A momentous meeting

On the 25th of October 1977 a meeting took place that would finalise the future look of the Hull General Cemetery site. It was the culmination of a long journey for all the participants. The travellers on this journey were many and all wanted the best for the site. However the view of what that term meant was disputed. This is the story of that dispute.

One of the results of the meeting was the eventual loss of 4,000 of the 5,000 headstones. A significant reduction of the natural environment of the site was also lost. As the title of this piece suggests, ‘a monumental loss’ took place. Of natural habitats and more severely, of irreplaceable historic monuments. So how did that happen?

To find out we need to go back to the swinging Sixties

Liquidation

The Hull General Cemetery Company Directors’ meeting on the 27th August 1968 had a specific item on the agenda, which was not one of the usual ones. The item to be discussed was the cemetery’s future. The directors had authorised their solicitors, Payne & Payne, at a previous meeting, to approach Hull City Council. Their aim was to get the Council to purchase the cemetery from them. This would be the final time for both parties to raise this subject. Put simply, since the late 1850s, the Company had wanted to off load the Cemetery to the municipal authorities. In the past, each time this was discussed, both parties found some objection to finalising the deal. Therefore the Company directors were not hopeful this time either.

At this same meeting though, the directors faced the future square in the face and realised that the Company’s time was at its end. So the first steps towards the liquidation of the Company began.

Deja Vu?

However, this wasn’t the first time the liquidation of the Company had been broached at this level. The Directors’ meeting of the 8th September 1965 had an agenda item entitled, ‘Disposal of the Cemetery’.

But by 1968 the company had hit the wall. Its finances were non-existent. Its main income stream was the rental on the two flats on Spring Bank West that it owned, rather than its primary function of selling burials. The Company could afford no staff other than a part-time secretary, who also undertook the cemetery supervisory duties, although those were sparse now. It also employed an 86-year-old man to perform odd jobs on the ‘as and when’ basis. The Company could no longer maintain the grounds. It could not upkeep its boundary fencing. The maintenance of the graves it was paid to maintain stopped. Its stone masonry business had been wound down long ago. It rented out the old stone yard to a builder to park his lorry. It was defunct as a viable business and it knew it.

This approach to the Council could be seen to be the Last Chance Saloon for the Company. Could it afford to buy a round?

Turned down once again

Sadly, the response from Hull City Council was as expected. The Council were not against taking over the cemetery. To do so would probably save the Council money in the long run. It knew it was only a matter of time before the site fell into their hands.

The problem however was the finances. The Council could not justify taking on the liabilities of the cemetery company, even for nothing, if the shareholders did not contribute to the costs of reclaiming it from its present poor state. As they said, they had a responsibility to the rate-payers, and they felt the first port of call for money to refurbish the cemetery should be on the shareholders.

This was known as a Return of Capital and it proved a stumbling block, and it had been, whenever the idea arose of the Council taking over the site. As most of the shareholders were dead or now lived away from Hull, the Company could not see how the Return of Capital could be accomplished. And so, the idea of the Council taking over the cemetery fell at the same fence yet again.

The Limited Company gambit

The Company though were determined that this time they would seek a solution. It may not be the Council who took over the cemetery, but the directors were sure that the responsibility for it was no longer going to be theirs. They, therefore, turned towards the liquidation route. But to do this the Company needed to change its structure.

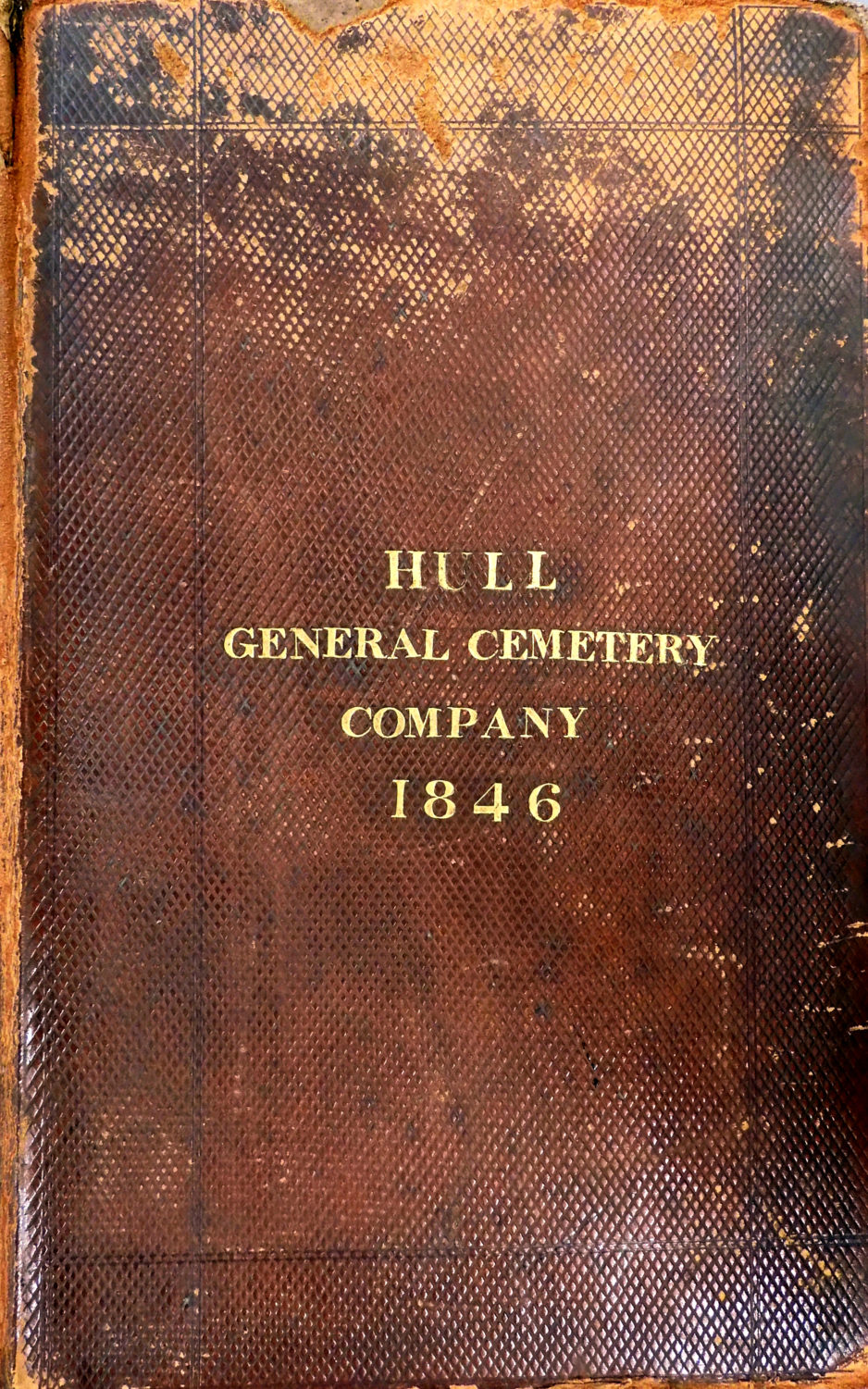

In 1845 the Cemetery Company was set up as a joint stock company and in 1854 it became an incorporated company by Act of Parliament. Neither of these structures allowed the Company to dissolve itself. As such, a change to the Company’s structure had to be made.

To achieve this end, the directors organised an extraordinary general meeting of the shareholders. The scale of attendance at this meeting showed how far the cemetery’s fortunes had fallen. In the Cemetery Company’s early days the AGMs used to be accommodated at the Vittoria Hotel on Queen Street and were usually attended by a couple of hundred people.

First steps to the edge

This meeting on the 19th August 1970, at the offices of A.J.Downs, Solicitors at 77A, Beverley Road, was significantly different in scale

A.J.Downs had been a previous chairman of the Company, and although he was now dead, his company still had a residual interest in the Company’s fortunes. The other factor at play here was that the Cemetery Company would not have to pay for the room for the meeting. Yes, the Company were in such straits that such small points as this were vital.

The meeting was attended by 10 shareholders representing only 153 shares. Seemingly minimal, this was probably the majority of the shares in circulation at this time. Many of the Company’s shares had been surrendered by their owners over the years to the Company, in exchange for grave spaces. Over time the number of shareholders had decreased bit by bit and the result was plainly evident at this meeting.

Decision time

The decision reached at this meeting was that the directors of the Company should pursue the aim of becoming a limited company. This goal was achieved by early 1972, and the Company directors now proceeded to take steps to dissolve the Company.

At a further Extraordinary General Meeting of the shareholders on the 22nd May 1972, a resolution was put to the meeting by the chair. This stated baldly, ‘that the Hull General Company be desolved.’ (sic)

At the last ever board meeting of the Company, held on the 6th June 1972, the chair told his fellow directors that the liquidation would commence when the liquidator was presented with the petition to liquidate the Company. He said he believed that would be in July and be completed by the October of that year.

The chair was a little optimistic about the timing. The final disclamation of the liquidation process was completed in October 1973.

Now we come to the involvement of Hull City Council in the future of the Hull General Cemetery site. Ultimately this involvement led to the October meeting in 1977.

The Council steps in

On the 19th June 1974, Hull City Council completed the purchase of the cemetery for the princely sum of £5. As we’ve seen already, it’s extremely doubtful whether the Council wanted it. However if they didn’t buy it, who else would?

Surprisingly, one interested group made a bid for it at the last ever board meeting of the Company back in 1972. That, however, may be another story for later.

Although the Council had bought the site, as the Hull Daily Mail said, the Council faced an estimated bill of around £60,000 to bring the cemetery into a fit state. That ‘fit state’ for the cemetery was based upon making the site into a ‘leisure resource’. The Town Clerk, A. B. Wood, said the cemetery was ‘a public disgrace’, a statement which obviously heralded some fundamental changes. Those changes would soon be evident.

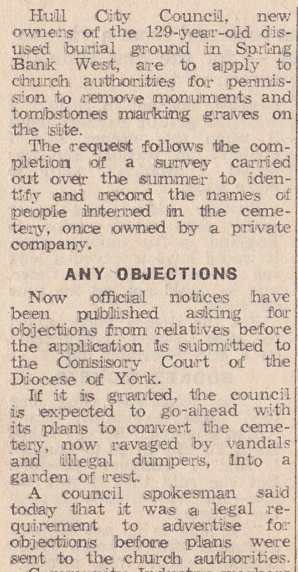

However, some hurdles had to be overcome first. The Council had to apply to the Consistory Court, an ecclesiastical body, for what was called a ‘Faculty’. This would allow the Council to develop land that has had burials on it, without recourse to planning permission.

There’s going to be some changes

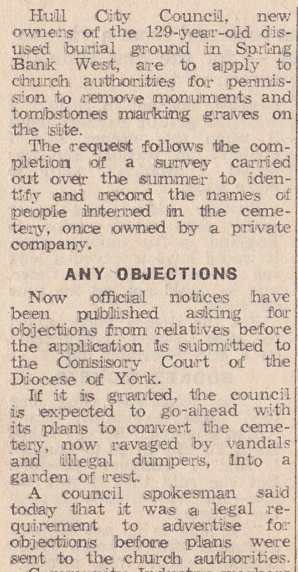

On 28th October 1975 the people of Hull were told by the Hull Daily Mail what the Council were planning.

Under the headline, ‘Bid to clear Hull Cemetery’, the intimation that the term ‘clear’ involved large scale demolition of headstones was revealed by the newspaper item above.

