Catacombs and Crosses

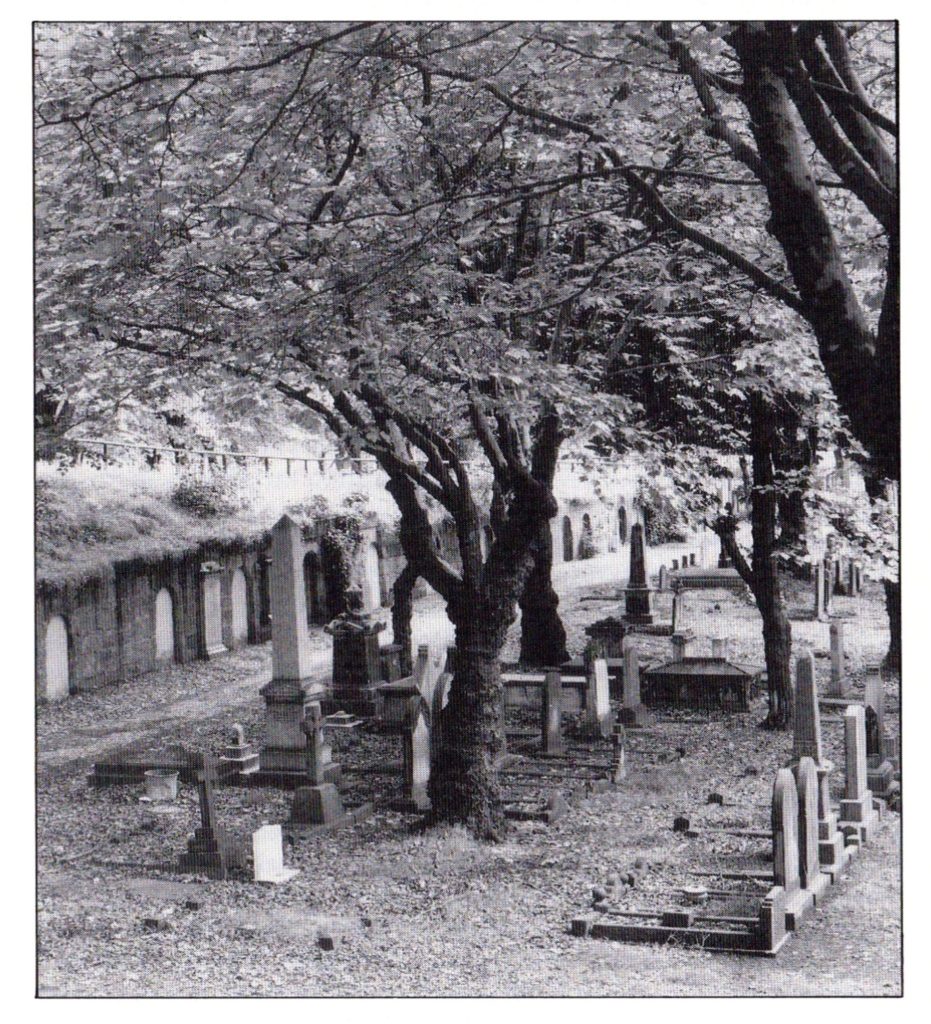

Almost everyone who enters Hull General Cemetery for the first-time remarks on the crosses. And why not? They are quite beautiful works of art. So beautiful that we chose one of them to grace the front of our first book. Made from cast iron and decorated to within an inch of their lives. They stand tall, graceful and, after over 150 years, they can still turn a head or two.

Not so the catacombs. They are lost, not even an image of them survives, and yet at one time they too were designed to be Victorian beauties. We can glimpse them in our imagination.

If we look at photographs of the Highgate Cemetery catacombs, or perhaps investigate the chamber under the chapel in Nunhead Cemetery we may capture an essence of them. But it is imagination. We have no real knowledge of their shape and form. Their existence was short and sweet in comparison to the crosses.

This work will talk about both the crosses and the catacombs. with a view to sharing what we know of who was buried in a catacomb or under a cross, and something of their lives.

The crosses will be discussed in next month’s post. This month it’s the lost catacombs of Hull General Cemetery.

Catacombs and Brodrick

As already mentioned, Highgate Cemetery has some wonderful catacombs.[1] That cemetery was opened in 1840, some seven years before Hull General Cemetery. No doubt it offered inspiration to the directors of the Hull General Cemetery Company with their vision.

