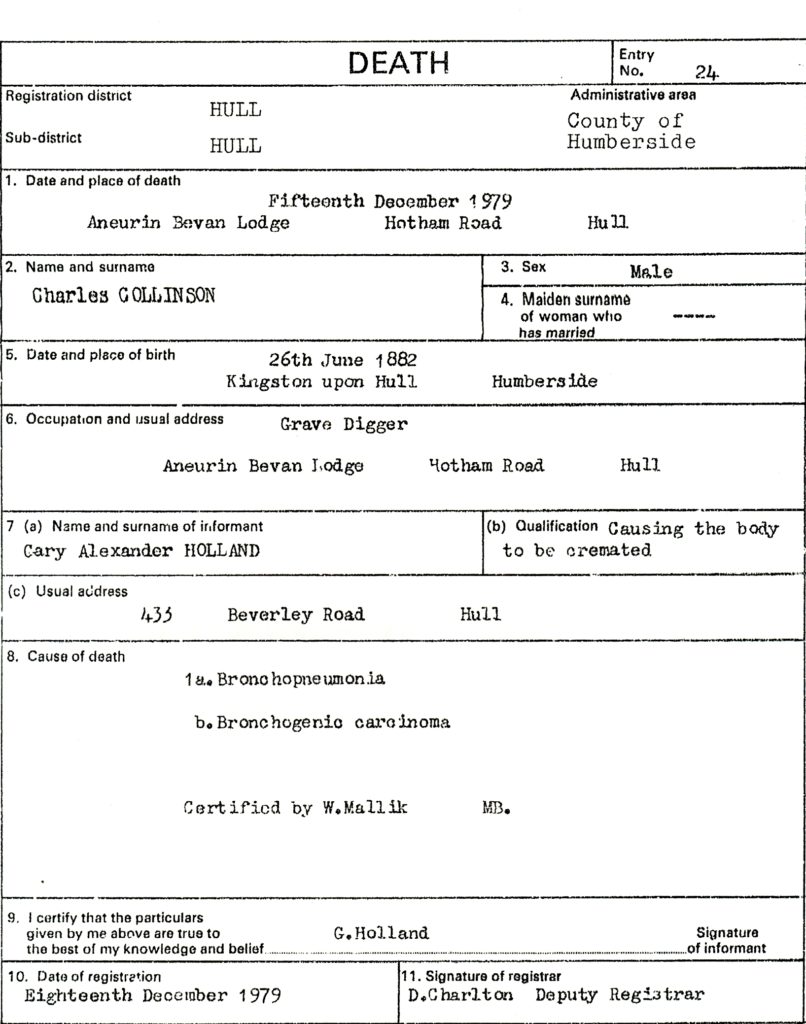

There was someone in the story of Hull General Cemetery who saw quite a lot of the changes in the Company’s fortunes. This man undertook the job without which the cemetery could not function. That role was as a grave digger. The person’s name was Charles Collinson. Obviously he was not the only grave digger that the Company employed throughout its existence. However he serves as a good example of someone who fulfilled that role.

His part is not widely known unlike many of the servants of the Company. He is not one of the great and good. His remains do not still grace the cemetery. However, in terms of longevity, Charles Collinson matches few other people whose lives were entwined with the cemetery. Here’s his story.

Early years

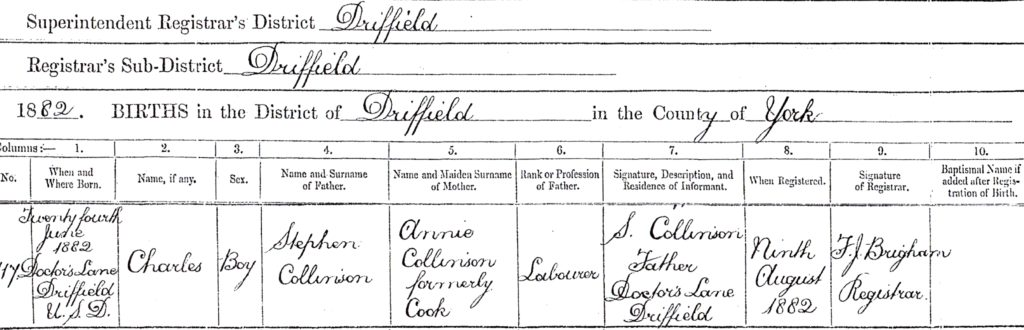

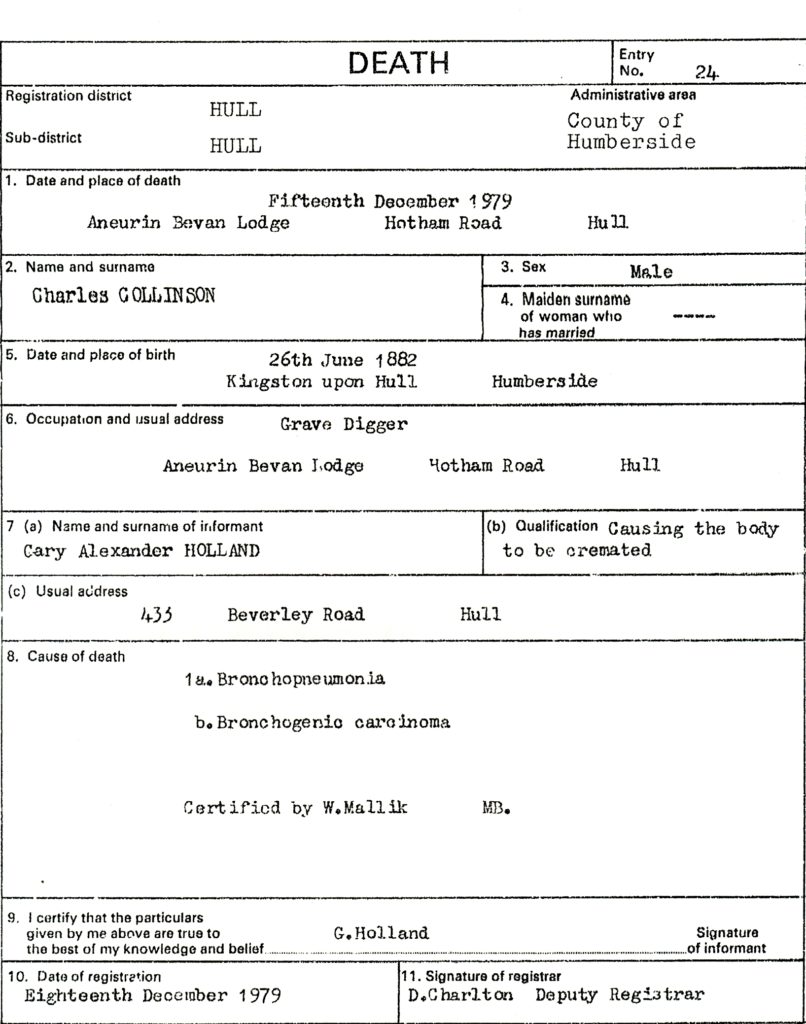

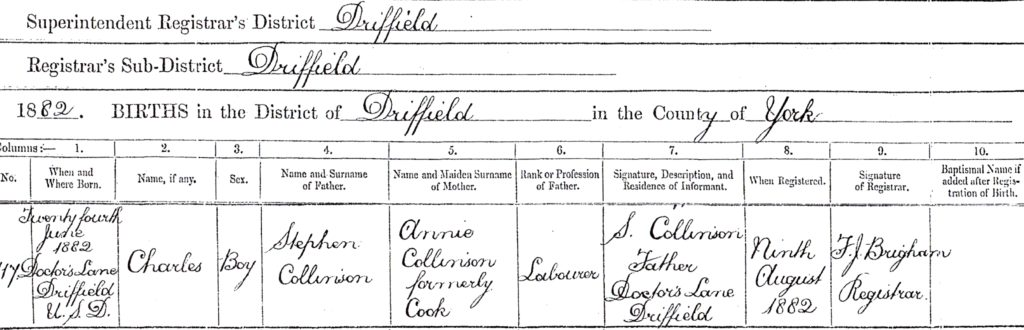

Charles Collinson was born in the June of 1882 in Driffield, East Yorkshire.

As can be seen from his birth certificate, his father, Stephen, was born in Bainton. His mother, Annie, born in Fridaythorpe. They were obviously a typical family living in rural Britain at that time. When mechanisation was beginning to make great inroads into agricultural practices. A time of change.

His father was listed as a general labourer in the 1891 census. A job with few prospects and one that was far from secure. The young Charles was also listed on that census as a scholar, aged eight, along with his elder sister Ada, ten, and his younger brother, George, six years old.

