This is the concluding part of the story of the Hodsman family. The family that provided the two master stonemasons for the Cemetery. The first part of the story dealt with Peter Hodsman. Stonemason of the Cemetery This second part deals with his son William and the ups and downs of his life.

William Hodsman was born in 1853 in Longton, Staffordshire. We will never know why his family were there but we can have some shrewd guesses. Peter, his father, was a journeyman stonemason. As a journeywoman he would have gone to where the work was no matter the distance. And at this time the Potteries was a booming place for such men as Peter.

The Potteries

Longton is now a part of Stoke-on-Trent. When William was born it was one of the Five Towns made famous by Arnold Bennet’s works. On the Potteries website it is noted that Arnold Bennet compared Longton itself to Hell. That may well have been true but it was a place where Peter’s skills would have been in demand. Skills such as brick-making and stone dressing.

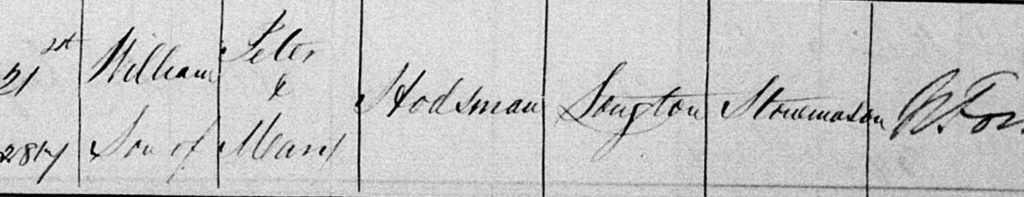

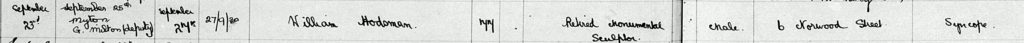

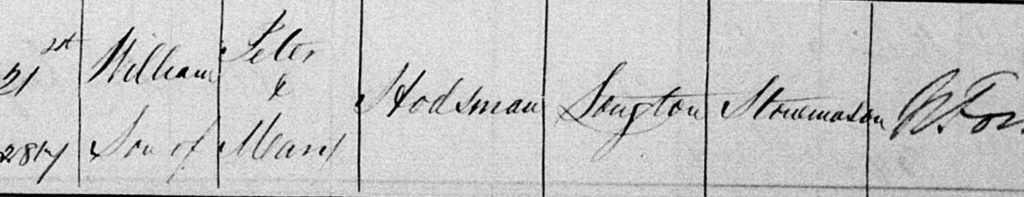

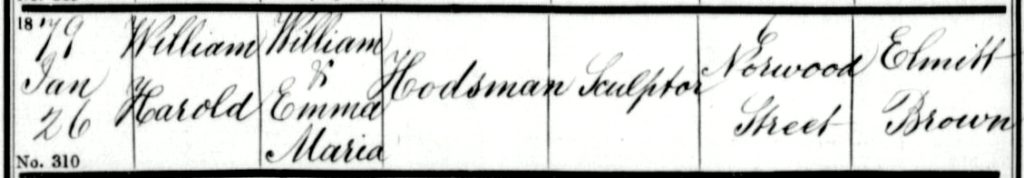

So, William was born in Longton as this parish record shows. He was baptised on the 21st August 1853.

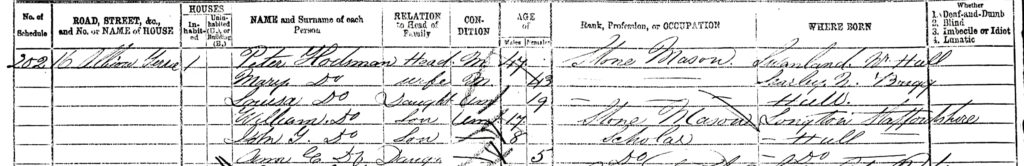

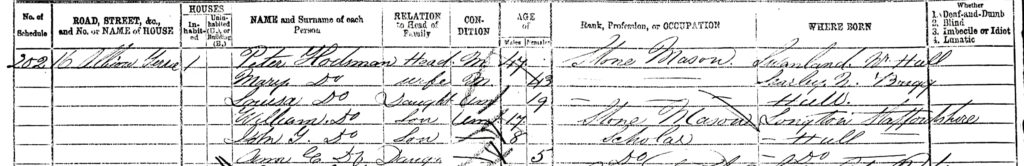

His childhood may have been spent amongst the brick kilns of the Potteries. We have no way of knowing. What we do know is that by the time of the 1861 census the family were back in Hull. The next we know of William after the 1861 census is his introduction to the life of the Hull General Cemetery.

Stonemason’s apprentice

William Hodsman learnt his trade in the Cemetery. We know that his entire working life was spent with the Company. On the 6th August 1868, shortly before his 15th birthday, William was taken on as an apprentice stonemason upon the request of his father Peter. Peter, as we know, was the master foreman of the stonemasons in the cemetery. The Board were dependent upon his skills and valued his opinion. In this case his advice was tinged with nepotism but it was still good advice.

By the time of the 1871 census William is still living with his parents in Albion Terrace, Walmsley Street. He is titled a stonemason.

The Cole family

We now encounter a mystery. Those of you who have dabbled in genealogical waters know what I mean. An aberration that cannot be easily explained. We know that William was employed by the Cemetery Company and had been since 1868. It is extremely unlikely that he would have given up this job.

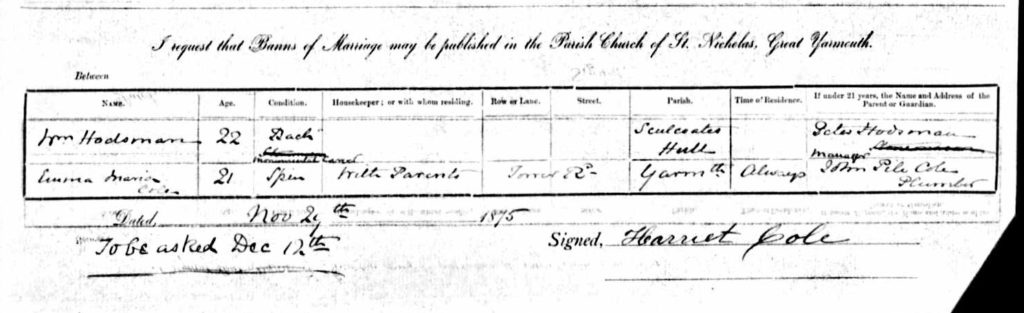

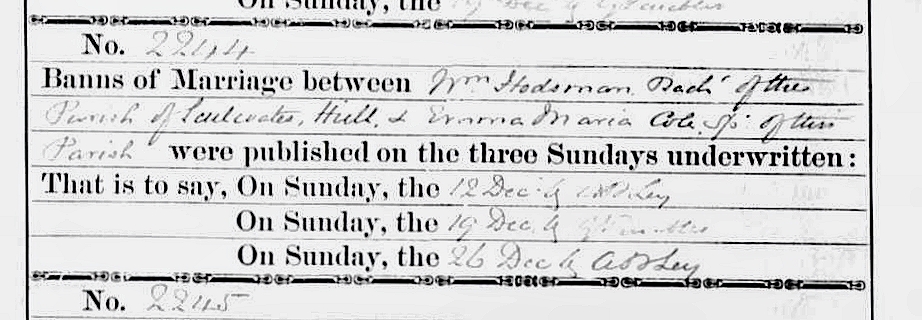

So, him turning up in the announcement of his wedding banns in Great Yarmouth in 1875 is surprising. Of course, it’s not impossible that he travelled to Norfolk and the rail network then was much better than now. Still it is interesting

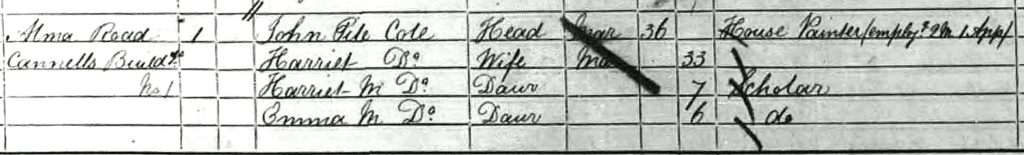

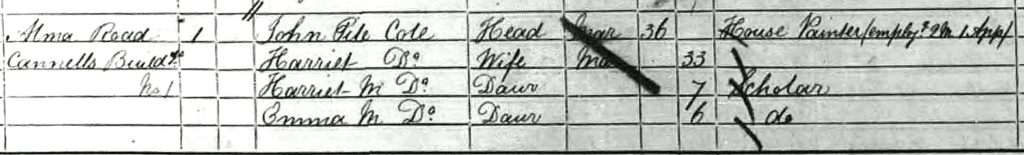

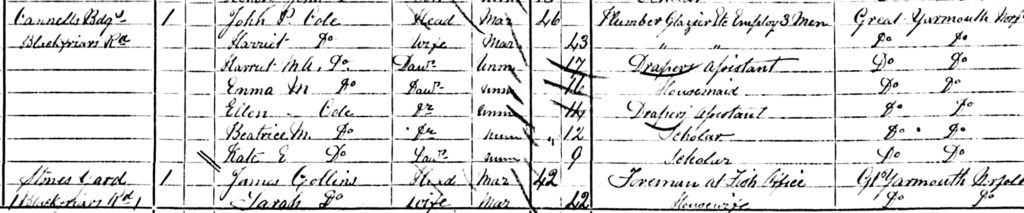

One wonders how William met his future wife, Emma Maria Cole. She was the daughter of John Pilo Cole. Below is the 1861 census on which she appears for the first time.