The Friends’ site

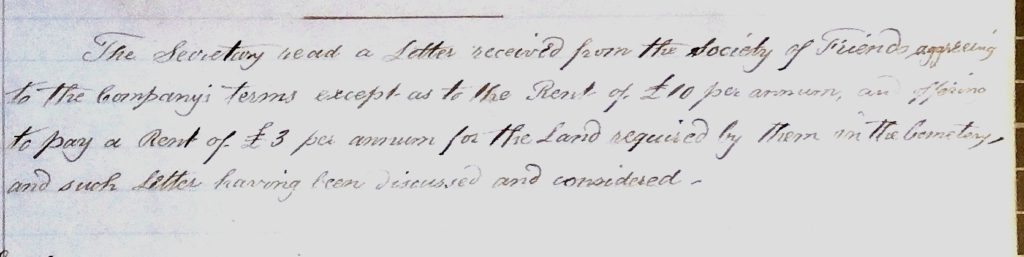

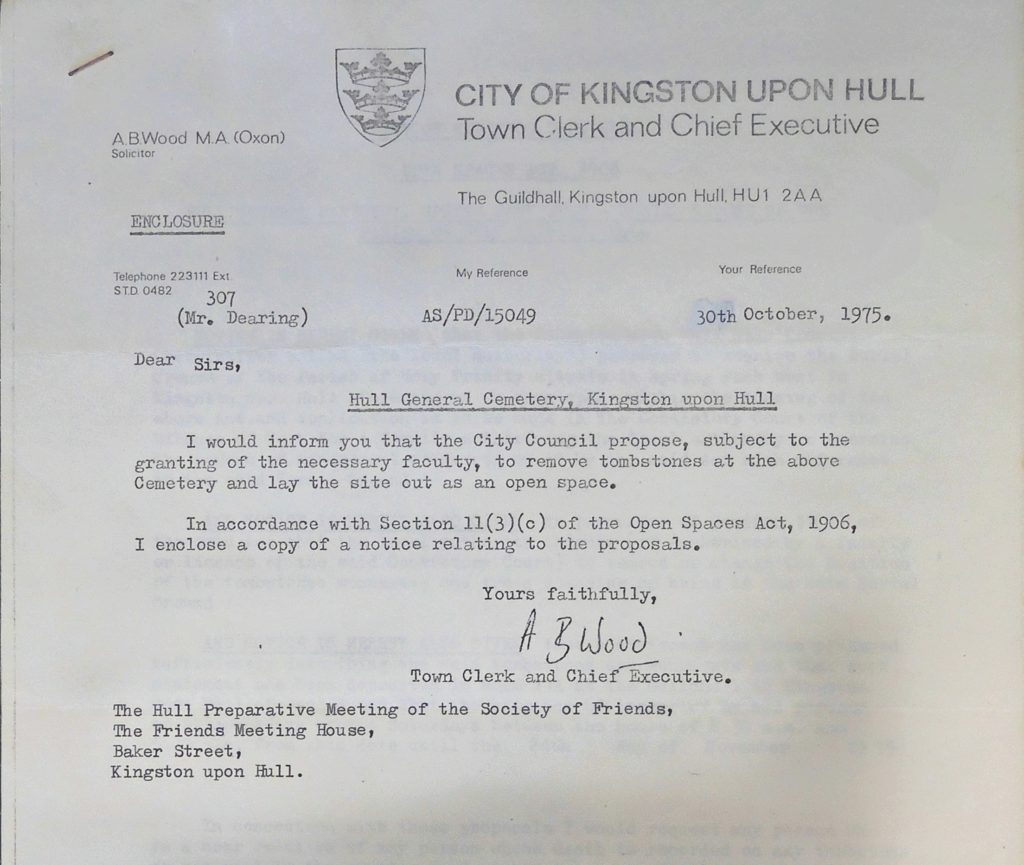

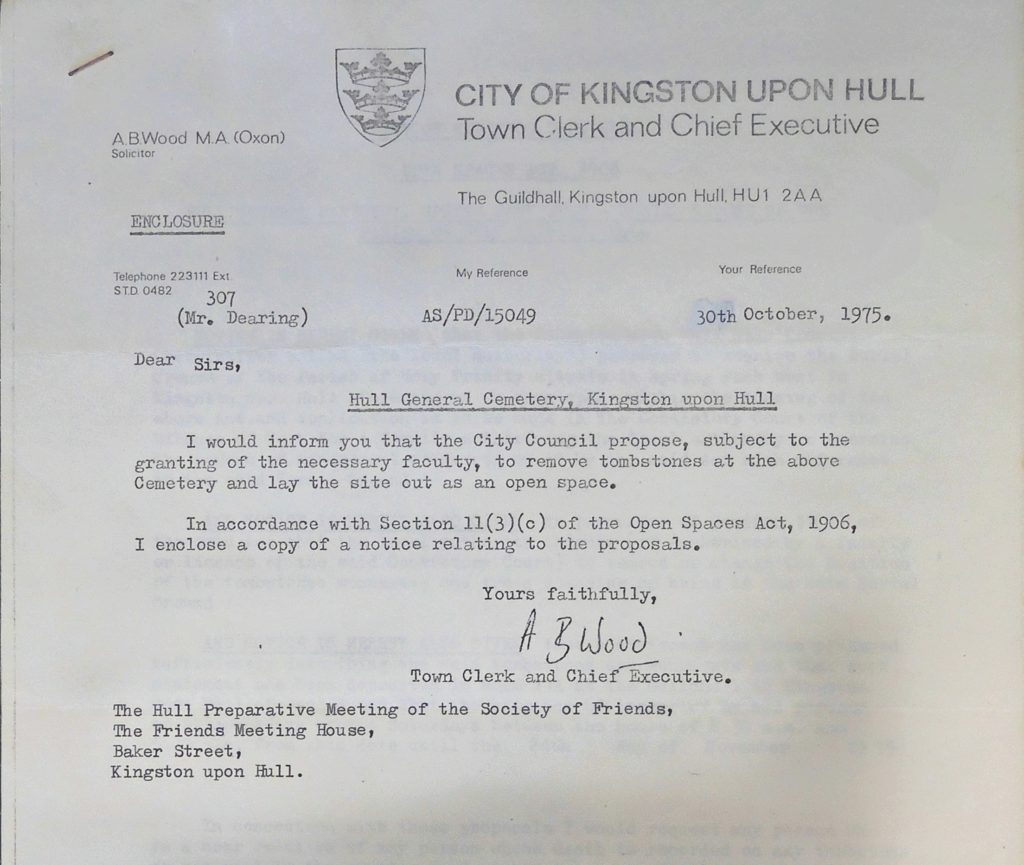

Two days later, the Town Clerk wrote to the Society of Friends regarding these plans. What the City Council appeared to have forgotten was that the Friends had a 999 year lease on their part of the Cemetery. Any plans relating to ‘clearance’ with this part of the Cemetery needed careful handling.

Later, during this process, the Council recognised that the Friends burial area was outside their remit. With the promise from the Friends that they would maintain their burial site, the Council shut its eyes and moved on. It had another 12 acres to ‘develop’.

Repeating the past

As the newspaper item above stated, the Council was to publish official notices of their plans for the site. This would enable people to raise objections to these plans.

To some extent this was a tried and trusted method that the Council had used before, during its programme of the levelling of the ground in all the municipal cemeteries. This programme began in the 1950’s and continued until at least 1974. This programme also included the development of other burial grounds outside their original control, that had fallen on hard times. These were Division Road cemetery, the Drypool and Southcoates burial ground, St Peter’s churchyard, Drypool and St Mary’s burial ground in Trippet Street.

Customarily from ancient times, graves were often ‘banked’ and ‘sodded’ and, of course, a large number of them had kerb sets erected on the grave plot. Thus a cemetery of the period often looked like a long series of hummocks interspersed with kerb sets.

The problem of grass

Maintenance was obviously a problem on a site like this. Grass cutting machines were nigh on impossible to manoeuvre over such ground. From the late 1950’s, the Council instituted the ‘lawn’ area development in both the Northern and Eastern Cemeteries. These were the only cemeteries still undertaking large scale amounts of burials at that time. This ‘lawn development’ was to be the pattern for new burials in those cemeteries and still continues in this way today. These areas could and are maintained by grass cutting machines.

This left the problem of what to do with the vast majority of the areas of all the municipal cemeteries that could not be ‘lawned’. Maintenance of the ‘banked’ graves was undertaken by scythe. It was, as I know from experience, an arduous task. One often felt that the grass was growing quicker than you could ever scythe it. Just using a scythe, sharpening it, keeping it sharp after blunting it on stones and clods of earth, and all on a hot day was a trial. And of course by the time you had finished the plot you were on, the grass you had first cut was already in need of a trim. We members of the workforce all thought it was the equivalent of the painting of the Forth Bridge but probably much less fun.

A cunning plan

The Council came up with a solution to part of the problem. They decided to level the ‘banked’ graves so they could be machine cut. The ‘sodding’ of graves was to be abandoned. However, the kerb sets would still present a problem to a straight run for the grass cutting machine. To solve this problem the Council came up with a plan. It would write to all the owners of graves that had kerb sets, large monuments or headstones on them. These monuments would hinder the proposed efficient cutting of the grass.

The Council offered to the owners a replacement headstone plus it also offered to meet the cost of erection of said headstone, if the owners allowed the Council to remove the kerb sets. It also offered to remove the kerb set and still leave the headstone that had been attached to the kerb set in situ, burying the bottom part in the ground. Just think of that. All of those old headstones you see in Northern, Western, Hedon Road and Eastern were once upon a time just the head of kerb set.

The Council also, rather cunningly, said in the letter, that not responding to the letter meant that the grave owner was accepting the offer.

Address not found

Now, when the grave was originally bought, the address of the purchaser was taken for the record. Over the intervening period, some of those addresses may have disappeared. This may have been due to Council clearances of unfit habitations, or possibly the result of aerial bombardment in World War 2. No matter, the Council still wrote to that address because, and to be fair, it was the only address they had for the grave owners.

However, it was also done in the almost certain knowledge that they would not receive as many replies and so could go ahead and remove the kerb sets.

Thus we have the cemeteries that we now know. And, as this system had worked so well for the Council in their own cemeteries, they now proposed to use it in Hull General Cemetery.

However, in this case they did not write to every relative. They simply posted a notice up in the cemetery for three months.

Objection overruled

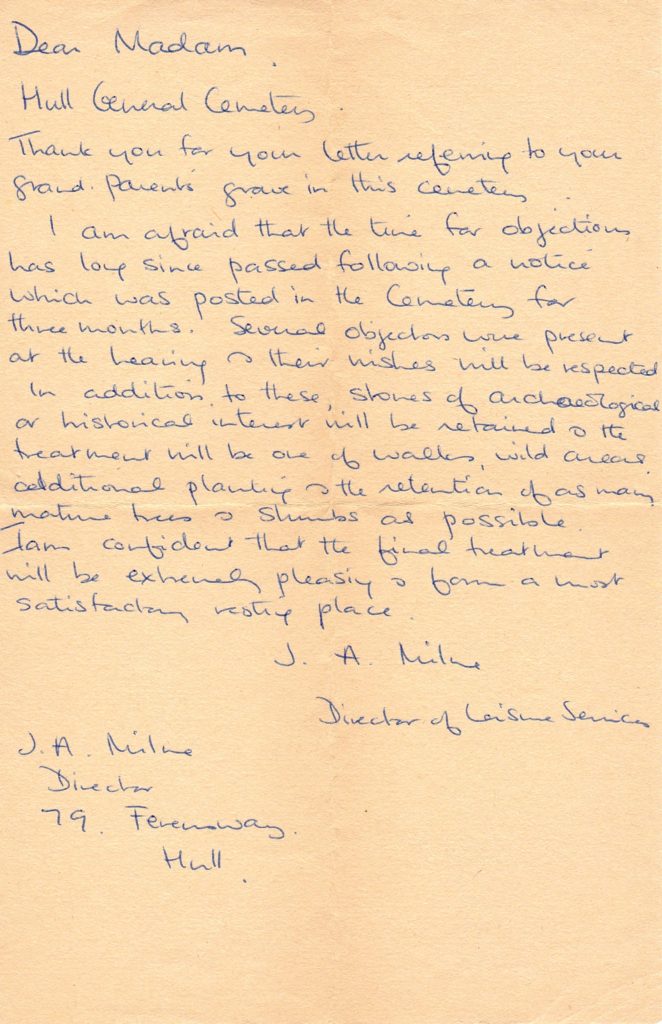

Surprisingly, they did receive a number of objections. At the Consistory Court hearing in the second week of October 1976, there were 33 objectors, most of whom were relatives of people who were buried in the Cemetery.

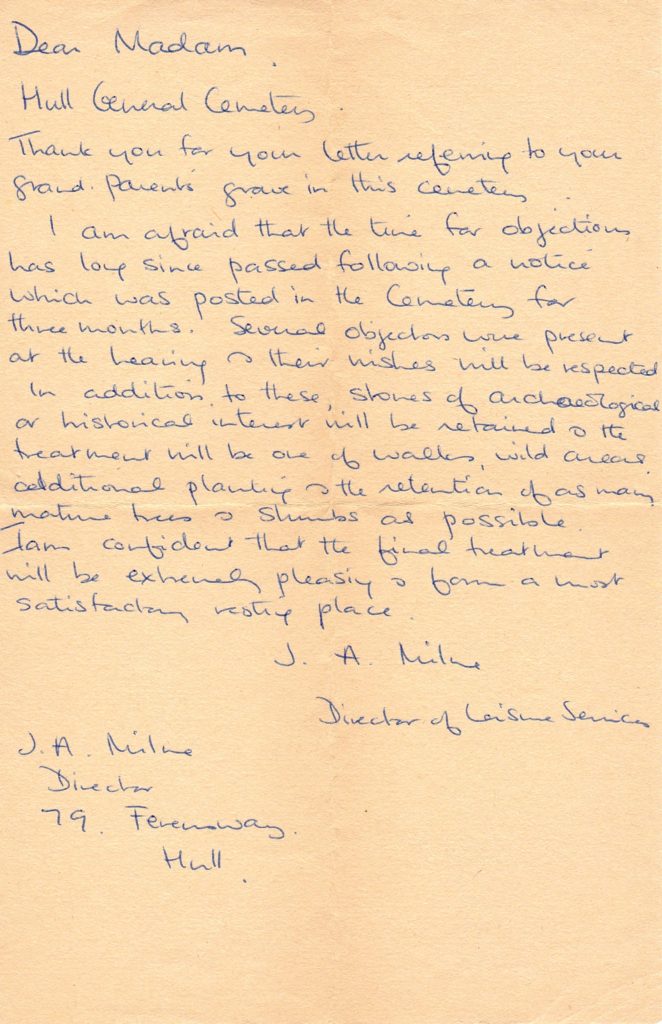

A hand written copy of a reply from the Leisure Services Department to one objector was made by Chris Ketchell. I include it here. It shows that decisions about the cemetery had been made prior to the Court’s decisions and indeed those decisions were to be drastic.

That the Council thought that posting a notice in the Cemetery for three months was sufficient notice is also open to question. Many of the people whose relatives were buried in there were old, possibly infirm and probably couldn’t visit their relatives’ graves, especially as the Cemetery was in such a state.

Let’s not forget that the Cemetery Company had made an obligation to the families of those who were buried in there, when the grave was bought, that they would maintain the site.

No, I think that pinning a notice up in the Cemetery at that point was not the best method to inform people of the changes afoot.

The Court result

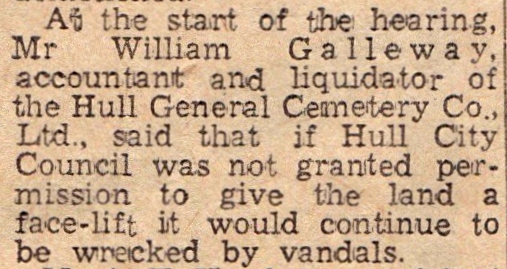

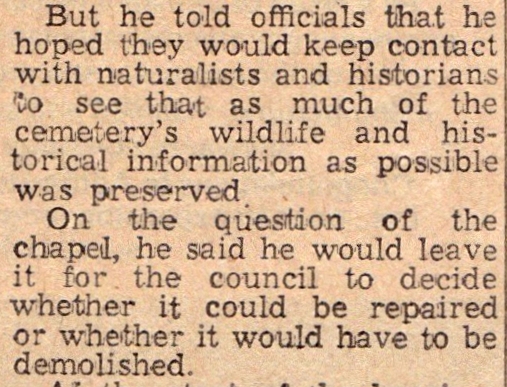

Unsurprisingly, with the Cemetery without ownership, the Company dissolved, the media speaking of it in terms of an ‘eyesore’ and ‘dumping ground’, and the general public seemingly uninterested, the Consistory Court approved the Council’s faculty bid. A flavour of the mood of the Court can be grasped by the comments of the Company’s liquidator and administrator at the time, Mr Galleway.

With such a ringing endorsement there is no wonder the Court took the decision it did.