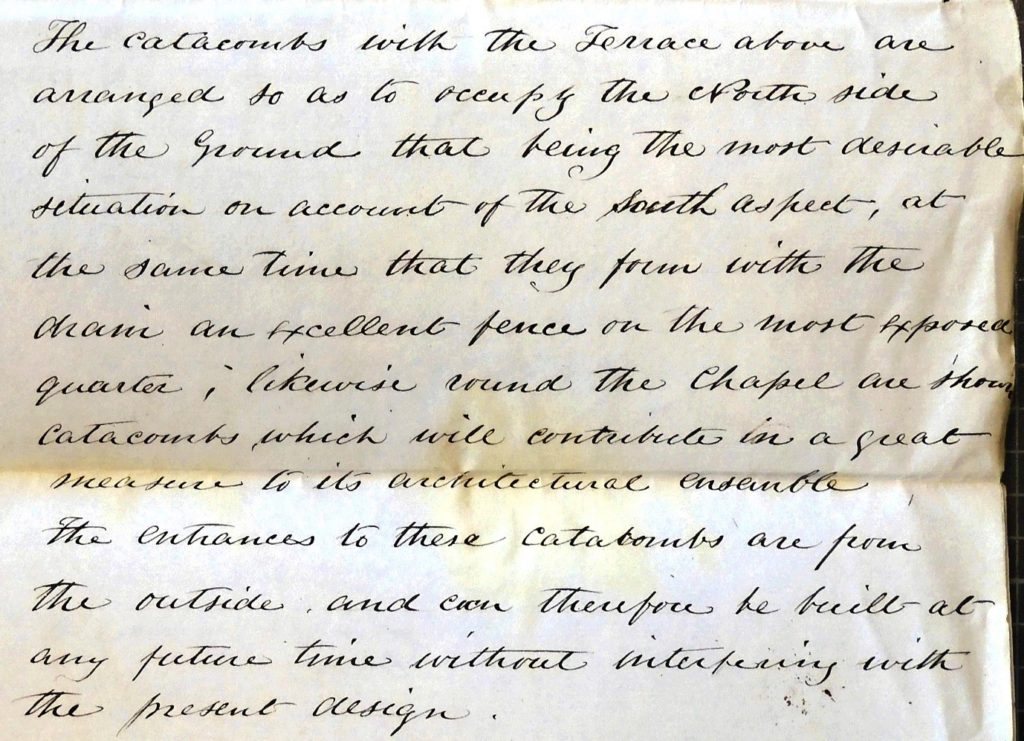

The catacombs of Highgate come in two forms. One, the more famous Egyptian avenue, which are similar to vaults, and the Terrace catacombs that we believe are more in keeping with the design of the ones at Hull, as envisaged by their architect Cuthbert Brodrick.[2]

Fig 1: Key Hill Cemetery, Birmingham. Visited by the Chairman and the solicitor of the Company in 1846. Note the catacombs stretching from the left and built into the incline left by the quarrying company who owned the land before it became a cemetery. I believe this was the model the Company were seeking, and it is very similar to the Sculcoates Lane burial ground site south side.

