This month the anniversary we are celebrating is an unusual one It took place in July 1880.

One of the problems that Hull General Cemetery faced, and surprisingly is still facing, is access to water. Not the rising water that you’d expect from a cemetery built alongside two drains. No, the problem was, and is, the difficulty in obtaining fresh water.

There was a well built when the Cemetery opened. This was in the work yard to the north east of the site. This was used by the workforce for watering the Cemetery horse, cleaning the stables, cutting the stonework and other tasks.

What a bore!

However there was nowhere for patrons of the cemetery to replenish their water for their flowers. After numerous complaints the Board decided to do something about this.

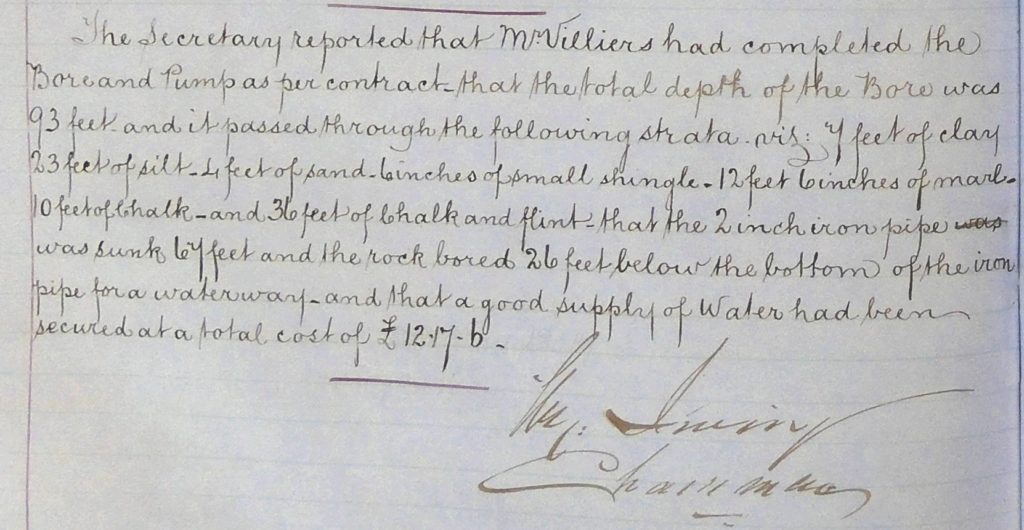

In June 1880 they asked a Mr Villiers, a surveyor, to construct a bore hole in the cemetery. A price was fixed of around £12 for this task and on the 1st July 1880 Mr Villiers set to.

The bore hole passed through many layers, as the Minute Books tell us, and finally reached a fresh water spring.

So the borehole was 93 feet deep. The strata that this bore passed through is very interesting. It probably shows the way most of the geology of the Hull Valley is comprised. Clay, chalk, marl and flint. At some point it was a sea bed. A sea bed from million of years ago. I still have the proof.

When I worked in the Cemetery, when it was much less overgrown, it was possible to pick up Gryphaea arcuata by the handful. Known commonly as Devil’s Toenails, they are a fossilised mollusc or type of ancient oyster.

They lived mainly during the Triassic and Jurassic period. Approximately they lived 200 million years ago. I was always surprised that these fossils were so abundant. And also, only in Hull General. I never found any in Western Cemetery next door. What was going on?

Jurassic Park

I now believe that I have solved that mystery. I think that they were abundant because they had been returned to the surface from the depths they had been buried in over those millions of years. By the drilling of this bore hole the debris from it would have been returned to the surface. In the debris the Gryphaea must have laid.

The Gryphaea were seeing the light of day for the first time in a very long time. This debris, from the borings, would have been scattered around the Cemetery. It’s hardly likely that it would have been carted away and there is no mention of it being moved away. As a result of the spreading of the debris these small fossils were strewn over a large area.

Well, that’s the best answer I can come up with anyway to explain their abundance..

Their presence in such quantities should perhaps cause us all to pause for thought. At one time they owned the site of the Cemetery. It truly was a Jurassic Park. An underwater one, true, but nevertheless it was their home.

Moving forward

Much, much later wild birds and aquatic mammals would have lived in this swamp land of the River Hull valley after the last ice age. Still later, hunters would have arrived and caught and killed these creatures. Setting up make-shift camps before moving on when the game dried up.

Still later, hardy sheep, goats and possibly cattle would have been driven on to the land in the summer when it dried sufficiently for grazing. When the winter rains came they would be driven back to stockades and huts on the high ground around Cottingham to live on hay until butchered and salted.

By the medieval period the site became permanent pasture land after drainage work. This pasturage and garden land was then transformed by the Cemetery Company into a manicured semi-forested area.

At present it has become a much more forested area than it has ever been. It’s probably at its peak now as a forest.

Change is the only constant of the universe

All of these changes have happened to this small stretch of land. Just 13 acres or about 8 hectares.

All of the above, from ancient oysters to forest trees have called it their home. And all have passed away as the present residents will at some point. There’s a small part of me that’s sad about that. There is, of course, a much greater part of me that is pleased about it too. These changes that have happened in the past and will happen in the future show that evolution continues. And without evolution life itself dies.

So, when people start getting exercised about such things, it’s as well to remember that. We’re not custodians. We’re just passing through like all the rest. And that includes the trees, the wildlife, the humans. We’re just a blink of an eye in the scale of things. Don’t get me wrong here. I would like all of the environment that I am familiar with to survive ad infinitum. It won’t but I’d like it to survive.

People talk blithely about ‘saving the planet’. I happen to know that the planet has, unless it is very unlucky and has some gigantic collision with another space object, at least another four billion years left. The phrase ‘saving the planet’ is totally meaningless. Trust me on this. The planet will be here long after we, the trees, the oysters have gone.

Taxi for Homo Sapiens?

When people use that term they are really saying ‘save the present environment so humanity, especially me and mine, can continue to exist’. Which is something similar to my comment earlier.

But, when you think of it, that is a pretty pointless exercise. We know the world will change, either by our doing (which seems likely) or some other factor (which also is likely). The only thing we should be confident about is that it will change. Just ask the Gryphaea. They lived in the sea and here they are now, buried metres underground.

We have our time now, just like the Gryphaea had theirs then. And when our time is over… well, evolution will carry on.

And after a million years or so we’ll leave behind less trace than the Gryphaea.

I find that strangely comforting after a few years of picking up the detritus that other people leave in the cemetery.

Pete Lowden is a member of the Friends of Hull General Cemetery committee which is committed to reclaiming the cemetery and returning it back to a community resource.