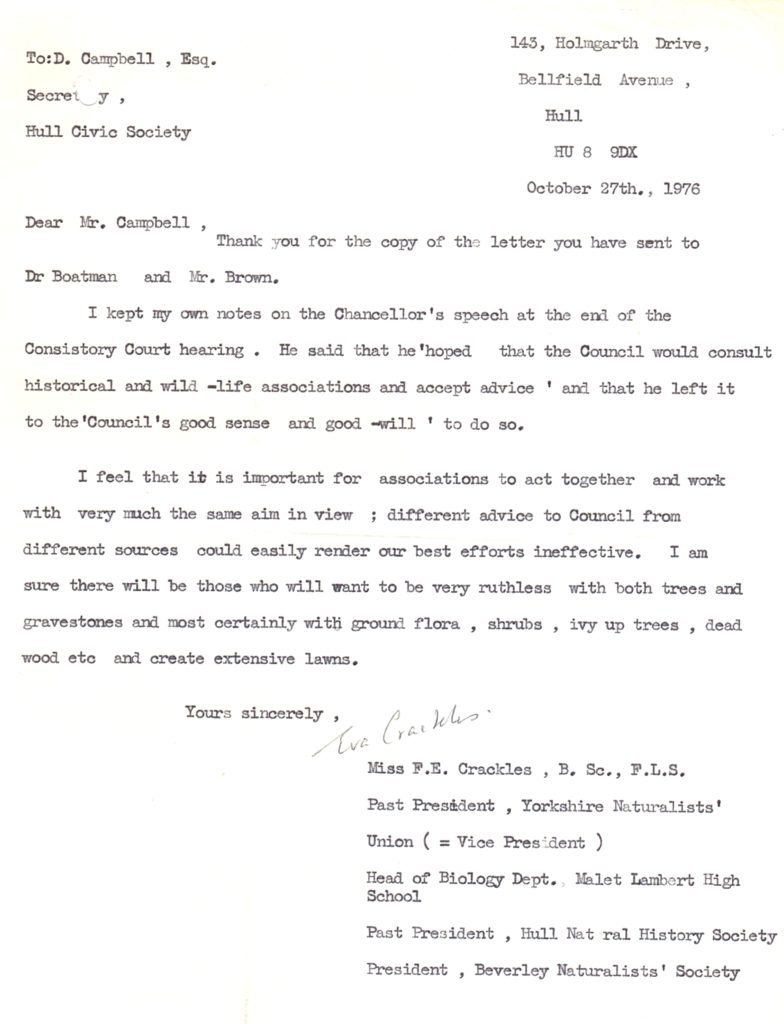

However, the Court was also moved by the objectors, not least the Hull Civic Society, who were vociferous in their opposition to the plans outlined by the Council for the site. Indeed they had put forward other options taking into account both the historic aspects of the site and eminent naturalists’ views, such as Dr Eva Crackles. As such the Court’s adjudicator, the Rev. Elphinstone, said,

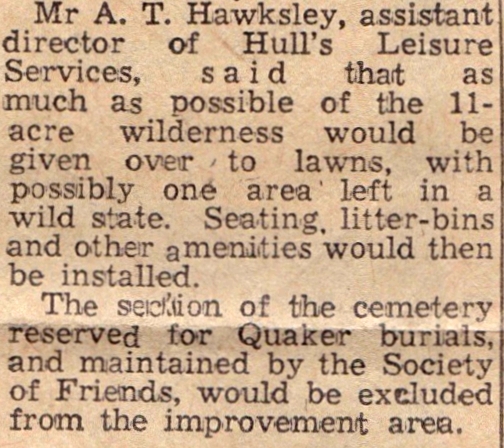

With the end of the adjudication Hull City Council were free to complete their task of developing the site. That plan was outlined by Tony Hawksley, Assistant Director of the Leisure Services Department, in the same article.

‘I love it when a plan comes together’, The A-Team

The problem was that the plan, especially in relation to the removal of the headstones, was so imprecise. Using terms like, ‘the removal of the majority of the monuments’, gave little to no indication of what that actually meant. What was a ‘majority of the monuments’? It was questionable whether anyone actually knew how many monuments were in there in the first place. To speak about a ‘majority’ of an unquantified number was ridiculous. Perhaps it heralded a more sweeping change for the cemetery.

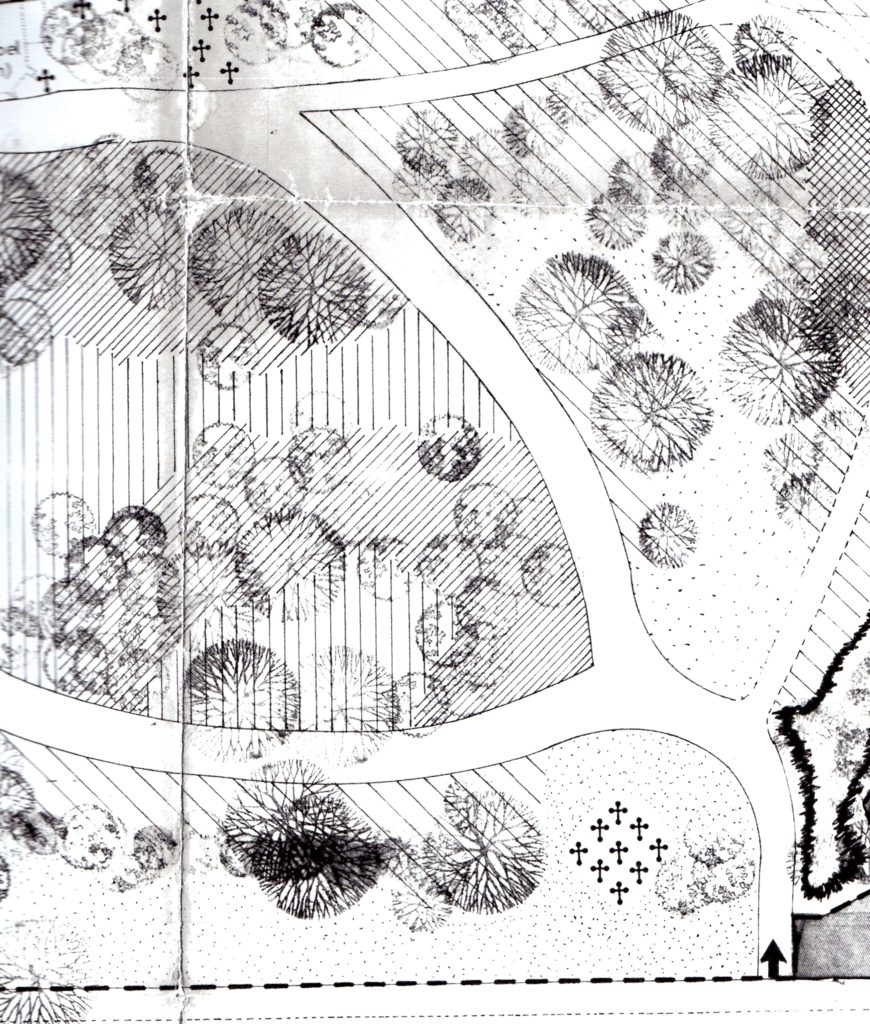

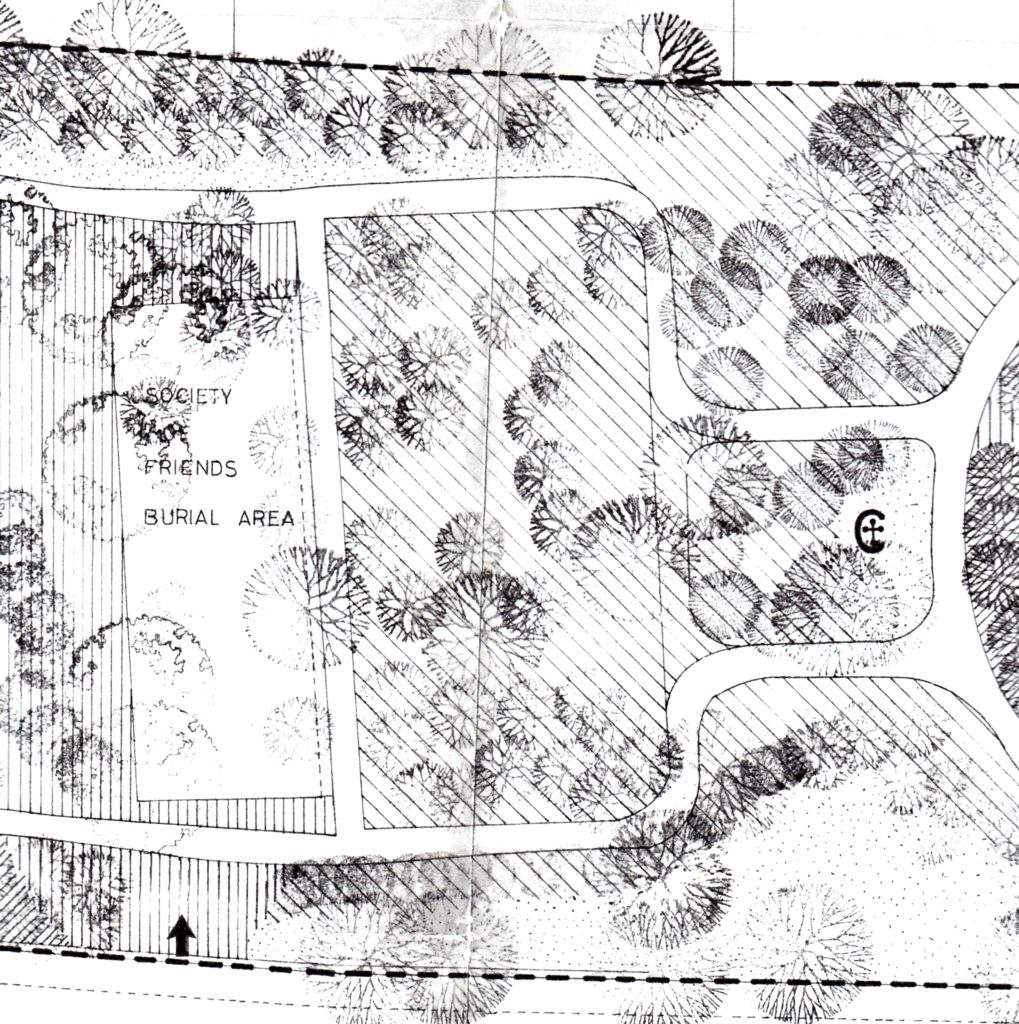

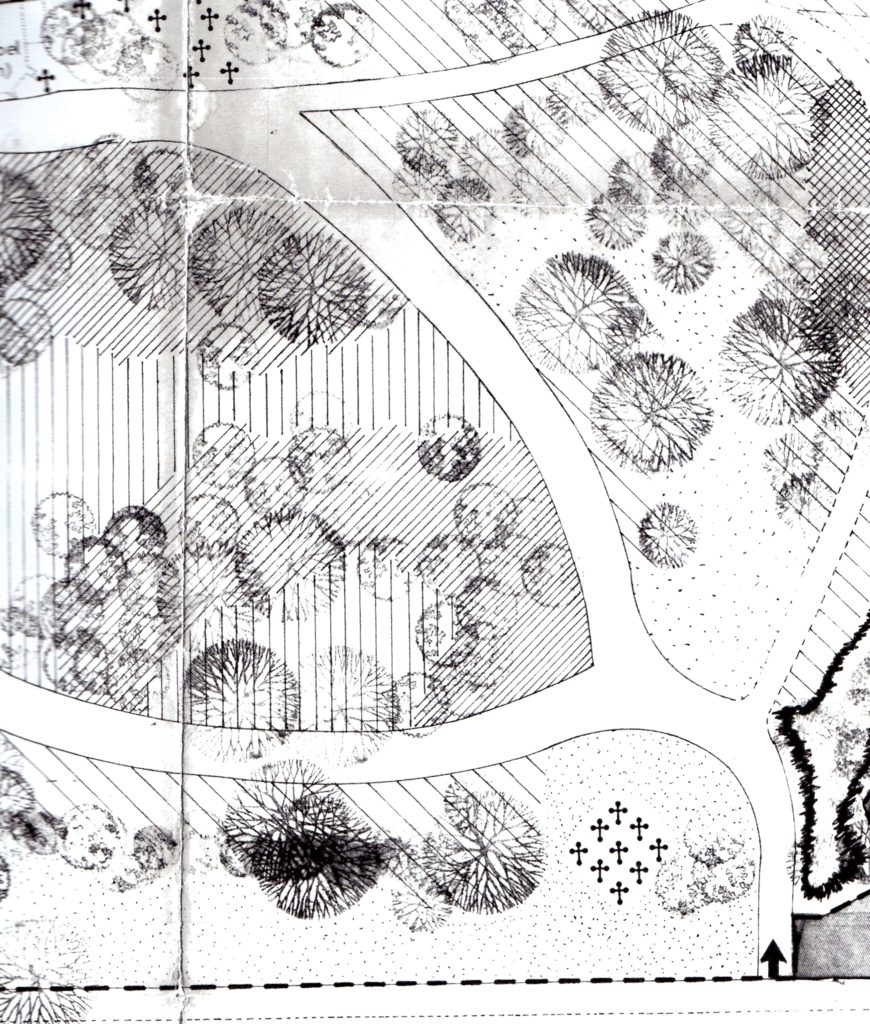

It wasn’t until December 1976 that a detailed plan of what was to be left and what was to be removed was drawn up. The results were shocking.

In essence, out of about 5,000 headstones in the cemetery, the plans showed that about 40 to 50 would be left. Two areas were to have headstones left in situ. One of these was the area known as Prim Corner. It held the last resting place of William Clowes, the joint founder of Primitive Methodism. Clustered around his tomb were a number of headstones of his adherents and supporters.

The second area that was to have stones left in situ was the area east of the ruined chapel as can be seen at the top of the plan above. This no doubt was to fit in with a nebulous plan for the chapel that the Council were deliberating on. That too is part of another story for another time.