School

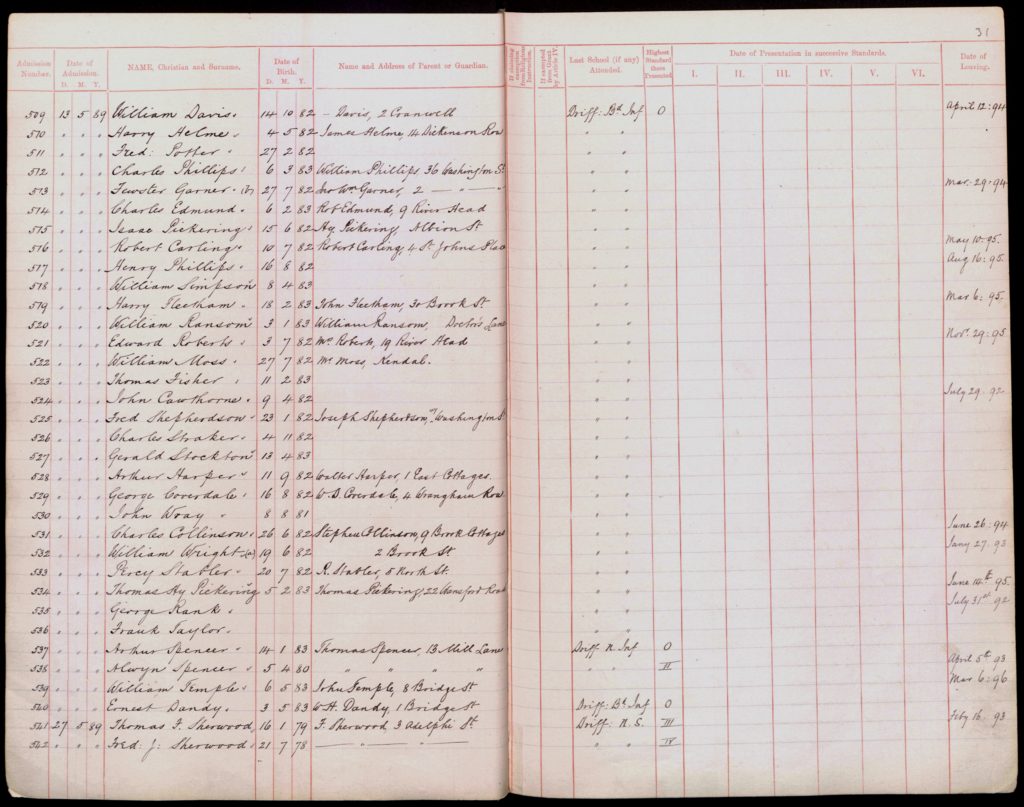

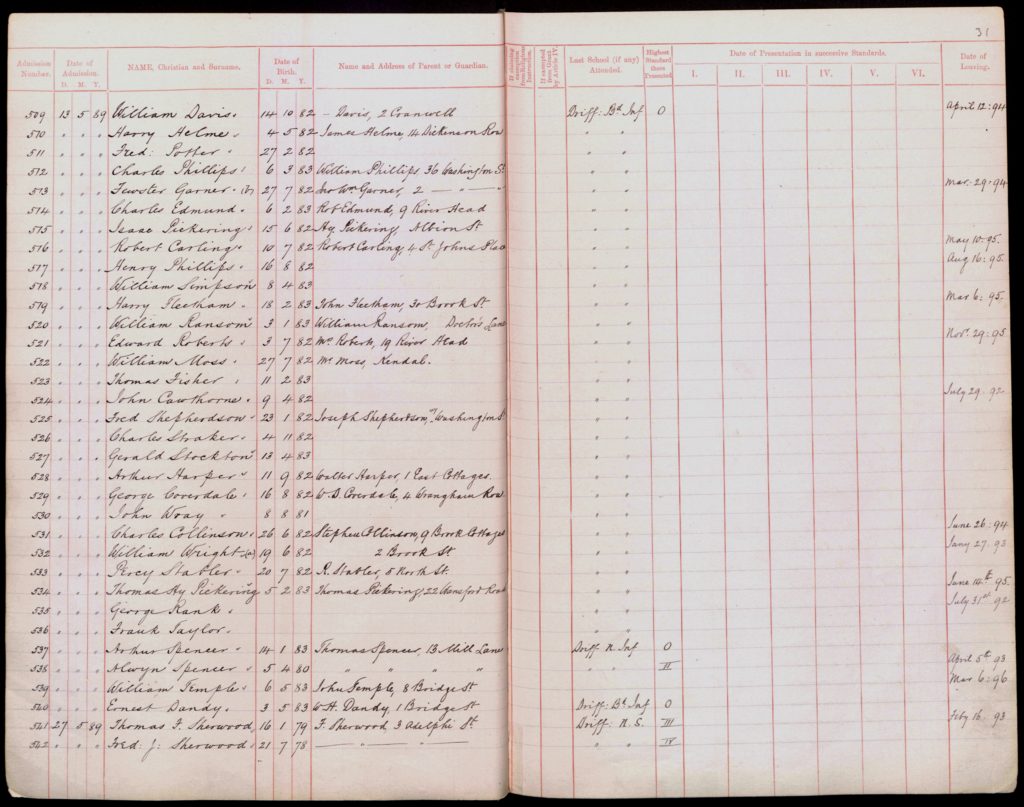

Charles attended the Driffield Local Board School. He enrolled there on the 13th May 1889 and left on the 26th June 1894.

He was lucky. Elementary education became an obligation on the parents of children from 1876 and by 1880 attendance at school, rather than home schooling, was compulsory.

This length of time in education was almost certainly the norm for that time. After all the education system of the period, at least for the working class, was fairly basic.

Literacy and numeracy, coupled with a smattering of rudimentary geography and history would have been the academic subjects covered. Sometimes sewing and basic crafts such as tailoring and shoe repairing were also added to the curriculum. And, of course, religious studies were usually mandatory. By 1899 the school leaving age was raised to 12 years of age.

As we can see Charles left on his 12th birthday and had enrolled a few days before his 7th birthday. Therefore he attended for roughly just over 5 years of schooling.

School attendance was often also worse in rural areas at this time. Young children had been used since medieval times for some mundane tasks. Crow scaring, tending flocks, stone picking; all were jobs that a needy family would have expected their offspring to do. It was well known that village schools would have poor attendance during harvest time. So, out of that 5 years of schooling, we have no way of knowing how much time Charles actually spent in the classroom.

Work

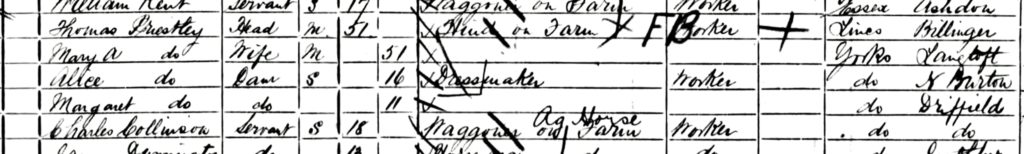

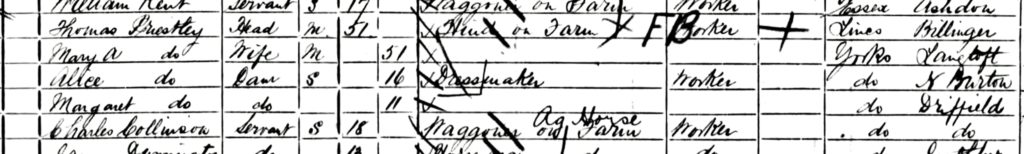

The next time we encounter Charles is in the census of 1901. He is no longer living in the parental home although he still lives in Driffield.

As you can see from the above, he is now 18 years old and is now a boarder.

The head of the household is a farm hand and Charles is listed as a servant. It is unlikely that a farm hand would have been in a position to afford to employ a servant. So, it’s more likely that Charles was the servant to a local farmer and drove one of the farmer’s wagons.

The prospect of Charles following in his father’s footsteps was extremely likely from this census entry. However, that didn’t happen.

Marriage

We next meet Charles on his wedding day. We do know that he married Gertrude Harriett Putt in 1906. The marriage took place in Driffield and Gertrude was a Hull girl, from the Hessle Road area. Her family was steeped in the fishing community ways. All the females in her family had been listed on past censuses as net braiders or fishing net menders.

So, here is a question that I don’t have any answers for. How did these two people meet? I can theorise but that’s all it is.

Its probably more likely that Charles travelled to Hull rather than Gertrude to Driffield. I’ve written before on other sites on this topic. The towns and cities of Victorian Britain only maintained their massive population growth due to immigration from the rural hinterland. Child mortality being what it was, without this immigration town and cities would quickly have become deserted. So, its reasonable to suspect that Charles came to Hull to escape the life of a ploughman.

He may have been forced into this. Agriculture at this time was shedding many jobs due to the introduction of machines. Threshing, baling, ploughing etc., were all jobs previously done by hand but now were mechanised. So it’s reasonable to suggest that Charles came to Hull rather than Gertrude going to Driffield.

Looking around when he arrived in the big city, and being a farm boy, I would suspect that factory work was probably not to his taste. What else would appeal? The fishing industry was in its heyday but perhaps Gertrude warned him against that prospect. She’d have seen enough tragedy related to that kind of work living where she did. Construction work was a possibility but it was subject to seasonal fluctuations and was not seen as a steady job.

City life and parenthood

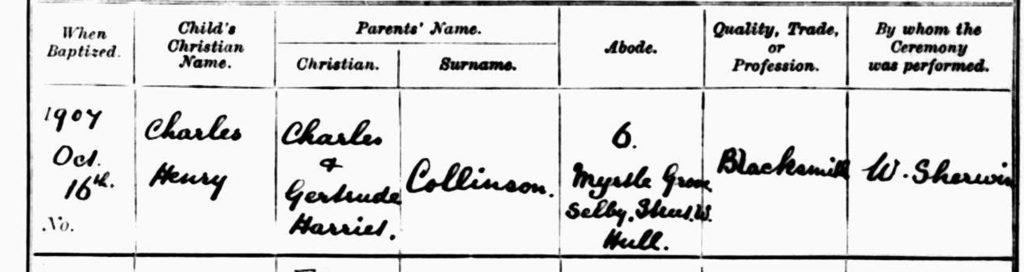

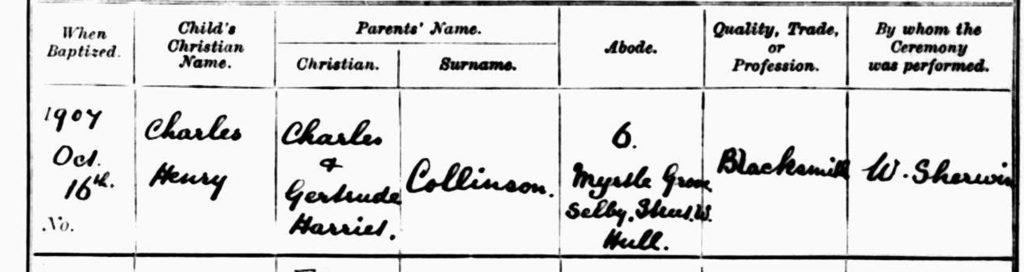

Now what job would be transferrable from the rural to the urban setting? Think horses. Yes, Charles became a blacksmith. We know this from the baptism record of his son, Charles Henry Collinson. This boy was baptised on the 16th October 1907 at the parish church in Driffield. Yet the address given was 6, Myrtle Grove, Selby Street in Hull. Selby Street in 1919 is pictured below.

They had travelled the 20 miles or so from Hull to Driffield to celebrate the christening of their son with Charles’ family (and possibly Gertrude’s too). My imagination sees a hired wagonette, gaily festooned, and full to the brim of relatives out on a ‘Beano’ to celebrate the christening. Lets hope they stayed overnight.

Blacksmithery was a good trade. However, by the first decade of the 20th century, horses were soon to be a thing of the past. Charles, I suppose, would have been looking round for something with more future. Now, I do admit this is tenuous, but a job as a grave digger offered both outdoors work and the prospect of steady work. I think he may have turned up at the superintendent’s office sometime between 1907 and 1911 and asked if the cemetery had any vacancies.

Back in 1974 I remember a younger version of myself doing much the same at the office at Pearson’s Park. I’d like to bet that Charles received the same answer that I did which was, ‘When can you start?’

