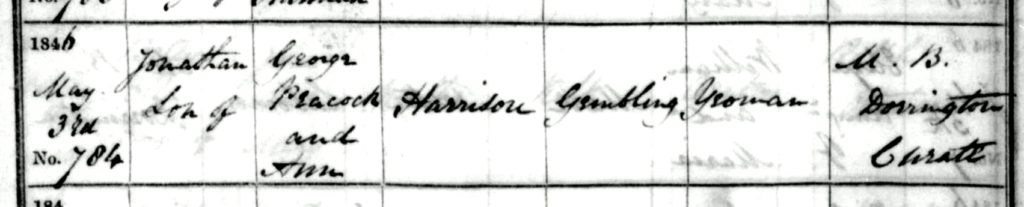

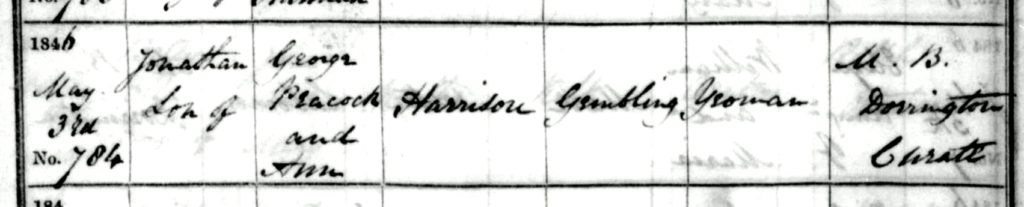

Let’s just take a look back at Jonathan. He was born in 1846 and baptized that same year in the local church.

Fig 7: Jonathan Harrison’s baptismal record, May 1846.

Other than the entry on the 1851 census we lose track of Jonathan. He doesn’t surface in any of the censuses of 1861,71 or 81. Yes, there are characters who could conceivable be him but they are far removed from the family settings.

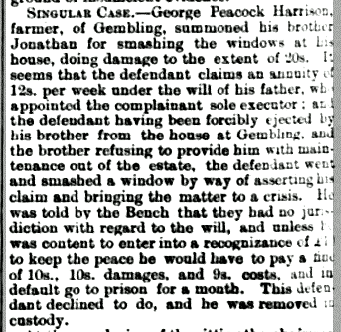

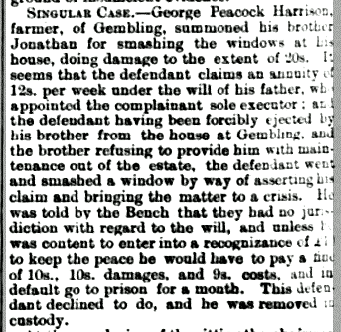

In the dock

The next we hear of Jonathan is in a court case. Reported in the Driffield Times in the July 1887. As can be seen in below, Jonathan appears to have had an altercation with his brother George Peacock Harrison junior. During this altercation he committed criminal damage to his brother’s house. The problem appeared to revolve around the will of their father, and money that Jonathan thought was his due. Being legally summoned by his brother must have been difficult for both sides. It was further exacerbated by Jonathan refusing, or being unable, to pay the fine. This resulted in a custodial sentence of one month for him.

The final straw

This appears to have been the final straw for Jonathan. He obviously removed himself to Hull for the next and final part of this sad story. We find Jonathan next having died aged just 40. Only four months after his release from prison.

Fig 8: 2nd July 1887, Driffield Times report of Jonathan’s offending.