It seemed like a good idea at the time

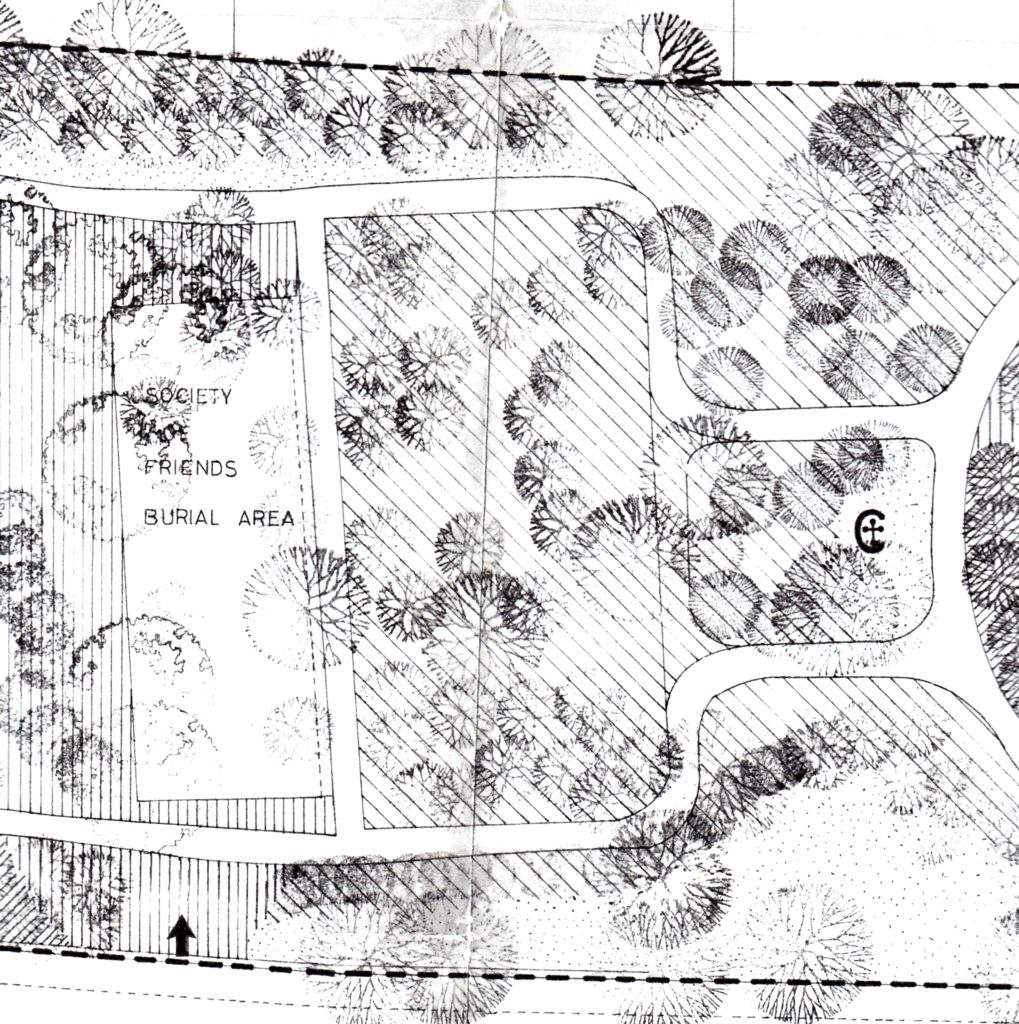

Finally, the Cholera monument, the large obelisk denoting the last resting place of some of the victims of the Cholera epidemic in 1849, was to be moved southwards on to a totally different area. The large C in bold on the plan below was the chosen site for this monument in the future. Of all the decisions made at this time one has to question the reasoning lying behind that particular idea.

And yet, none of this happened. What changed the minds of the planners?

The response

The Hull Civic Society, under the active leadership of its secretary, Donald Campbell and its chair, John Netherwood, wanted the Council to heed the words of the Consistory Court adjudicator. As such they began to muster support. Letters were sent to other interested bodies ranging from the East Yorkshire Local History Society to the Victorian Society.

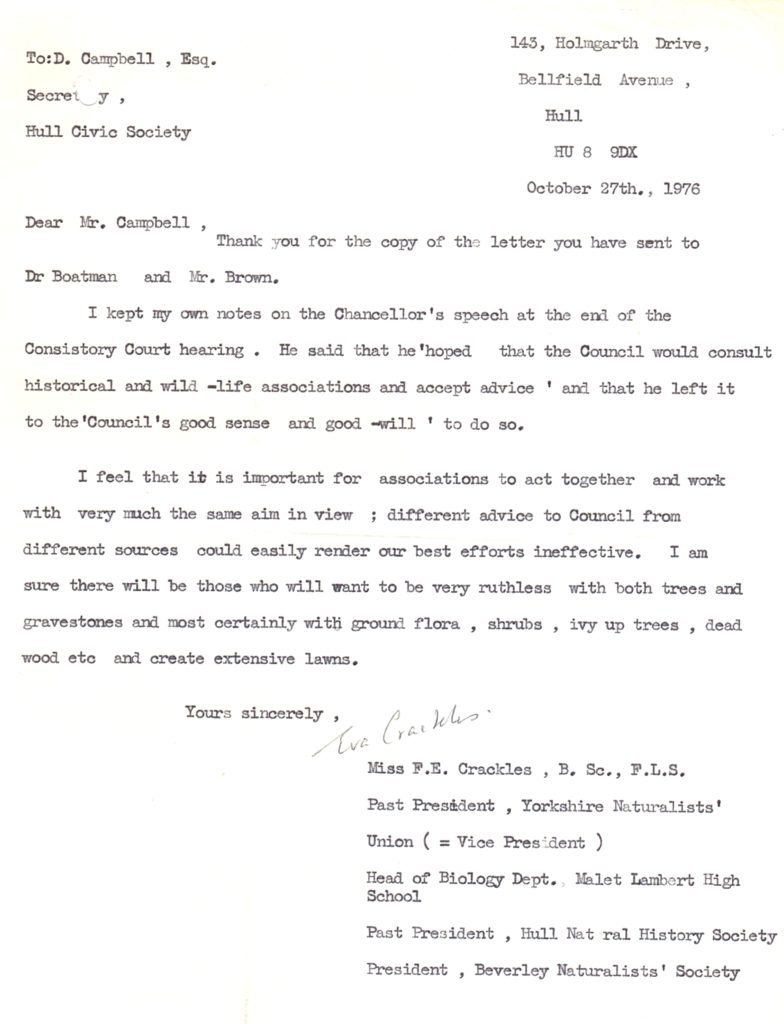

This rallying of support was not only confined to historical groups. Naturalist groups were also approached. The Hull Civic Society believed that the historic aspects of the cemetery were enhanced by the ones that nature provided. It was determined to protect the nature as much as the headstones. Dr Eva Crackles was approached. In her reply, having been at the meeting, she alluded to the Adjudicator’s comments,

Would the Council accept advice? As they had already outlined the plans for the site in the local press before the Consistory Court made its judgement that was unlikely. Still, hope springs eternal, as they say..

It is not a park. It is a garden of rest.

Correspondence between the interested parties continued for the rest of the year. The Council stating that plans had been costed and formulated. The objectors stating that these could be changed.

The Council offered the objectors the option, which they undertook, of meeting with the officers of the Council. These meetings appeared to be fruitful to some extent. The outline plan of removing the vast majority of headstones, and the large scale cutting back of the woodland, was said however to be non-negotiable.

The Town Clerk, in a letter to Donald Campbell, accepted that the Hull Daily Mail’s use of the term ‘park’ was not accurate. He said the idea proposed by the Council was to be more a ‘garden of rest’. The objectors accepted this was an improvement. The Town Clerk also went on to say that the site was still zoned as a cemetery and would be treated as such. This, too, was promising.

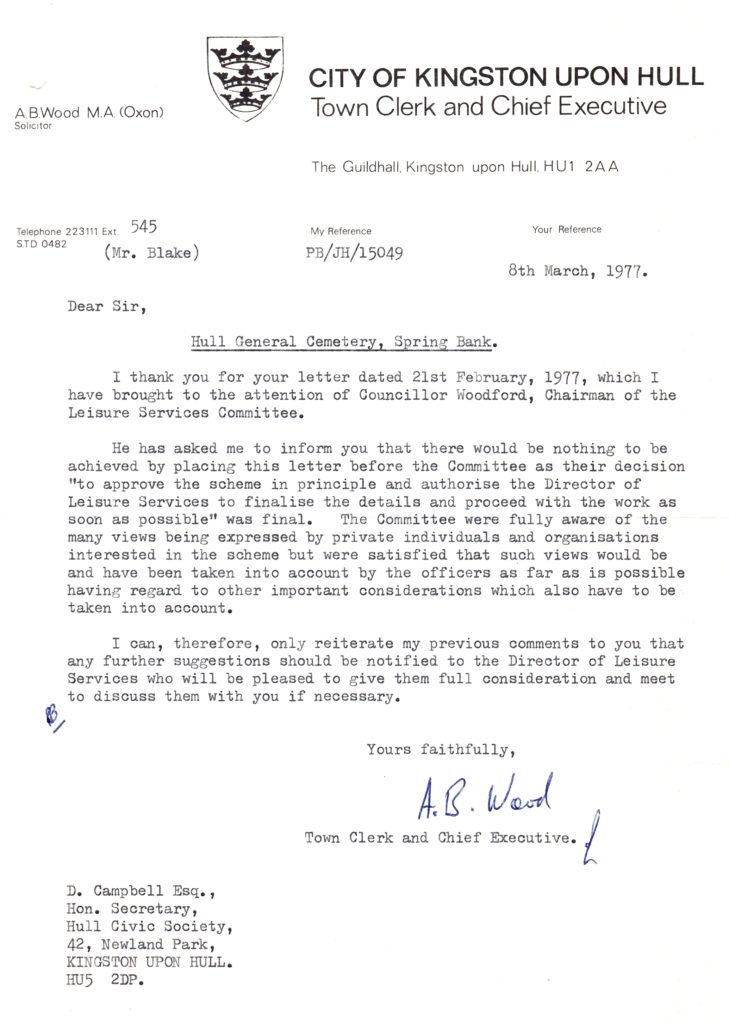

The representatives of the people didn’t want to meet the people

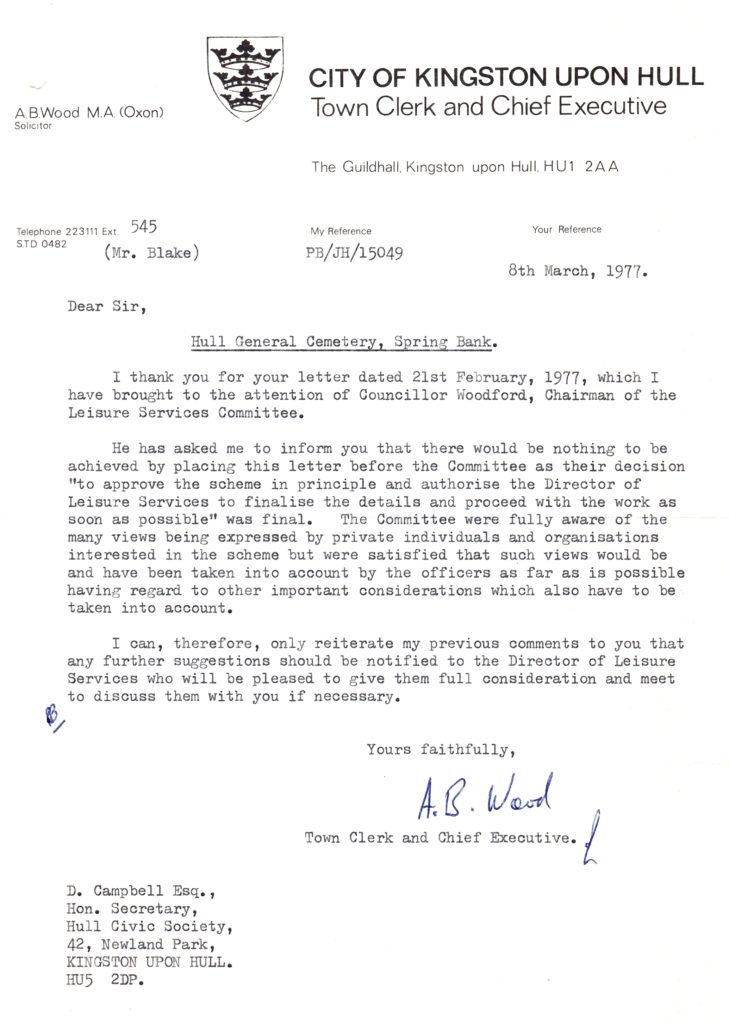

Finally, in early March 1977, the Town Clerk replied to yet another letter from the objectors, and invoking the Chair of the Leisure Services Committee’s words, it appeared the door was now closed to further suggestions.

So, in essence, the plans were set in stone. It was pointless to place the objectors’ views before the Committee. And anyway, the Chair and the Committee didn’t want to meet them. Now that wasn’t promising.