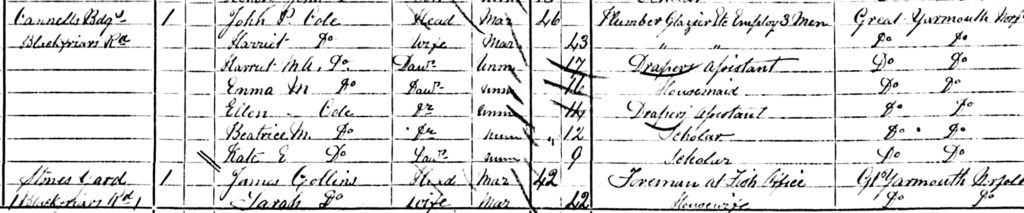

As can be seen John Cole was self-employed as a house painter. Indeed he employed others, nine men and one apprentice.. He would have been one of the lower middle class of the time. By the time of the 1871 census his circumstances appear to have changed. He was still an employer. The workforce was smaller, now only three men.

His trade appeared to have changed too. The enumerator put down on the census form that he was now a plumber and glazier. All of these trades would have been essential during the house building boom of the mid Victorian period. John Cole was probably riding the crest of this wave and was capable of turning his hand to whatever was needed.

That he was also reasonably well off can be deduced by his neighbours in 1871. These were school teachers, publicans, master coopers and foremen. John died in December 1880.

Still a mystery

However we still have no idea how Emma, a Norfolk girl, met with William Hodsman, a lad from Sculcoates. Allow me to romanticise a little. Notice on the above census the address at the bottom of the page. Indeed the premises right next door to the Cole family. ‘Stones Yard’. Now this could be a name derived from someone’s name in the past or it could be a descriptive term for a stone yard.

What about the idea that William, sent by his father as part of his apprenticeship to another stone yard on some errand, met and fell in love with the ‘girl next door’.

I know, I am ‘romancing the stone’ so to speak but we are left with no information as to how this couple met.

Suffice to say that it was a love match. They did not separate until death intervened.

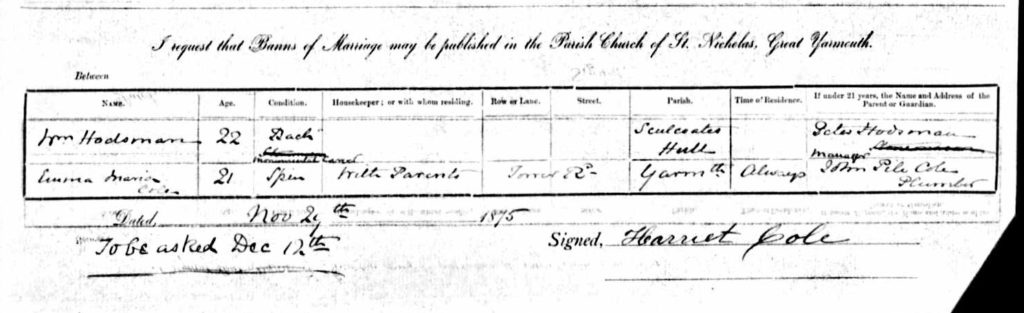

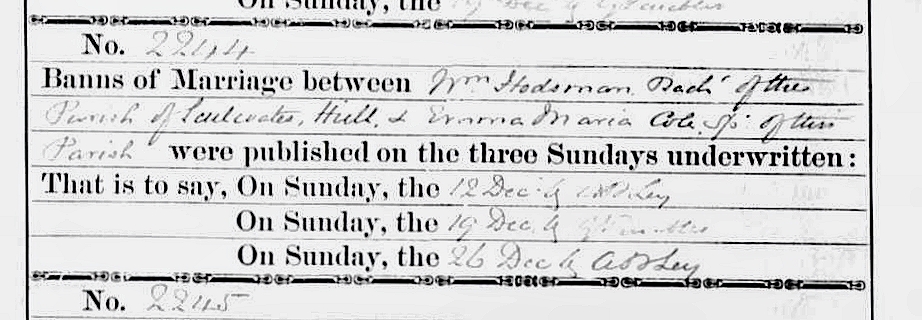

In 1875 the wedding banns were proclaimed. Harriet, Emma’s sister, served notice of them in November 1875

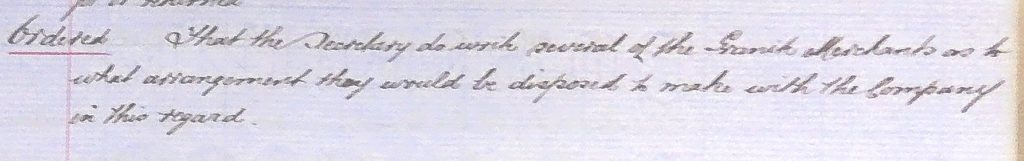

I’d like you to note that William had originally said that his father was a stonemason. It was later changed to ‘manager’. Its also interesting to note that William himself has had ‘stonemason’ crossed out and ‘monumental carver’ place instead. We will see further evidence that William saw himself as more than a stonemason.

The banns were completed by the end of the year and Emma and William were married in 1876.

Back to Hull

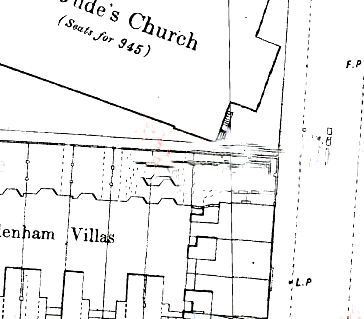

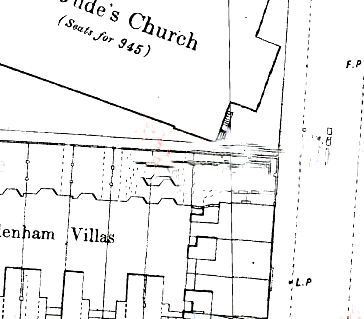

We know the young couple made their home in Hull. The couple lived at 6, Norwood Street for as long as they both lived. The map below shows the right hand side of Norwood Street with St Jude’s Church at the top facing on to Spring Bank. The house at the very bottom of the map is number 6. It was demolished in the late 1970s. The house would have been conveniently situated for them. William was close to his workplace, the Hull General Cemetery, and also close to his father and mother who lived further down Spring Bank in Stanley Street.

A tragedy

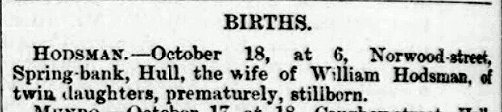

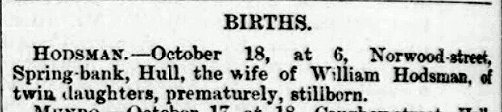

That they lived at this address from such an early date is confirmed by a sad piece of news. The small newspaper item below, of October 1876, imparts a tragedy.

And another mystery

And once again we encounter a mystery. The date given of the tragedy is October 18th yet the newspaper item is dated the 27th of that month. A period of grieving perhaps? Yet, as we know, the family would have wanted this news to be shared with well-wishers and friends.

So why the delay? On top of that is the fact that the stillborn children are not buried in Hull. Their burial did not take place in either Hull General Cemetery, Western Cemetery or Hedon Road Cemetery. Yes, they may have been buried in Sculcoates Cemetery but that is extremely unlikely to say the least.

Did Emma go home to her parents for the latter stage of her pregnancy? It’s a possibility. If so could the children have been born, died and buried in Great Yarmouth? That is a possibility too but as the Great Yarmouth cemetery records are not accessible we cannot check this. No, this is a mystery we will never solve at the moment.

Professional life

We have followed up on William’s personal life without taking into account his professional one. Let’s backtrack a little. In December 1872 the Cemetery Company Board increased his father’s wage and at the same time also increased William’s from 30/- to 35/-.

This was a significant amount for a young man to be earning. Remember he had only joined the Company in the August of 1868, just over three years earlier. Using the ‘measuring worth’ website it’s reasonable to suggest that at its lowest comparative value to today it would be in the region of £136 per week. More likely it would be around £800 per week. As I said a significant sum. Around about £38,000 per annum today.. More than enough to start a family, as William did later on.

On another tangent it must be mentioned that Peter had two sons that survived. The second one, John, was born in 1863. In the August of 1877 Peter applied once again to the Board for this son to become an apprentice and this application was also accepted by the Board.