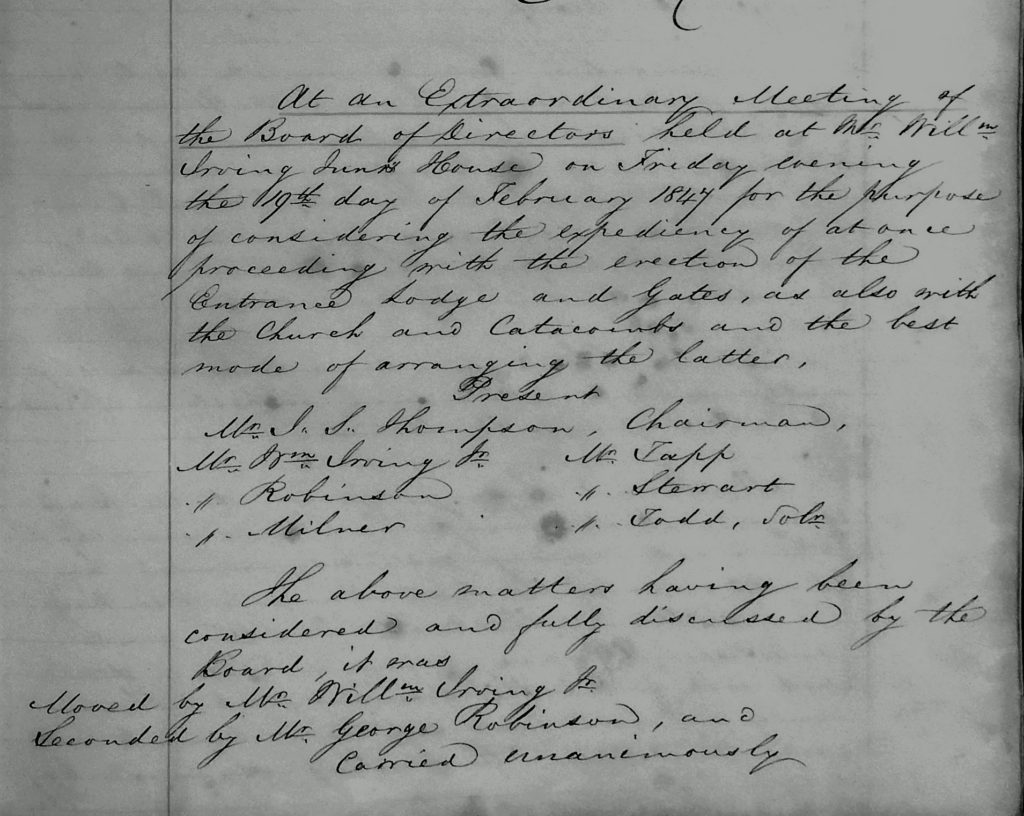

As discussed elsewhere the Cemetery Company requested Brodrick to place detailed plans for the construction of both the lodge and, ‘the church and catacombs and the best mode of arranging the latter’, before them in the February of 1847.[3]

The board’s resolution gives us an insight into what they envisaged would be the finished state of the catacombs.

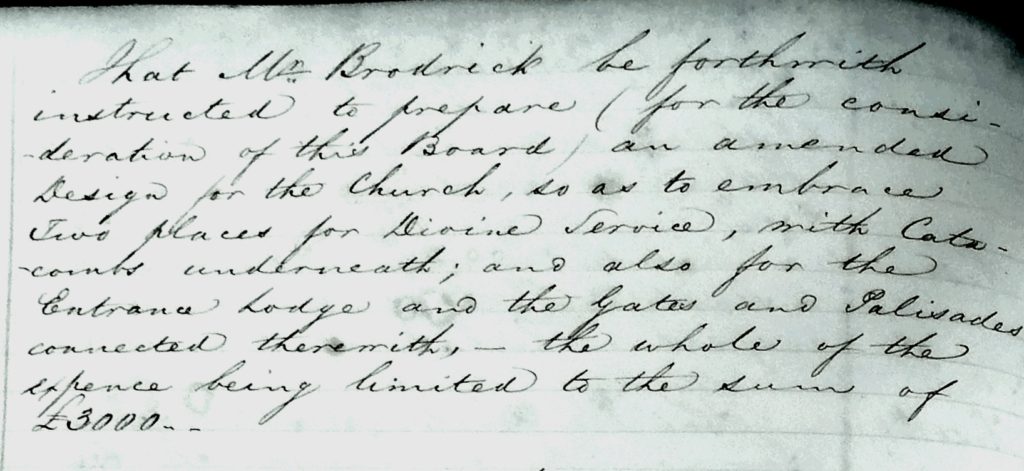

‘Resolved that Mr Broderick be forthwith instructed to prepare (for consideration by the Board) an amended design for the church so as to embrace two places for divine service with catacombs underneath and also for the entrance lodge and the gates and palisades connected there with – the whole of the expense being limited to £3000.’[4]

Brodrick’s designs

By the June Brodrick had done as asked and,

‘having informed the Board that he could erect five catacombs in such a way that the centre of the building should form a temporary chapel leaving one catacomb on consecrated ground and one catacomb on unconsecrated ground and be made available for immediate use. It was resolved that Mr Broderick be instructed immediately to prepare plans and advertise contracts for the same – the entire expense not to exceed £500.’[5]

Brodrick went further, and looking to the future, envisaged a row of catacombs stretching westwards up the Cemetery, much like Key Hill.