Enter an historian

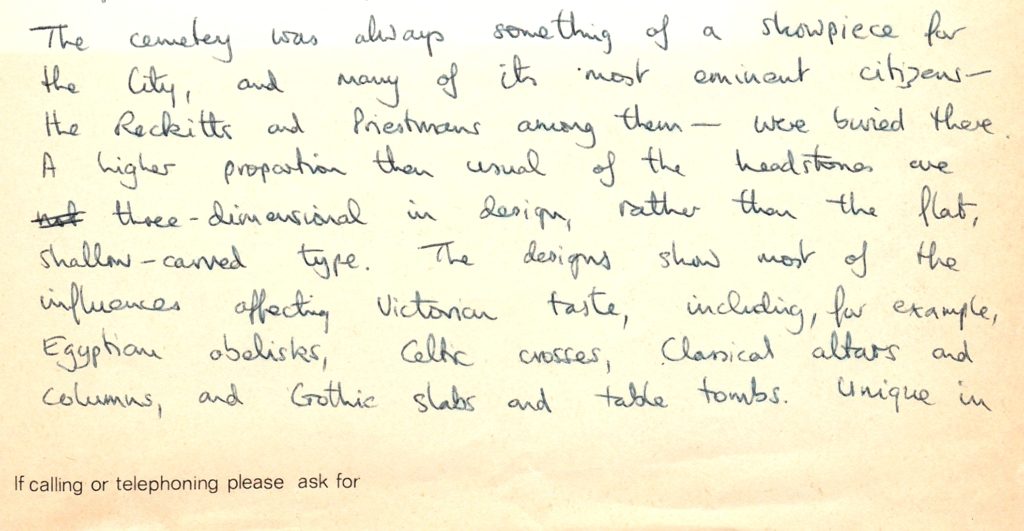

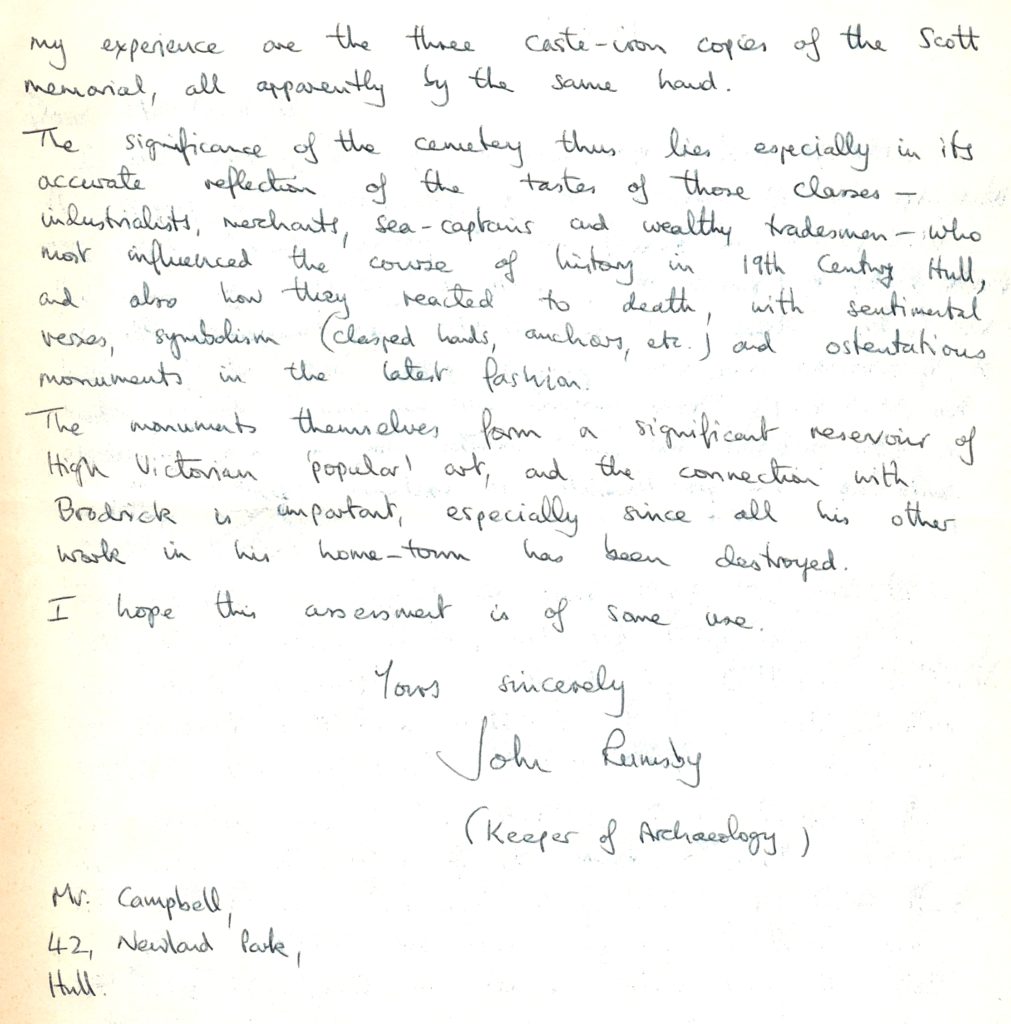

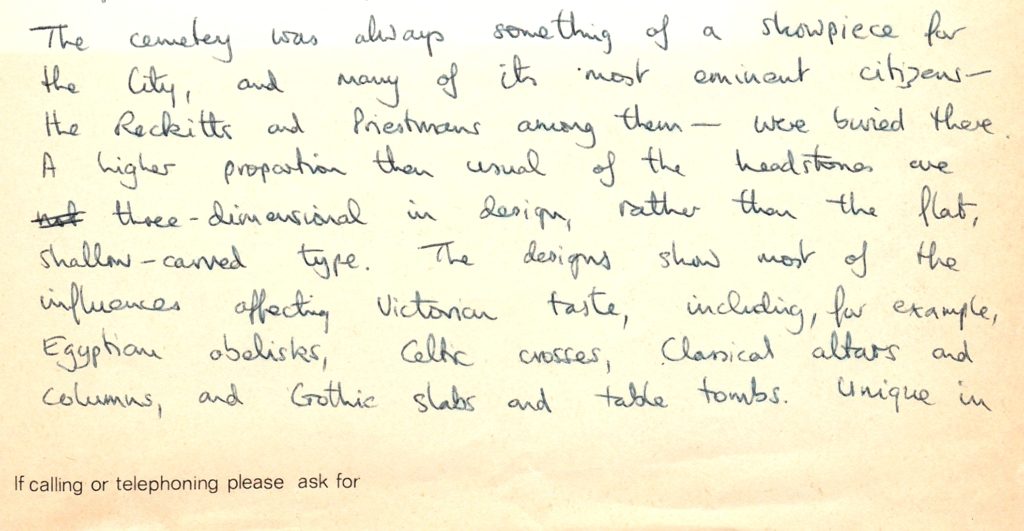

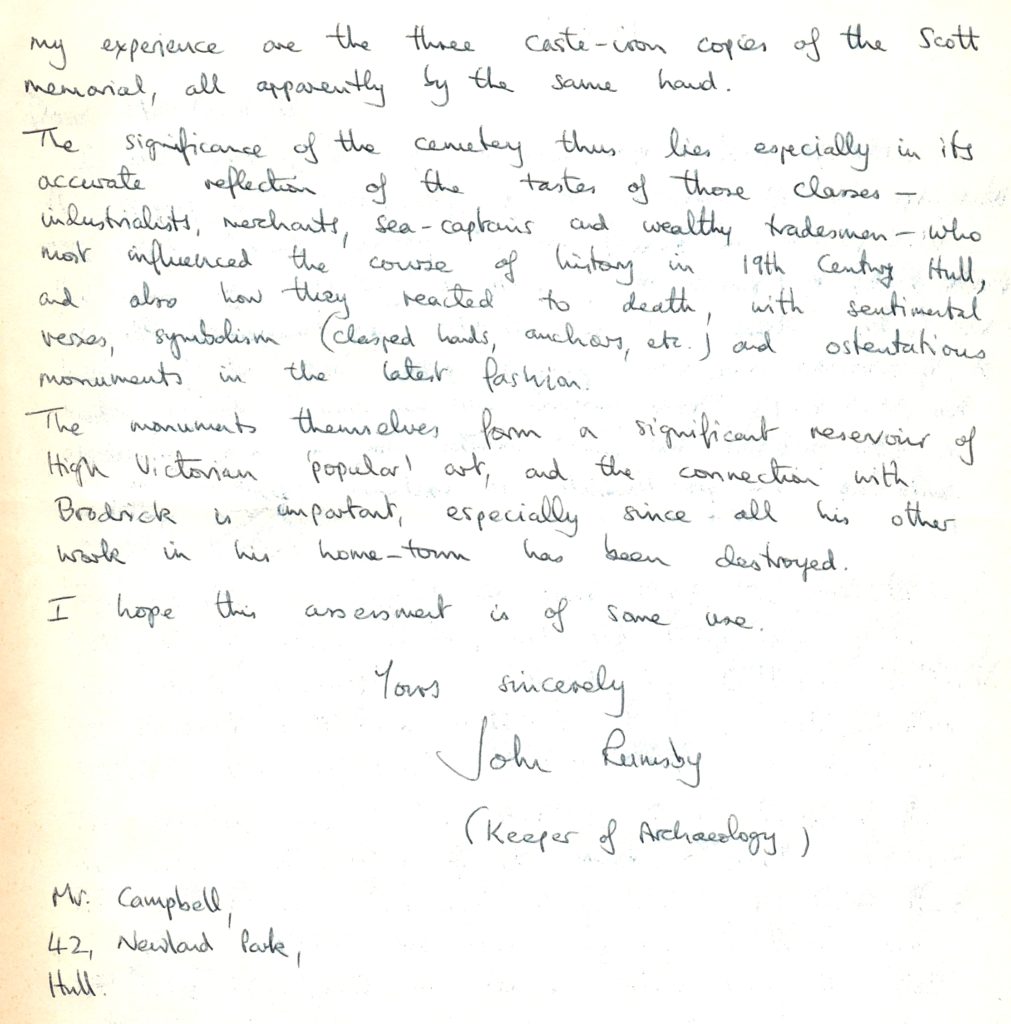

Providentially, a two page hand written letter arrived with Donald Campbell on the 13th of the same month. It came from John Rumsby, the keeper of archaeology for the city, and someone who worked for the afore-mentioned Leisure Services Department. The letter, reproduced below, outlined the beauty and uniqueness of the monuments in the cemetery.

Perhaps not all the officers were in agreement about the proposed official ‘vandalism’?

This letter, suitably anonymised, was sent by John Netherwood to the Council as evidence from an ‘historian’ as to the value of the headstones. Did this letter have some effect?

Probably not on the Council for its doubtful if they knew it had been sent. However, I believe it gave the objectors some heart and John Rumsby’s part in this story does not end with this intervention.

The Council were relying on their grant application being successful. The grant from the Department of the Environment would go a very long way to offset some of the costs in developing the site. The figure of £40,000 to £60,000 had been used in press releases. Concerns were now being raised as to what the Council would be able to do if that money was not forthcoming. The Council did not want the cost to fall upon the ratepayers.

The fight back begins in earnest

It was at this point that two more factors came into play. Both of them were connected.

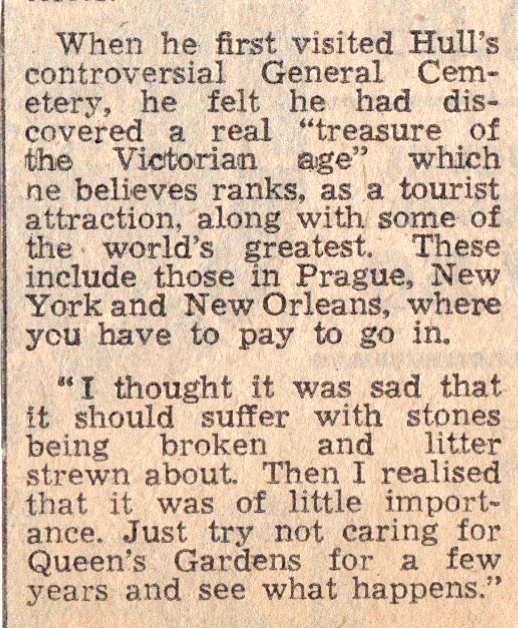

The first was that a lecturer at the Hull School of Architecture, Par Gustaffson, became interested in the plans for the Cemetery. Par was an architect from Sweden and he had come to Britain to work on the Byker Wall project in the north east.

Gaining a teaching post at the Hull School it is said that his lectures were legendary. They were so good the public often gate-crashed them. One student recalled that, ‘often one would find several old ladies in their best hats sitting on the front row’.

In regard to the Hull General Cemetery, Par, interviewed for an article in the Hull Daily Mail, in February of 1977, said that,

Par went on say, and in retrospect, his warnings ring as true today.

He said he had already contacted the Leisure Services Department with his ideas.

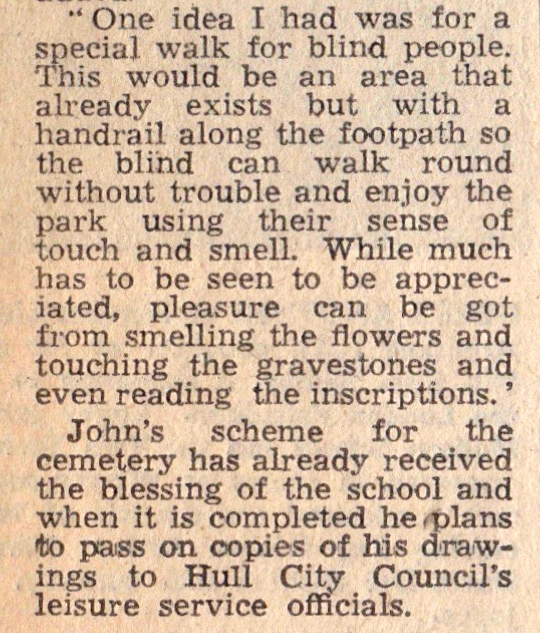

He also told the Hull Daily Mail that a final year student, John Waugh, had taken on the site as his final year project and had designed and incorporated many features that would enhance the site.

One particular feature was to have catered for the visually impaired. As John outlined this feature,

Unfortunately I have never seen a copy of John’s plans, nor was this aspect ever implemented. Could it have been implemented? Could it be implemented now?

But, as the article went on to say, the Council already had its plans drawn up as we saw earlier,

As The Hull Daily Mail went on to say, all of this depended upon the gaining of the grant from the DOE.

It also quite clearly stated that the plans of the Council were irreversible once put in motion and that the ultimate cost may well be paid in the future,

The second factor

Par Gustafsson, having worked at restoring Victorian cemeteries in his native Sweden, contacted the Hull Civic Society and other like minded people and organisations knowing that they were already involved. He also realised that the public needed to be mobilised before it was too late.

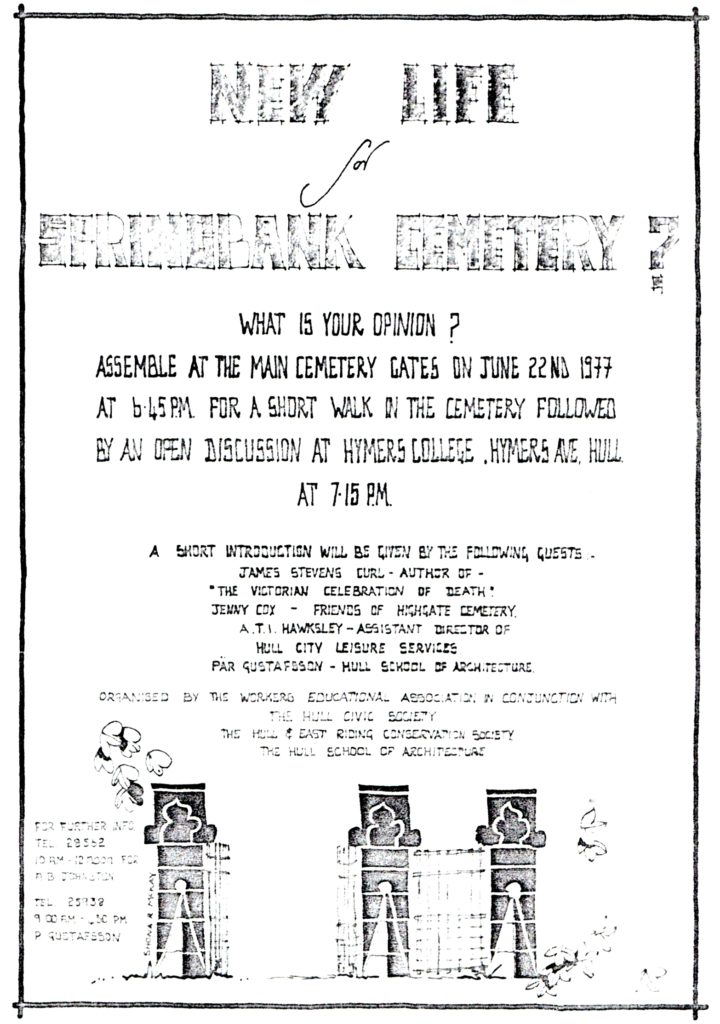

The first step to mobilising the public was to organise a public meeting and to call upon experts in their fields to assess the cemetery. When it came to experts, luckily he knew one or two. In fact the best in the business.

