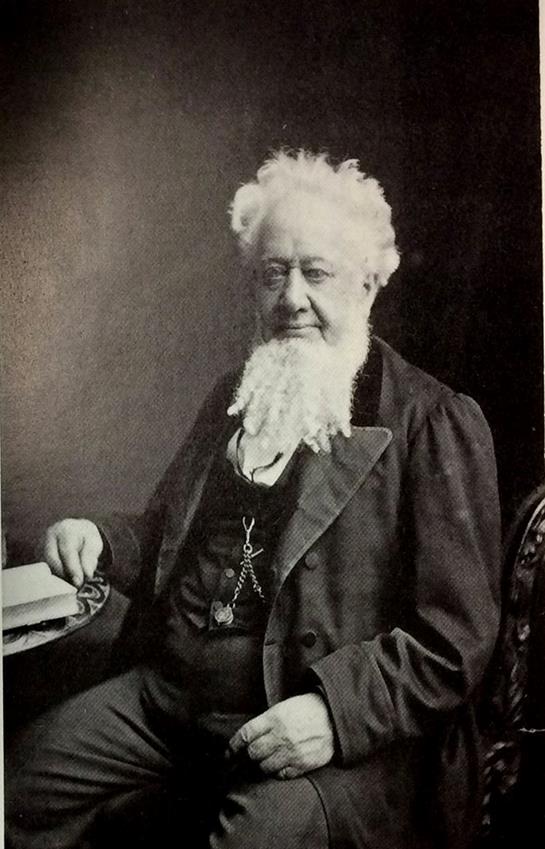

3. Thomas Wilson

He was born in Hull in 1792, the son of a lighterman, David Wilson & his wife Elizabeth Gray.

Thomas married Susannah West, the daughter of a Hull wine merchant, and they had 15 children. He was apprenticed in the counting house of a Hull merchant, and after working in the Sheffield steel industry for a few years he formed a partnership with Newcastle merchant, John Beckington. The company started dealing in iron ore with Sweden, sending consignments of the high grade ore from his yard at Garrison Side to Sheffield for smelting.

After experiencing problems with the Swedish shipping service, Thomas Wilson & his partner began chartering sail powered packet boats between Hull & Gothenburg, taking passengers as well as cargo. Wilson & Beckington then began using the new, much faster steam ships on the Gothenburg and later Norway routes. By 1840 the partnership broke up and after a short period as Wilson Hudson & Co, Thomas Wison continued on his own, expanding his iron ore trade with Sweden.

Business expanded

His business rapidly expanded and four of his sons, David, John, Charles Henry and Arthur joined the company. David, who was unmarried and lived at The Bungalow, Cottingham, later left to run his mother’s wine business. John also left to work in Sweden and became a naturalized Swede, leaving the running of the business to Charles Henry and Arthur.

In the mid 19th century the port of Hull was booming, resulting in the opening of three new docks. In the 1850’s, Thos. Wilson & Sons commissioned the construction of several steam boats from Earle’s ship yard on Hedon Road. It was at this time that they started the practice of naming them with names ending in ‘o’ with green hulls and red funnels. (Wilson’s parrots)

Thomas and his wife lived at the relatively modest Park House in Cottingham. He was a typical blunt Yorkshireman with a reputation for ruthlessness. However, he was a great philanthropist and contributed generously to many welfare projects in Hull. These included the Orphan Homes on Spring Bank and a house for fallen women in Nile Street.

Stepping back

Although Thomas kept an active role in the business, it was effectively being run by Charles Henry and Arthur. Charles later became Lord Nunburnholme and lived at Warter. Arthur lived at Tranby Croft in Anlaby, the scene of the famous ‘Baccarat Scandal’ involving the future King Edward VII.

Thomas died of a stroke at his home in June 1869, aged 77.

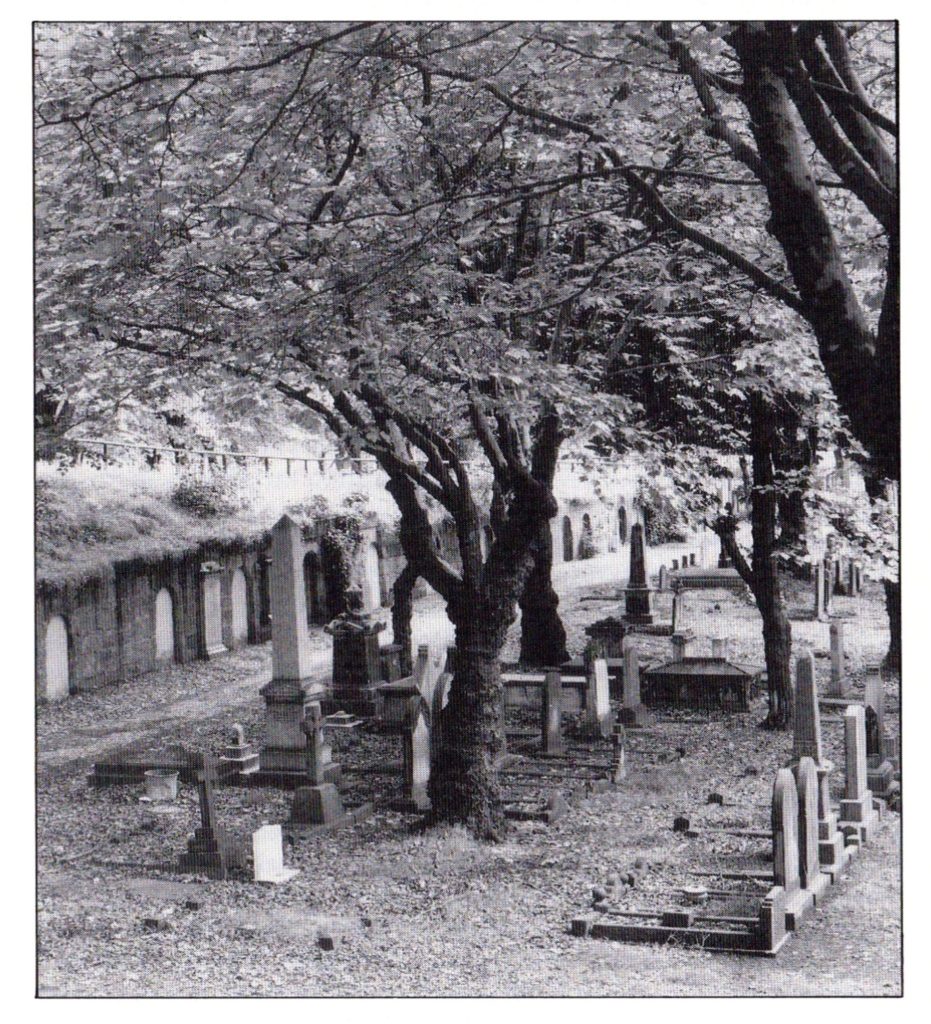

He was one of the first Hull businessmen to be buried in the new Hull General Cemetery. The cortege slowly travelled from Cottingham. A group of Wilson employees joined the cortege on Beverley Road. This was later followed by a contingent from Earles’ shipyard, and the orphans from Spring Bank Orphanage joining in. By the time the cortege reached the cemetery gates there were 57 carriages and a crowd of 1500 persons..

After the death of Charles Henry (1907) and Arthur (1909) Wilson’s were purchased by Sir John Ellerman, becoming the Ellerman Wilson Line, one of the largest shipping lines in the world. However, the company lost many vessels in WWI, and as the shipping industry evolved it lead to a rapid decline of the company, eventually ceasing the shipping business in the 1973.

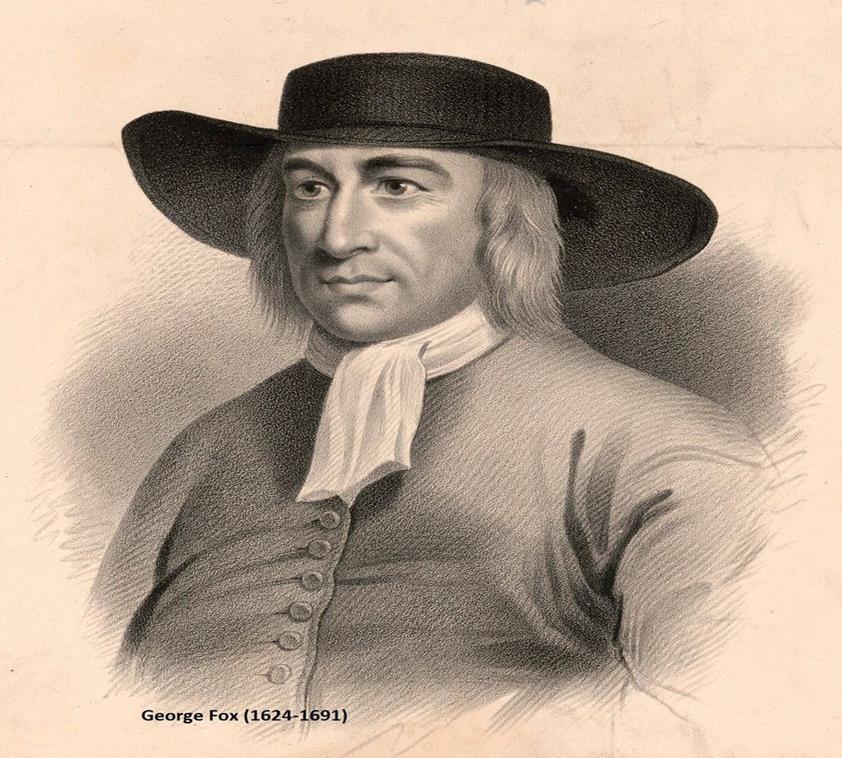

4. Quaker Burial Ground

In 1672, Hull merchant, and a member of the Society of Friends (Quakers), Anthony Wells purchased a half acre site called Sutton Burying Ground as a burial ground for him, and his fellow believers, later becoming part of Hodgson St, off Cleveland St.

It remained a Quaker burial ground until it was forced to close in 1856. The previous year the Society of Friends had purchased a plot in Hull General Cemetery for £100. This had a 999 year lease. This lease remains to this day, and is known as the Quaker’s Burial Ground.

The Society of Friends gifted the old site to Hull Corporation in the 1890’s with a proviso that it could not be built upon. The site was developed into a children’s playground in the early 20th century, (see image above), but after the houses were demolished in the 1960’s/70’s, it became redundant.

The Removal of the Memorial Stones

In 1973, the memorial stones, including the original stone of Anthony Wells’ wife Elizabeth, and those that had been mounted in the brick piers of the old burying ground, were removed and placed in Hull General Cemetery. They still remain there to this day, and are laid flat in a tidy group. NO PHOTO

Many local Quaker industrialists have graves in the Burial Ground, including members of the Reckitt, Priestman and Good families.

5. John Fountain

John Fountain was born in Hull in 1802 and was baptised at Holy Trinity on 20 September the same year. He was a fruit merchant trading from premises in the old town.

He married Sarah Thomas at Holy Trinity on 17 August 1825 and had a daughter, Eliza Ann. She married ship captain Robert Crow Gleadow in 1854.

The family lived at 7 Coburg Terrace on Anlaby Road next door to tannery owner Thomas Hall Holmes, before moving to nearby 3 Balmoral Terrace. John remained there for the rest of his life.

Civic duties

John became an Alderman of Hull and was actively involved in charitable works. This work included being the vice president of the Training ship Southampton, Chairman of the Hull Infirmary Board and Member of the Lodge of Druids.

He was the Governor of the Hull Incorporation of the Poor at the Hull Workhouse on Anlaby Road, for 21 years and saw many changes there.

He died of old age on 15 May 1887 aged 84, and was, according to his wishes, buried in the Workhouse Section of the cemetery amongst the beloved poor people of Hull. His grave is marked with an obelisk and his wife Sarah and daughter Eliza are buried in the same grave.

Fountain Street and Fountain Road are named after him.

6. The Workhouse Area

The workhouse area of the cemetery is a 1 acre area to the west of the cemetery. It contains the graves of approx. 10,000 people who were buried in the cemetery. Hull General Cemetery Company had an arrangement with the Hull Workhouse on Anlaby Road that they would provide a simple coffin and respectfully bury any inmates who had died in the Workhouse.