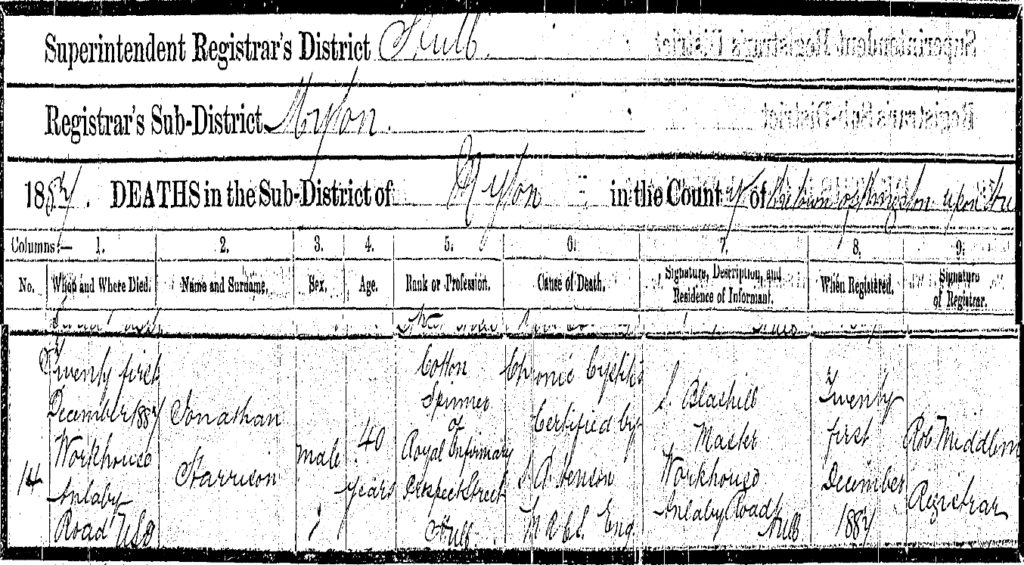

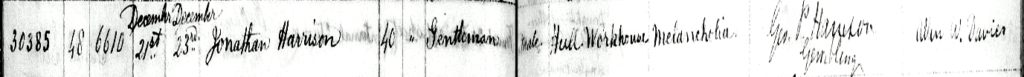

Jonathan’s death

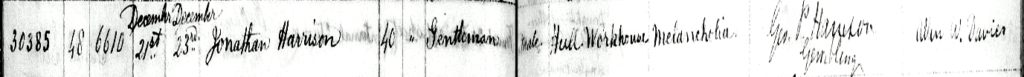

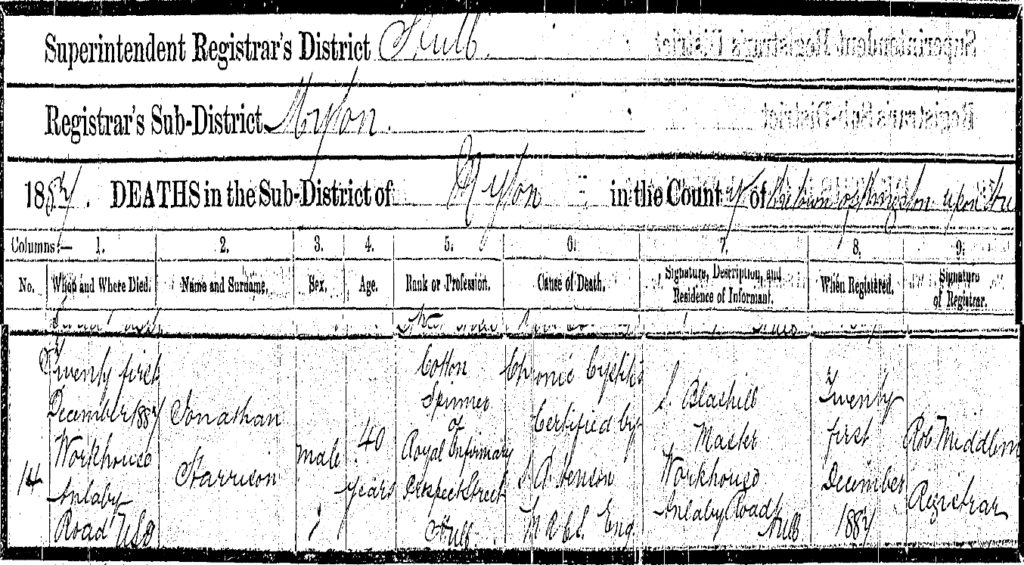

Fig 9: Jonathan Harrison’s Death Certificate.

Jonathan died four days before Christmas Day 1887 and of Cystitis which was a disease that he could easily have contracted whilst in prison. As can be seen, he was earning his living as a cotton spinner at the time of his death and his place of work was the Royal Infirmary in Prospect Street. This was work that he would have been detailed to do as his place of residence was the Hull Workhouse. He would have been an out-worker for that institution, paying for his placement and meals by this form of work. He would, therefore, have been accorded a pauper grave.

The final gesture

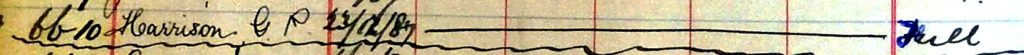

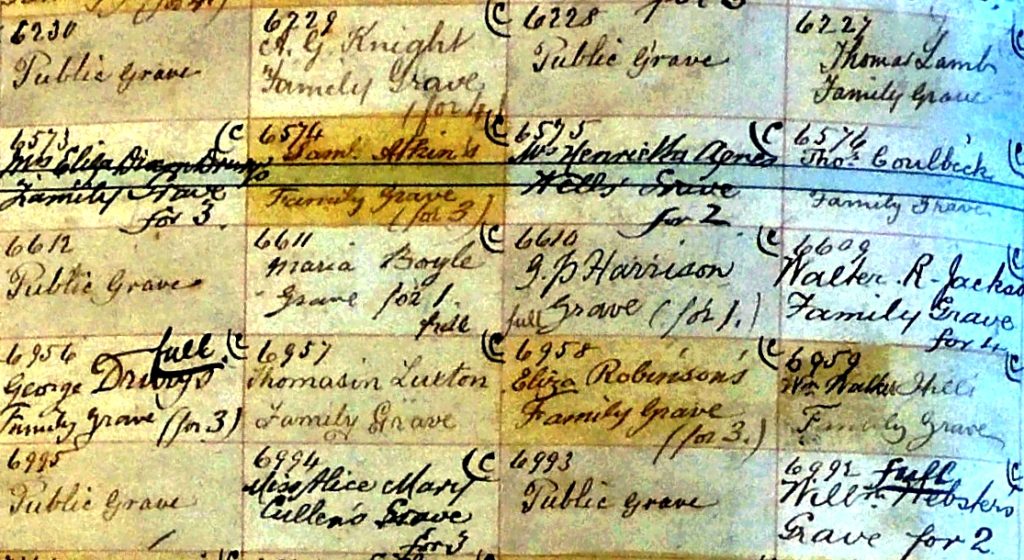

Jonathan, surprisingly, lies in a grave that was purchased for one burial. Exceptional and unique for a public grave. The purchaser was a certain George Peacock Harrison. Jonathan was buried on the 23rd December 1887. The rest is conjecture. Was this purchase by George a belated gesture to his dead brother? Had he done his brother wrong? We don’t know. What we do know is that after the burial and the purchase of the private grave for one person only, the grave was surmounted by an iron Eleanor cross.