Another site visit but this time by experts

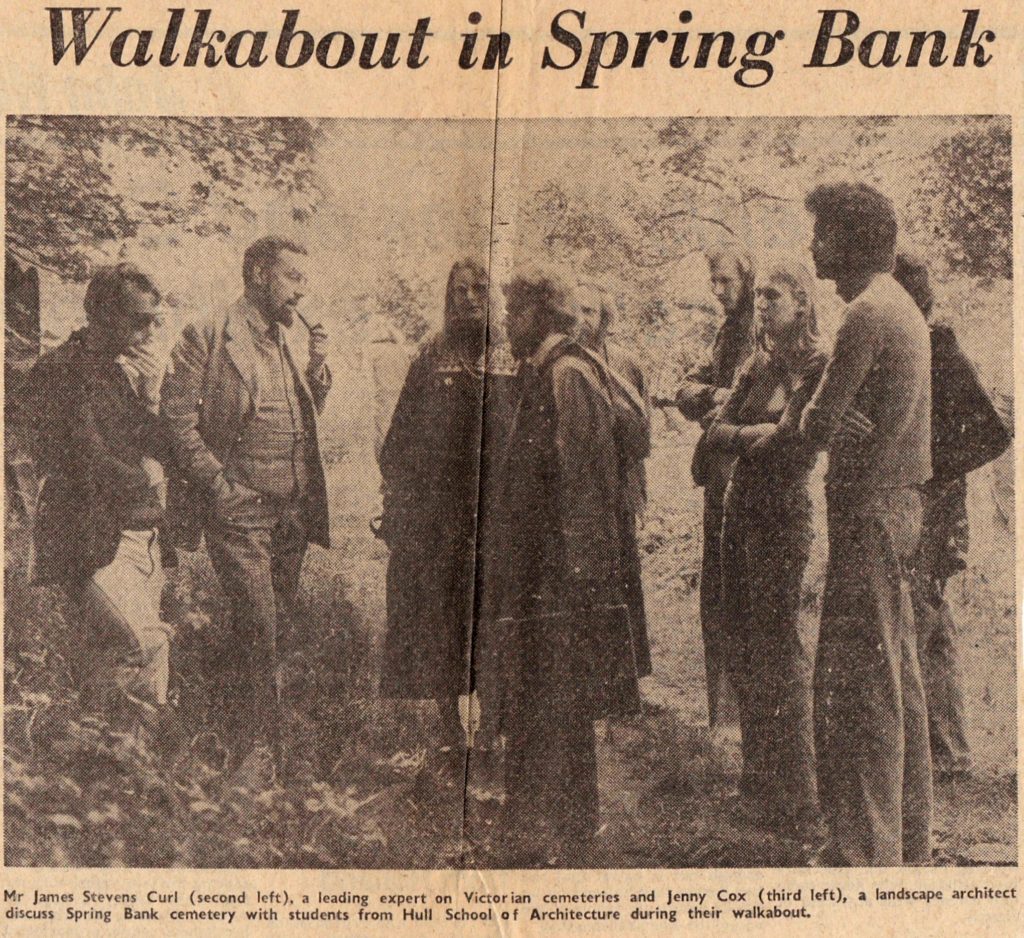

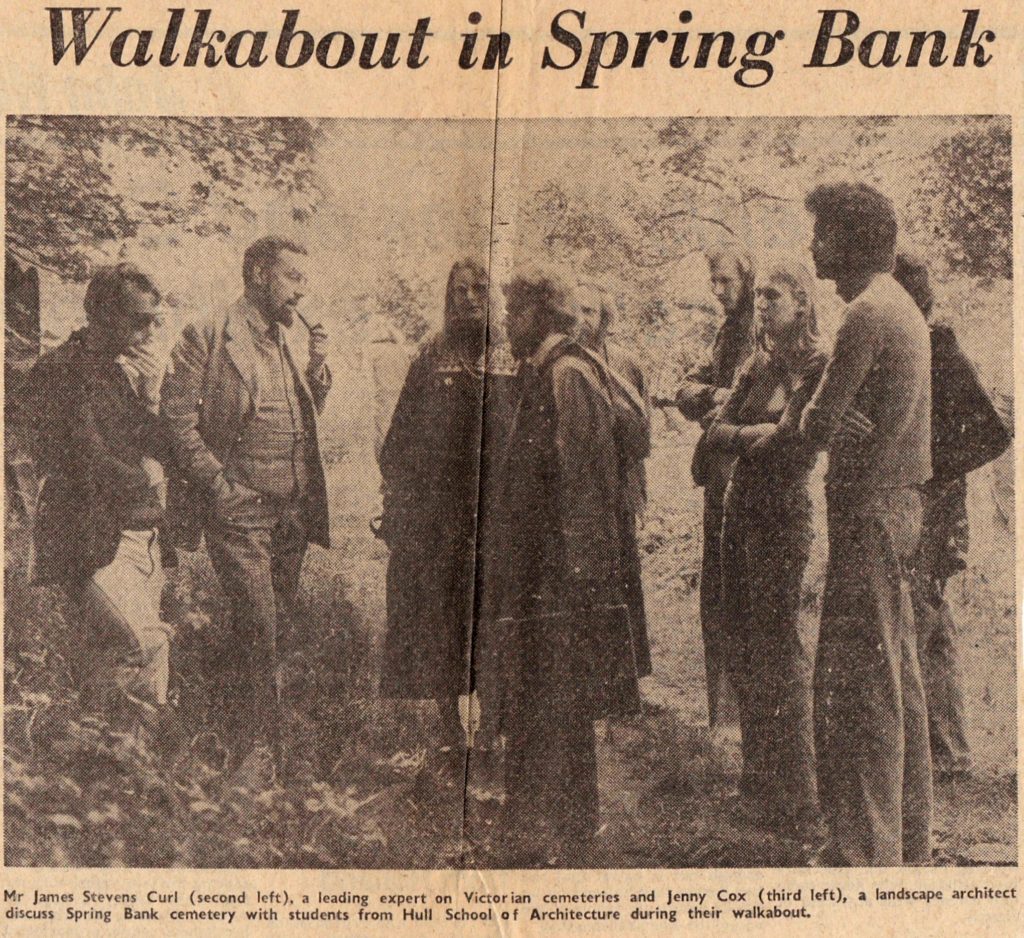

On the 22nd June a site visit was undertaken. Jenny Cox, a landscape architect with an especial interest in Victorian cemeteries and Dr James Stevens Curl, later Professor, a noted biographer of Victorian Cemeteries and Victorian architecture were the visitors. Accompanied by students from the Hull School of Architecture they toured the site. They later spoke at the public meeting, held that evening at Hymers College.

In his book, The Victorian Celebration of Death, published in 2000, Professor Curl recounts his and the Hull General Cemetery’s experience at this time.

‘Spring Bank Cemetery (by then extensively vandalised) was acquired by Hull City Council after the Cemetery Company went into liquidation in 1974, and it was proposed to clear the cemetery in the teeth of objections from the Friends of Spring Bank (who put forward less drastic alternative proposals), supported by the Victorian Society. The local authority went ahead regardless; most of the memorials were destroyed, and for good measure the boundary walls and cemetery offices were also demolished in an act of official vandalism of a particularly dreadful kind.’

Jenny Cox, the originator of the Highgate Cemetery plan, helped design and put forward the plan that Professor Curl makes mention of in the quote above.

This plan was rebuffed by the Council. They had already made their plans and saw no reason to change now.

The public meeting, arranged for that very day, attracted a large number of people. It took place at the Hymers College.

As can be seen in the copy of the flyer for the meeting, both visitors were to speak as was Tony Hawksley for the Council.

,

It was from this meeting that the Spring Bank Cemetery Action Group sprang. The group were unimpressed with the Council’s plans and mobilised in an attempt to thwart the plans the Council had put in place. Further meetings were planned and a determined campaign to enlist support from various sources, including celebrities, was put in motion.

However that is another story for another day.

The argument can be put forward that by this time it was far too late to materially affect the Council, and yet…

The power of the press?

On the 5th of July the Hull Daily Mail reported on the grouping later to be known as the Friends,

‘The City Council representatives present were given a clear enough mandate on what sort of finished result should be achieved’. The Hull Daily Mail were stating, in a more pleasant way, that the plans as put forward by the Council were not what the people wanted. In essence, they were told to go back and think again.

The idea of cost had been introduced by Campbell some time earlier in the discussions. He had pointed out that removing the headstones was a cost that the Council need not take on. He also pointed out that once the headstones were removed, and the area grassed, the maintenance costs would be increased. In essence, removing the headstones would increase the ongoing costs for the site. The logic was irrefutable. Not a good night for the Council.

The lobbying mentioned was also beginning to have an effect on the wider audience, if not yet on the Leisure Services Committee.

The local press were now questioning the validity of the plans, at least in terms of cost. This ‘cost’ could well fall upon the ratepayers and questions were being asked if it really was necessary. The Hull Daily Mail columnist, John Humber, was also sceptical and put forward in his column the idea of a ‘balanced’ approach to the development of the Cemetery site.

A change of heart or a change of mind?

A letter from the Director of the Leisure Services Department on the 21st July indicated a potential re-think on the part of the Council. Not a wholesale one, but a slight chink in the plans as shown above.

The letter began, quite plaintively, by saying that the Council hadn’t really wanted to take on the task of restoring the site, which was quite true. Now that it had taken on this role, it was a little put out that its plans were being objected to. There was an element of ‘hurt and misunderstood’ about the first paragraph.

So there!

It then went on to say that the plans were still open to discussion, something that the detailed plans, dated December 1976, and shown above, showed to be untrue. However, the change in tone in the local media had ruffled some feathers and this letter was the result.

It may be noted that the member of the Museum Staff mentioned was the same John Rumsby who had written to Donald Campbell earlier, and who, bravely, was also one of the attendees of the public meeting and spoke there.

Later still during this sorry saga, he was one of the signatories of the later petition against the ‘development’ of the site. A brave man indeed or perhaps just a principled one.

‘Points of detail’

So, the letter suggested that the ‘officers’ of the Leisure Services Department would be ‘receptive to suggestions on points of detail.’ Tony Hawksley, who wrote this letter, must have known that in putting this forward he was opening up the debate again. He may have felt that he was widening the debate a crack but the opposition would never be satisfied with that. But, to be frank, what could he do?

The issue may well have been done, dusted and dealt with in the Council chamber by December 1976, but that didn’t mean it was over in the wider world, as proven by the recent turmoil. Tony, being an experienced negotiator, also probably thought that due to the reception at the public meeting of the Council’s plans, a damage limitation exercise was needed. An olive branch here and there never hurt anyone, did it? Surely things couldn’t get any worse?

Still open to change?

About a month later, a letter from Mr Noel Taylor, the city’s chief planning officer, hit Chris Ketchell’s door mat. In it, Mr Taylor replied to a query from Chris regarding the possibility of the site becoming a conservation area. Chris had wondered if designating the site as a Conservation Area, in the legal sense, it then could provide some finance to develop the site more sensitively. Mr Taylor poured cold water on that idea. However, once again, the implication that the door was still open for modifications to the plans was put forward.

The ‘retention of some headstones of all types’ was a sea change from the paltry amount stipulated on the plan of December 1976.

The Chief Planning Officer was now making the same argument that the objectors had been making, with regard to ‘class divisions of Victorian society’ being highlighted by ‘retention’ of some of the headstones. This must have been music to the ears of the objectors. It mirrored Campbell and Rumsby’s points that they had put forward in the past. A ‘sea change’ indeed.

It was now early August. The temperature of the debate was about to rise.

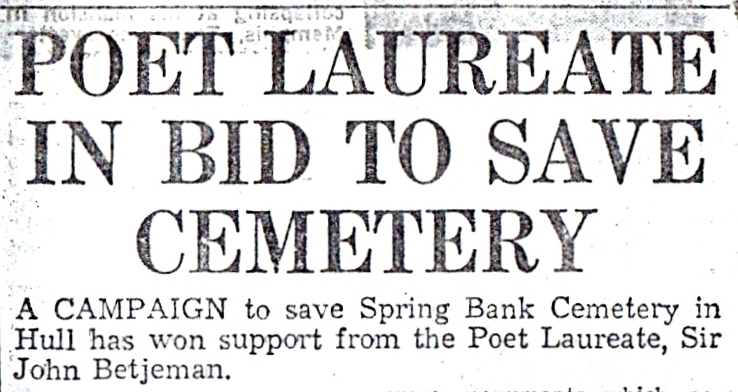

Dead Poets Society

The very next day, this parochial debate, about what to do with a derelict cemetery, reached national proportions.

Philip Larkin had long been the friend and neighbour of Donald Campbell. Campbell had written to him as early as July 1974, on the issue of the development of the site. Larkin replied saying that he remembered visiting the site in 1955, when he first came to Hull and he thought it, ‘was a uniquely beautiful spot in which I spent many happy hours.’ He went on to say that,

‘I don’t know precisely what kind of support you think I could give (I am not very good at arguing with people, as everyone in this university will know) but I do think that the burial ground as we knew it was a remarkable relic of nineteenth century Hull and if it could be restored to its former beauty that would be the best course to adopt. If not, then let the current abandonment of it to hooligans cease.’