Where both Brodrick and the Company made a strategic mistake was that they believed that the market in Hull could accommodate such a luxury as a catacomb burial. They were to be proved wrong.

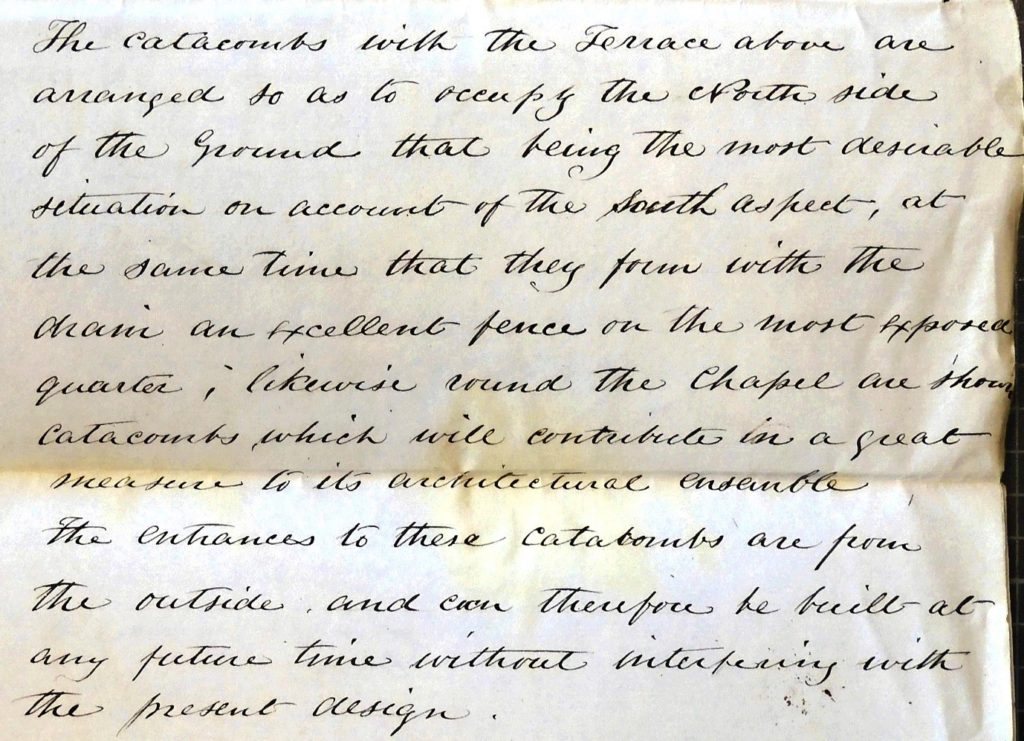

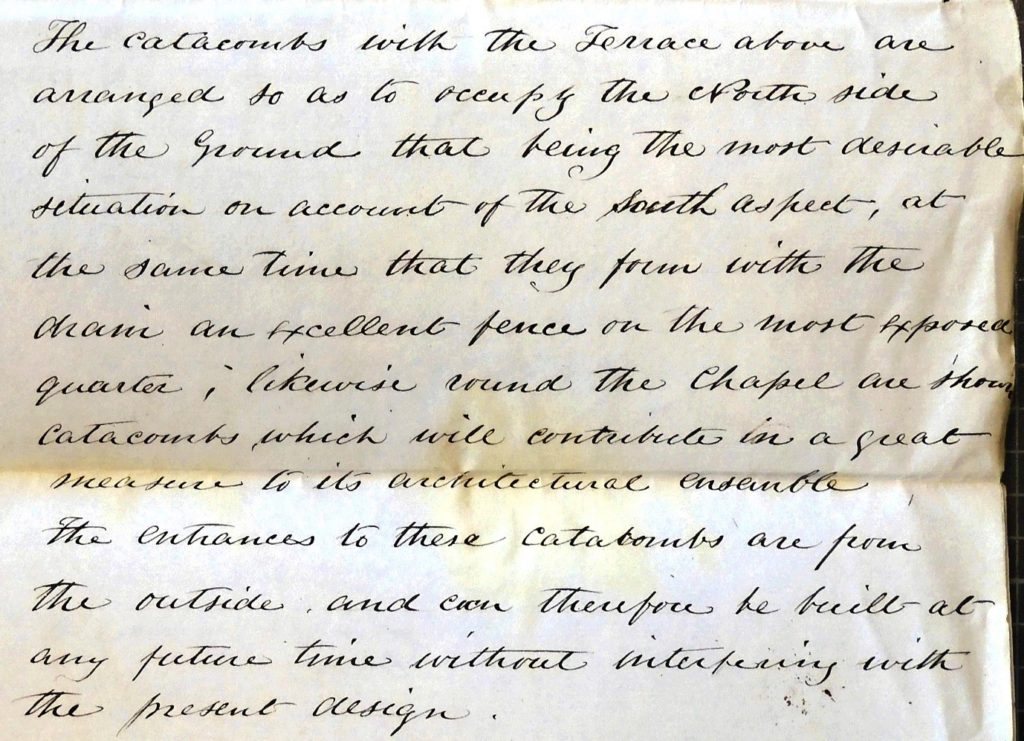

Fig 2: Brodrick letter to the Directors. No date.

Optimism and the Chapel

However, in the beginning, the Cemetery was optimistic. At the AGM of the shareholders in March 1848, some nine months after the official opening of the Cemetery, the Chairman probably felt justified in telling the shareholders that,

‘Your directors have recently prepared a number of vaults and catacombs adjoining to the present chapel and sufficient for some time to meet any demand which may be made upon them either for public or private vaults or catacombs, and these, though only completed within the last few days, have already come into profitable operation an interment having taken place therein the price charged being remunerative to the shareholders. Your Board propose as these already prepared are sold off to continue these vaults and catacombs from the chapel along the whole North side of the Cemetery grounds so as ultimately to form by such means a handsome colonnade or covered walk along the whole of the extent which when completed will form either in the summer or the winter seasons a pleasant and attractive promenade.’[6]

What did they look like?

Let’s take a moment here and try to envisage what these structures would have looked like.

Let us take a close-up view of the chapel from the Bevan Lithograph of the Cemetery that was made in 1848 as the starting point. It can be seen in Fig 3.