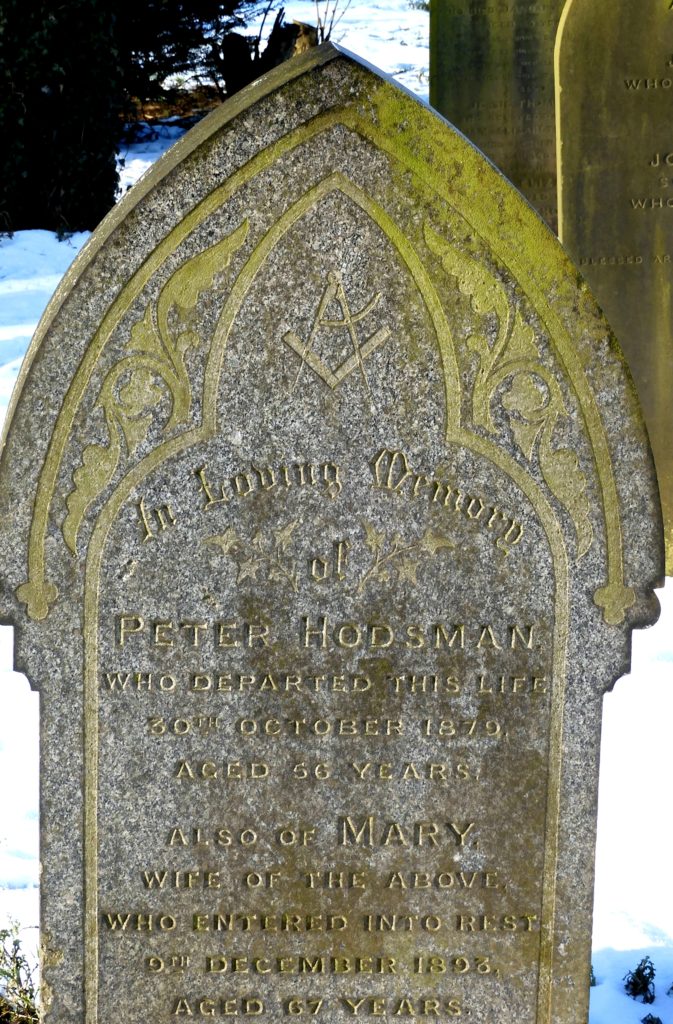

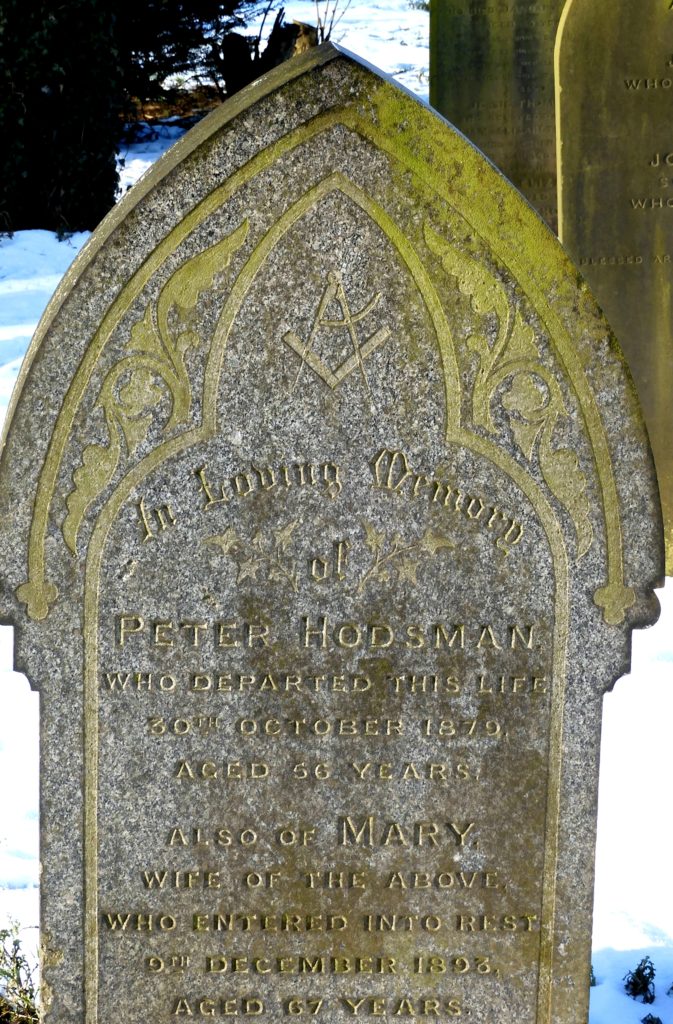

As we found out last month Peter died in 1879. We don’t know if William took his place immediately at the Cemetery but it is likely. William would now be time-served and skilled at the work.

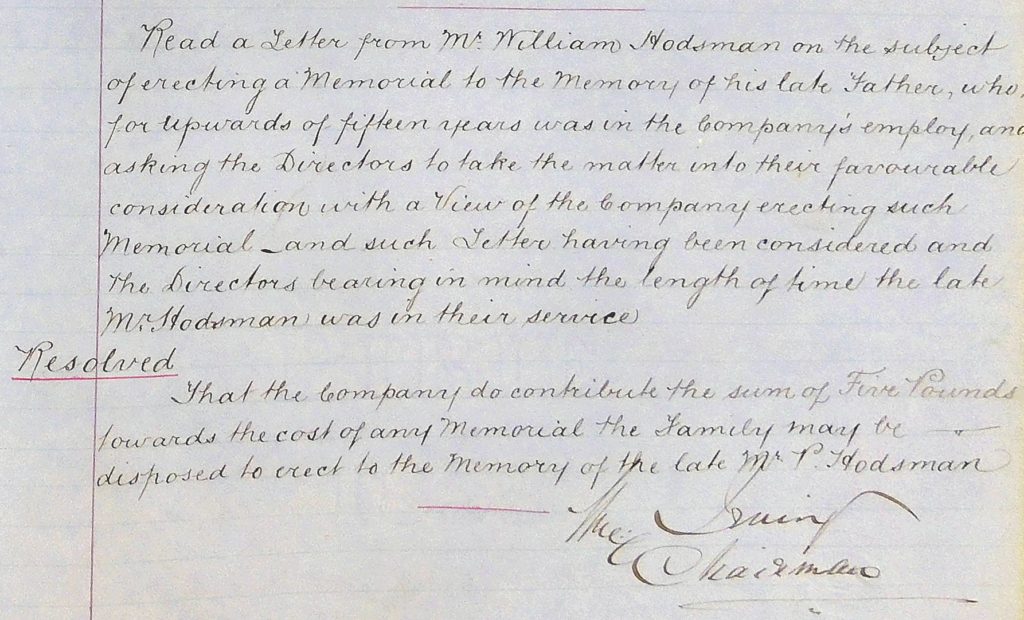

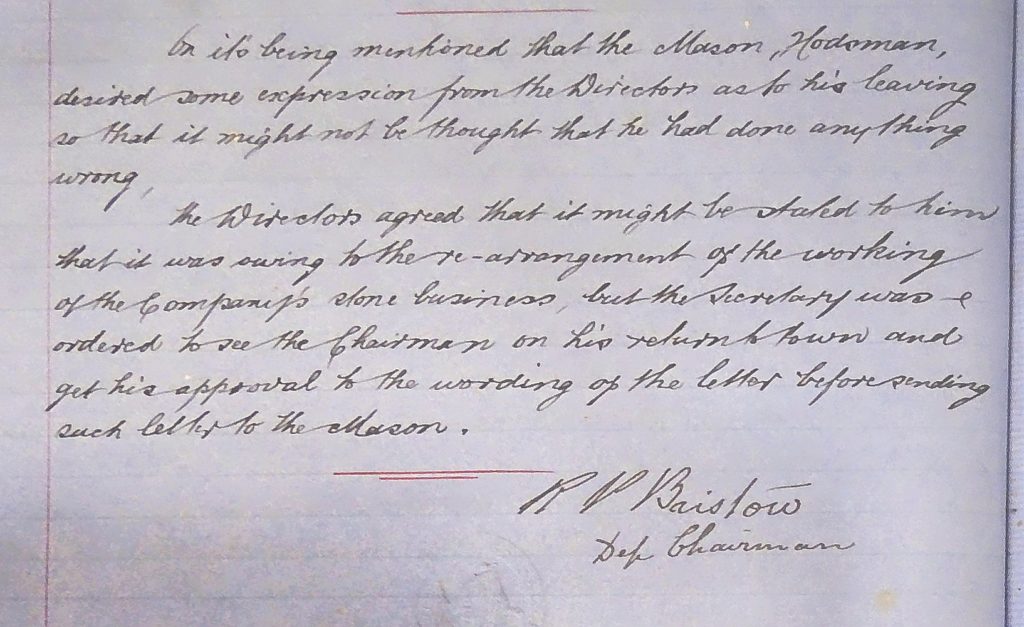

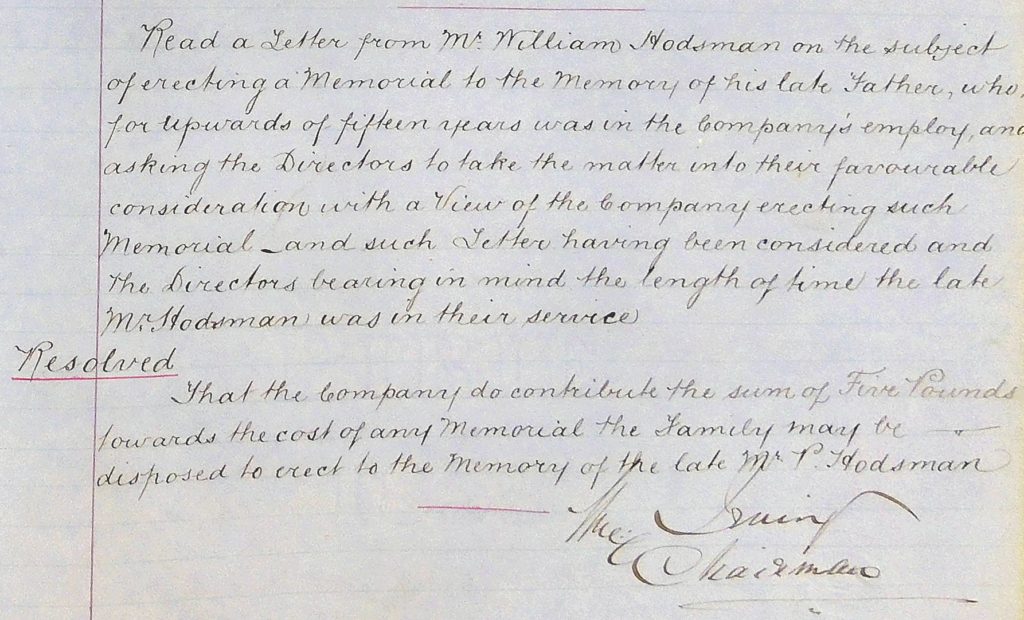

Letter to the Board

In June 1881 William wrote to the Board. His letter was discussed at the following Board meeting.