The graves are public graves with no formal headstone or markings. The three exceptions are the graves of John Fountain and his employees at the Workhouse, James Myers, the workhouse joiner and his wife Ellen, John Vickers, Master of the Workhouse and his wife Margaret, John Coulson Jackson, Workhouse Messenger

Their graves are located close to John Fountain’s monument.

Plaque commemorating the 10,000 Workhouse burials.

There is also a Commonwealth War Grave located in this area, that of Sgt Herbert John Alexander of 7th Battalion, East Yorkshire Regiment.

The Workhouse Graves of Hull General Cemetery

7. Johnson Obelisk

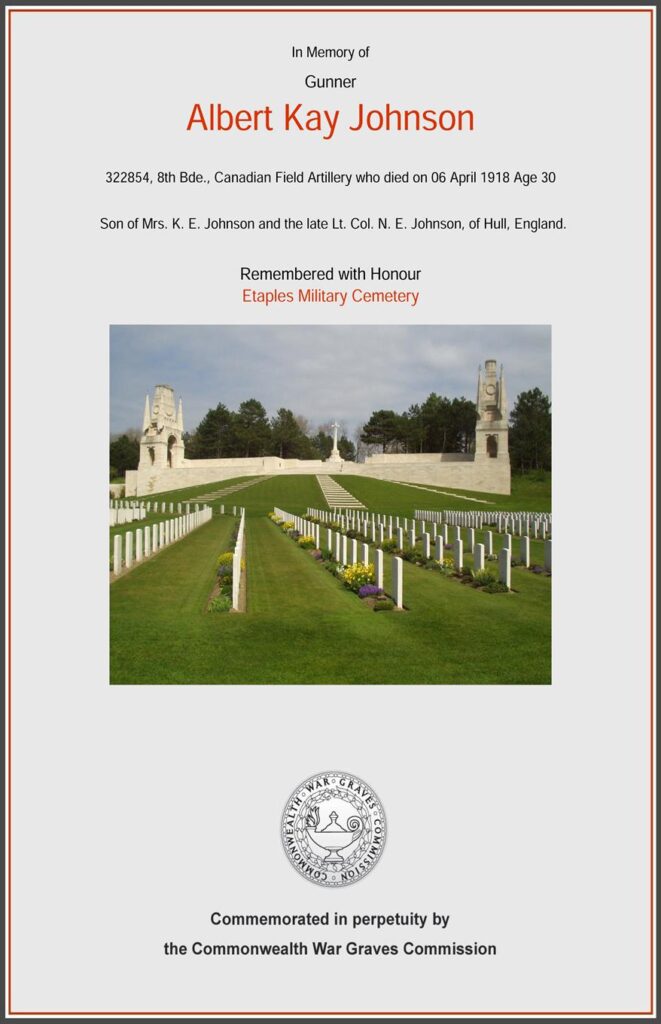

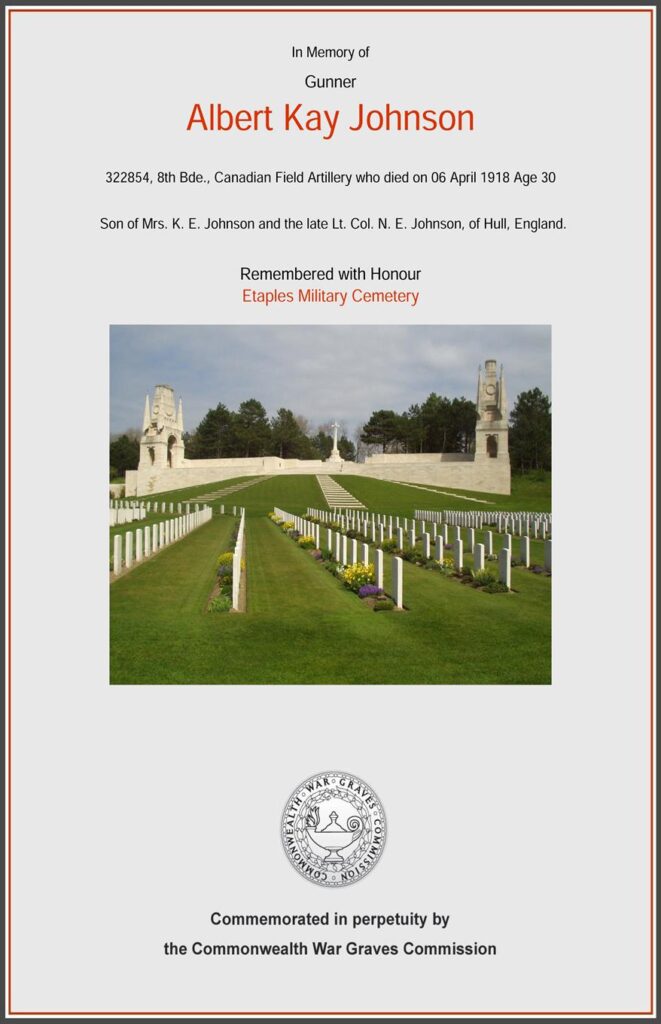

The impressive obelisk monument located close to the Thoresby Street entrance, records members of the Johnson family. These include WW1 CWGC casualties Lt Col VD Richard Ethelbert Johnson and his son, Gunner Albert Kay Johnson of the 8th Canadian Field Artillery.

Lt Col Johnson collapsed and died after attending a function of his RGA Regiment at the Station Hotel Goole on 29 October 1915. He was given a full military funeral at Hull General Cemetery.

His son Albert Kay, had emigrated to Canada around 1913 and joined the Canadian Army at the outbreak of war, but died of wounds in France on 16 April 1918 aged 29. He is buried in Etaples Military Cemetery, but commemorated on the family monument.

8. Cholera Monument

In the late summer of 1849, just two years after the cemetery was opened, Hull was struck by a deadly cholera epidemic, It lasted for three months and took the life of 1860 inhabitants (approx. 2.5% of the population, 700 of whom were buried in this cemetery.

The monument was erected by private and public subscriptions to ‘Commemorate the great visitation’.

The epidemic did have the result of a much improved water supply being provided to the town from the Springhead Pumping Station at nearby Anlaby.

9. Rollitt’s Memorial

Eleanor Rollitt (Bailey) was born in Hull in 1853, the 2nd daughter of ship builder, William Bailey and Mary Badger Ainley. William was a self made man, and a partner in the steamship company, Bailey & Leetham, which was taken over by Thomas Wilson & Co. in 1903.

William was also a JP, and a director of the Hull Dock Company and he lived at White Hall, Winestead.

Eleanor married Albert Kaye Rollitt at the newly opened, St Peter’s Church, Anlaby on 26th August 1872 when she was just 18 years old. Her brother, Walter Samuel Bailey, of The Mansion, Anlaby, married Albert’s sister, Ellen Rollitt.

Albert Kaye Rollitt, was the son of solicitor John Rollitt, and brother of Arthur, also a renowned solicitor who lived at Browsholme, Cottingham. Albert became very successful, eventually became President of the Law Society, and was later knighted.

Philanthropic

Their only daughter, Ellen Kaye was born in 1874, and the family lived at Thwaite House in Cottingham. Eleanor was very involved with local charities, and was a great supporter and benefactor of the Sailor’s Orphanage on Spring Bank. She was also a patron of the training ship T.S. Southampton. This ship trained wayward boys and orphans in the basics of seamanship. It was moored in the Humber at the mouth of the River Hull. Eleanor personally opened bank accounts with the Hull Savings Bank for the boys.

Eleanor was always referred to as charitable and philanthropic. She organized annual visits and fetes at the family house in Thwaite Street, for the children of the orphanage. She also subscribed towards a new wing at the Hull Royal Hospital in Prospect Street.

Lady Mayoress

When her husband became Mayor of Hull in 1883-1885, Eleanor became Lady Mayoress and extended her support for local charities and good causes. She was also very active in the early women’s suffrage movement. Sadly, during her tenure of Lady Mayoress, she suffered heart problems, and died on 11 January 1885, aged only 31.

Her funeral was attended by ex-mayors, councillors and many of the local dignitaries. The cortege, which left from the family house in Cottingham, was lined all the way to Hull General Cemetery, with crowds of in excess of 20,000 people, including the orphans of the Sailor’s Orphan Homes. Her portrait was painted by Ernest Gustave Giradot and hangs in The Guildhall. A marble bust by local sculptor William Day Keyworth junior is also in the Guildhall.

Inspirational Women

10. Timothy Reeves

One of the most impressive tombs in Hull General Cemetery is that of Timothy Reeves and his family.

Timothy Reeves was born in Hull on 2 July 1793 (although the inscription on the tomb incorrectly states 1794), the son of local brewer, Timothy Reeves senior and his wife, Ann Atkinson.