There is a distinct possibility that Bevan used the plans that Brodrick had drawn up for the chapel as his model, as when Bevan drew his lithograph neither the Lodge nor the chapel were built.

Fig 3: Enlargement of the Chapel from Bevan’s lithograph,1848.

As can be seen, the chapel as a structure, had two wings to the east and the west. The chapel, used for services, situated in the centre with an octagonal roof. This is corroborated by an aerial view of the Cemetery taken in the 1940’s. See Fig 4.

The octagonal roof is clearly discernible, as well as the wings to the chapel. It is within these wings that the catacombs we believe were installed.

Fig 4: The chapel in the centre of the photograph with structures to either side.

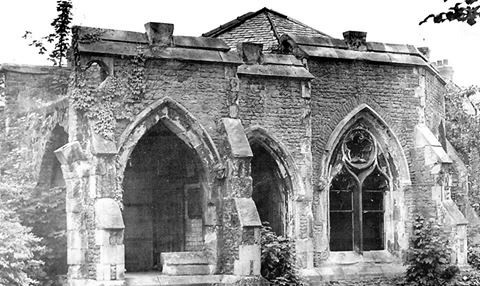

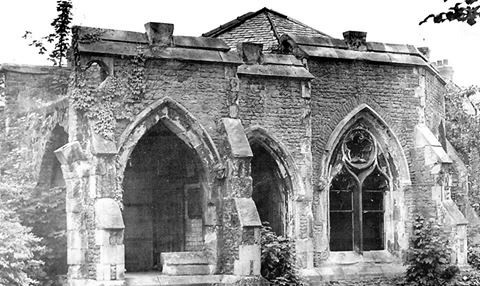

The final image that can be used to attempt to gain an insight into how the catacombs appeared, is taken from the images that Hull City Archives department undertook before the clearing work began in the Cemetery in the 1970’s. See Fig 5.

The chapel is derelict by now and the western part of the catacombs appears to have been dismantled. The eastern catacombs would have stood further back and therefore would not be visible in this photograph.

Fig 5: The chapel prior to its destruction in 1977/78. Note that the structure housing the catacombs to the left of the chapel no longer appears to exist.

Herbert Seaton

And so, we come to the occupants of the catacombs. The first occupant of the catacombs, the one that the Chairman mentioned at the AGM, was Herbert Seaton.