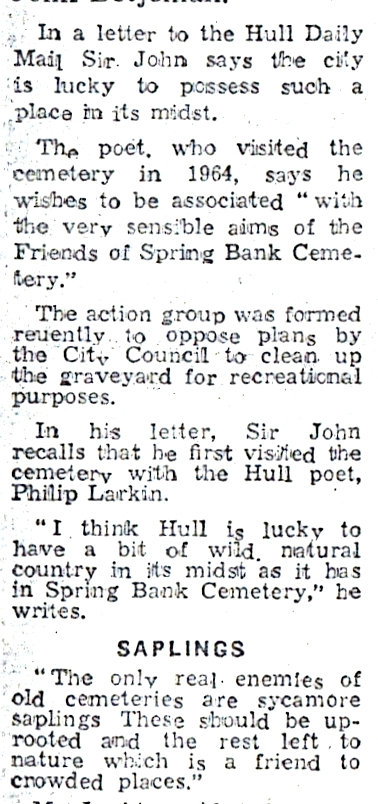

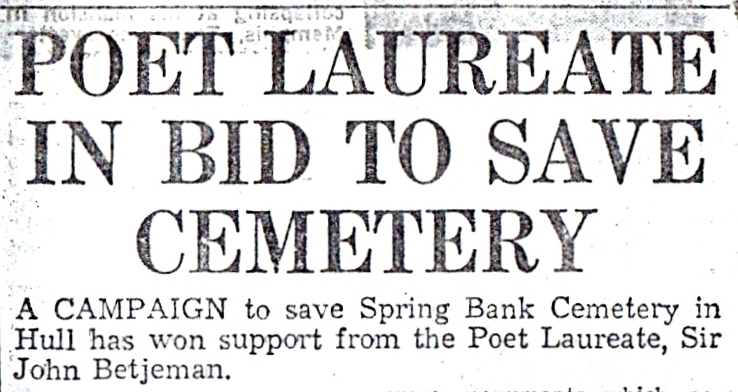

Poet laureate

Some 11 months later, Campbell wrote to Larkin again. Campbell asked if he would attempt to enlist the Poet Laureate, Sir John Betjeman, to support the campaign. Larkin wrote to Betjeman and Sir John said he would support the campaign.

On the 17th August the Hull Daily Mail, as well as a number of national newspapers, printed the story. The Hull Daily Mail used the following headline,

The article, which must have caused some anguish in the Council chamber, went on to state,

Well, no one had said before that the city of Hull was ‘lucky’ to have the Hull General Cemetery. Especially as it was, in all its splendid dishevelment. Surely the prevailing idea put forward was that it was an ‘eyesore’ and an embarrassment. The Council would address this problem in the future. It was this argument that would hopefully get the money from the government. The eye of the beholder is surely multi-faceted.

This intervention, on the part of two cultural icons, and on a national scale, was not in the script that the Council prepared. It really didn’t need this, not at this time.

Remember the DoE was still to rule on allocating the necessary grant money that was needed to put the Council’s plans in place. Bad publicity for the project was never to be on the agenda. Ignoring the wishes of a few like-minded ‘weirdos’ was fine and their objections could be brushed off. Not so the views of two of the most famous poets in Britain at the time. Time for a little back-tracking.

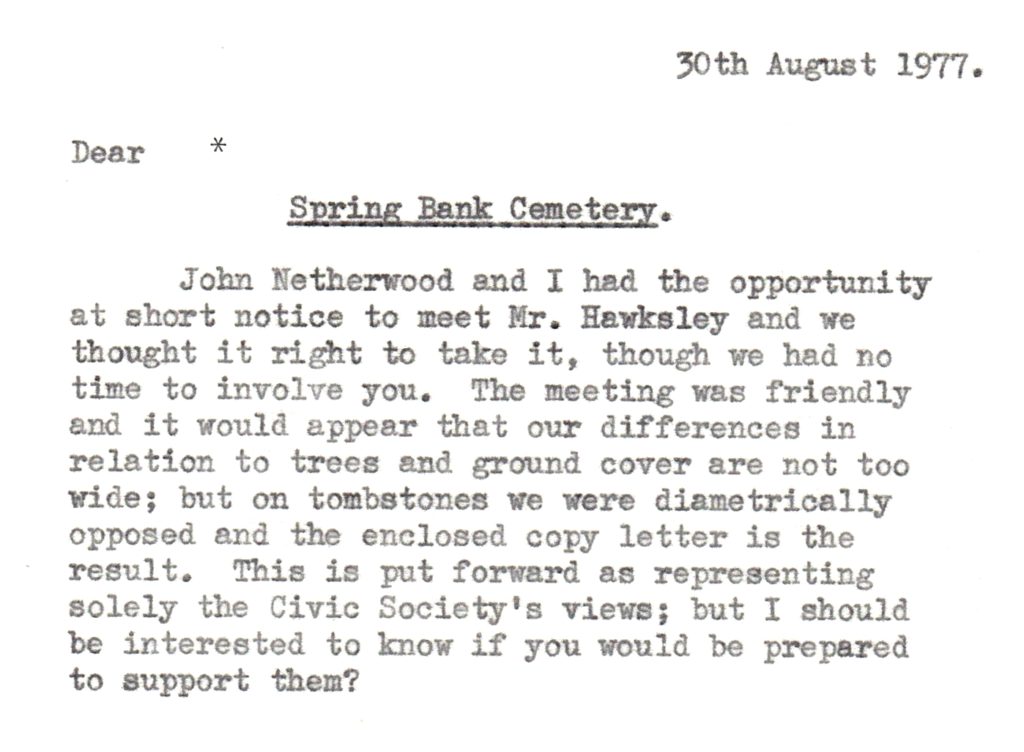

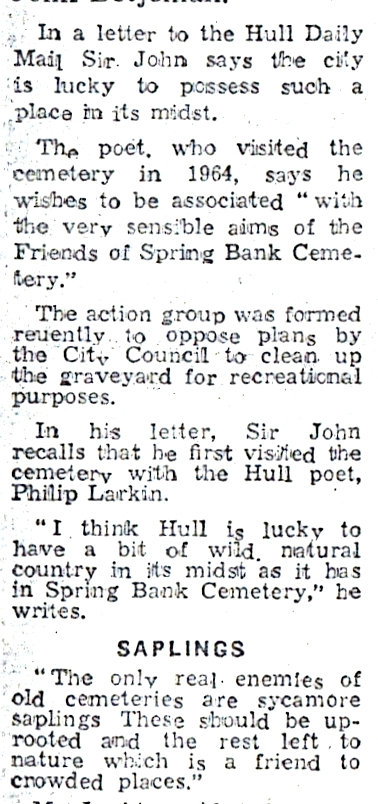

Another olive branch

The Council decided to offer a meeting. Not with the Leisure Services Committee. That could be viewed as conceding a point or two. No, a meeting was offered, but with the Director of the Leisure Services Department. A step in the right direction.

This took place on the 23rd August 1977. Donald Campbell and John Netherwood from the Hull Civic Society were invited to meet Tony Hawksley to try to resolve the differences that had arisen. Tony was only the Assistant Director but, for all intents and purposes, ran the Department.

Donald sent a letter to the members of the other interested parties on the 30th, describing how he saw how the meeting had gone.

So, how far apart were the two sides at this time?

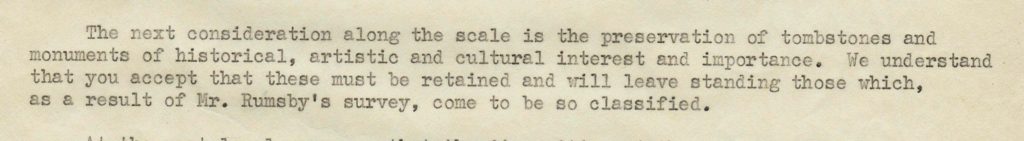

We have seen a weakening of the position of the Council over this period but, as the letter above shows, the plan was still to have a wholesale destruction of the headstones.

Never the twain shall meet

Donald Campbell wrote to Tony Hawksley on the same day, outlining where the differences lay. Its worth looking at this letter in detail. Betjeman and Larkin were not the only ones who could soar poetically, but it also lays out quite clearly what could be lost forever if the Council failed to listen.

The indication here was that the Council were now being guided on headstone retention by John Rumsby which was a positive point. At least the headstones were being evaluated on their historical importance and artistic value rather than, as evidenced by the previous plan, how nice they looked in a group at certain points on the plan.

Cemeteries are depressing

Campbell then attempted, as I’m sure he did in the meeting, to point out the inconsistency and subjectiveness of the Council’s previous plans for the site.

One can’t help but applaud Campbell’s poetic use of language here.

And of course he is right. Thomas Gray’s, ‘Elegy in a Churchyard’, written in the 18th century, surely could have refuted this narrow parochial view of a cemetery as being depressing. Having met Tony Hawksley a few times in my working life, and he was a likeable chap, I can only suggest that he had reached a point in this discussion of having no other argument left and had to fall back on the old tired formula of cemetery equals grief and depression, therefore not enjoyable.

This line of argument I suppose can be excused to some extent. After all a cemetery can be a place where grief can be pervasive.

A lack of vision

However, what cannot be excused, is that the Council failed to grasp the significance of what they had to hand in the cemetery. It is sad that our local Council, in the face of expert advice from within and without, could not raise its gaze to look beyond its narrow plan and seek inspiration from the sensitive development of Highgate and Kensal Green. This really was a ‘once in a lifetime’ chance to preserve something that could not be replaced.

The problem, at least to my eyes, was how ‘progress’ was seen during that period. ‘Progress’ was usually defined as destroying something old, only to replace it with something new. So to destroy much of the cemetery’s habitat and headstones had to happen, if ‘progress’ was to occur. And ‘progress’ was defined by lawned areas. A poverty stricken definition of progress in my eyes. It’s not an approach that has necessarily gone away. However, it is a lot less evident these days and when it does occur it gets the response it deserves.

Another poet?

Campbell went on to say, and in my eyes, probably reached even more poetic heights…

The words paint the picture so clearly. The masterpiece was in danger of being lost; the magic at risk of being thrown away into the skip. If only the people with the power could be convinced of this argument, if only they could see what he could see.

He ended the letter with this plea:

Deaf ears

In response to this impassioned plea he received a brief letter. This said that his request for the survey results the Council had undertaken of the local residents was enclosed. This survey was supposed to show that the ‘public’ wanted the Council to go ahead and deliver on their plan.

This survey has not been seen by me so I cannot judge it. I do know from reports in the press that only 51 people responded to it. Of them, only 25% wanted the site fully cleared in accordance with the Council’s plan. So 13 people in the area, and I’m giving the Council the edge here in numbers, supported the plan. Hardly representative. Remember the historical clearing of the municipal cemeteries of their kerb sets and the notice hanging in Hull General Cemetery? Numbers only matter at election time. As long as you have been seen to do the ‘right thing’ and ‘follow the procedures’ there cannot be any backlash. The public were consulted and their views were taken into consideration; all 13 of them.

Hull City Council, at the time, had a way of working. Although appearing to take the public’s views into account, it was often skewed to get the result it wanted. And I’m quite sure that it did not differ from any other large municipal authority of the time.

A better response but little movement

A fuller response to Campbell’s letter arrived on the 16th September. In it Hawksley defended his idea that cemeteries were depressing places but went on to say,

Its interesting to see that the original plans that the Council had for the site did not include giving such plants mentioned above free rein and ‘dominance’. Those three species, the ‘usual suspects’ of sycamores, brambles and ivy are still there. Thriving. Sadly many of the other species and, of course, many of the monuments are not. That didn’t work out quite as planned did it?

The cheque’s in the post

The Hull Daily Mail of the 30th September reported the news. ‘Tidy Up Grant for Cemetery’ was the headline and a few days later, on the 13th October, it reported that the final figure granted was £64,000.

But hang on, didn’t I see something in an earlier edition of the newspaper that work had already started?

That’s true. As soon as news that the grant had been secured on the 30th September work began on site. Even the normally servile Hull Daily Mail appeared slightly suspicious using quotation marks around part of the headline. The Council were certainly quick off the mark. Had they reached the point were they just wanted to get the whole thing over and done with now that they had the money? Let’s face it, it had been one headache after another.

The librarian strikes back

The following day Philip Larkin sent his letter of support for the Cemetery’s survival. He was arguing for a less draconian format than the Council had planned.

Larkin said in his letter,

‘The important thing is, as I see it, that whatever time and money the Council proposes to spend on the cemetery now should be devoted to preserving its character; first, by tidying it up, secondly by restoring and re-positioning all memorials that are not smashed beyond redemption, and thirdly by providing it with an unclimbable wall or fence that will enable it to be locked at night. To remove the graves, the trees or even the undergrowth in an attempt to impose on it a municipal respectability would be a disaster. The place is a natural cathedral, an inimitable blended growth of nature and humanity of over a century, something that no other town could create whatever its resources.’

Unfortunately, the letter landed upon the stolid desk of ‘municipal respectability’; Councillor Harry Woodford, the chair of the Leisure Services Department. Not a poet by nature, and I would suggest unlikely by inclination, to him such entreaties fell on stony ground.

Woodford’s reply was brusque to the point of being insulting.

‘Dear Dr Larkin,

Thank you very much for your letter of the 11th October, 1977 on the subject of the Spring Bank Cemetery. I am pleased that you have taken the time and trouble to write to me and am very grateful for your interest. I will of course record and note your comments along with all the other letters and comments I have received on this subject.’

If he had written at the end, ‘and don’t call us, we’ll call you’, it couldn’t have been any more blunt in its dismissal.

The objectors had probably managed to get as far as they could go. They had done well in the limited time and with the limited weapons they had. If the site was to be saved from wholescale destruction it all depended upon the site visit of the Leisure Services Committee – under the guidance of its chair, Harry Woodford.

In the immortal words of a later politician, ‘the world has had enough of experts’ and that’s exactly what the councillors of the committee probably thought. No outside experts were needed here. What could possibly go wrong?

The Site Visit

And so we arrive at the day the members of the Leisure Services Committee visited the site. The image at the top of this posting is taken from the Hull Daily Mail of the 27th October. I can name one or two people in the photograph. I’m sure others could probably name more.

The man declaiming in the centre is the Assistant Director of the Leisure Services Department, Mr Tony Hawksley. A thoroughly nice man, at least in my dealings with him as a union rep. He was blessed with a good sense of humour, which always goes a long way with me. Tony had also risen through the ranks from apprentice gardener up to the dizzy heights of No.2 in the department. He fully understood that he implemented the decisions of the Council; he did not make them.