Early life and marriage

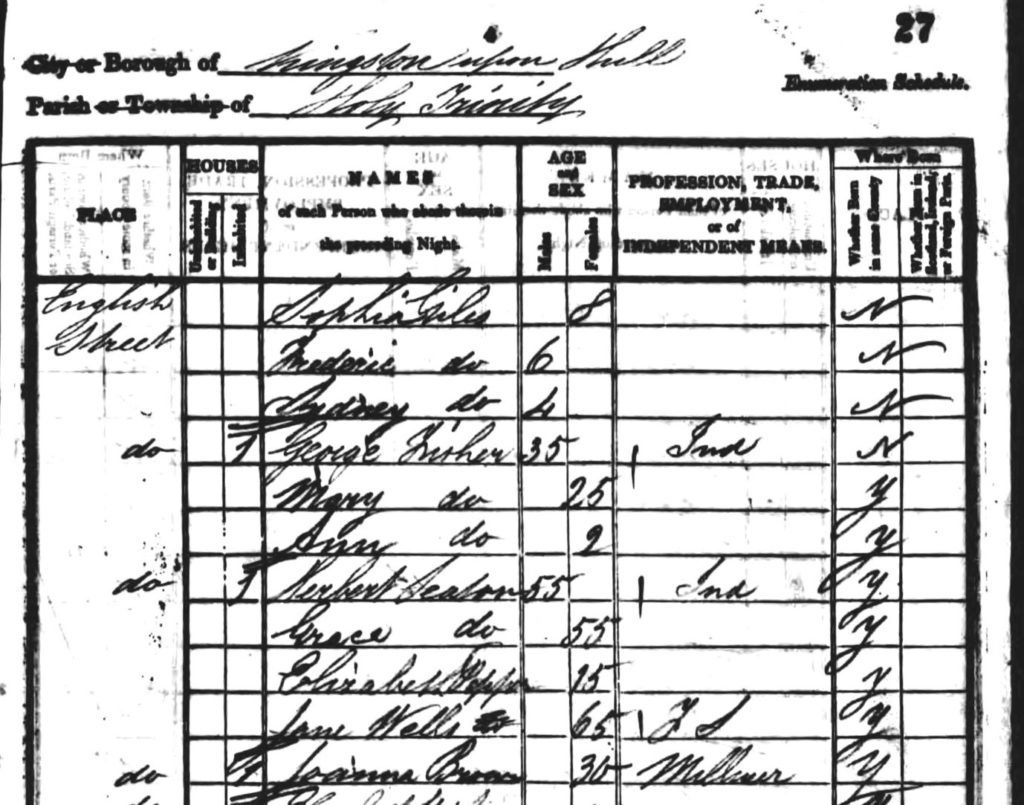

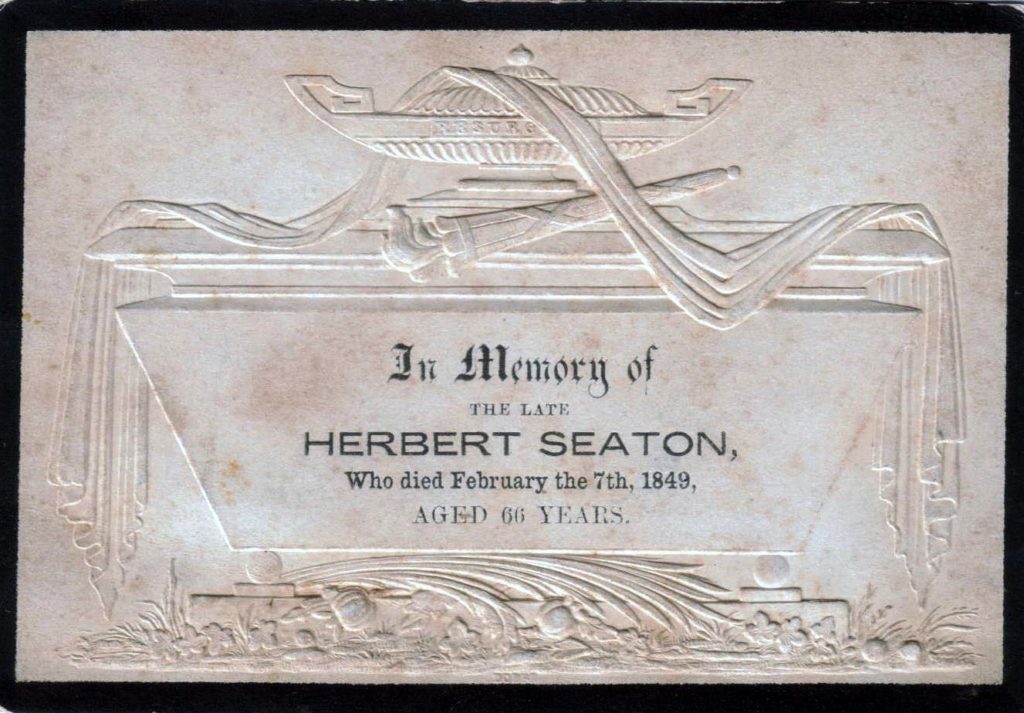

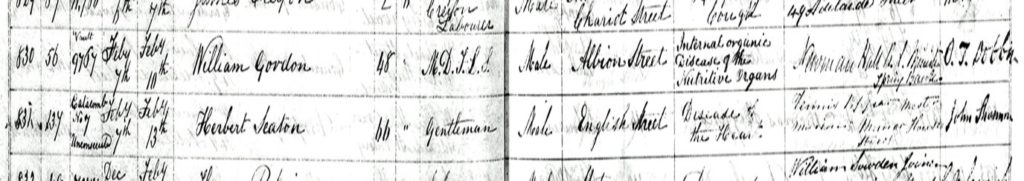

He was articled as an attorney to Robert Galland in 1810 and eventually had his own successful legal practice at 12 Parliament Street. He married Betsey Hill at Holy Trinity Church on 25 August 1823, and initially lived at 32 Neptune Street on the Humber Bank. They had 4 children, including Stafford and Ann Elizabeth. The family later moved to the more prestigious, but nearby address of 31 English Street.

His wife Betsey, died on 7 November 1836 aged 39, and was buried in St James’s Church. Timothy continued to live in English Street, but also lived for a while in Paddington, London. He died of bronchitis and congestion of the lungs at his home on 11 August 1879 aged 85.

Their son, Stafford, who was born on 4 July 1826, went to Trinity College, Cambridge. He spent his early years on the continent, becoming fluent in several languages. Stafford was also studying chemical science and physiology in Bonn. He later became something of an adventurer, and spent much time developing his interests in the Southern States of America. Whilst there he married, Elizabeth Atherton Seidell, the daughter of Charles Ward Seidell in Orange County, Pennsylvania on 30 March 1856.

American Civil War

The couple had two children in America, but with the political changes prior to the outbreak of the American Civil War, he severed his links with the United States. The family returned to England immediately after the birth of their daughter, Ann, in April 1861 just weeks prior to the outbreak of the American Civil War.

At the time of the 1861 census, the family was living in Everton, before moving to Pool Bank Cottage in Welton, (which still exists as Pool Bank Farm, just off a lay-by close to the A63). They eventually had ten children, and are recorded in the 1871 and 1881 census’ as living at Pool Bank Cottage, although his occupation was given as an Annuitant, he was also a journalist for ‘The Times’ newspaper. The family moved to Cheltenham in 1881, where his wife, Elizabeth Ann, died of heart disease on Boxing Day the same year aged 50.

Stafford married Ann Pilmer Withcombe in 1899, and he died at Cheltenham on 26 July 1909 aged 82.

The Ellerman connection

Ann Elizabeth, Stafford’s sister, (Timothy and Ann’s eldest daughter), married a Lutheran ship broker and corn merchant, Johannes Hermann Ellerman, on 5 October 1855 who had emigrated, like many others, to Hull from Hamburg in 1850. They had three children, one of whom, was John Reeves Ellerman.

He was born in the house adjacent to the ‘Hope House’ rescue home for fallen girls, on 15 May 1862. He trained as an accountant, and by acquiring under-priced companies, became a ship owner and investor in many businesses including newspapers and breweries. However, like many multi-millionaires, his personal life was notably modest and private. He was noted as the richest man in England.

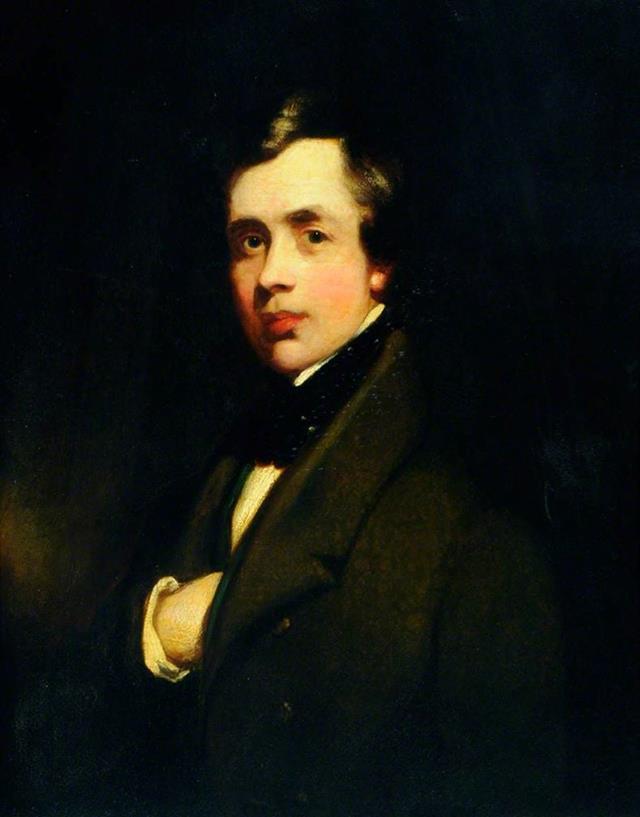

11. Thomas Earle

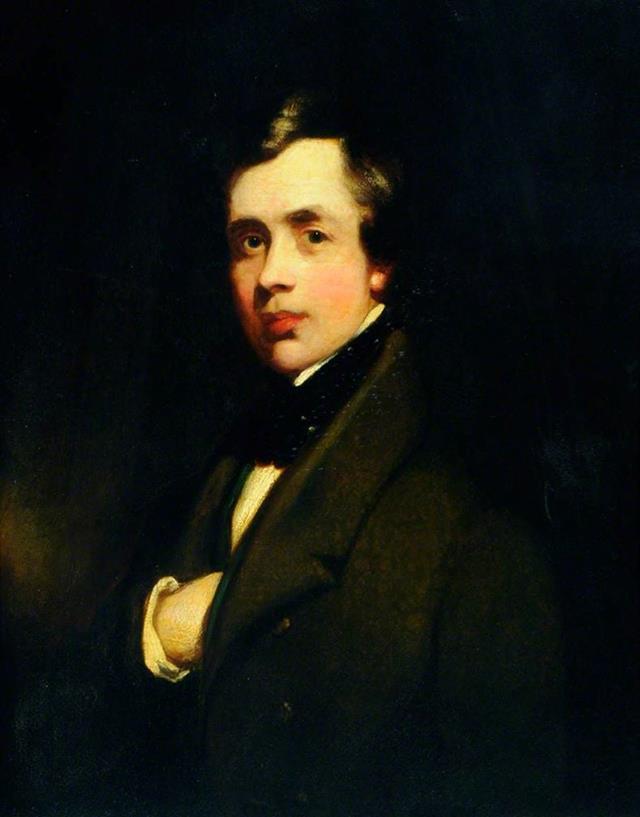

Thomas was born on 9 June1810 at 11 Osborne Street Hull. He was the son of architect, builder and statuary maker John Earle and his wife Mary (Alder). John is recorded in White’s 1828 directory as having premises at 29 Whitefriargate.

Thomas was also the nephew of George & Thomas Earle, founders of Earle’s Cement Ltd, and cousin of Charles & William Earle who founded the Earle’s Shipbuilding Company. His father John designed the Pilot Office on Nelson Street and the Ferres Hospital (now Roland House) on Princes Dock Side.

To London and fame

Thomas was proficient in model making from an early age, and in 1830 he left Hull to work as a modeller and designer for Sir Francis Leggatt Chantrey at his London studio, eventually studying at the Royal Academy. In 1846 Thomas married Mary Appleyard, daughter of renowned Hull builder Frank Appleyard at Holy Trinity Church, Hull. He and his wife returned to 1 Vincent Street, Chelsea where he started his own studio. Thomas and Mary continued to live at the Chelsea address, and were living there at the time of the 1851, 1861 and 1871 census’. They had no children.

He produced several fine statues, monuments and busts, many of them in Hull. These included those of Queen Victoria & Prince Albert in Pearson Park, Dr John Alderson, (now outside HRI on Anlaby Rd), Edward 1 in the Guildhall and several monuments in Holy Trinity, including the magnificent memorial to Thomas Ferres. His own memorial is located in The Minster.

Death

Thomas died suddenly of heart disease in London on 28 April 1876 aged 65. His body was brought back to Hull for burial in Hull General Cemetery where many people attended the ceremony. His wife Mary returned to Hull and lived on Spring Bank, until her death on 12 June 1881 aged 74. They are both buried in a sarcophagus styled, raised tomb that still remains in HGC.

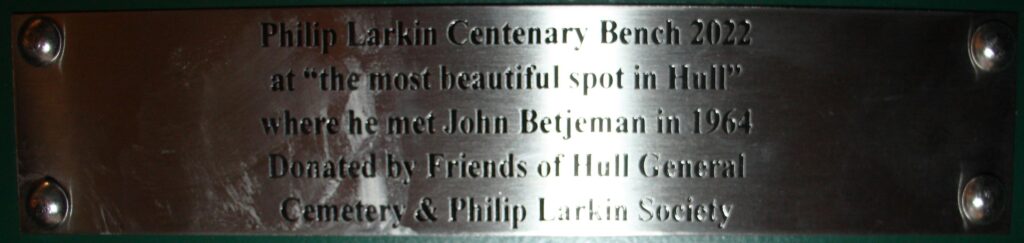

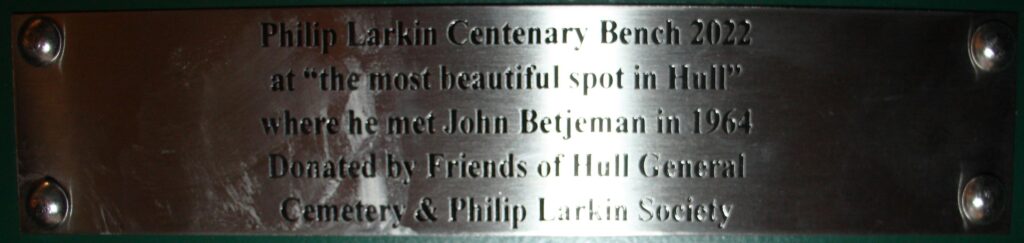

12. Phillip Larkin Bench

In the 1970’s the cemetery was in a state of disrepair and the council were considering removing all of the monuments and headstones and making the area into a recreation park. Some 3,500 headstones and monuments were removed from the cemetery and crushed. Philip Larkin was instrumental in preventing the total demolition and often came into the cemetery, writing a poem about it. Today only about 1000 of the original 5000 headstones remain. Even these few may have been lost with his intervention.

He met with his friend the poet laureate, John Betjaman in the cemetery and a short film was made about the cemetery. In late 2022 a commemorative bench was erected on the spot where the two men were photographed for the BBC. The bench was funded by The Friends of Hull General Cemetery and The Philip Larkin Society.