And that memorial stone still stands in Western Cemetery.

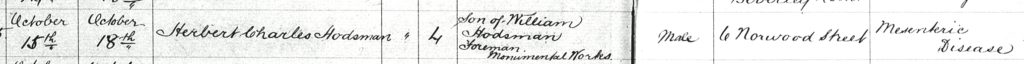

More tragedies

William’s personal life during this period was traumatic.

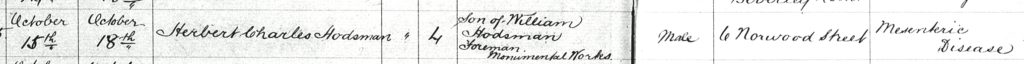

Another son, Herbert, was born in the June1881, the month William was asking for the contribution to his father’s headstone from the Company. Herbert lived just over 4 months and died in the October 1881. The cause of death was listed as mesenteric disease which is a cardio-vascular disease. It is caused by the arteries hardening in the abdomen with a consequent restriction of blood flow. The disease causes severs stomach pains and may come on slowly or rapidly. Even today it can only be diagnosed via ultra-sound What chance of diagnosing it in 1881?

Herbert was buried in the grave next to his grandfather Peter in Western Cemetery. This grave contained Louisa, his aunt, who had committed suicide in 1873, by poisoning herself.

Please note that in the burial record below William is cited as the foreman of the monumental works.

Tragedy struck again in 1886 when the daughter of William and Emma died. Beatrice May had been born in 1880. She died in January 1886 of diphtheria.

She was the first occupant in what was to become the family grave in Hull General Cemetery.

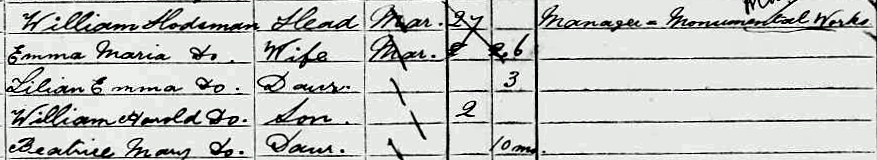

1881

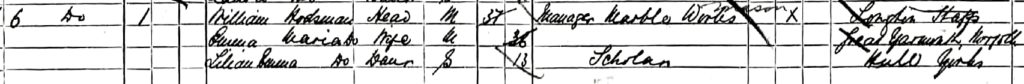

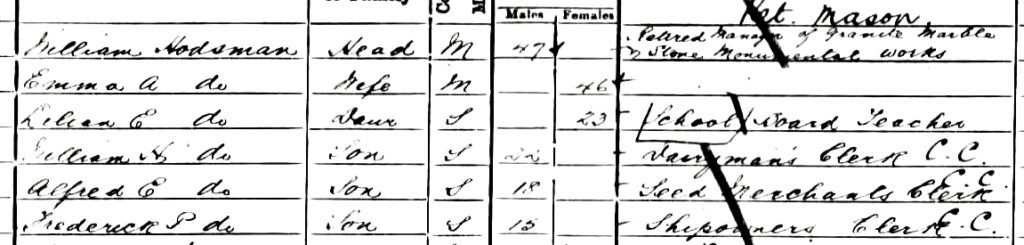

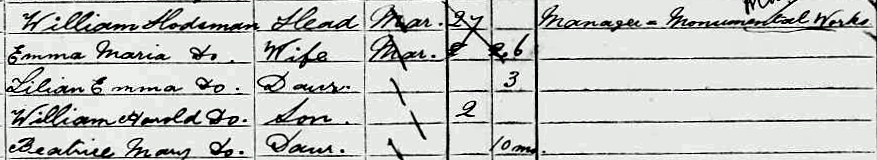

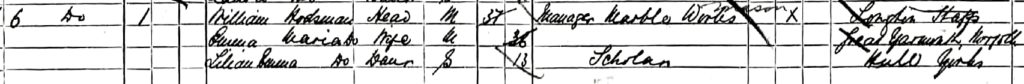

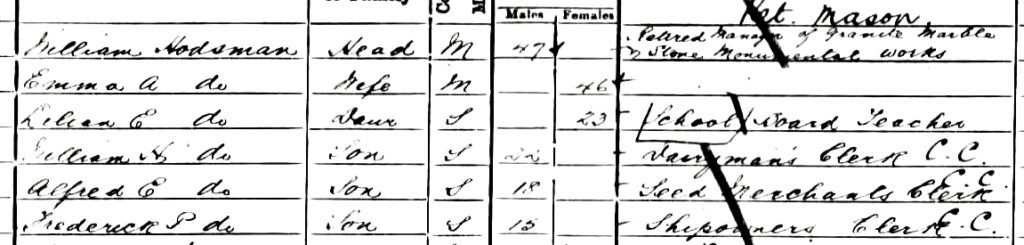

By this time The family of William and Emma consisted of themselves, Lillian Emma born late in 1877, William Harold born in 1879, Albert Ernest, born in 1882 and his brother Frederick Peter Hodsman born the year that Beatrice had died. Let’s look at the 1881 census return for the Hodsman family. William is listed as the manager of the monumental works.

Kingstonia

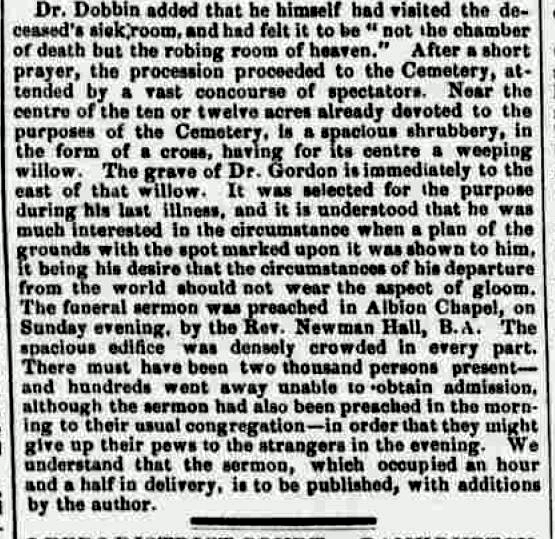

Towards the end of the decade William Hodsman is mentioned in prose. Some of you may be familiar with John Symons. An eminent Hull antiquarian and also a civic leader. He penned many interesting books throughout the latter part of the 19th century. One of these was Kingstonia, a collection of essays, some of which had been published earlier in the Eastern Morning News. One of these essays was entitled ‘ A Visit to the Spring Bank Cemetery’.

Two of my colleagues have recently posted their re-enactment of this ‘visit’ on our Facebook site. It will feature on this site next month. When Mr Symons was undertaking his ramble around the Hull General Cemetery his guide was none other than William Hodsman. As Symons stated,

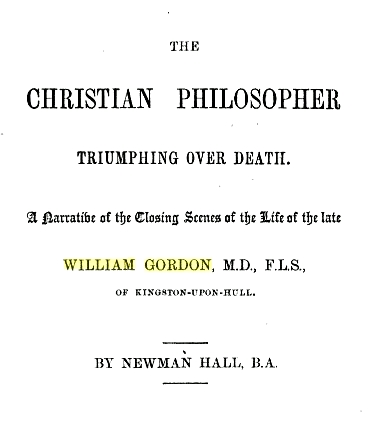

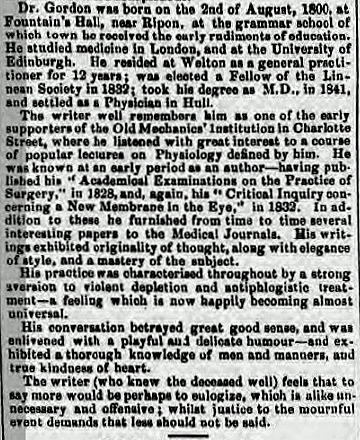

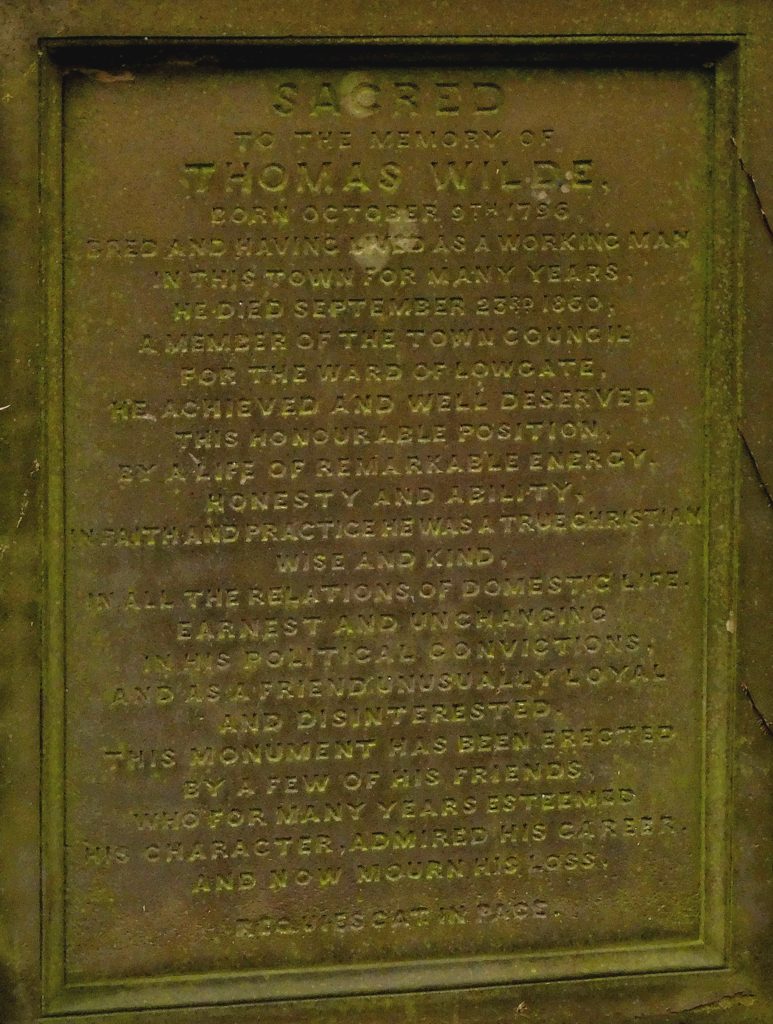

‘Mr Hodsman, the monumental manager of the Cemetery, who accompanied me in my peregrination, pointed out to me, amongst others, the grave – parallel with the monument erected to Dr Gordon – of a man who did useful work for the town.’