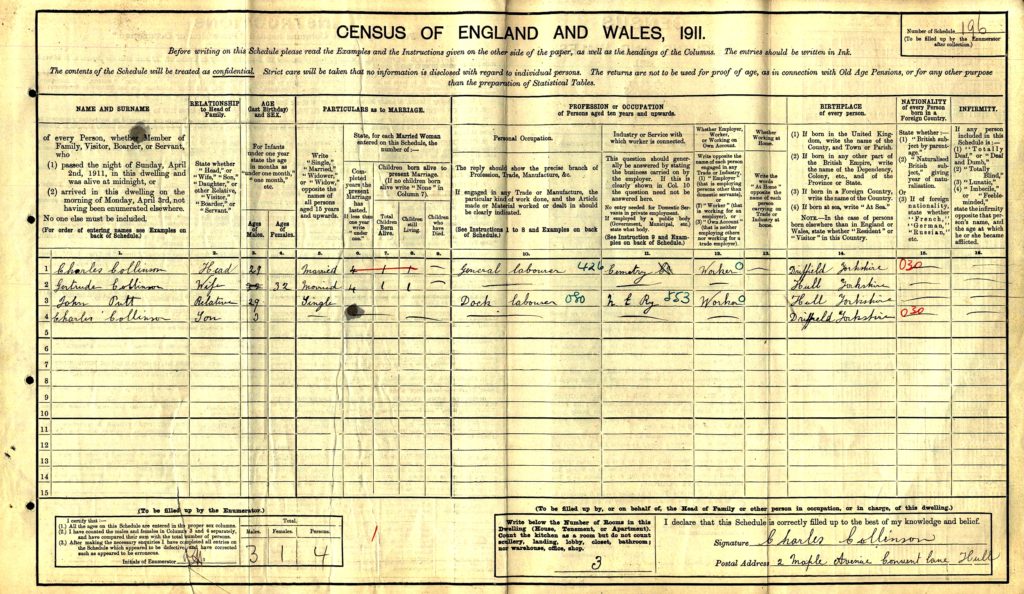

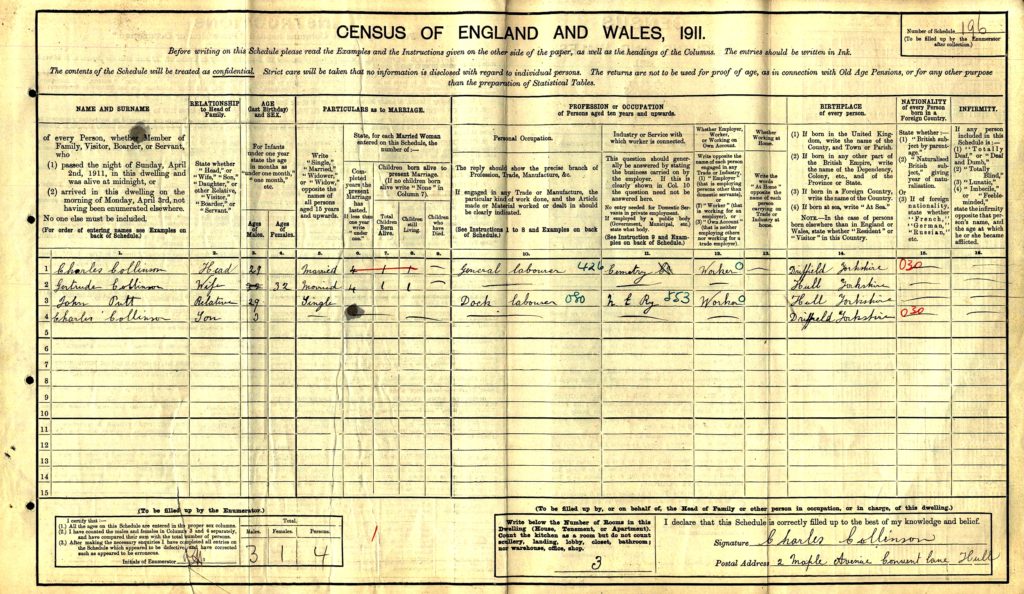

1911

So, with the 1911 census, we come to the first solid evidence that Charles worked in HGC. The 1911 census also gives us evidence that Charles or Gertrude were literate and numerate as the 1911 census was completed by the occupier. Sadly, the educated one was more likely to be Charles. Even though he experienced schooling in a rural setting, education for girls was often seen by the families and authorities as a waste. As such many girls and young women were trained as domestics where literacy and numeracy were not vital to the task of scrubbing.

Charles was now employed by the Company. There are so few records left with information about the actual employees other than the superintendents. It is quite refreshing to find records of others. In Charles Collinson’s case, this was the beginning of a long, and sometimes, turbulent relationship that lasted until at least the 1960s.

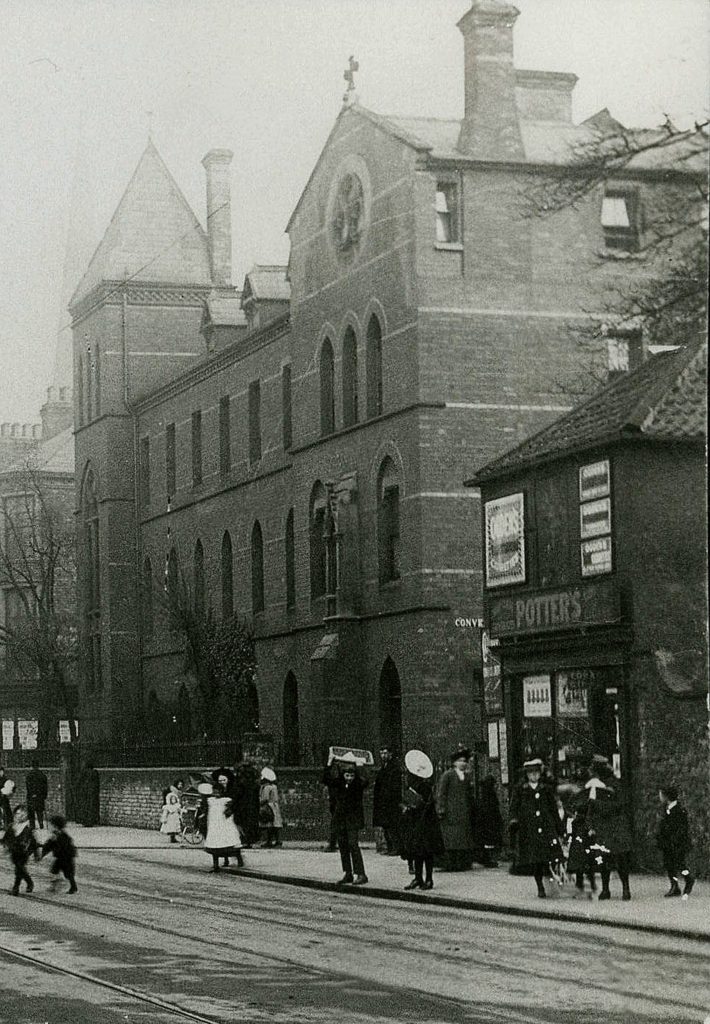

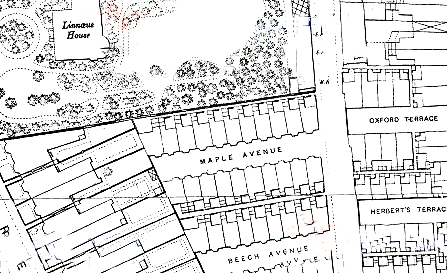

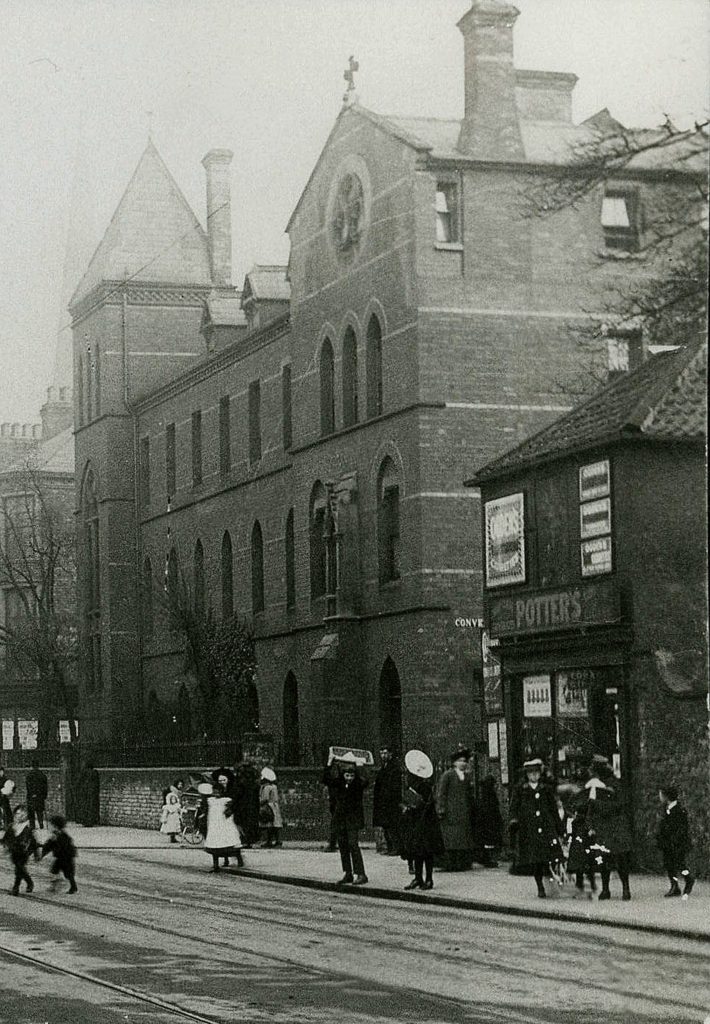

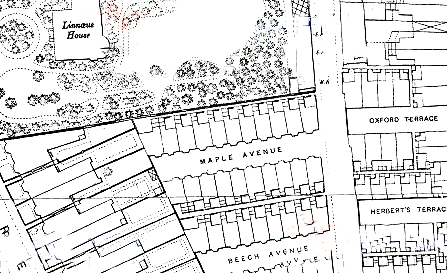

From the census form we can see that the Collinson family had moved from Selby Street, a little further down Anlaby Road towards the town. Their new address was 2 Maple Avenue, Convent Lane. The corner of Convent Lane and Anlaby Road is pictured below.