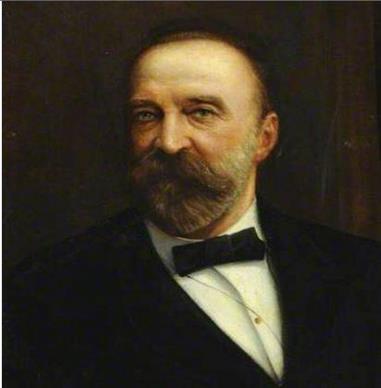

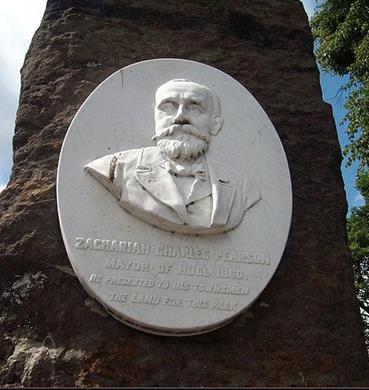

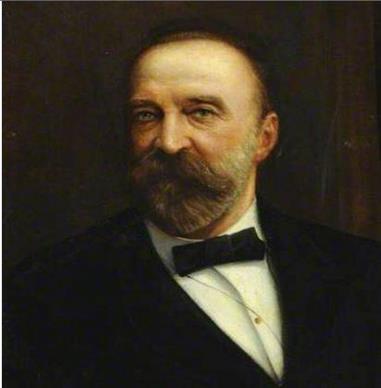

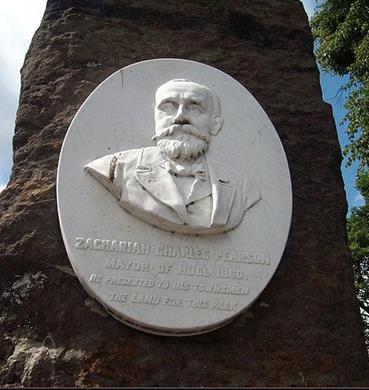

13. Zachariah Pearson

Zachariah Pearson was born in Hull on 28 August 1821. He was one of ten children of Zachariah and his wife Elizabeth (Harker). His mother died on 24 November 1825 whilst giving birth to a daughter, who also died. Zachariah was brought up by his uncle. but he went to sea at an early age By the time he was 21 he was a captain, and owned his own ship by the age of 25.

He married Mary Ann Coleman of Limehouse, London, at Holy Trinity Church on 10 April 1844. They had eight children. They lived at 11 Spring Street, prior to moving to Grosvenor Terrace, Beverley Road. He set up a shipping business with his brother-in-law, James Harker Coleman, with premises in High Street, and trading as Coleman, Pearson & Co.

Success

His partner died in 1851. Zachariah continued successfully on his own, building up a fleet of ships and readily converting from sail to steam. He became Sheriff of Hull in 1858, and was the Mayor in 1859 and 1860. Zachariah never forgot his poor beginnings, and did much to help the poor. This included founding the Port of Hull Sailor’s Orphan Homes in 1860, supporting many charities and building the Beverley Road Wesleyan Chapel. He promoted the building of the West Dock. He also paid for repairs to Holy Trinity Church and supported the installation of the new water supply to Hull.

In 1860 he donated 27 acres on Beverley Road to be used as The People’s Park. He also encouraged the merchants of Hull to stay in the town, by building the large houses around the park.

The American Civil War

However, his fortunes changed with the American Civil War (1861-1865). The two large cotton mills in Hull closed down because of the cotton embargo enforced by the Southern States. This put thousands of people out of work and into poverty.

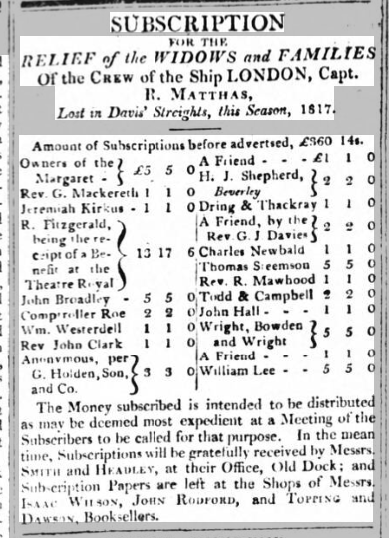

In 1862, in an attempt to re-instate jobs and re-open the cotton mills, Zachariah tried to break the Confederate blockade. This was by taking arms and supplies to the South. However, six of his ships were captured by the Union Navy, and were confiscated along with their cargo, whilst another ran aground. This put Pearson, a staunch Wesleyan, at variance with the abolitionist’s, who believed that that he was supporting the slavery cause.

Bankrupt

He was declared bankrupt in 1864, owing more than £645,000. The People’s Park had to be completed by the Town Corporation. He moved into a smaller house at 64 Pearson Park. Zachariah spent the next 27 years repaying his debts, eventually returning to favour.

He died 29 Oct 1891 aged 70, his wife died the previous year on 12 Feb 1890. They are buried in Hull General Cemetery with his son and other family members. Their grave has a modest headstone, and still exists in the cemetery.