As the book was published in 1889, this guided tour would have been earlier, probably 1888.

Financial cut backs

This would have been the same year that finances began to bite the Company even harder and wage cuts were introduced, even to skilled men like William. His wage was reduced from 60/- a week to 52/-.

A considerable reduction. especially as at the next year’s AGM in February 1889 the shareholders voted themselves a dividend on their shares of 16/- in the pound PLUS a 2/6d bonus. By the August of 1889 further reductions in wages were introduced. William’s wage was reduced from 52/- to 45/- in summer and 40/- in the winter!

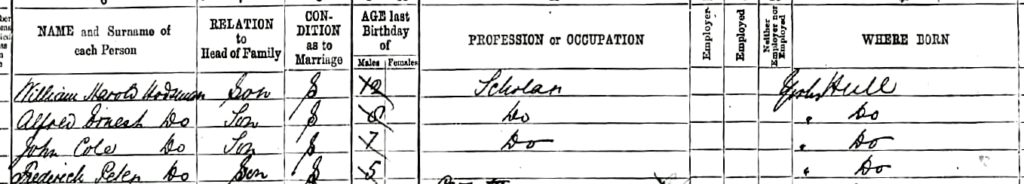

This was problematic for William as by the 1891 census his family had grown.

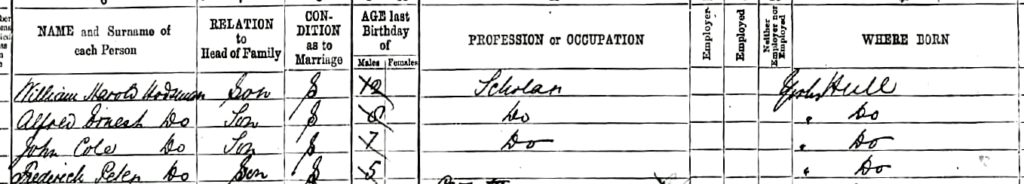

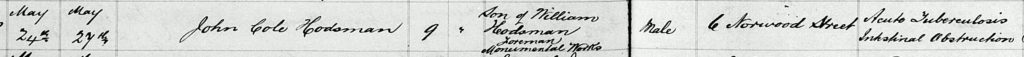

He now had four sons and one daughter. Times were challenging. And tragedy was never far way too. John Cole died that spring.

More cut backs

William was not the only one affected by these changing times. At the AGM in February 1892, after voting themselves another 14/- dividend, the directors informed their fellow shareholders that,

‘The directors would remark that they continue to bear in mind the necessity for every possible economy in the working of the company and they have lost no opportunity of urging this on the company’s employees. They are therefore glad to report that by the appointment of Mr Kelly at a salary of £120 per annum a substantial saving to the company will be effected.’

Michael Kelly had become the new cemetery superintendent plus also the Company secretary. I’m pretty sure that one of his first jobs assigned to him was to look for places where expenditure could be trimmed. By the April he had found something.

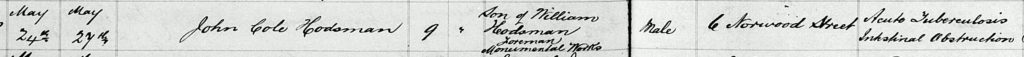

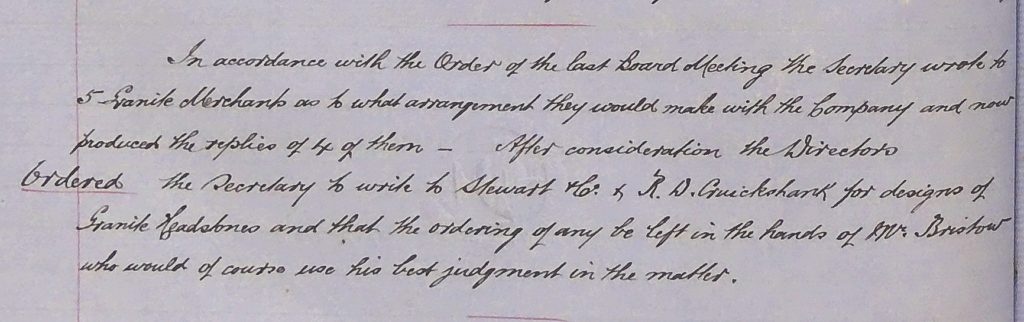

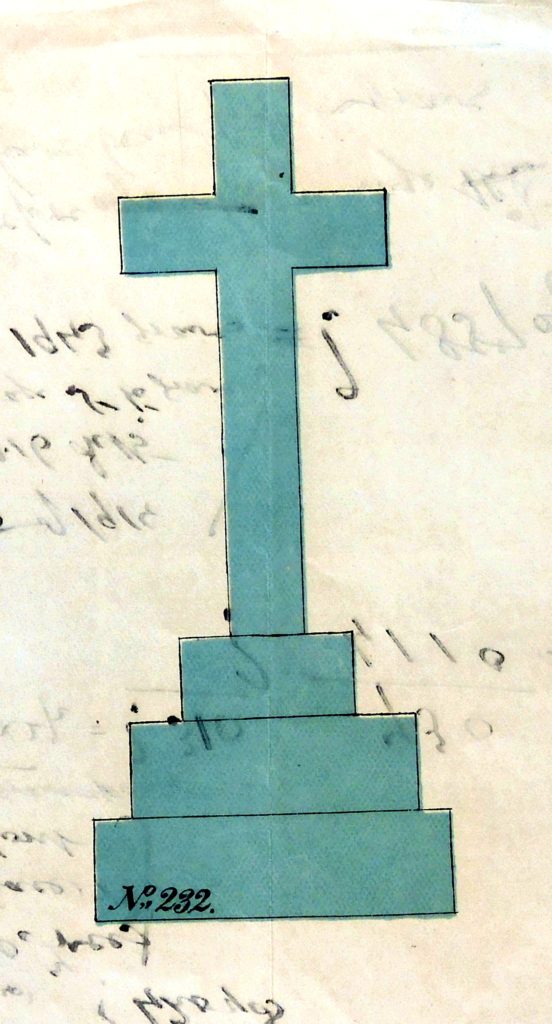

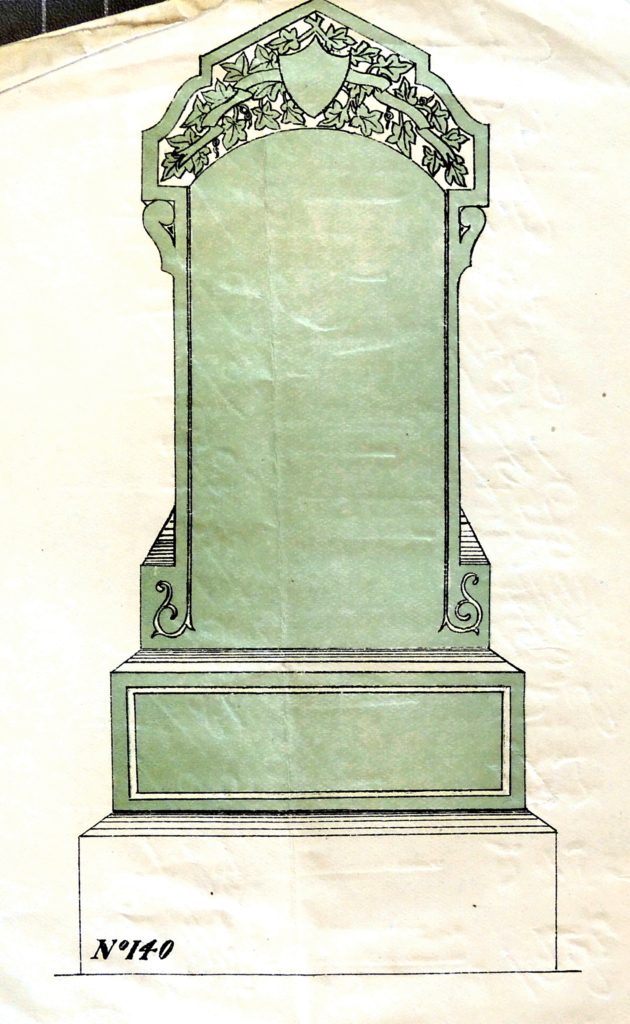

One of the features of the Company’s stone working had been to have an amount of stone on stock that could be worked from scratch. Kelly put forward the idea that this way of working could be dispensed with. Instead of working the stone to different designs he suggested buying in designs and simply lettering them. Needless to say, the directors thought this was a great plan. They directed him to enquire of stone masons in the area if they could supply these ‘off the peg’ stones.