Holidays

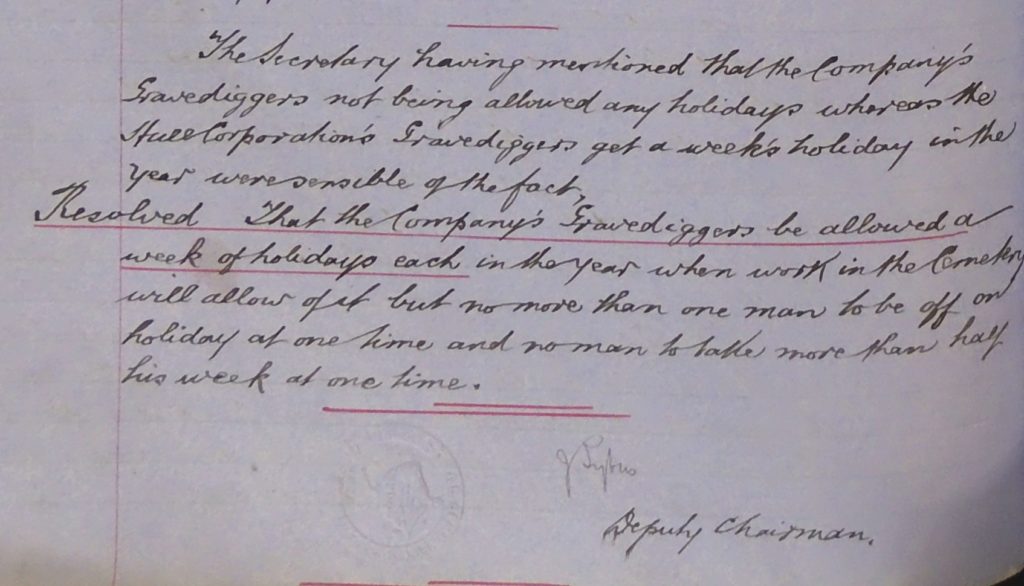

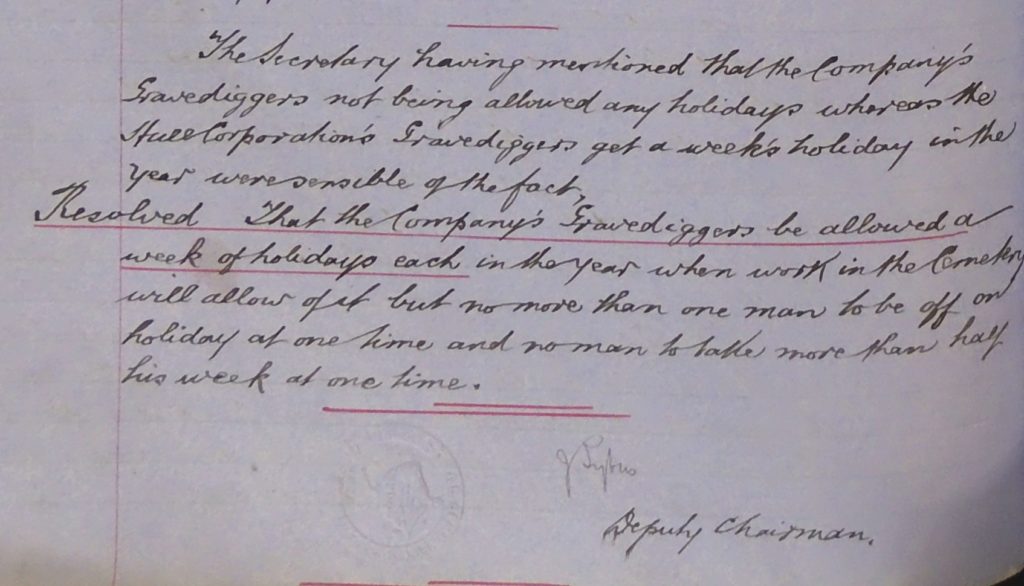

Charles joined the Company’s pay roll at an auspicious time. In the August of 1911 the Board was informed of a development. This was that their grave digging staff made a request to have holidays. Apparently they knew that the Corporation grave diggers just up the road in Western Cemetery were allowed such frivolities. The grave diggers wondered if holidays could be extended to them. A serious discussion took place and, in a spate of generosity not usually seen, the Board agreed to this request as you may see below.

The Great War

The next time Charles comes to our attention is during the First World War. You’d probably think that digging graves would be a reserved occupation. This was not the case. Unlike train drivers, coal miners and farm workers, grave digging was not seen as vital to the war effort. Of course, the government wanted the dead burying, if for nothing else, than to keep up the morale of the people. And, in a perfect world, such workers would not have been required to serve in the forces. Sadly, by 1916, the losses in the conflict had reached such proportions that conscription was imposed to fill the gaps.

In January 1916 the Military Service Act went through Parliament and single men could be compel to enlist in the forces. By the June of that year the Act had been amended to include married men. This meant that Charles, being a man in his thirties, was in the frame for being called up to the colours.

That very month the papers arrived and although the Company sought to having him exempted they withdraw their objections when they managed to get someone to replace him. So Charles went off to the Army.

Unfortunately I have not found his Army record. It may well have been part of the cache of Army records that were destroyed by enemy action in the Second World War. We do know he was conscripted and served. We also know that when he was released from military service. He returned back to his old job as a grave digger in the Cemetery on the 11th February 1919.

Back home

During the early years of the 1920s the wages of the staff of the Cemetery was comparable to the Corporation’s staff. During the First World War scarcity of labour had allowed wage inflation to take place. Its doubtful if Charles gained from this experience much. When he returned to his grave digging post he probably was surprised at the amount he was paid. Touching over £3 10s per week it would have been a welcome sight.

Sadly it wasn’t to last. From 1922/3, the economy began to contract, especially in the old heavy industries such as ship building and mining There was now a surplus of labour. As a result wage contraction and unemployment set in. By 1926 this resulted in the General Strike.

The grave diggers had had their wages reduced gradually over this period. By April 1924 the wages had been reduced to £2 17s 6d. The manual staff, I’m pretty were sure grumbling to themselves. However, probably looking around at the wider world, I’m also sure they will have kept their heads down.

Sherwood Avenue

Around this time Charles and Gertrude moved into their final family home. No.4, Sherwood Avenue, Welbeck Street. Both Charles and Gertrude, hopefully revelling in her new found right to vote, are present on the electoral rolls for Spring 1921 at this address.

Above is the Sherwood Terrace name plate and below is No 4, Sherwood Terrace today, with HGC as the backdrop to the right.

The 1930s

Charles next comes to our attention via a brief mention in the Company Minute books for 1931. He and his fellow workers, Tebb, Hunt and Wilson were to receive a Christmas Box from the Company totalling 30/-. This was divided up into 10/- for Collinson, 7/6d each for Tebb and Hunt and 5/- for Wilson. So why did Charles receive the lion’s share of this largesse? The answer is simple. Charles had now reached the elevated position of Foreman grave digger. Having worked for the Company for over 20 years he had reached, probably, the pinnacle of his desires. Later in the decade it was all to come crashing down.