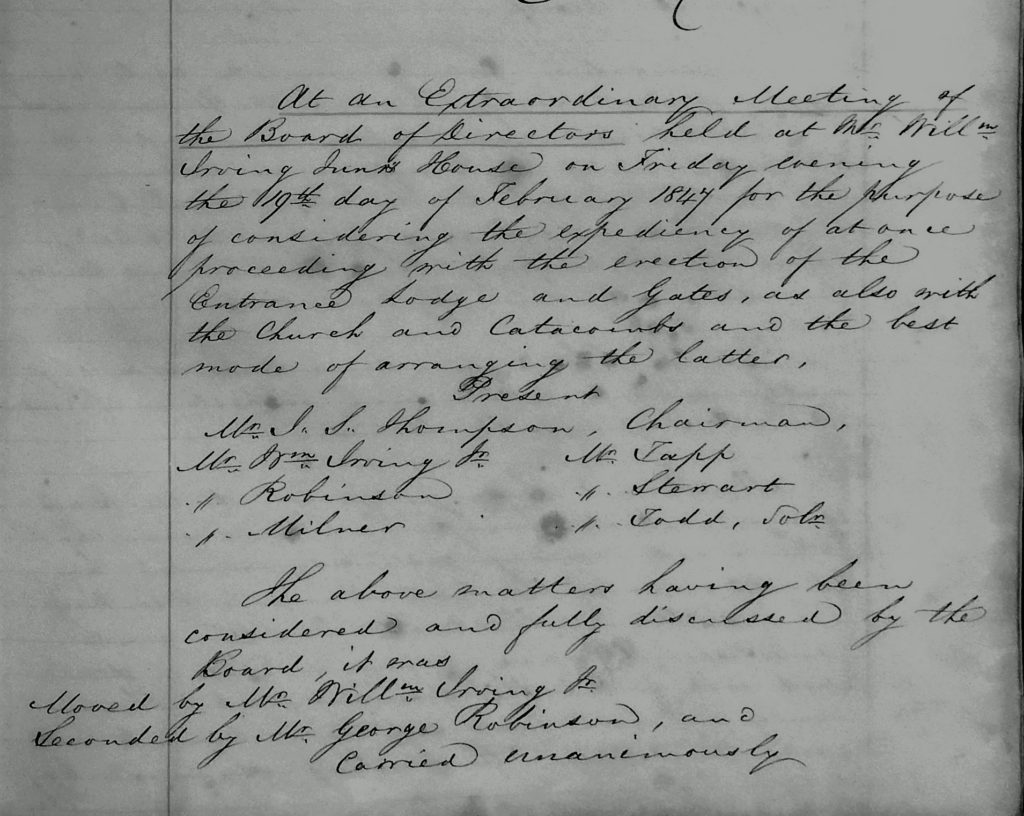

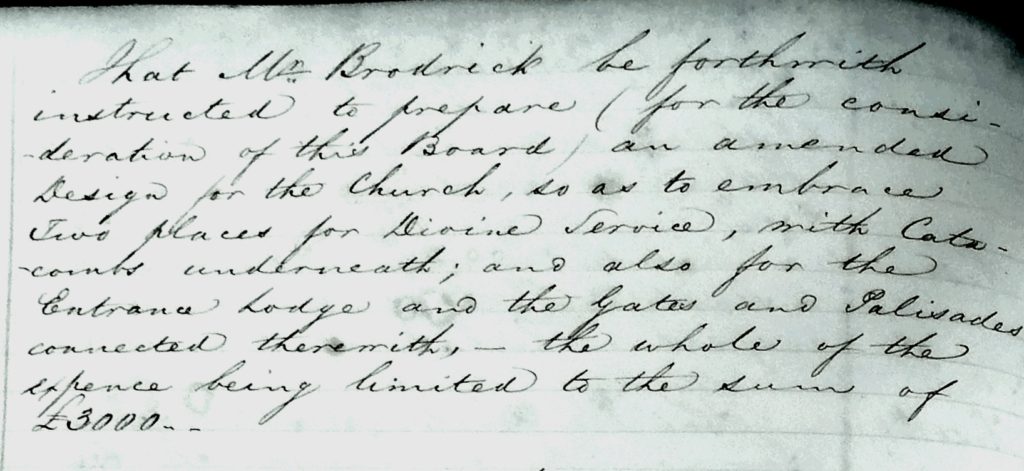

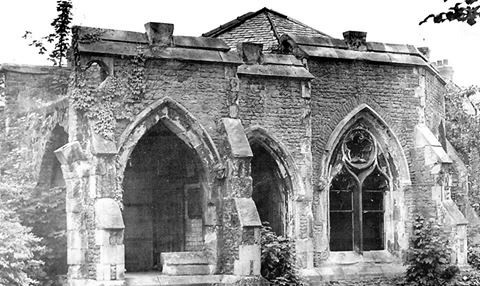

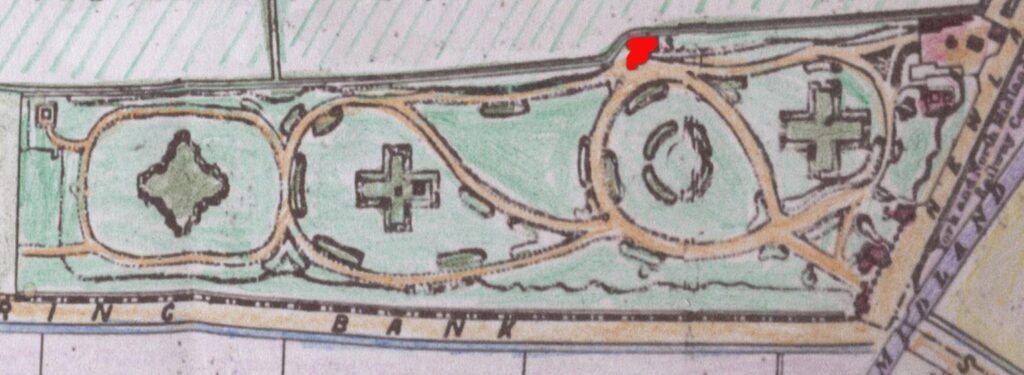

14. Mortuary Chapel (site of)

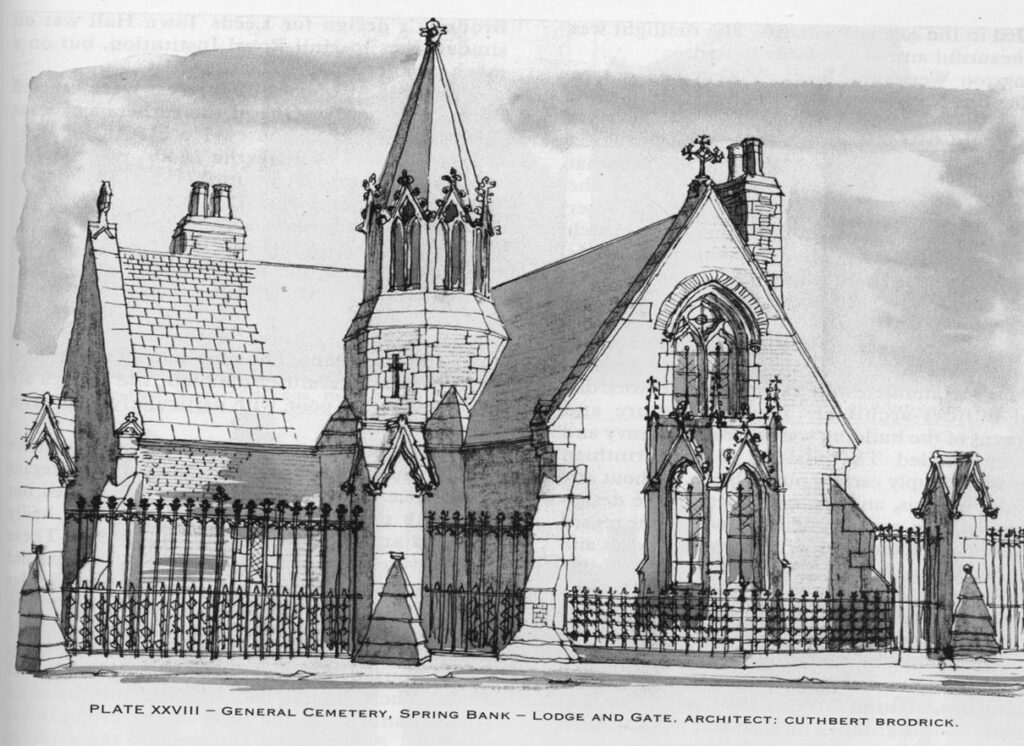

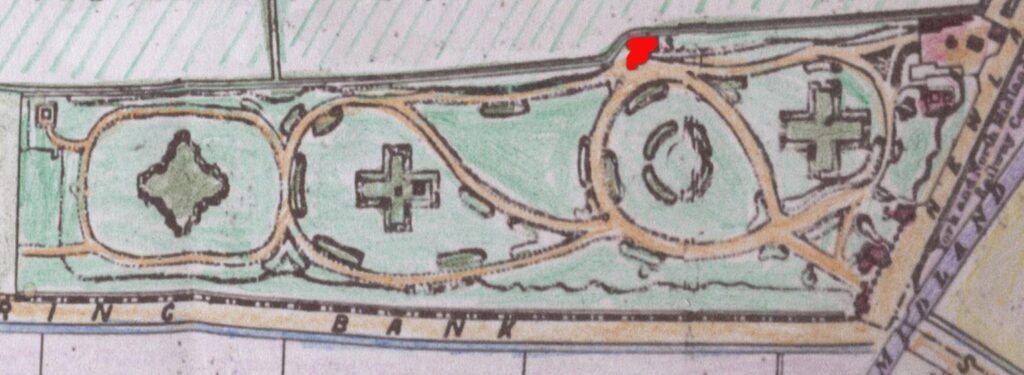

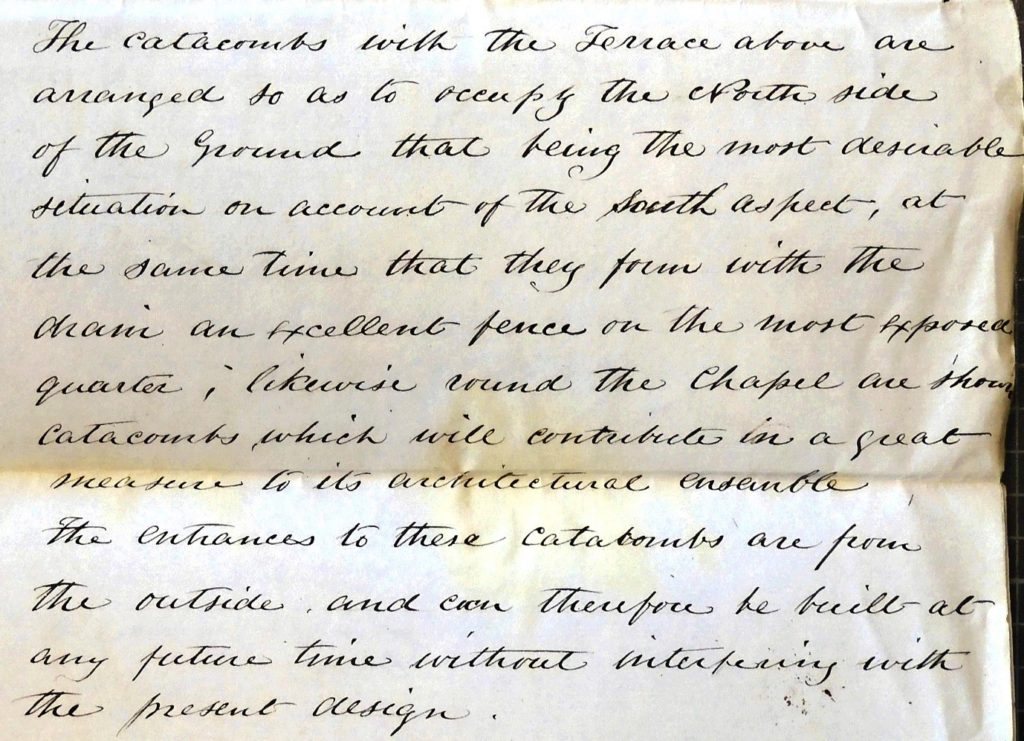

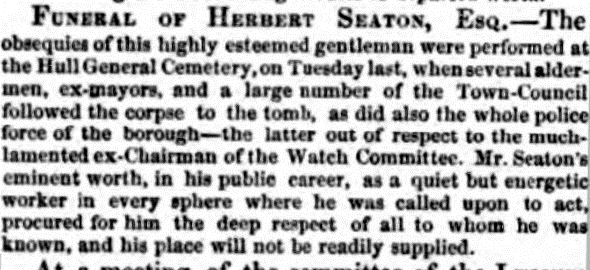

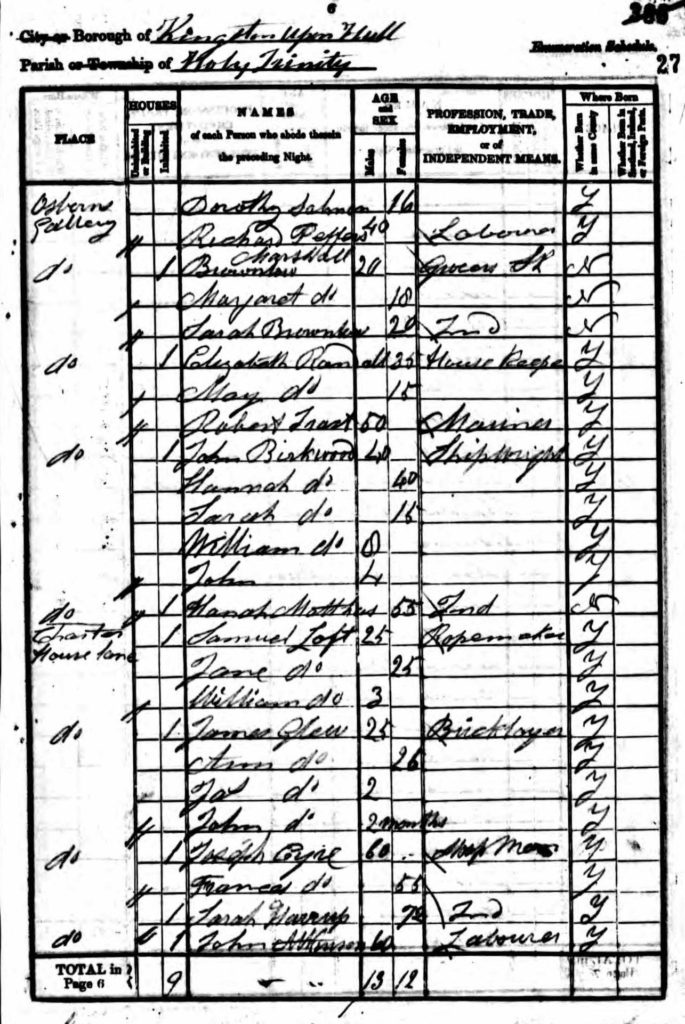

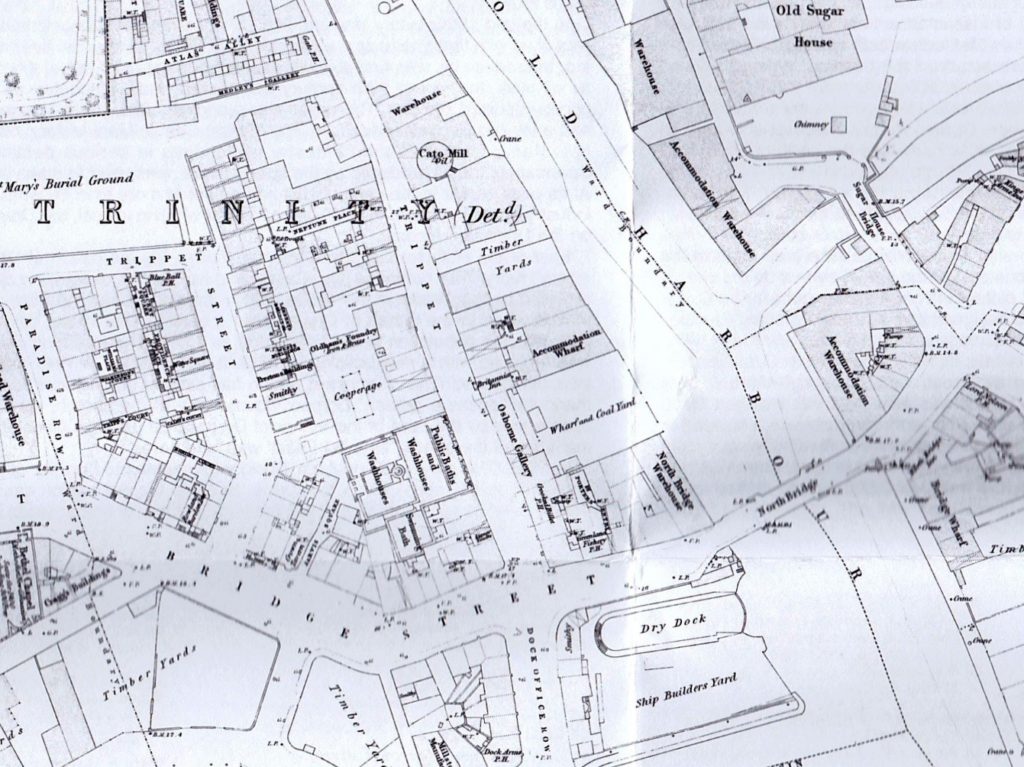

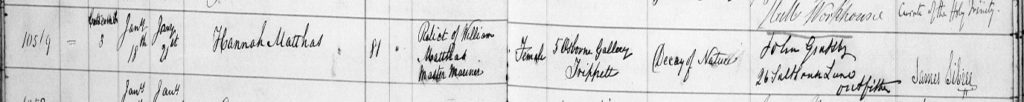

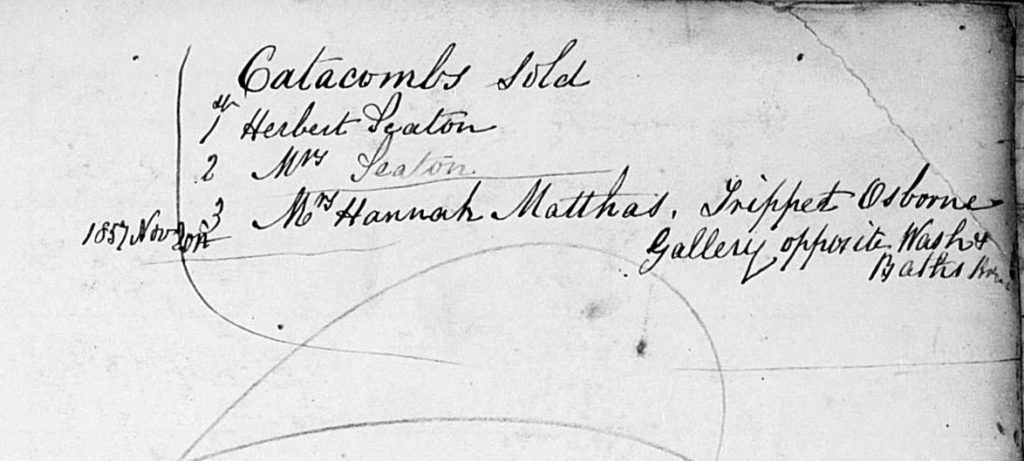

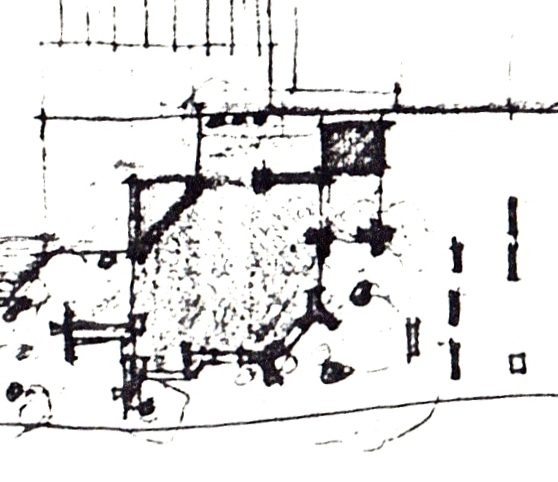

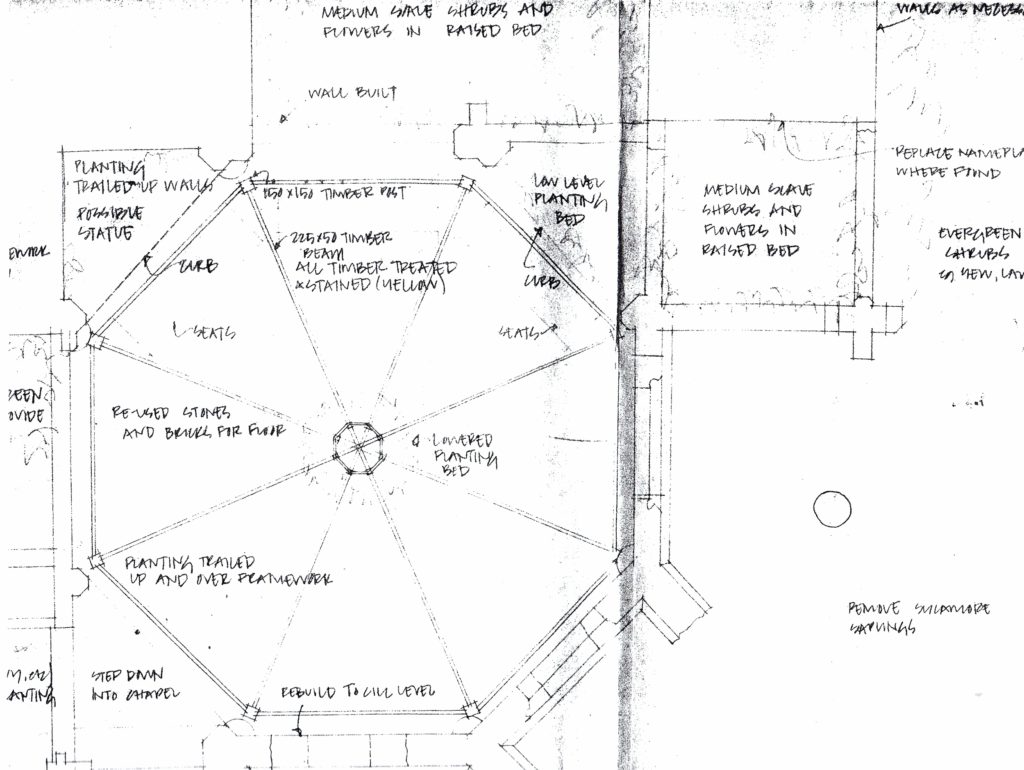

In addition to the Lodge that was located at the cemetery gates on Prince’s Ave, there was a Mortuary Chapel designed by Cuthbert Broderick. It was situated at the rear of the cemetery, backing onto land that was to become Welbeck Street. It also had catacombs nearby, but were seldom used.

The chapel always suffered from damp and unstable foundations, probably due to its proximity to the alignment of an old drain, as seen on the old plan.

Burial services where held here and it was also used as a mortuary. It was finally demolished in 1981.

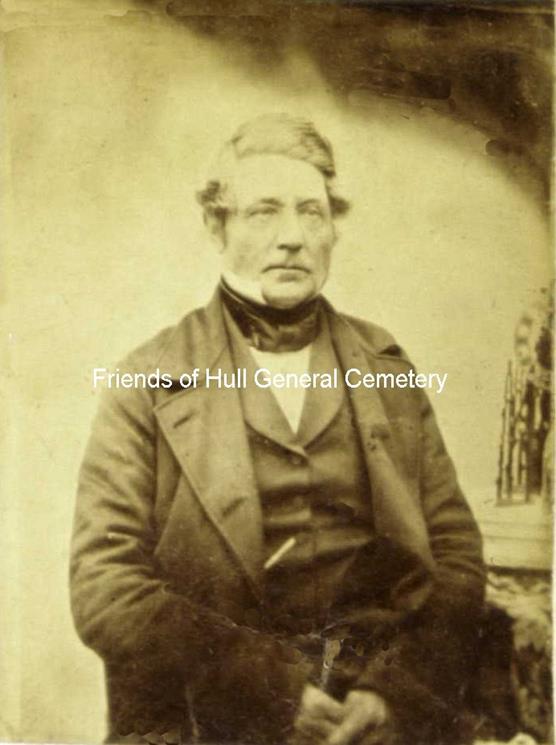

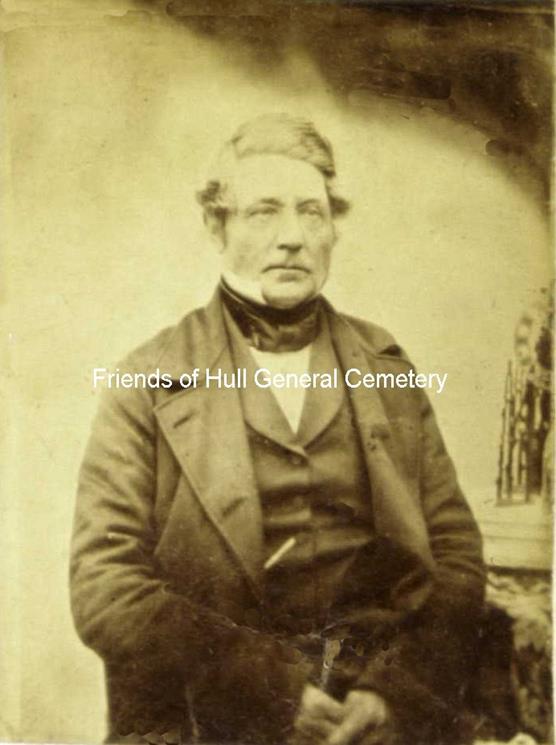

15. James Henwood

James Henwood was born in Sittingbourne, Kent in October 1784. He moved to Cambridge and then to Hull in the early 1800’s. He joined the banking company of Samuel Smiith & Co, formerly Abel Smith & Sons and Wilberforce & Smith initially as a clerk and eventually becoming a partner.

James lived, at what was to become Wilberforce House, in High Street and remained there until his death, being the last occupant of Wilberforce House.

James was a JP, a director of Railway companies and a Deputy Chairman of the Hull Docks Company. He was also involved in many philanthropic and educational enterprises. Always regarded as a benevolent man supporting numerous charities, he was a staunch Methodist all of his life. He regularly attended the Kingston and Humber Street chapels. He was dedicated to his work and many charitable interests and never married.

Death