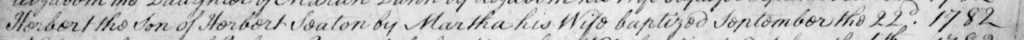

This man was an extensive landowner in both the West and East Ridings. He was someone who had fingers in a number of pies. Where and how he had acquired his money is difficult now to resolve. He was consistently mentioned in both the local press, and the poll books as a ‘gentleman.’ This gives little or no clue to his wealth. Baptized, and probably born, in 1782 to Herbert and Martha Seaton.

Fig 6: Herbert Seaton’s parish baptism record.

His father, Herbert, 1744-1814, appeared to have strong links to Holme-on-Spalding-Moor and indeed this was where Herbert junior was born.

The family originated in Lincolnshire and it appears that Herbert senior, was the first one of his family who moved to the East Riding. At this time, much of the Riding was going though what was known as Enclosure. This was where, usually via an Act of Parliament, what had been known as common land, was appropriated by groups or individuals of power and money, and enclosed via ditches or hedges, into larger parcels of land.

Indeed, our view of the present countryside is the result of these activities. If Herbert senior was involved in this it could perhaps indicate how the family appeared wealthy.

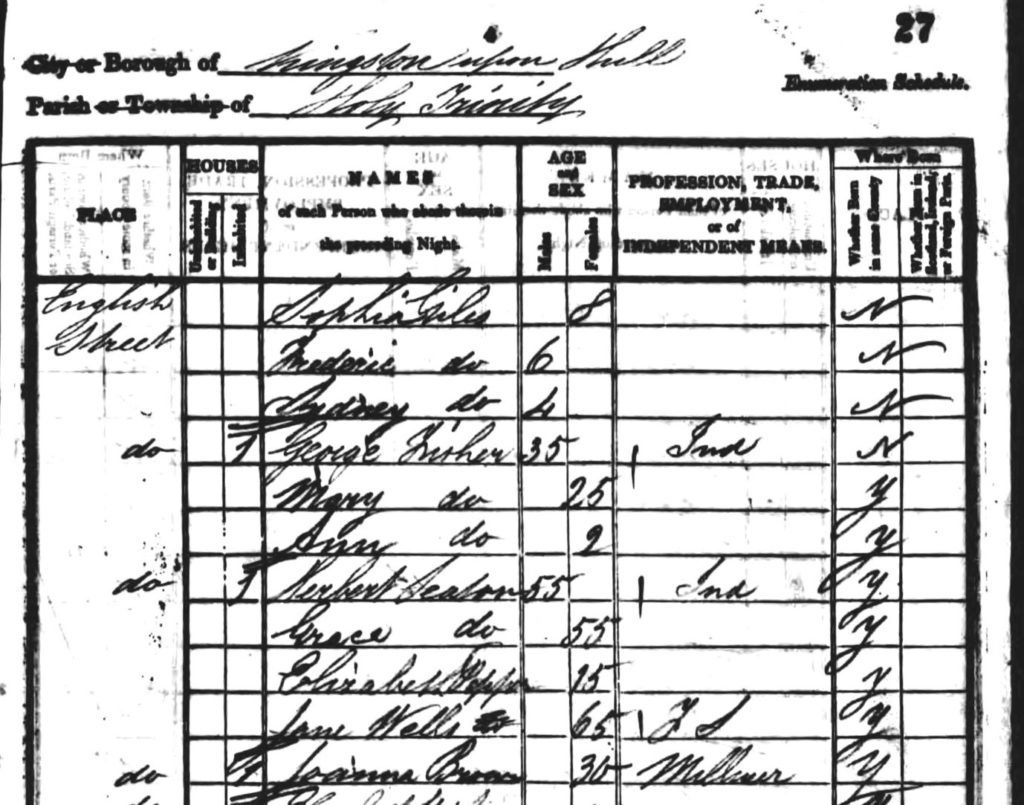

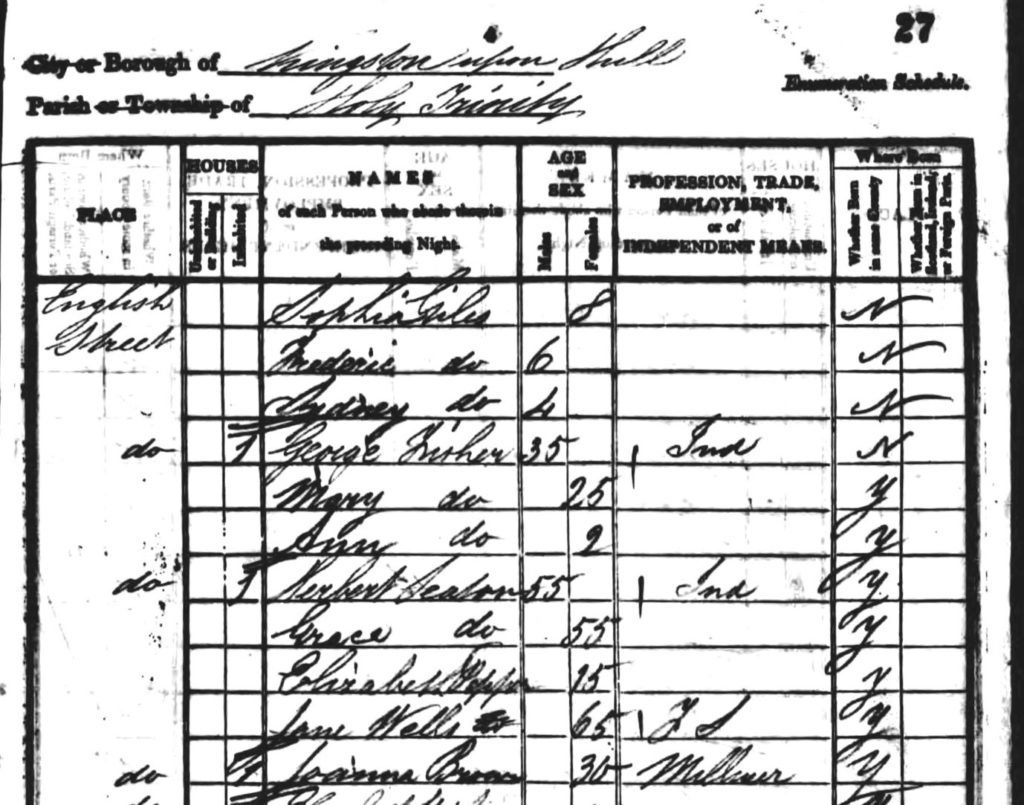

Fig 7: 1841 census return for Herbert Seaton. Residing at the house that night, apart from himself, were his wife Grace, Elizabeth Pepper, a relative of his wife’s and a domestic servant Jane Wells.

Marriage

Herbert junior married Grace Pepper at Hook, near Goole on the 20th July 1811. Around this time Herbert and his new wife began to live in Hull. Settling in the newly laid out English Street. A part of the western extension of Hull that was creeping along what was to become Hessle Road.