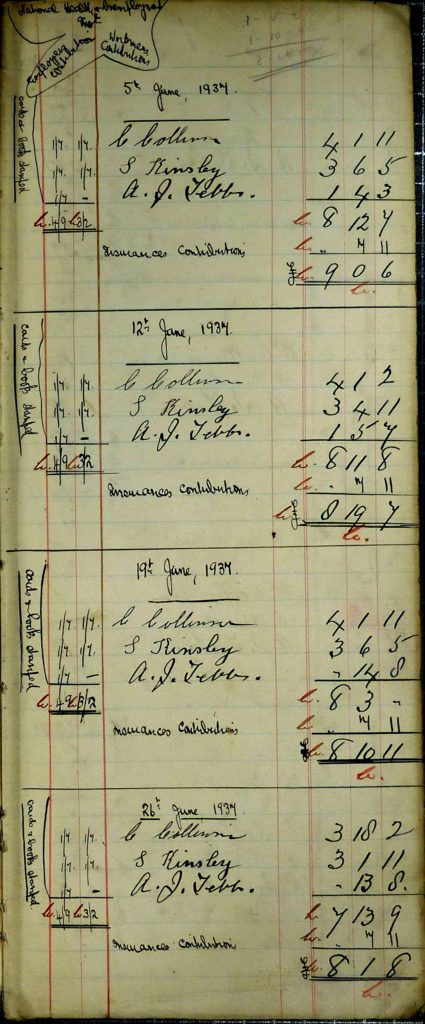

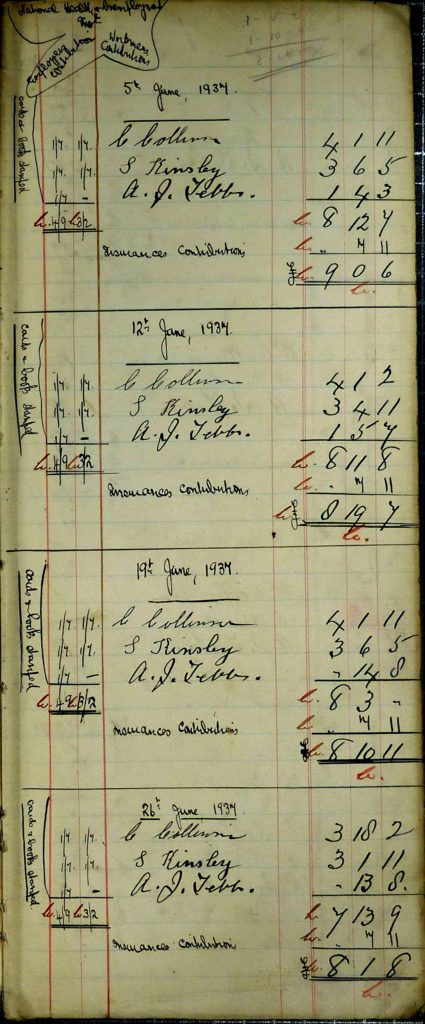

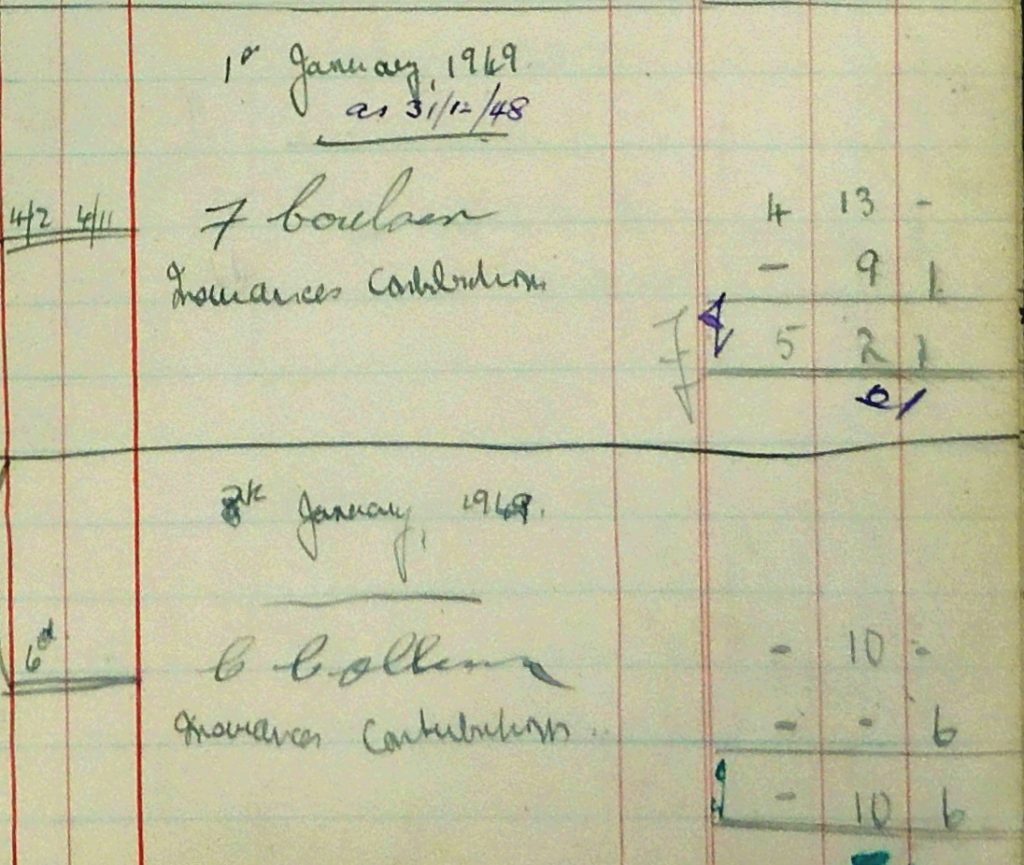

Some of you may remember me lamenting Michael Kelly’s disposal of some of the Hull General Cemetery’s documentation during World War Two. One thing that has survived this rash act of destruction are a few pages of a wages book of the period.

As you can see by 1937 Collinson was still the Foreman grave digger. Another grave digger was Kinsley and the residual arm of the now defunct stone yard staff was Tebb whose pay was dictated by the work he had to do.

Tebb received 1/7d per hour and extra for the lettering he did. In stone he received 10d a dozen, in marble 1/1d a dozen and finally in granite 2/7d per dozen. But as you can see in the above wages book this man’s wage varied greatly.

1938

The year 1938 is important in modern history. It was the highpoint of the appeasement policy by Britain and Frnace of the dictators of Europe. The image of Neville Chamberlain waving a scrap of paper on Croydon Airfield after returning from Munich are redolent of a shameful period in our history. With the western democracies betraying the Czech people to seven years of brutality under the Nazis and 45 years under Soviet control it was a time of national shame.

Coincidentally the year was one of shame for Collinson too. By this time Charles was now 56 years old. He’d been employed by the Company at least 27 years. He’d probably risen as far as he could in its service. He lived close to his place of work in a nice little two bedroomed house in a nice area. What could possibly go wrong and spoil this idyll?

The Hull Daily Mail

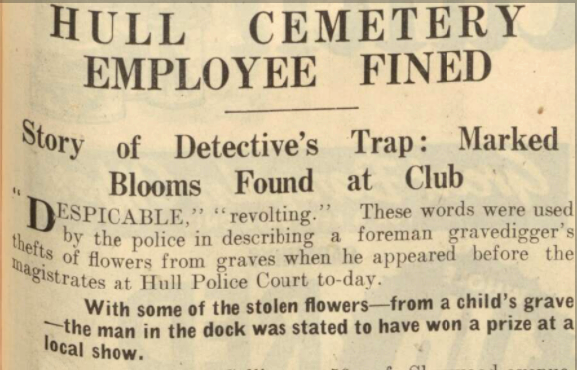

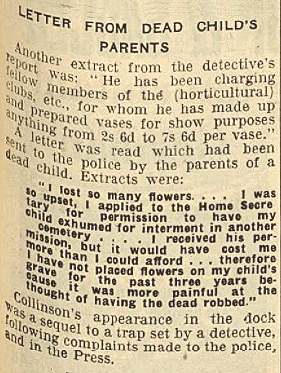

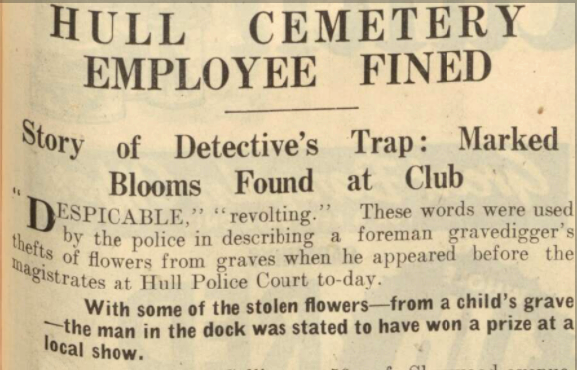

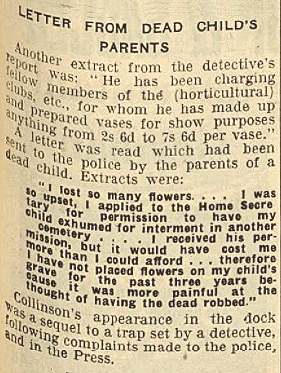

The Hull Daily Mail of the 26th September ran a headline that did just that.

It read, ‘Robbed Child’s Grave to Win Prize at Flower Show.’ Here was Charles Collinson’s Munich.

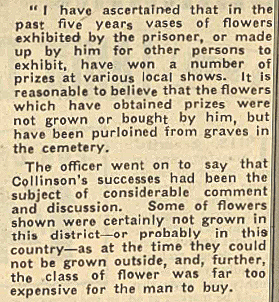

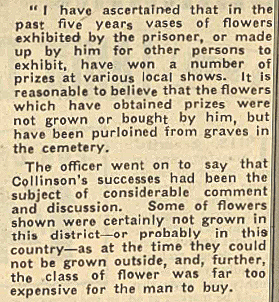

And that man in the dock was Charles. Apparently he had stolen , for a long period, choice blooms from graves to enhance his chances of winning local garden shows. Perhaps not showing a great deal of intelligence, he produced winning displays, consisting of exotic flowers, that he claimed he had raised himself. The organisers of the shows had had their doubts about Collinson’s flowers’ pedigree for some time but kept these doubts to themselves.

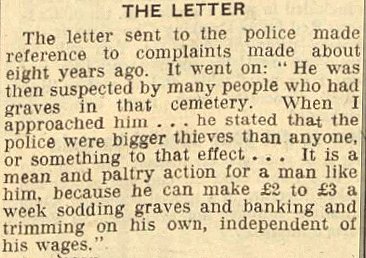

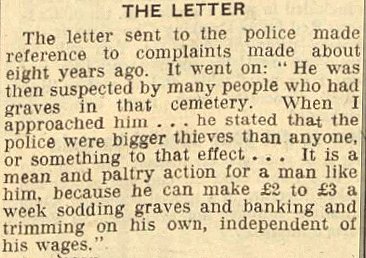

No, it wasn’t the success at the flower shows that caught Collinson. It was the actions on the part of the bereaved who saw their flowers disappearing and complained. Complained to the Cemetery and the Police. One of them had even written to the Home Secretary with the aim to have his child exhumed from the cemetery all together.

To catch a thief

The police used a novel method to capture the perpetrator. They marked flowers with pin marks on a grave that had often been targeted. The next day, out of 12 chrysanthemums placed on the grave, only seven remained. The police must have had a good idea who was committing the thefts as they then went to a local flower show and watched Collinson prepare a vase for display. After he had left the show they took possession of the vase and found two of the marked flowers. The police searched his greenhouse where they found two more chrysanthemum blooms marked with a pin hole.

During questioning about this, Collinson said he had bought them from a local shop. When told he was suspected of stealing them from graves he said he bought them in the Market Hall.

Detective Bishop informed the Hull Daily Mail that they had received numerous complaints over the last five or six years.

The article went on to say,

And so we come to the judgement of the Magistrates. But first let’s look at how the Company dealt with this shocking news.