James died of heart disease on 15 April 1854 aged 70. Many people flocked to attend his funeral in Hull General Cemetery. He was buried in a large stone tomb which still exists.

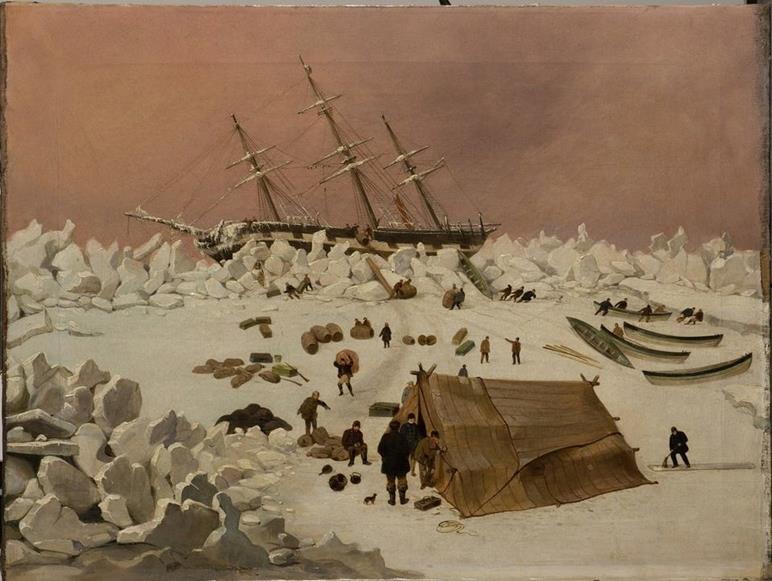

16. Captain John Gravill

John Gravel Graville, was born in Gainsborough, Lincolnshire on 4 March 1802, the son of William Gravil Graville and Ann Solelift. He went to sea at an early age, serving initially as a harpooner on the whaling ships sailing from Hull, later becoming mate on various whalers. These were the Eagle, the Harmony and the William Ward.

He married Ann Solelift at Holy Trinity on 29 Feb 1824, and they had three children, Ann, Emily, and John. In 1851 the family were living at 7 Little Reed Street, off Wright Street, later moving to 6 Mount Place, Hessle Road.

In 1857 Capt Graville was given command of The Diana. This was a barque rigged sailing ship. 117 ft long, with a 29 foot beam, and a depth of 17.5 ft, built at Bremen in 1840. In 1856 the whaler was taken over by Brown Atkinson of Hull, making her first voyage to the Davis Straits in 1856. The following year, The Diana was fitted with a 40 HP steam engine. This was installed by the well-known shipbuilders and engineers Messrs Earle & Co, being the first Hull whaler to be so fitted.

The Whaling Industry

The whalers searched for whale oil and sealskins, resulting in a large fleet of steam and sail whaling ships making the journey to the Arctic in search of the bounty. Leaving their home ports of Hull, Dundee, Aberdeen and Peterhead, at the end of February they called in at Shetland, usually Lerwick. Here they augmented their crews with men who were naturally adept at small boat handling and boat work.

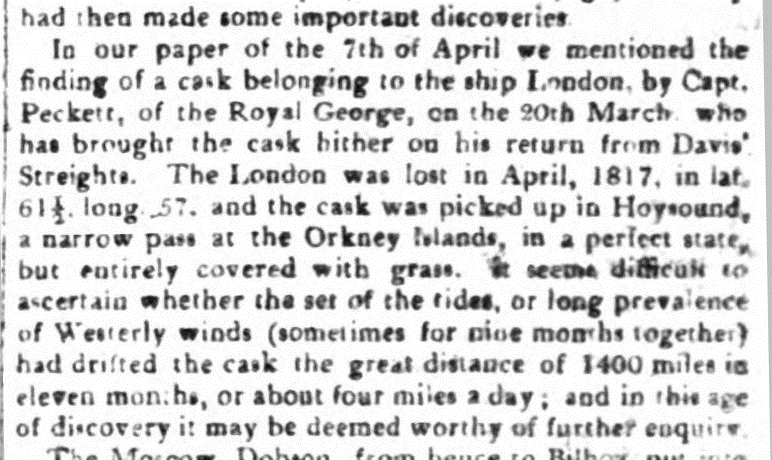

Reports of many whales in the extreme northern limits of the Davis Straits, encouraged whalers to probe even further than what had been accepted as limits of safe navigation. To reach these waters the whalers were forced to run the gauntlet of drifting ice floes and even bigger icebergs driven by gales, and it was inevitable that many whale ships would come to grief, or spend long periods trapped in the ice.