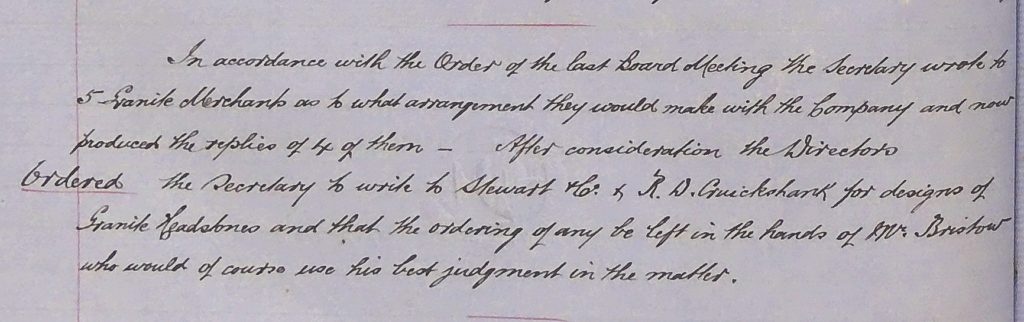

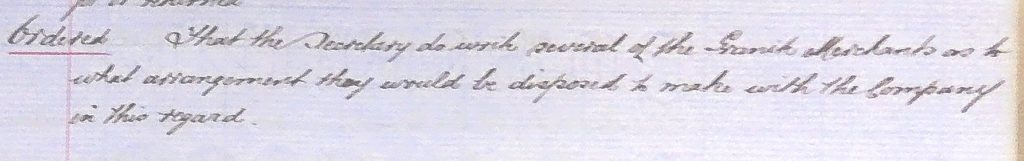

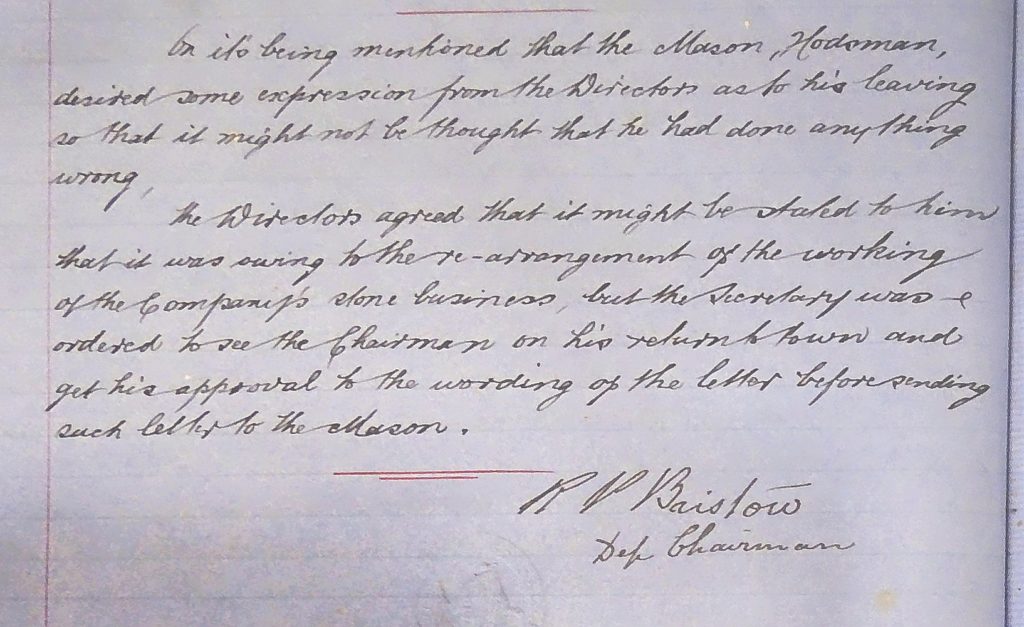

The next month Kelly informed the Board that,

The end of the work of the stone mason

With this decision the Company turned its back upon its stone working business. The very business that the Company had insisted keeping when in serious discussion over the sale of the Cemetery to the Corporation in the 1850s. It’s adherence to a ‘strong’ line on this point meant that those negotiations collapsed.

And now it threw it away in its desire to keep paying over the odds to its shareholders. Whilst desperately seeking cutbacks in expenditure from any and every source other than that. I’ve said this before in talks about the Cemetery but the Board were dreadful managers of this business. Tt is a wonder that it survived as long as it did.