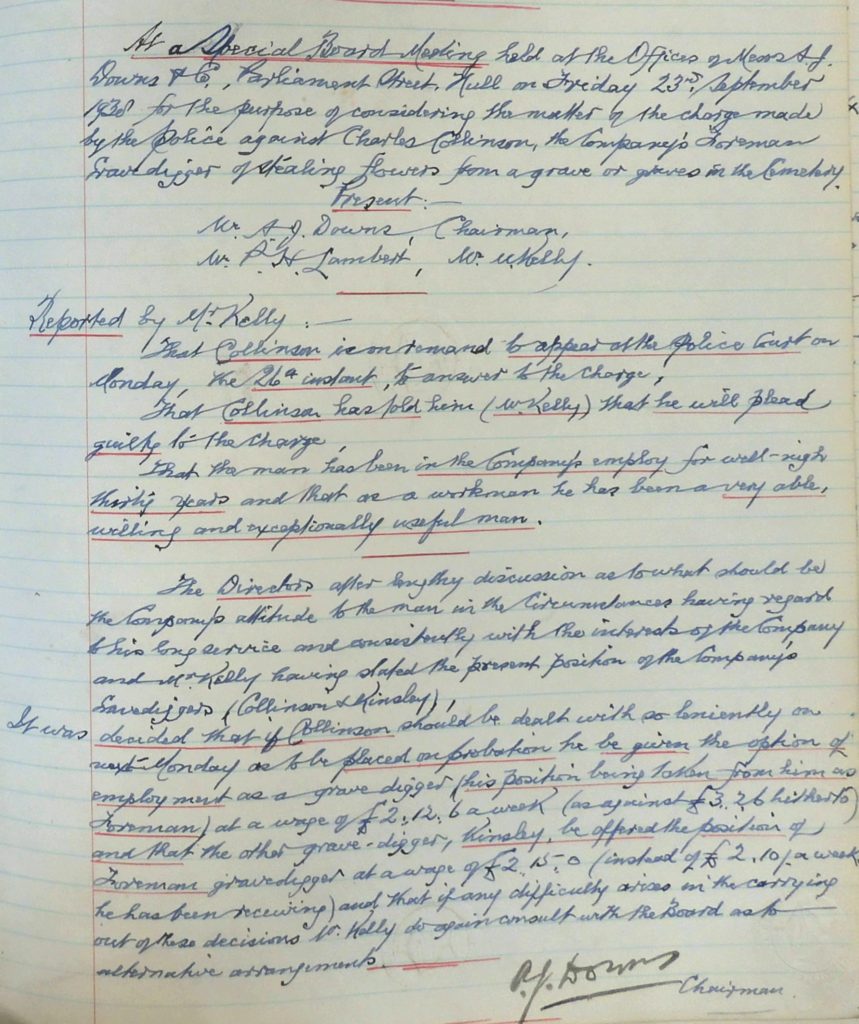

The Company’s view

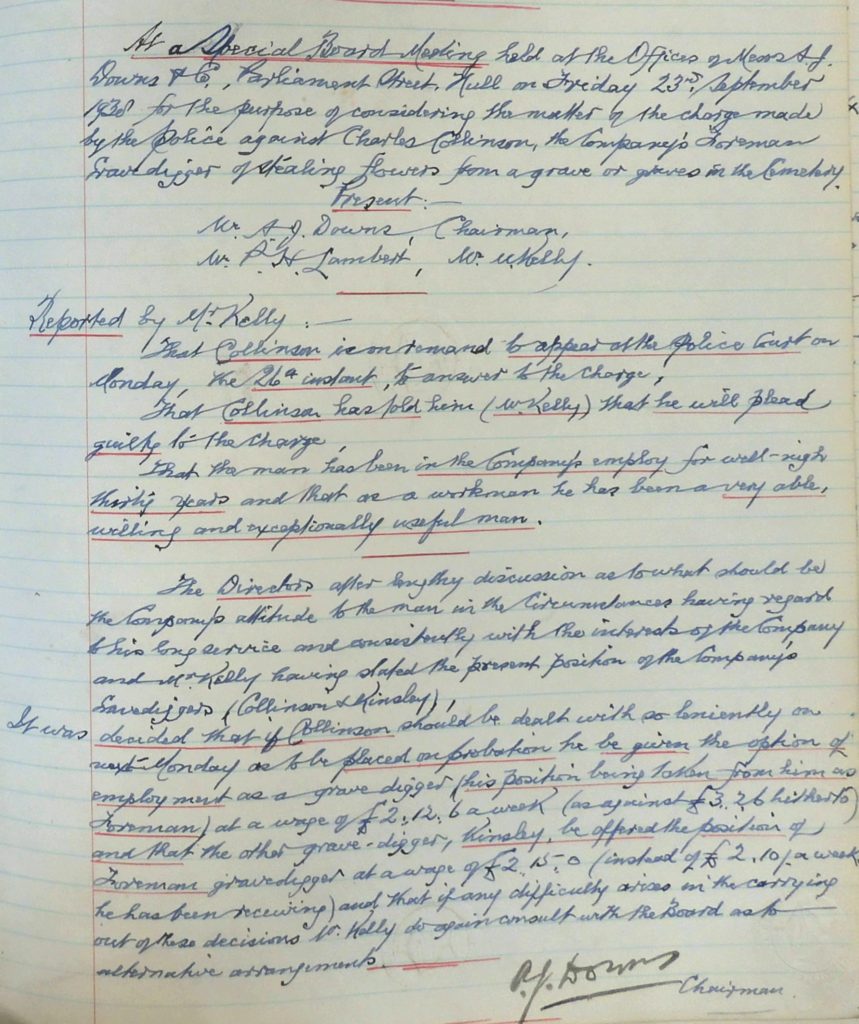

On the 23rd September, some 2 days before the case came to Court, the directors, at an Special Board meeting, discussed the ramifications of it. Michael Kelly, the superintendent, informed the Board that Collinson had told him that he intended to plead guilty to the charge.

So, as you can see, if the Court did not impose a custodial sentence upon Collinson, the Company were prepared to continue his employment.

A step down

His position would be inferior, as would be his wages, to his present position. However, he would still be employed. Another interesting point is that Kinsley would now be the Foreman Gravedigger, yet the Company chose this moment to reduce not only Collinson’s wage but also to reduce the wage that the foreman would earn. In essence the Company won both ways.

The magistrates did act leniently towards Collinson. He was fined £5 with the alternative of 30 days imprisonment. Collinson chose the fine. The Court said they had taken a ‘very considerate view of the case’. During the hearing they had heard from Michael Kelly about Collinson’s record of work at the Cemetery but this was not a vital factor that allowed the Court to act in such a way.

No, sadly, there was another more important factor that gave the magistrate’s their opportunity to be lenient

Gertrude

As we have seen Gertrude had married Charles in 1906 and had borne a child, a boy, in 1907. Since then her presence in this story has not been great. Now it does. The magistrates had mentioned in their deliberations, reported by the press, that Collinson had a sick wife. It was probably this factor that had stopped Collinson going to prison.

We know little about Gertrude’s illness.

Of interest she is not recorded at the house in Sherwood Avenue on the 1939 register. Yet, Charles is, and he states he is married. So any marital difficulties that the trial may have thrown up are not apparent. I would surmise that Gertrude was in hospital at the time of the taking of that register.

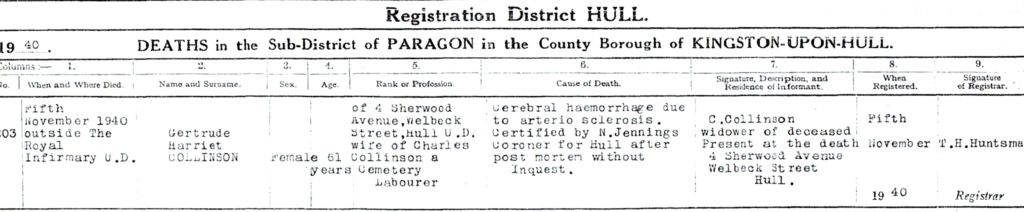

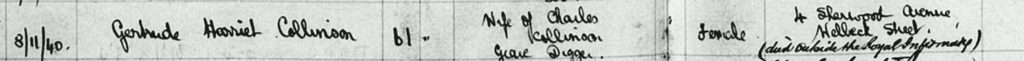

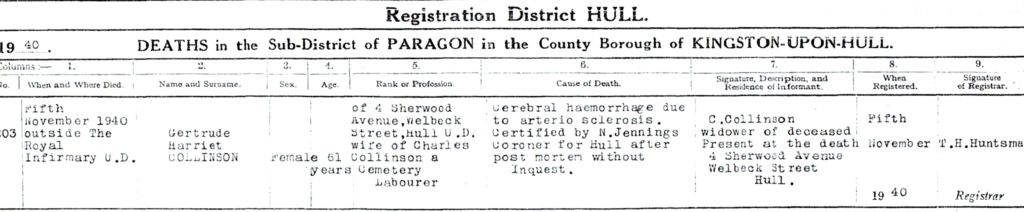

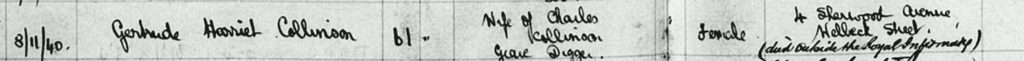

I am basing this assumption on her death certificate.

The cause of death

The cause of death is interesting. Basically Gertrude died of a stroke or heart attack. Fatty plaque deposits thickening on the walls of the arteries, eventually leading to a blockage that results in a stroke or heart attack is quite common now. In the past such incidents were less well diagnosed. Often sudden deaths such as this were termed apoplexy and even further back in time, visitations.

One of the side effects of this disease is vascular dementia. We are familiar with senile dementia today. Vascular dementia is similar in its effects but the cause is many small mini-strokes that damage the brain cumulatively. Symptoms are weeping, apathy, transient befuddlement. Such symptoms in the 1930s and 40s may well have meant some care in a hospital. Worse cases would have probably been cared for in mental establishments. Was this where Gertrude was on the night of the 1939 register?

I also note that she died outside the Royal Infirmary in Prospect Street. Were Gertrude and Charles entering or leaving the Infirmary when she died? Charles states that he was present at her death. Knowing that a heart attack or stroke is a matter of moments, Charles must have been by her side rather than being called to her side from home or work.

Yes, of course much of this is supposition, but it does chime with the facts that we know. Gertrude was buried in HGC, in the same grave of her son, Charles Henry.

Charles Henry

We saw the christening of Charles Henry in Driffield and I had hoped that there had been a suitable party to celebrate. We then saw Charles Henry in the 1911 census. A child of three. Our next chance to check up on him would be the 1921 census, to be released in 2022. He does not feature in any register or record set that can be accessed at this time. Apart from, that is, the record of his death.

Charles Henry Collinson, a youth of 19, died on the 21st October 1926 and was buried on October 25th. His cause of death was heart failure as a result of pulmonary tuberculosis. TB was rife in these times and was known as the silent killer. In Victorian times it was often termed consumption.

The cause of the disease was not known for along time. Simon Wills states in, How Our Ancestors Died, that the medical profession cited many reasons for catching it, ‘consumption of alcohol was linked to to the cause of TB , as was masturbating.’

In 1882 Koch, famed for his work on cholera, discovered that TB was caused by a type of bacteria. Unfortunately that didn’t make it easier to avoid catching it. My paternal family in Dundee, between the period of 1870 and 1878, lost four members of the family all from TB. Living in crowded tenements its difficult to see how one could avoid it. My great grandfather did, but only by going to sea at 14 years old.

A TB sufferer would expel the bacteria every time they coughed and coughing was what they did a lot of. Some times the coughing fits themselves were dangerous and I believe that this is what happened to young Charles Henry. That during a violent coughing fit his heart failed under pressure. The family grave is pictured in the foreground of the image below.

Charles alone

So, in the midst of the Second World War, Charles was left alone. We have no knowledge of any extended family he could turn to. It’s possible that he still had one of two contacts amongst his gardening friends but his conviction may have soured that type of relationship. The only thing he had left was his work.

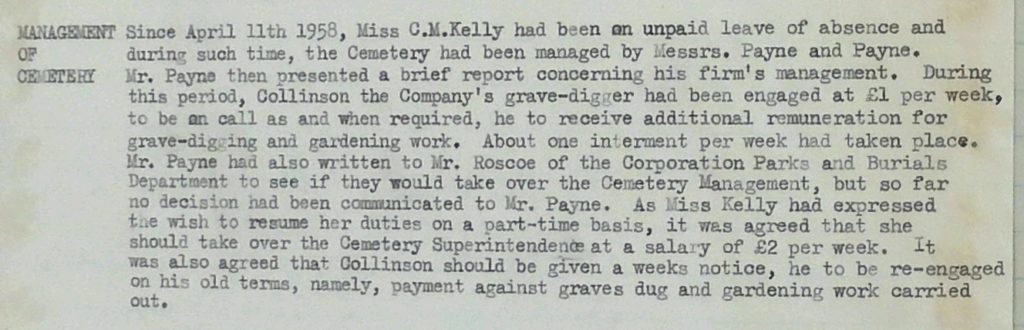

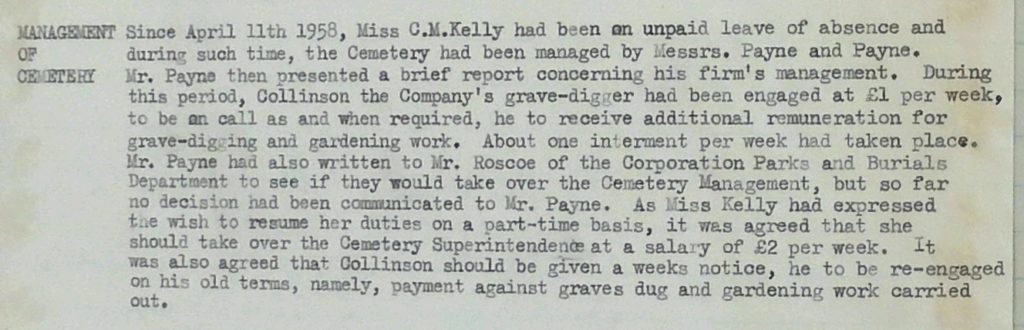

Luckily, he was now much too old to be conscripted for the forces in this war. So his job was safe. Not only safe but enhanced. Once again the armed forces recruitment meant a shortage of labour. With the result that wages rose. In Collinson’s case the war also meant that he was now the sole remaining grave digger as Kinsley had been called up for service in the Royal Navy in the October of 1939. He was once again the Foreman grave digger, but he was only in charge of himself.