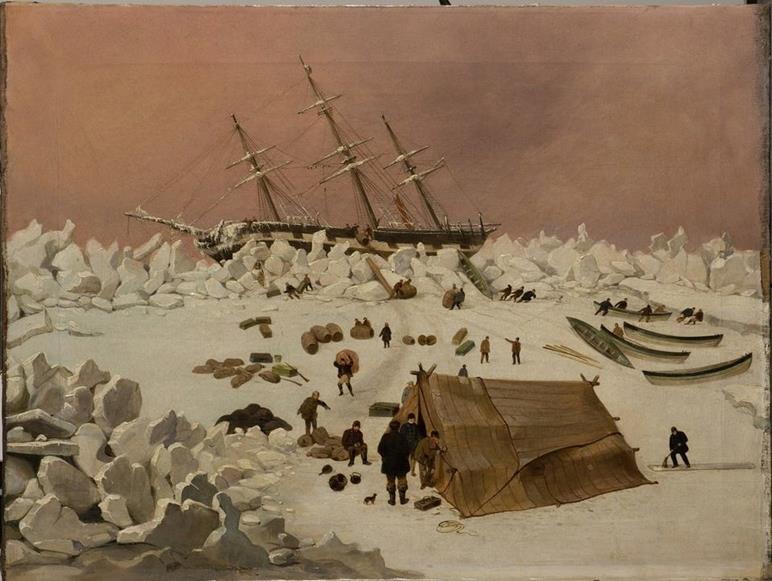

1866

In May 1866, despite a fruitless voyage, the Diana, re-provisioned in Lerwick, and sailed north again in the hope of finding more bountiful waters. Although they caught a small number of whales, the dense ice and whale shortage, convinced Captain Gravill to return home.

However, strong gales and thick ice hampered their journey throughout. Many times Gravill considered abandoning ship. The Diana became damaged by the ice. In December, the crew removed everything that could be moved from the badly damaged ship and laid it out on the ice. Tents were erected, and the crew moved between the ship and the make shift camp whenever ice broke around the ship. In Hull it was feared that the Diana was lost, as it had been gone seven months.

His death and funeral

On Boxing Day 1866 Captain Graville died of ‘dropsy and agitation of the mind, at the age of sixty four. Seven other crewman died on the ice. However, by March 1867 the waters cleared of ice and the crew set sail homeward.

On the 1st April 1867 they sighted the west coast of Shetland, and the next day arrived into Ronas Voe. A further 5 crew members died after arrival. The crew, many of whom were from Lerwick, were all buried there, except Captain Gravill. His body was returned to Hull, and his remains buried in Hull General Cemetery in a ceremony that attracted 15,000 people.

The monument, which still remains, is of Sicilian marble by Keywoth of Saville Street. It was paid for by public subscription.

In 1869, whilst making her way back from the Davis Strait, the Diana encountered a strong gale. She was washed into the Donna Nook sands, on the Lincolnshire coast, and broke up. Diana was the last whaling ship to sail from the port of Hull. Her disastrous voyage ended the whaling industry in Hull.

17. Captain William Cape

The raised tomb was purchased by Master Mariner William Cape for his 3 year old daughter, Barbara who died in 1848, just one year after the cemetery opened.

William was born in Bridlington on 25 September 1809, the son of William and Ann (Clarke). He went to sea at the age of 15. He married Ann Keighley at St Mary’s, Sculcoates on 10 November 1836. They lived at 6 Charles Street and had 6 children. As mentioned above, one of their daughters, Barbara, died of consumption on 11 November 1848, and was one of the earliest burials in the cemetery.

William gained his Masters Certificate in 1850 and became captain of the steamer ‘Emperor’.

The Crimean War

In 1853 the Crimean War commenced when Britain, France and Turkey declared war on Russia. The war was fought mainly on the Crimean Peninsula. Captain Cape and the ‘Emperor’ were seconded to transport troops to Turkey.

The principal naval base in the area and the main port of disembarkation was Varna on the Black Sea. It is recorded that the Captain Cape on board the ‘Emperor’ sailed for the Crimea on 7 April 1854. The ship carried Lord Raglan’s horses for the ill fated Charge of the Light Brigade. It also carried a captain, 2 subalterns, 5 sergeants and 115 other ranks.

Cholera was rife in the area at this time and many soldiers died of the disease. On 4 September 1854 William died aged 44, probably of cholera.

His family after his death

His wife continued living at the Charles Street address, raising their children on her own. William’s mother, Ann, died on 30 January 1855 aged 88. She is buried in the family tomb.

In 1871 his widow Ann Cape is living at 13 Brunswick Terrace on Beverley Road. In the 1881 census she is living at 35 Louis Street with her daughter Catherine and her two widowed daughters, Mary Ann Taylor and Jane Ridsdale.

Ann died on 8 October 1888 aged 81, and is also buried in the tomb, as is her nephew, William Keighley who died aged 52 on 30 July 1856.

The only other readable inscription on the tomb is that of their daughter, Jane Ridsdale. She died of cancer and paralysis on 26 February 1898 aged 58. Jane had married William Henry Ridsdale in 1870.

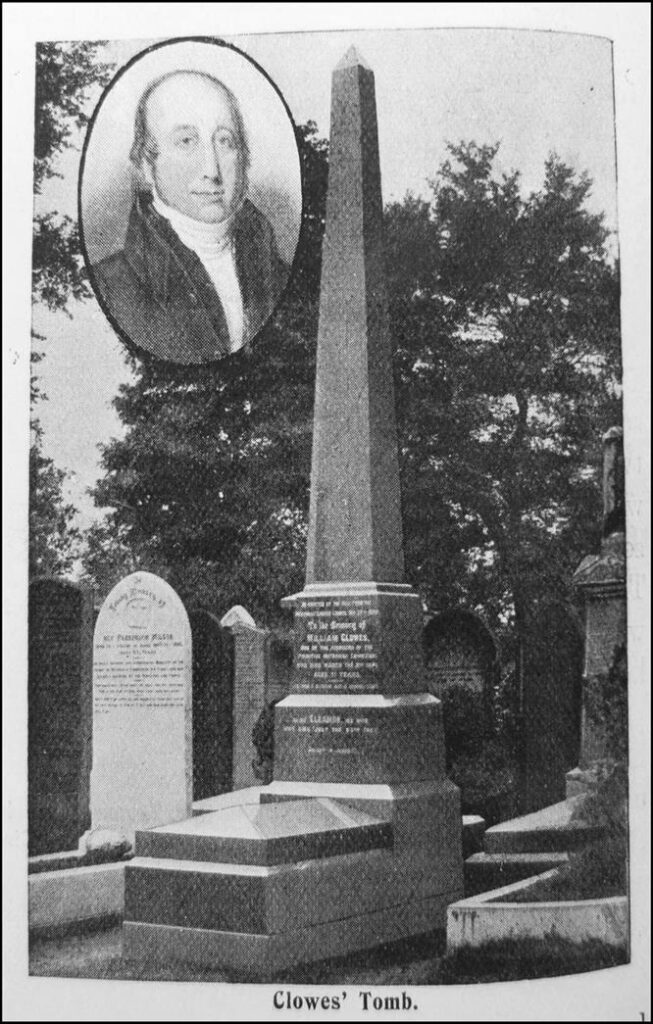

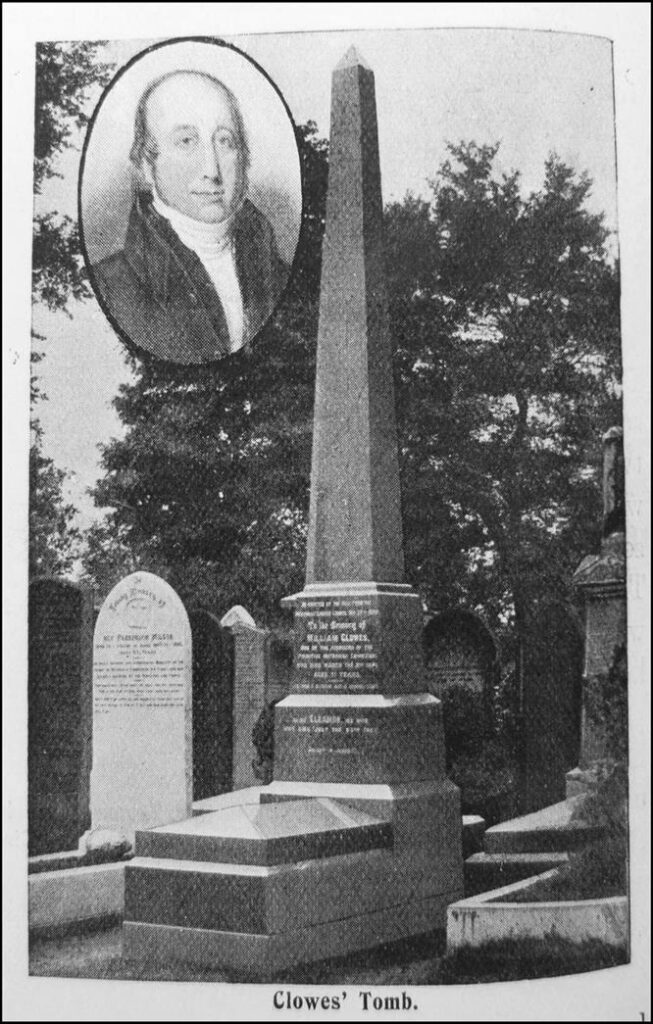

18. Prim Corner (Primitive Methodist Corner)

This section of the cemetery is located close to where the original entrance to the cemetery would have been.

It has several clergy men buried there. These include one of the founders of the Primitive Methodist movement William Clowes. Others are Parkinson Milson, Henry Hodge and his daughter Emma Robson

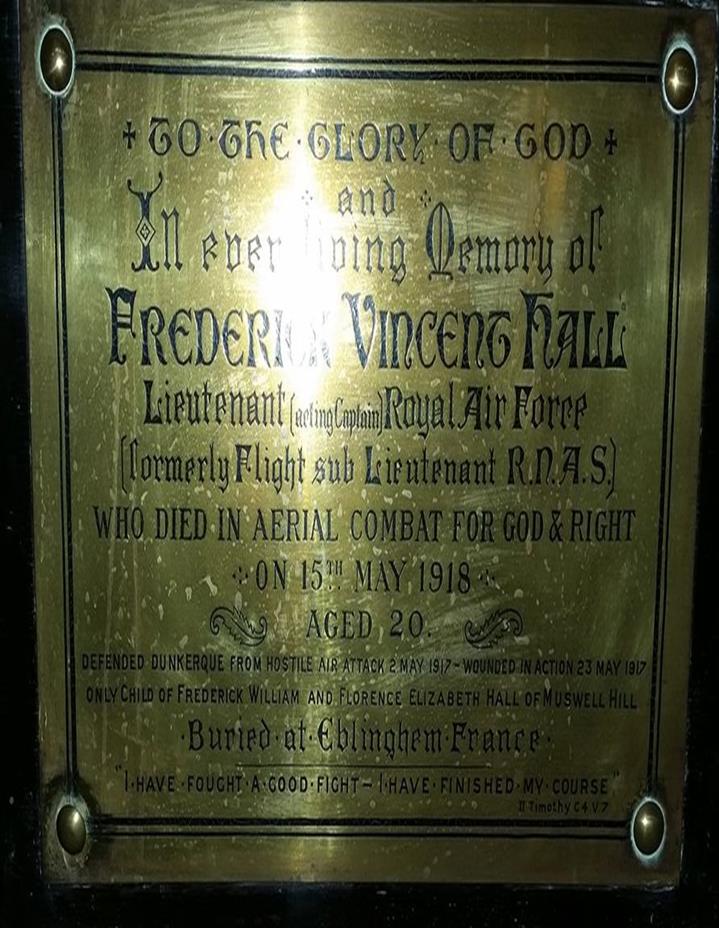

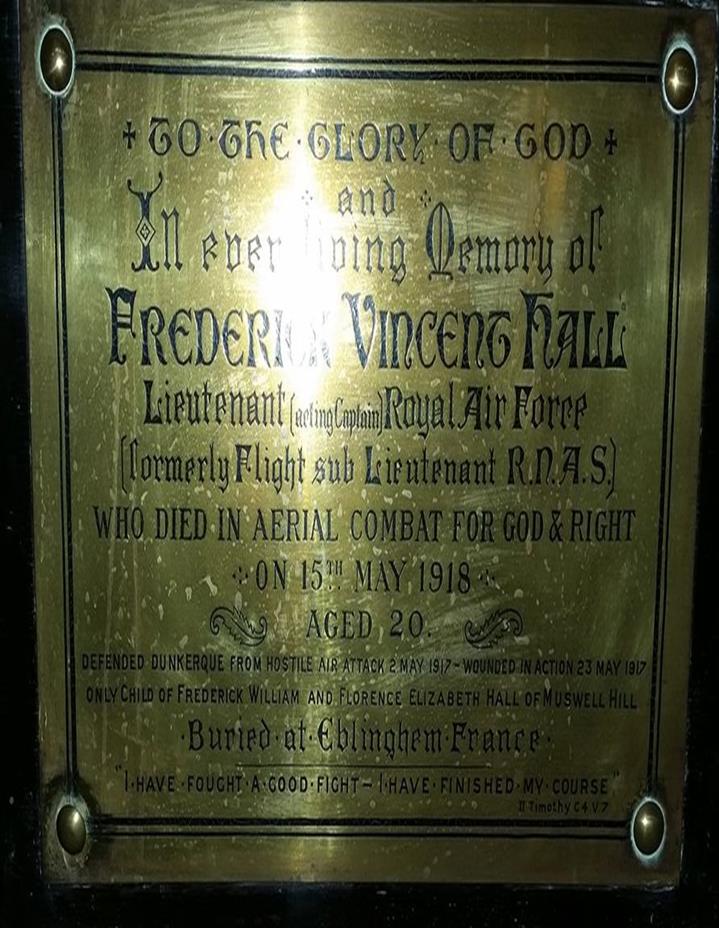

19. Lt. Frederick Hall

Frederick was born in Muswell Hill, London on 20 March 1898. He was the only child of Hull solicitor, Frederick William and Florence Elizabeth Hall (Taylor).