To the extreme left of the scene is Dave Wilkinson. He was the manager of the Leisure Services western half of the city, into which Hull General Cemetery was about to fall. His view of the site, as he told me at the time, was simple. He would, ‘level the site and grass it all’. I’ve modified this sentence for the faint hearted. Dave, too, had risen through ranks. He knew the score and what was expected of him.

As you can imagine, a plain speaking man. He once vaguely complimented me. In some tense negotiation I once said to him that the workforce weren’t happy with something or other, and changes needed to be made, otherwise there may be some disruption. He leant back in his chair, fixed me with his gimlet stare and said, ‘Pete, your members are behind you like Scotch mist. They’ll disappear once the sun comes out. You’re a bright lad, don’t waste your time bluffing me. Now let’s get on.’

He was right of course, about the Scotch mist part. I learnt that later, in another dispute but that’s another story. He may have been right about the ‘bright lad’ bit too, but it’s too early to tell yet. I’m only into my seventieth decade, but I’ll keep you posted. O.K.?

The Chairman

To the right of Tony Hawksley is a short and stout man. This is Councillor Harry Woodford. The archetype of the gruff, self-made man who won’t tolerate any nonsense. He could have been created as a character in any of J.B Priestley’s work. Whenever I saw him the phrase, ‘Where there’s muck there’s brass’ sprang into my mind. He would probably have fitted in to the Victorian period better than the modern day, but an effective politician nonetheless.

Peeking out from behind Hawksley, is, if my memory recalls, Councillor Nellie Stephenson. I may be wrong here as I had little to do with this lady. I only met her once and that was well over 40 years ago.

Who’s the person in the nice suit and tie? He’s standing just behind Woodford and staring intently, if not murderously, at Hawksley? Why it’s a young man you may have heard of before. His name was Chris Ketchell.

What petition?

Prior to this photograph being taken Woodford was presented with a petition. The petition’s aim was simple. It wanted to restore the site as sensitively as possible with no removal of the headstones. It had been started in the August and now, two months later, had garnered over 5,000 signatures. A far cry from the survey undertaken by the Council.

So the site visit went ahead. The councillors ‘investigated’ the issue.

Well, as much as they felt they had to. The result of this investigative trip was a foregone conclusion, as evidenced by the press release the next day.

The plan to remove the majority of the headstones was to go ahead. However the question what the term ‘majority’ meant had come a long way. Without the campaign that was waged, it would have been more destruction. Of that there is no doubt.

Today, there are now just over 1,000 of the original 5,000 headstones and monuments left on the site. 80% lost. A sad indictment on a council department more used to handling bowling greens and swimming pools than history. On the plus side we still have 20%, and for that we must thank Donald Campbell, John Netherwood, Par Gustafsson, Chris Ketchell, John Rumsby and many others.

Look on my Works, Ye Mighty, and Despair!

We are left now with the consequences of that short sighted action by the Council almost half a century ago. Long gone are the ‘lawned areas’. Nor are the ‘sycamores, brambles and ivy’ constrained. Indeed activities constraining such plants are frowned upon in some quarters. Fashions change, and not just in clothing.

So, perhaps it’s time to ask a relevant question. Where now, in Hull General Cemetery, are any elements of the original plan as approved by the Leisure Services Committee that bleak October day back in 1977?

Not much. Some of the planting survives along the northern and southern edges of the site. The benches that were sited were destroyed by fire and vandalism. No litter bins ever appeared. The paths, which I vividly remembering maintaining with dumper loads of gravel, are now quagmires at this time of year. The lawned areas, once favoured spots for families to picnic and play, are now covered with brambles, ivy or cow parsley. The proliferation of sycamore and ash saplings is probably at the level it was prior to the clearance in the seventies. I would guess so is the ivy. I do not remember in the past, and the site has been in my personal past for a very long time, the ivy being so strongly wedded to some trees that it brought them down, but it does now.

Surprisingly, the most constant factors that the original plan featured, are the mature trees and the headstones. Ironically, it was some of those things that the original plan wanted to remove. I suppose it just goes to show that there’s still life in the Hull General Cemetery. If you know what I mean.

Protect and survive

It’s at times like this that the desire to have a time machine grows. I would love to whisk the Leisure Services Committee from their site meeting back in 1977 to today and show them the site now. I think I would enjoy it, but I don’t think they would. Knowing them, they would probably be thinking, ‘we could have used that £60k on something else if this is what we ended up with.’

But I don’t have a time machine, so it’s only us today who can harbour regrets about what happened all those years ago. The clock can’t be turned back; we cannot rescue what we’ve lost. What we can do though is conserve and protect what we have left. Surely we owe that to the people who took on the Council back in the seventies.

As Donald Campbell said in his letter, ‘We owe it to future generations not to destroy the magic’. My children enjoyed the ‘magic’ of the site as they grew up, and my grandchildren are doing that too. And sometimes, when I’m in there, I can still feel a little bit of that ‘magic’ rub off on this tired old man.

So yes I think it’s something worth fighting to preserve. What do you think?

I wrote an article six years ago about the events leading up to the founding of Hull General Cemetery. In it I quoted words from Joni Mitchell’s Big Yellow Taxi. ‘You don’t know what you’ve got ’til it’s gone’. We lost something back in 1977. What we have left is neither the ‘dream plan’ that the Council of that time envisaged, nor is it what was destroyed. Like many compromises it just feels a bit ‘second best’. What a shame.

Postscript

I was leaving this story with the sentence above. However, a chance find by the volunteers yesterday, February 27th, prompted me to add this part. The volunteers had found a part of a headstone. A small part with just enough letters remaining so that Bill Longbone could identify who it had belonged to. It was a fragment of what must have been a larger headstone. It wasn’t found in the Monumental Inscriptions books that the East Yorkshire Family History Society produced. It was a ‘lost’ stone for a ‘lost ‘ family.

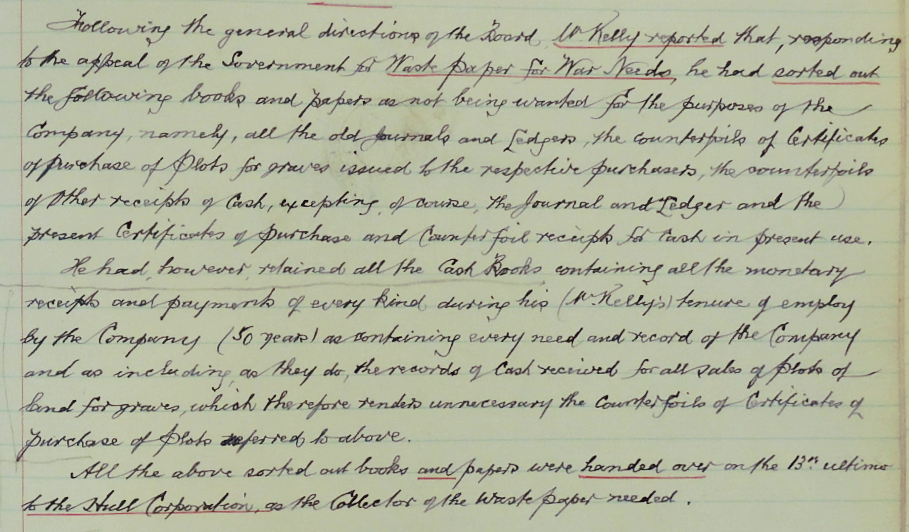

Now this remnant and indeed quite a few other headstones have been found by the volunteers recently. None of them were recorded. Anywhere. Let me explain how that happened.

You may remember that the inscriptions on the headstones would be recorded. The Council told the Consistory Court that is what they would do. Indeed they advertised for recorders to come forward. Chris Ketchell was turned down when he applied..

Throughout the turbulent period discussed above, the main thrust of the Council’s argument with regard to the headstones was that this recording would happen. Nothing would be lost in terms of information even if the monuments themselves would be. A devil’s bargain. The historic value would be diminished but not lost forever.

We left the Leisure Services Committee in October 1977, having had their perfunctory site meeting, telling the press that they were to go ahead with their plans.

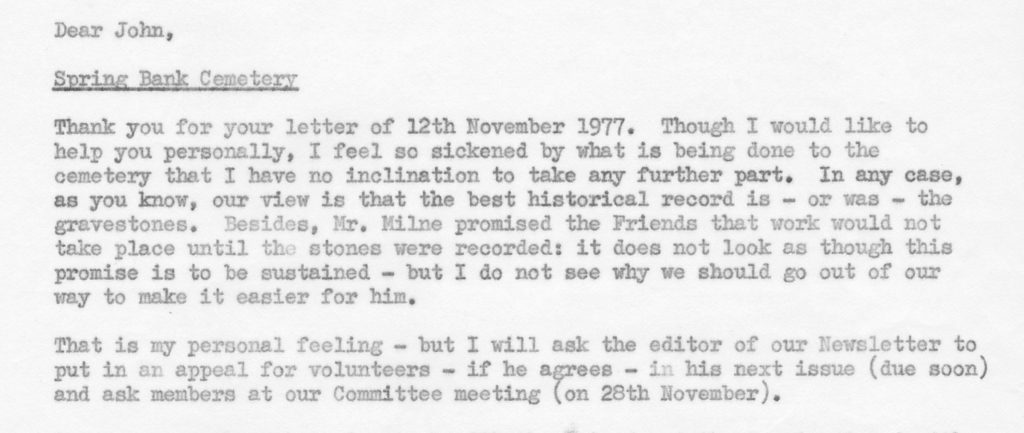

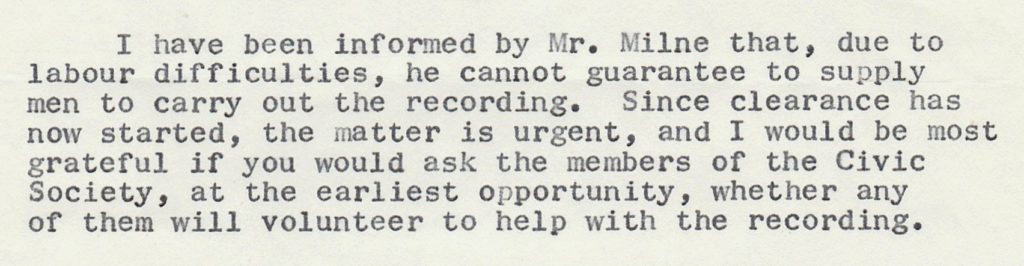

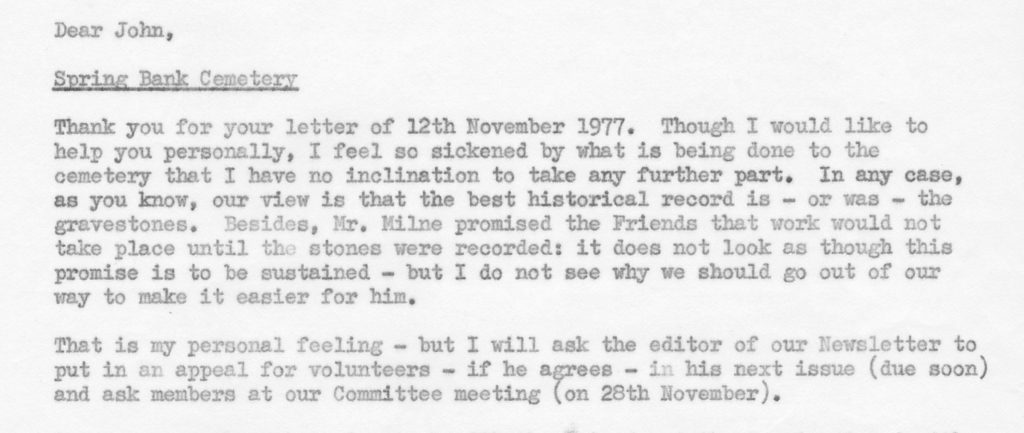

On the 12th November Donald Campbell received an anxious letter from John Rumsby. John had been given the task of co-ordinating the recording of the inscriptions of the headstones. Just a fortnight after the site meeting things weren’t going to plan.

Donald Campbell, replying on the 16th, summed up his, and probably many others, feelings for the whole sorry mess that was now the Hull General Cemetery project.

At the first hurdle, the promise the Council had made in the Court and at public and personal meetings was dead. Adhering to a timetable that they themselves had imposed upon the DOE grant, yet failing to actual quantify the work to be done the Council were reneging on their part of this devil’s bargain. If they had planned it properly as they were advised to do so, to tread sensitively; ah, but that would have meant waiting. The Council were not going to do that.

As they had been told by many others, the work to ‘clear’ the cemetery was huge, if done properly. The thought that should have gone into this project was lacking from the start. And as such there was a period of about six months were vandalism took place. Yet under the banner of Hull City Council.

Men with sledge hammers in their hands hit the stones. Crowbars levered them over to break upon hitting the ground. Tractors, with their blades, levered them up and dumped them into waiting lorries. The lorries then ferried these historic pieces of art to parts of the city that needed hard core for other ‘developments’. I was there; that’s what happened. And if those stones had been recorded or not wasn’t the responsibility of those workmen. That blame lay much further up the chain of command.

So that’s why some parts of headstones turn up and they are not listed anywhere. Because the Council didn’t keep to their part of the bargain. In not doing so, they let part of this city’s heritage slip through their fingers. Irreplaceable and gone forever. As I said earlier, what a shame.

Thanks

I hope you enjoyed this short history of a sad mistake. I’m indebted to Liz Shepherd and the Carnegie Trust for access to some of these documents. The collection of material is available to research at the Trust’s site in the Carnegie building on Anlaby Road.

I must say a word of thanks to Chris Ketchell. His earnest clipping of many of these newspaper articles was a work of selflessness and dedication. A thoroughly nice man. He is sadly missed.

The Victorian Celebration of Death by James Stevens Curl, (2000), is available at all good book shops, probably in a newer revised edition than the one I have. I do recommend it.

Mortal Remains; The History and Present State of the Victorian and Edwardian Cemetery by Chris Brooks, (1989) is long out of print but it also includes a quite refreshing and bracing tirade on the stupidity of Hull City Council in its ‘development’ of Hull General Cemetery.

With the rise of genealogical and heritage ‘tourism’ one can’t help but feel that the Hull City Council of that period was terribly short sighted with regard to many things, not just Hull General Cemetery. That’s why we need to care for what we have left. Let’s try to be far-sighted. It’s much better in the long run.

Pete Lowden is a member of the Friends of Hull General Cemetery committee which is committed to reclaiming the cemetery and returning it back to a community resource.