In September 1941 Michael Kelly reported to the board that he was having great difficulty in recruiting labour owing to the war. By 1943 Collinson was earning £3 17s a week which was over a £1 more than at the start of the war. Collinson was now aged over 60 years old. And it probably showed in his work.

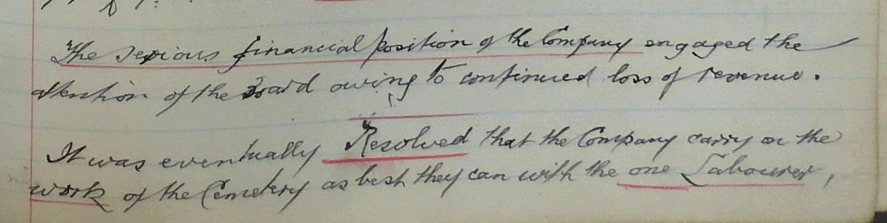

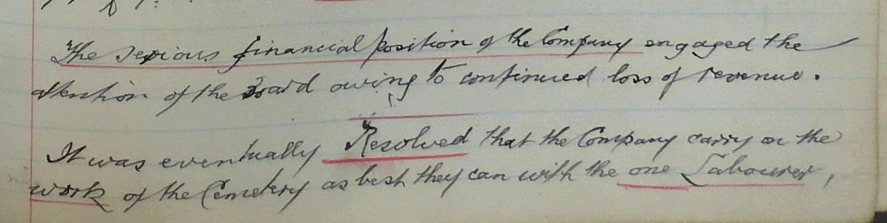

Time to go?

In July 1945 at a Board meeting it was suggested that a replacement for Collinson should be sought as he was, “now (an) aged man and unwilling or unable to do any more work than he is obliged to do now, namely grave digging.”

This plan didn’t work. They did manage to employ a Thomas Stanworth as a a labourer in the November but also had to increase Collinson’s wage to £4 10s as, unsurprisingly, finding people willing to dig graves is not as easy as it sounds.

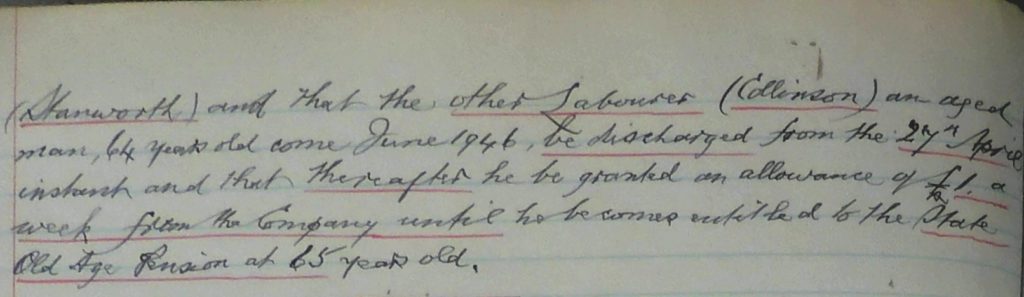

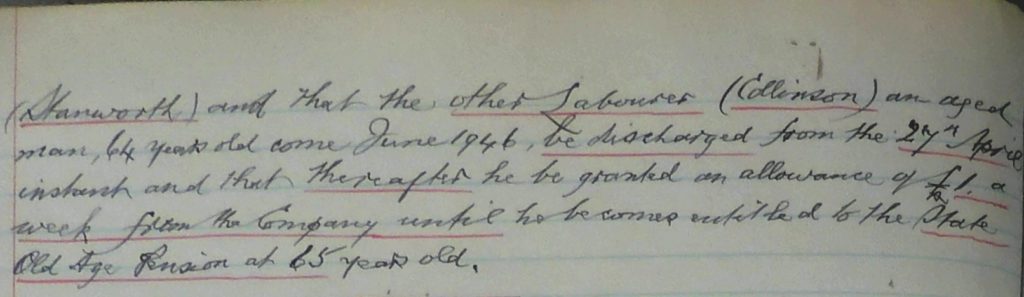

By April 1946 the Board had decided to dispense with Collinson.

A strange decision. Elements of paternalism yet quite brutal. However this decision shows the situation the Company now found itself in. Where the saving of £3 a week on a wage was important yet the Company also recognised a debt of loyalty to Collinson. It was all hot air anyway.

By the next month the Board had reversed its decision and both Stanworth and Collinson were reprieved. This may be due, in part, to the resolution of a concurrent debate in the board room. This debate was, how could they reverse their generous decision. made only two years previously, to give an annual pension of £200 to Michael Kelly.

Michael Kelly, had been the superintendent of the Cemetery since the 1890s and was an ill man at his retirement. Indeed he died in 1949. As a gesture to his long service and extremely good handling of the affairs of the cemetery this pension was given. By the May meeting of 1946 the matter was decided,

“The directors gave full and careful reconsideration to the several matters referred thereto at the last meeting of the Board and in the light of all the circumstances. As they now appear it was resolved that the sum of £250 in value of 3% War Stock be given to Mr Kelly on the 31st inst. as an outright payment in lieu of the pension hitherto given him and resolved further that the wages of the labourer’s Collinson and Stanworth remain as at present, namely £4 10s and £4.8s respectively subject to revision in 6 months’ time.”

Stanworth didn’t wait for any revision and left the month after. He’d seen what the Board had done to its most faithful servant, Michael Kelly. He must have guessed that whatever ‘revision’ happened it wouldn’t be positive. And it wasn’t.

Collinson, of course, had nowhere to go. At 64 he was virtually unemployable and by now, he was probably reluctant to change his habits. He would wait for the results of the revision.

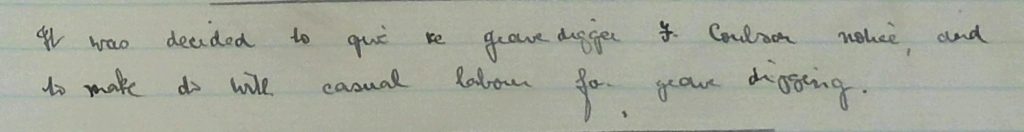

Frank Coulson

In the October that year a new name appeared. This man’s name was Frank Coulson. A Londoner, and known as ‘Cocker’ probably because he called everyone ‘Cock’, he featured in my life too. He was my first foreman at Northern Cemetery back in the 70s. However this was his first job as a grave digger. He shadowed Collinson for a week, learning the job and at the end of that week, Collinson’s long service with the Company was terminated on the 19th.

As Lord Stafford said on the scaffold in 1641, ‘Put not your trust in Princes’. Frank should have taken note. Some two years later Coulson himself was sacked. Not because he was a poor worker. Indeed he kept the cemetery going singlehandedly. No, it was the dire financial circumstances that the Company now found itself that they could not afford his wages.

Reprise

So where was Charles? Was this the final part in his long acquaintance with the cemetery? As he has really left the stage?

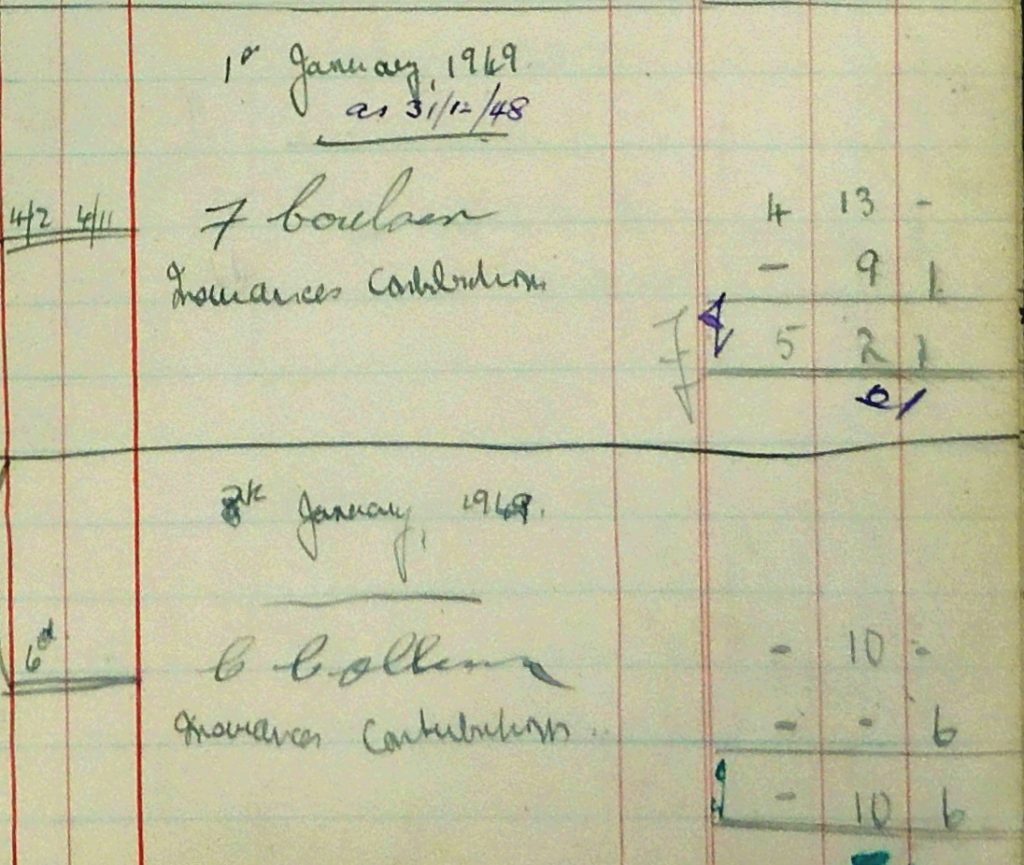

No, of course not. The week after Coulson’s employment was terminated, Collinson was back on the payroll. the change, as demonstrated by the page from the wage book, was seamless.