Vincent joined the Royal Navy in WW1. He became a Flt Sub Lieutenant in the newly formed RNAS. This was the forerunner of the RAF. Vincent trained on Sopwith Pups. On 2 May 1917 he took part in the defence of the French village of Dunkirk which was suffering from many attacks by German aircraft.

He engaged a German Albatross plane which he successfully shot down, killing the pilot and the observer. The local press recorded that Frederick and his co-officer, Wing Commander Newbury, went to salute the bodies of the German airmen before their bodies were removed.

In gratitude for their action in protecting the town, the Mayor of Dunkerque awarded the 2 men commemorative medals.

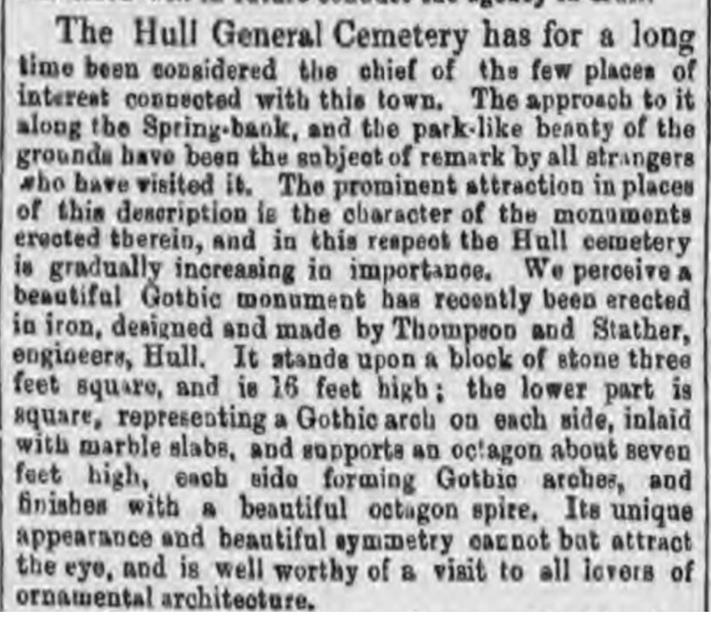

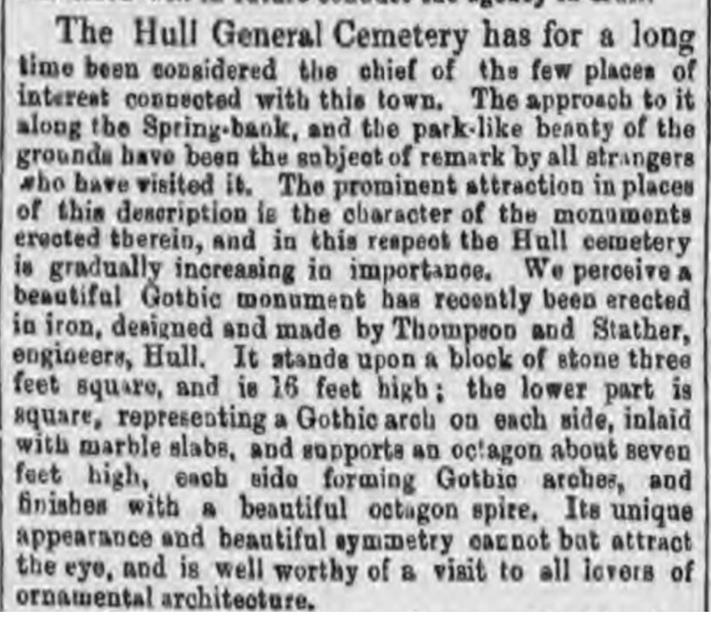

20. Stather Monument

There are three Gothic revival, cast iron monuments in the cemetery, two of which are Grade II listed.

The first one was erected in memory of Thomas Stather’s wife, Elizabeth (nee) Oates. It was manufactured by Thomas’ engineering company, Thompson and Stather. The company had a long relationship with the cemetery. They had been commissioned to manufacture the now Grade II listed gates which still survive to this day.

Thomas and Elizabeth married on 20 February 1836 and lived in Derringham Street. Elizabeth, died of atrophy on the 1st April 1863 aged 58. She is buried in a brick lined vault beneath the monument which is mounted on a sandstone kerb-set.

Thomas married Mary Elizabeth Spower the following year and they lived at Victoria Cottage, Derringham Street.

Thomas died of heart disease on 25 October 1878 aged 66 and is buried in the same grave. Mary Elizabeth died on 4 January 1909 aged 83 and is also buried in the same grave.

The Eleanor Crosses

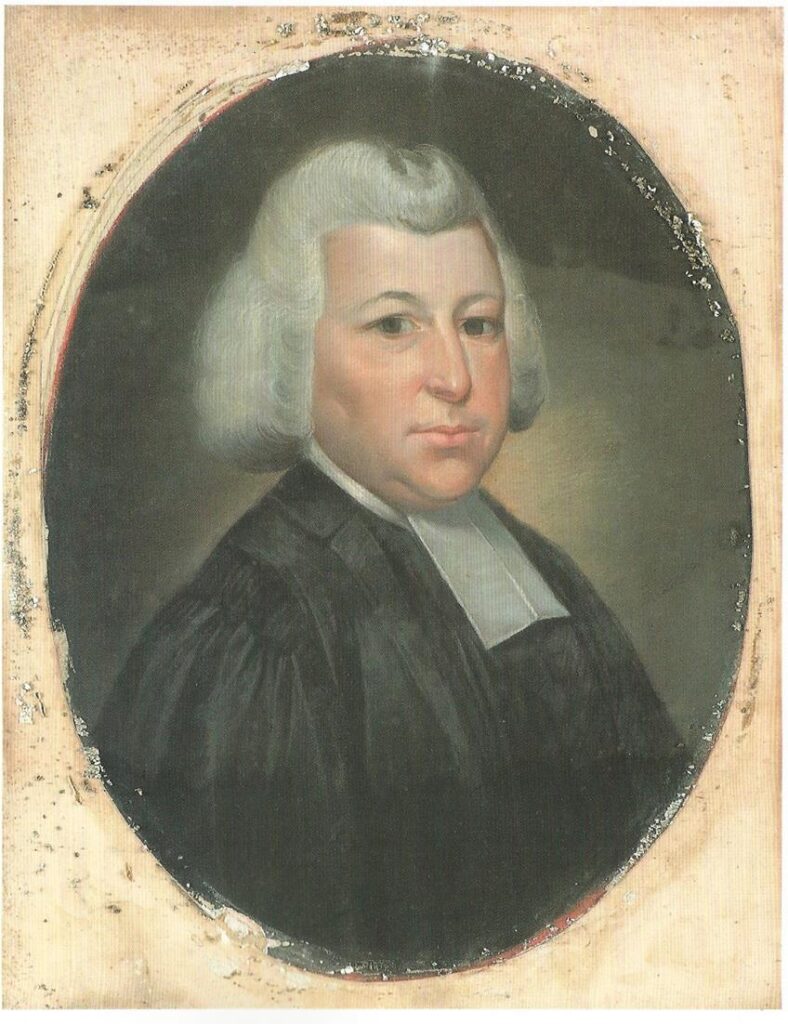

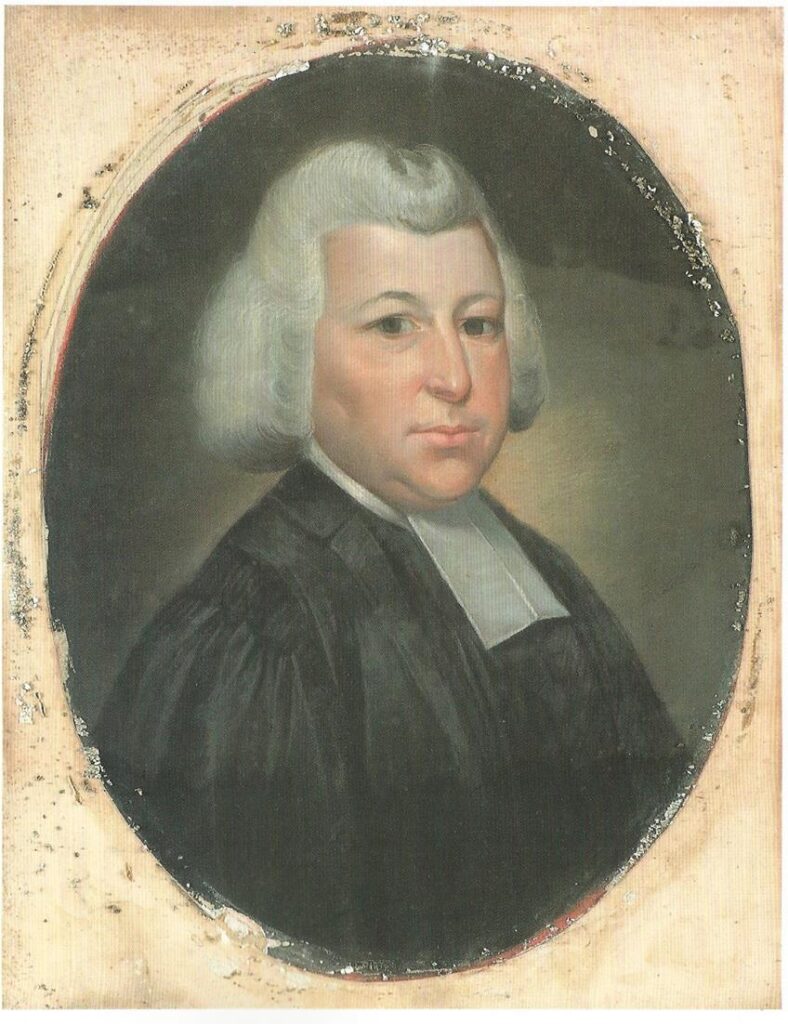

21. Reverend George Lambert

George Lambert was born in Leeds on 12 November 1742, the son of George S Lambert and Susannah Swift. He established himself as a passionate lay preacher and carried out many services in Heckmondwyke and the Leeds area. George married Hannah Ainsley in Leeds on 15 June 1769. They came to Hull the same year where he carried out sermons.

A new chapel

He was a gifted orator. Whilst preaching in Hull he came to the attention of the church leaders who were impressed with his words and impressive bearing. He was invited to take up the position of the pastor of the newly opened Congregational Chapel in Dagger Lane. After much deliberation he accepted the post in October 1769. In 1782 a new chapel was erected in Fish Street. Known as The Fish Street Congregational Chapel it was far more spacious than the Blanket Row church. However, George’s sermons were so popular that the chapel had to be extended in 1802.

George and Hannah had ten children between 1769 and 1786, but in 1831 Hannah died aged 55. George threw himself into his work. He became known as ‘The Pastor of Fish Street’, regularly helping out parishioners and neighbours. George continued as pastor for over 47 years until his death on 17 March 1816 aged 74 years.

He was buried along with his wife at the Fish Street Chapel. The church was closed and the premises acquired by the National Telephone Company, George. As such, his wife and three of their daughters were re-interred into Hull General Cemetery on 17 June 1904.

|