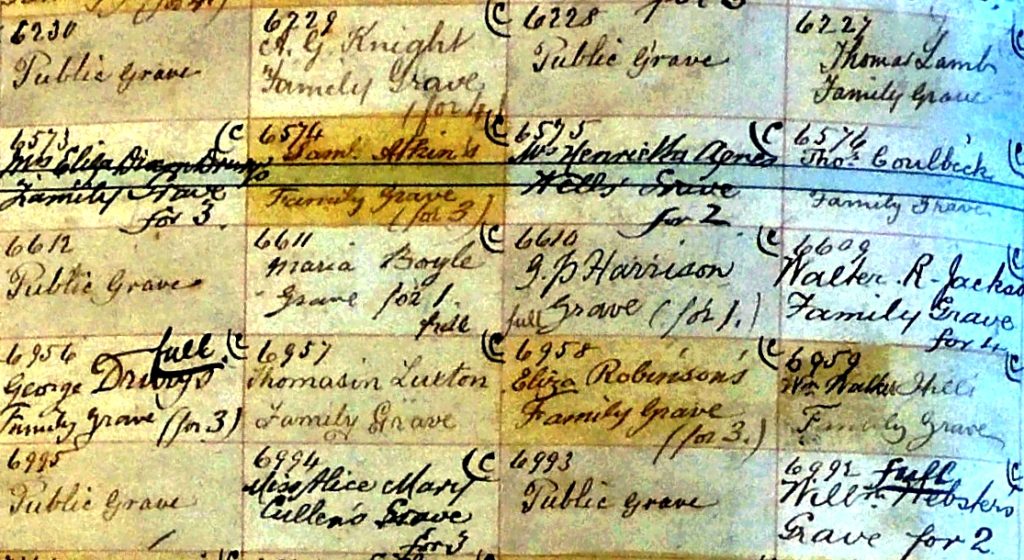

Fig 10: Grave space of Jonathan Harrison, purchased by G.P. Harrison. It is the third row from the left, fourth space down. No. 6610, Compartment 48.

Not by Thompson and Stather

A smaller version and less detailed than the Thompson and Stather ones true, but a good monument. Thompson and Stather were both dead by this time and the firm dissolved. George would have probably ordered a similar cross for his brother from someone who said they could do the job.

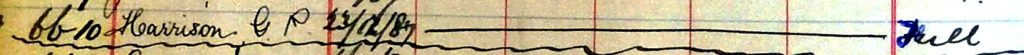

Fig 11: Grave number and the purchaser’s name, how many burials and for how many. In this case there is one burial and the grave is stated to be full.

The purchase of the iron monument appears to go beyond grief, and perhaps touches upon a deeper remorse, maybe even fuelled by guilt. We shall never know. George Peacock Harrison continued working the farm at Gembling but in the early part of the 20th century he emigrated and spent his remaining years in New Zealand. He died at Cartertown on the 9th March 1916. We don’t know what was going on in George’s mind. We can only guess. My guess is that this purchase of Eleanor Cross is due to remorse. The only indication of this may be found in the burial register of the Cemetery where he was listed as the informant,

Fig 12: Hull General Cemetery burial register, December 1887.

Melancholia or remorse?

As you can see, George Peacock Harrison cites his brother as being a ‘gentleman’ and his cause of death as ‘melancholia’. Hardly a cause of death then as now. Much more probably a symptom of how George was feeling at registering his brother’s death with the Cemetery, and at the same time purchasing the burial plot for his younger brother. The brother whom he had taken to court. who had gone to prison as a result of these court proceedings. The brother who eventually ended up in the workhouse where he died.

Yes, I would think there was a lot of melancholia, but I think it was George who was suffering from that, rather than Jonathan.

And that is the end of this short journey examining the Eleanor crosses of Hull General Cemetery.

Fig 13: Jonathan Harrison’s grave with its monument.

Acknowledgements:

Fig 1: Hull Packet.

Figs 2, 3, 4, 13: Authors’ collection.

Figs 5, 6, 7: The National Archives.

Fig 8: Driffield Times.

Fig 9: General Record Office.

Figs 10, 11, 12: Hull History Centre.

The Catacombs of Hull General Cemetery

[1] Not Young and Pool as Historic England maintain on their website for Hull General Cemetery.

[2] See Fig 1.

Pete Lowden is a member of the Friends of Hull General Cemetery committee which is committed to reclaiming the cemetery and returning it back to a community resource.