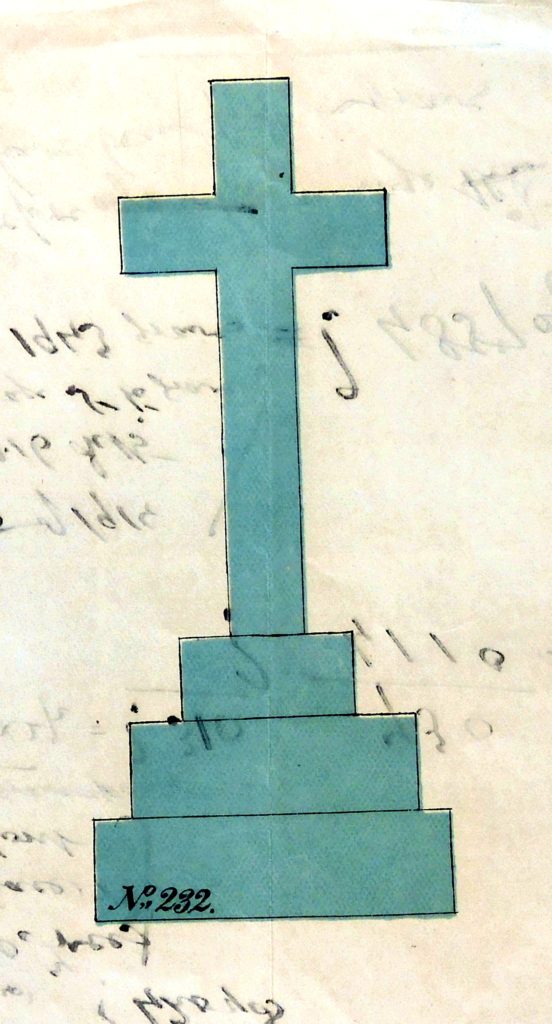

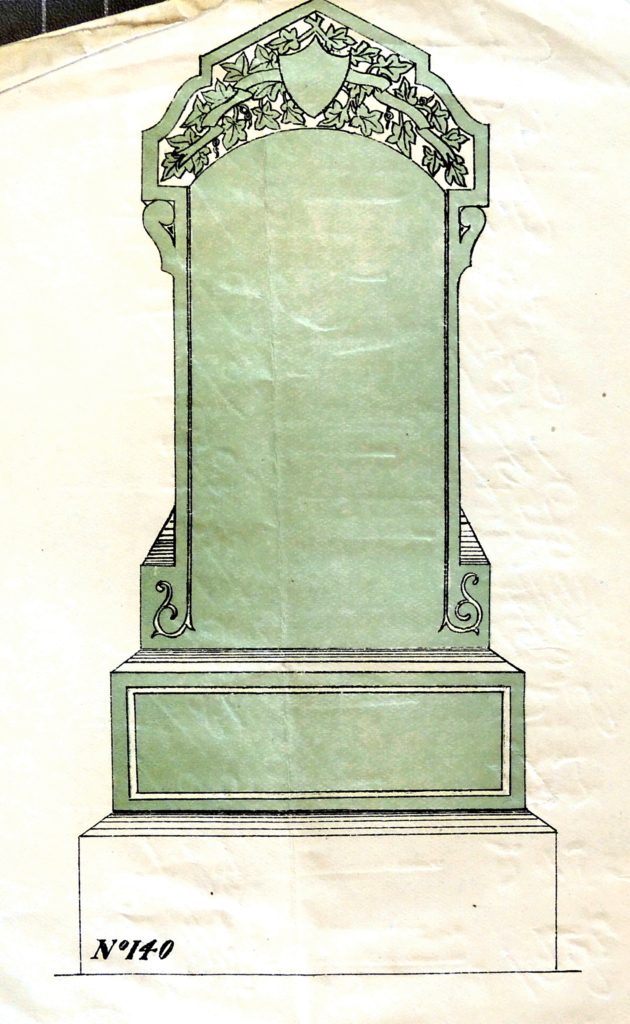

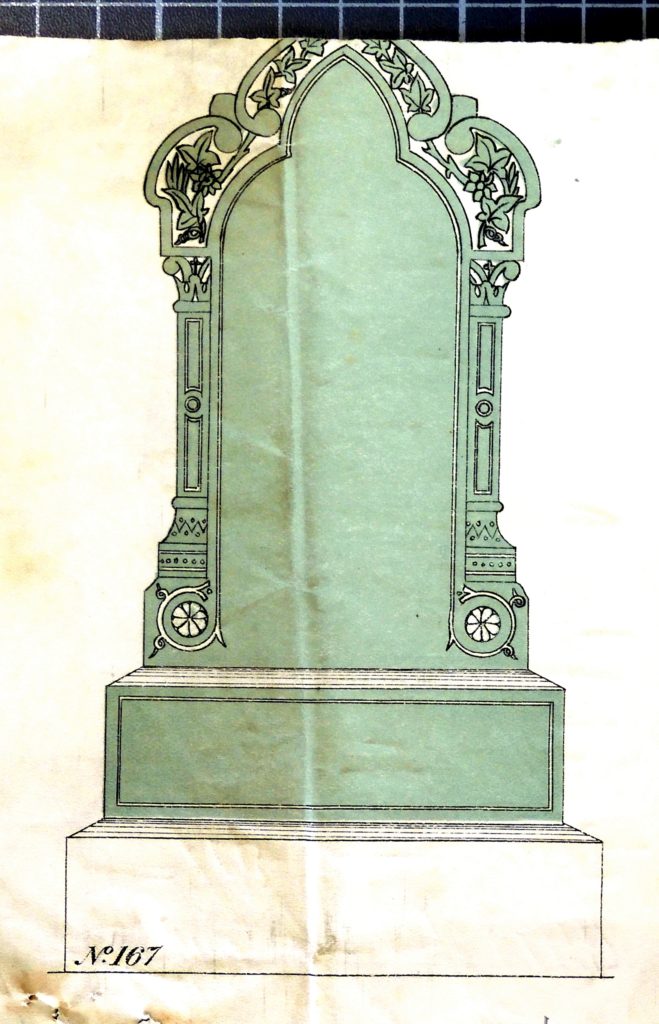

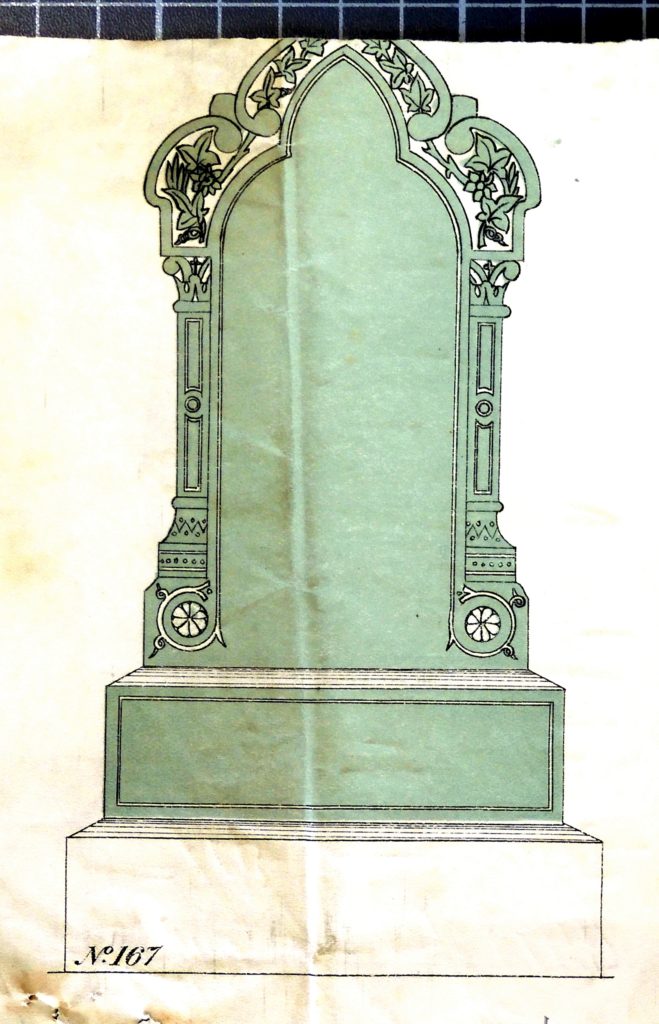

Whilst researching the Cemetery I came across a number of headstone design images, numbered as if from a catalogue. Michael Kelly had used the backs of them to make notes. these images had survived strangely enough when more important material was lost.

Here’s a few of them and understand that you are looking at evidence of what probably destroyed the Hull General Cemetery memorial business.

Meanwhile William Hodsman was not a fool. He would not have been foolish enough to recognise which way the wind was blowing and how it could effect him. We have no evidence that he took any steps to secure his own position except for one, which we’ll come to later.

Changes to the workforce

In case you are wondering it was not only the stone work side of the Cemetery business that was being curtailed.

In February 1895 George Ingleby, the gardener and the foreman of the gravediggers gave in his notice. What Ingleby did not know when he resigned was that at the previous Board meeting it was decided to dispense with his services. At the same meeting it was decide to reduce Hodsman’s wages once again. This time the reduction proposed would be from 45/- a week in the summer and 40/- in the winter to 40/- all year round. In the space of six years William was expected to take a drop in wages of 33% whilst he would have known that the shareholders were effectively taking money straight out of the till.

William countered the offer from the Board. He,

had asked that the directors might kindly consider whether they could not give him 2 guineas a week for say a year and see how it things went on and consider the matter again at the end of that time’

They agreed.

Wages versus dividends

At the AGM later that month the wages of all the staff of the Cemetery was just under £622. The amount paid out in dividends was £550.

Later that year the greenhouse was to be sold to the Corporation who offered £20 for it. Due to the bad feeling between the two parties this deal fell though. Eventually the greenhouse was sold at auction and netted just over £16. Yet another loss for the company.

In the April of 1897 the Company decided to dispense with William Hodsman. William was ready for this. He asked for a reference.

We, of course, do not know whether he managed to get one. It’s unlikely the Company would have refused However, if he did not get one I’m certain that his good name had gone before him.

1901 and beyond

By the time of the 1901 census we see William apparently in good heart. He was cited as a ‘retired manager of granite, marble and stone monumental works’. A young age to retire at in those times but the 1911 census shows the same inscription. Maybe, when times were good William was careful with his money. Maybe he saw the writing on the wall in the 1890s and kept on being careful. I also suspect that he worked occasionally as a freelance worker. His work was well known in the town and there were many monumental masonries than today.

Of note in the 1901 census return is the occupation of his daughter Lillian Emma.

She was now a school board teacher. Some 50 years earlier her grandfather had attended a public meeting to vote on the rapid introduction of secular education into Hull. One gets the feeling that he would have been proud of her choice of occupation. The other members of the family are all in secure, white collar jobs. Not for them the wet mornings in the Cemetery trying to erect a headstone that constantly slipped from the wet harness around it or the horse moved at the wrong time.

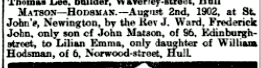

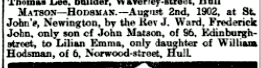

In 1902 there was more joy. Lillian married. The boy she married strangely had the grave just behind her grandfather’s. Did they meet whilst tending their respective family members’ graves. I’ll leave that to your imagination but that plot could surely have come out of a Charles Dickens’ novel.

By 1911 these two were living comfortably at 136, De La Pole Avenue. He was now a solicitor’s clerk and sadly, she had left the teaching profession. There were no children.

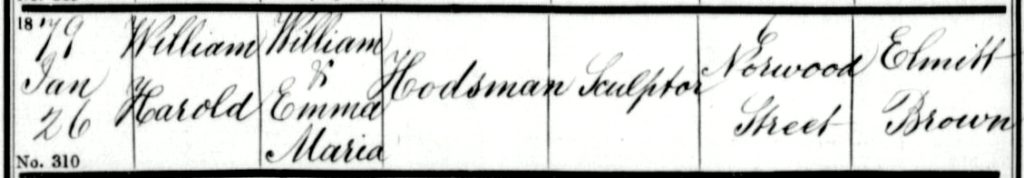

William Harold

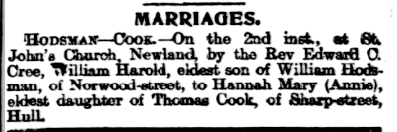

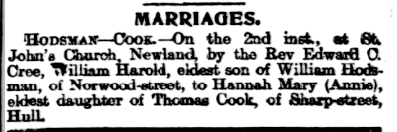

In 1903 William’s eldest son, William Harold, married a lady called Hannah Mary Cook. William Harold had been born in 1879 and was baptised at St. Jude’s, the church on Spring bank at the top of Norwood Street.

This entry caused some confusion. Not only for me but for the recorder. The occupation and the address are transposed and placed in the wrong columns to all the rest on the page! It’s telling isn’t it that William called himself a sculptor rather than a stonemason.

The wedding took place at St John’s in Newland

By 1911 William Harold had moved to Scunthorpe and was a Milk Dealer. Self-employed he now had four children. Once again William probably could be proud that another of his children was not freezing in the Cemetery trying to make a living.

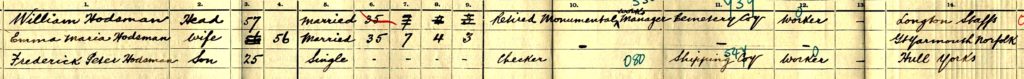

1911 and Frederick

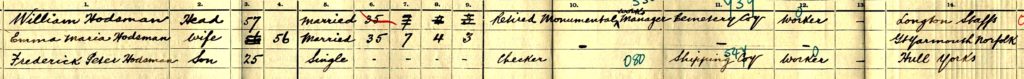

The 1911 census shows us that William and Emma Maria were living at 6, Norwood Street and that the other occupant was Frederick Peter.

As you can see he was a checker at a shipping company. William still basked in the glory of retirement and his last employer listed was the Cemetery Company. Two years later this happy situation was to change dramatically.

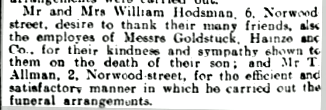

In 1913 William and Emma lost this child.

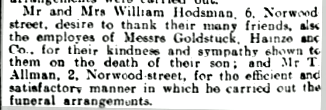

He died from congestion of the lungs. He was 28 years old. His grieving parents placed a notice in the newspaper. One wonders what emotion and hurt this simple notice hid.