We have no knowledge of who made the first move to rekindle the relationship. I would suspect that it was the Company. In December 1948, when Coulson lost his job, the Board had stated that grave digging would be done on a casual basis. This would have meant that they could employ Collinson’s skills on an ‘as and when’ basis. This arrangement would have probably suited Collinson too as by this time he would have been receiving his old age pension.

And so Charles Collinson, who’d probably known the cemetery in its Edwardian pomp, with a large workforce, was the last grave digger. Indeed the last manual worker for the Company.

The 1950s

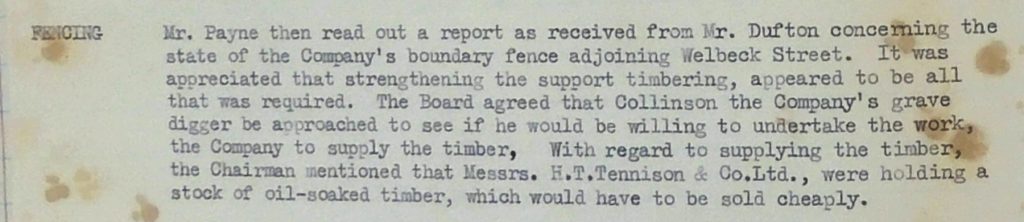

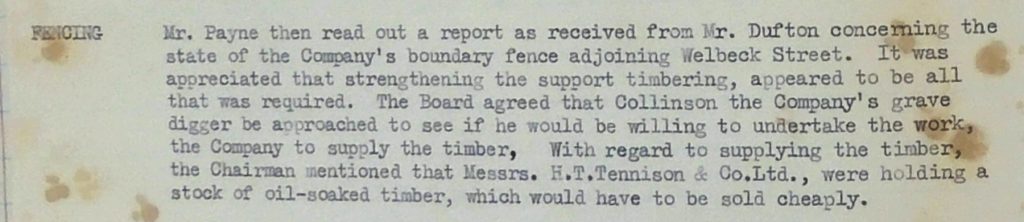

Collinson doesn’t feature much in the years afterwards. He crops up in April 1957. By this time he would have been 75 years old. The Board meeting of that month makes mention that Collinson may be able to patch up the fence near Welbeck Street.

As you can see from the wording above, Collinson was now being asked to do jobs rather than told to do them. I would think that whether he did them was dependent upon whether he had the stamina and strength.

At this board meeting the directors also spoke of their agreement with Sam Allon Ltd to demolish the stone yard. Sam said he would do for free if he could keep the materials. The Company were delighted. In the end Sam Allon must have made a profit for he gave the Company £15 afterwards.

The last of the Kelly’s

In August 1957, the Board were informed that both Ann and Cicely Kelly, Michael’s daughters, wanted to retire. Ill health was cited.

Cicely also mentioned that Collinson had ‘expressed a wish also to give up his duties.’ Was Collinson influenced by the Kelly sister’s imminent retirement? Did he see this as an indication of an end of an era? After all he had seen the stone yard demolished recently and the superintendent’s house had recently been converted into flats.

As I said at the beginning of this piece, Collinson witnessed many changes in the Cemetery’s life. He may have seen enough.

By the following May, Ann had died. At the Board meeting that month the management of the cemetery was discussed.

Sporadic glimpses of Collinson emerge after this.

In a letter from Payne & Payne, accepting that some nuns could be exhumed and re-interred in Northern Cemetery, it is mentioned that,

“It would perhaps be well to make it clear to Mr Moses (the undertaker) at the outset that it is no use relying on Charlie Collinson to do all the necessary manual work, because although I dare say Collinson would like to supervise the job, I think at over seventy, it is asking too much of him.”

The old retainer

In the same year, and from the same source, the Company’s solicitors, who were now managing the cemetery, another mention of Collinson is made.

“Dealing with the loss of Collinson’s ladder, I think we should perhaps offer to help him with the cost of materials if he himself is building a replacement. As you know unless he can use the short cut over his back wall into the cemetery, he has rather a long walk on to the job, but I will leave this to you to deal with as you think best.”

There is an element of paternalism here now in talking of Collinson. He has almost assumed the role of the old family retainer; still present but unable to do what he used to do but no one has the heart to tell him to go.

Our final glimpse of the man on a personal basis comes from the same source, the Company’s solicitors. On the 25th June 1960 a letter was sent to Collinson. It read,

“Dear Mr Collinson, it has come to the Director’s notice that the 26th is your 80th birthday. The directors have asked me to take this opportunity of passing your birthday greetings from them, and also to express their continuing appreciation of your services to the company.”

Unfortunately, the letter is some two years early as he was only 78 at the time. Still, I’m sure it was a nice surprise for him and good gesture from the Company.

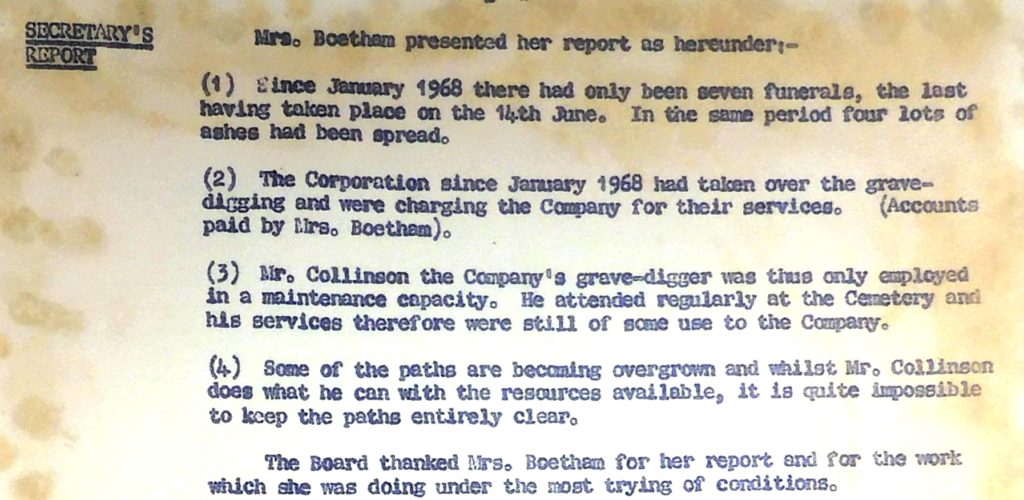

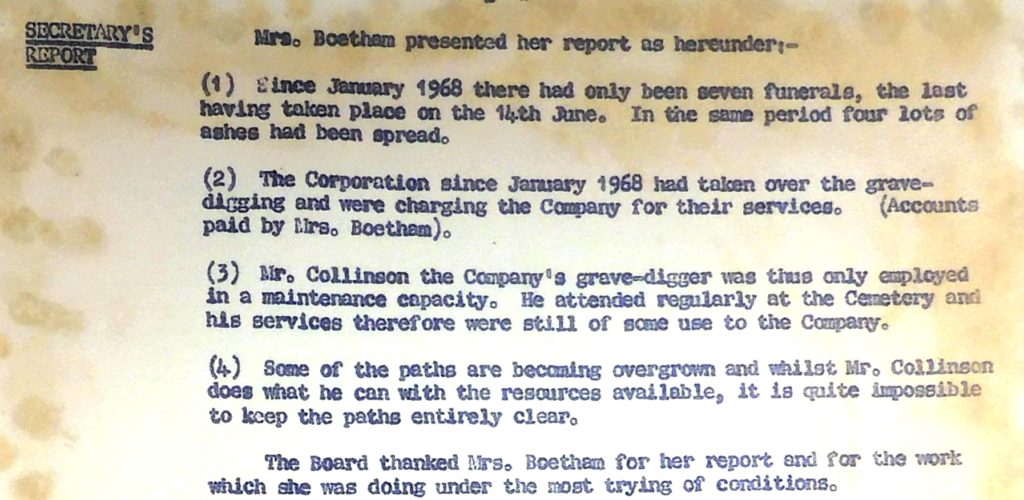

Our final glimpse of this man is from the minutes of the board meeting of the 27th August 1968. The secretary, Ms Boetham, reported to the board the current situation with regard to the maintenance of the cemetery.

Four years later the Company wound itself up. Its a pleasing thought that Charles Collinson was still there, with his spade, when the flag was metaphorically rung down on it.

If he was still there on the Company’s books he would have ben employed by the Company for, at least 61 years and at most 65 years. A considerable amount of time by any standards.

Afterwards

At this time its also conceivable that Charles witnessed, from his bedroom window, as the tractors moved in during 1977. Demolishing in weeks what he’d spent almost his whole working life trying to maintain. I wonder how he felt?

Another bitter pill for him was that when the Hull City Council took over the site no further burials would be permitted. Therefore Charles could not be buried with his wife and son. Charles was to be alone in death too.

Charles died on the 15th December 1979 from bronchial issues. He was cremated. His abode at death was Aneurin Bevan Lodge. He had forsaken Sherwood Avenue after 50 plus years.

Its intriguing to think that I, who began work in Western and HGC in May 1979, may have met this man. If he had been able to pay a visit to his old work place of course. And the likelihood of that, when he was aged 97 years old, is slim.

A silly fancy no doubt, but us hand grave diggers need to stick together. There aren’t many of us left. We really are a dying breed.

Postscript

Unfortunately, the image at the top of this article is not Charles. It is of a grave digger at Mottram Cemetery, pictured at the turn of the 20th century.

There are no images of Charles that I know of. He was just another of the characters who featured in the life of the cemetery who we have no idea of their likeness. These include John Solomon Thompson, the first and best chairman of the Company, and John Shields, the first superintendent of the cemetery, who helped Cuthbert Brodrick lay out the cemetery. So, Charles Collinson is one of the ‘missing’.

But wait a minute! As you may remember when Charles was due to go to Court, the directors of the Company said he’d been employed , in 1938, ‘for well-nigh 30 years’. The trial was in the September so Collinson could have started in employment for the Company during October of 1908 at the earliest.

Here’s an image taken from the Hull Daily Mail of December 1908 at the funeral of a Mr. Moran in Hull General Cemetery. The caption is of gravediggers laying the wreaths on the grave. Is Charles Collinson one of these hazy, fuzzy figures? Well, your guess is as good as mine but let’s hope that it is. If it is we are lucky and if it isn’t, well let’s pretend it is. I think Charles deserves that, don’t you?

Pete Lowden is a member of the Friends of Hull General Cemetery committee which is committed to reclaiming the cemetery and returning it back to a community resource.