The end of William and Emma

In 1928 Emma Maria passed away. The cause of death was a mixture of thrombosis of the the left femoral artery and gangrene of her left foot. She was buried in the family plot in Hull General Cemetery.

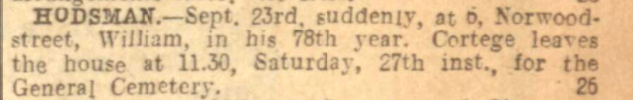

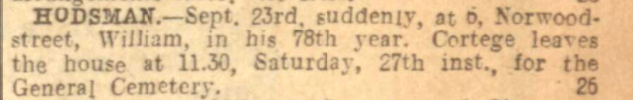

Two years later William himself died. The cause of death was syncope, or an episode of fainting due to a loss of blood pressure. One has to wonder whether he felt that life was not worth considering after Emma had died.

John Hodsman

John, his younger bother who was also taken as an apprentice stonemason by the Company, died in 1945. He had worked at the cemetery but this relationship, like his brother’s, had ended in the 1890s. After leaving the Cemetery he had become a gas fitter and he does not play any part in the story of the Cemetery.

William’s burial and memorial

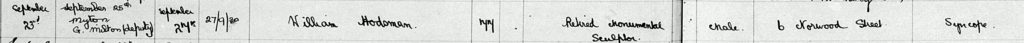

William’s burial record is below.

Now, one would expect a monumental stone mason to have a monument on his family’s grave. And yes, there was one once. And yes, you know where I’m going with this don’t you? Strangely you’d be wrong.

My research has shown that it survived the disaster that was the 1977 / 78 clearance. What it didn’t survive was the neglect of recent years.

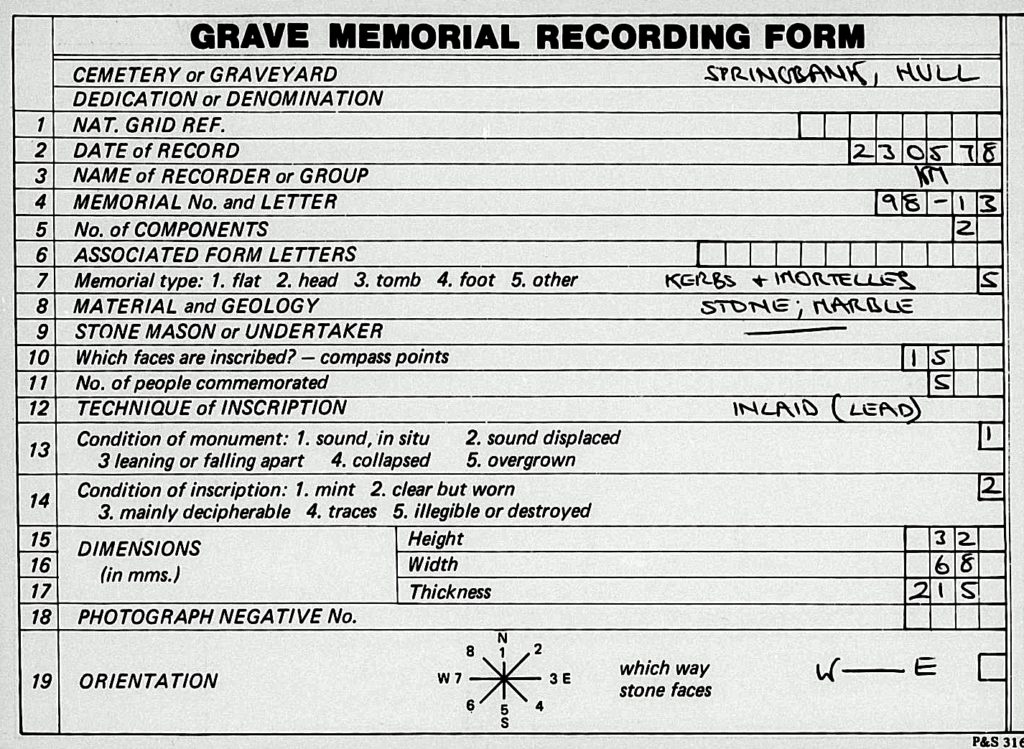

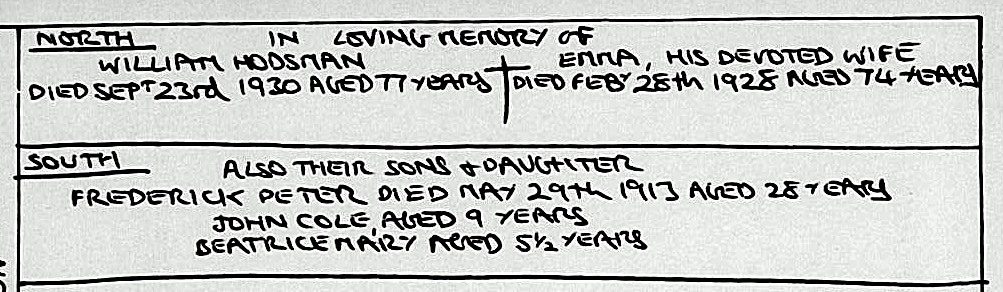

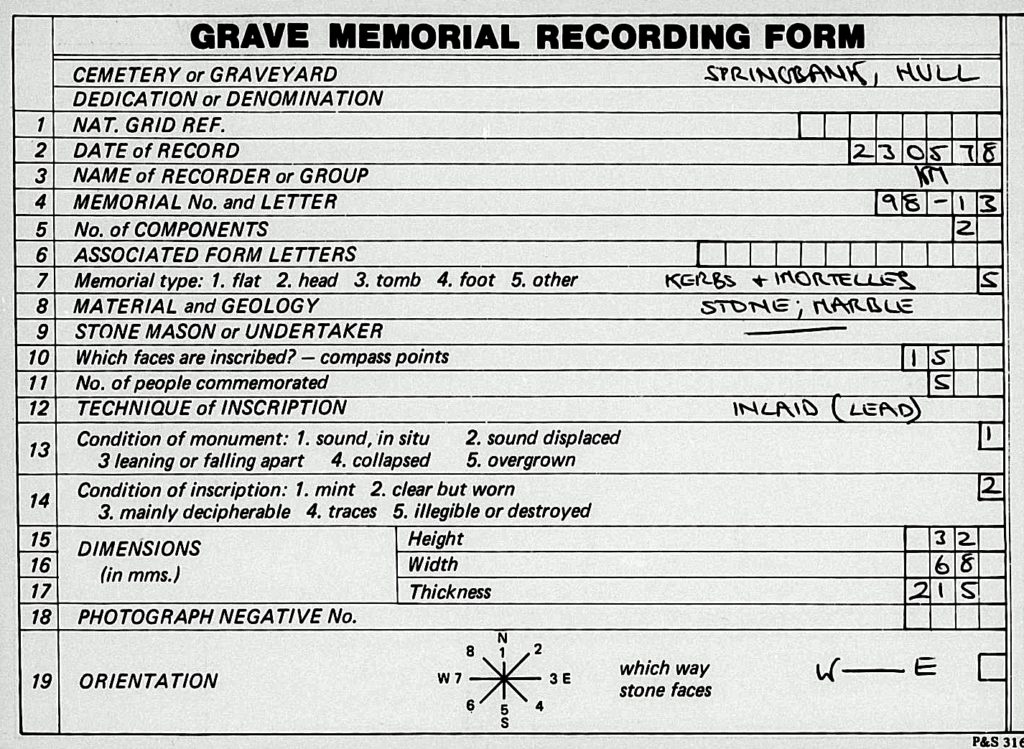

Here’s a copy of the memorial recording team in the 70’s As you can see the stone was sound and in good order.

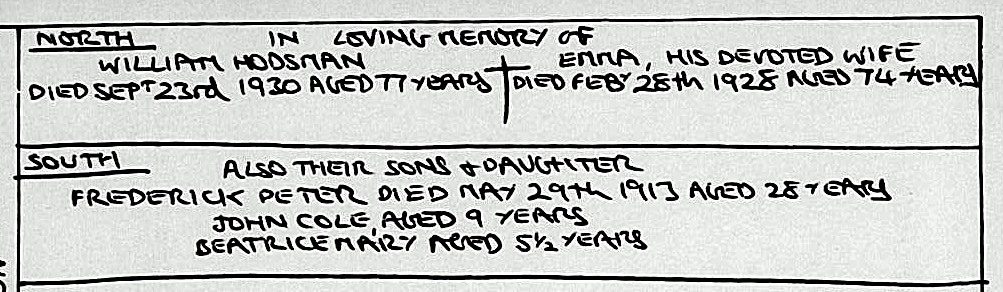

And here’s the record of the inscriptions that were on the stone.

That was then. Here’s the stone today. Well at least the only part that can be seen.

And here’s what destroyed it.

So, the monument to a monumental mason, who probably carved some of the beautiful pieces of art in the cemetery, has almost gone. Lost beneath what, in my uncharitable moments, I would designate a weed. A sycamore. The curse of all Victorian cemeteries.

Its too late for the Hodsman monument but surely this is food for thought. We neglect these things for a short time and when we turn around to find them again they’re gone. Just like William’s monument A lesson there for us all. Hodsman’s monument won’t come back. It’s gone forever. A valuable heritage asset of the history of Hull destroyed. The sycamore, on the other hand, no doubt has spread its progeny far and wide. So, it is not irreplaceable like the monument. In fact it is very common and quite replaceable. And yet….

The other monuments in the cemetery must be better protected. And that protection has to start now. And with you and me and all of us.

Pete Lowden is a member of the Friends of Hull General Cemetery committee which is committed to reclaiming the cemetery and returning it back to a community resource.