As one can see from the census, Herbert is cited as being ‘Ind’ which is the shorthand for ‘independent means’. The address, although not given on the form, was 23, English Street.

The site, subsumed long ago by light industry, was at one time a very salubrious area. Herbert was appointed as a surveyor of the roads alongside Thomas Earle, the sculptor, in 1829 for the Holy Trinity Parish. A parochial as well as a council appointment, this involved monitoring the state of the roads in the parish and engaging contractors to repair them as necessary.

Politics

By 1836 he had become a councillor for South Myton ward which included English Street and he served in this role until his death. Politically he was a Liberal and Reformist candidate.

Around this time politics in Britain were convulsed by the Reform Act of 1832 and its repercussions at local level. In 1834 the Hull Corporation was drastically changed and several Aldermen were removed.

Seaton would have been one of the more prominent figures on the reformist side in this battle. He and others invited Richard Cobden and John Bright to speak in Hull at the height of the Corn Law issue. Later in his political career he became the Chairman of the Watch Committee, the committee that supervised aspects of law and order in the town.

Religious beliefs

Herbert’s religious beliefs were firmly in the Unitarian faith and he probably worshipped at the chapel in Bowlalley Lane. He was also part of the cultural life of the town and was a member of the Lyceum Library committee for a time.

At the first AGM of the new Hull General Cemetery Company, Herbert Seaton proposed that John Solomon Thompson, William Irving and George Milner be re-appointed as directors of the Company, a choice which was seconded and carried unanimously.

Herbert was, of course, always one of the foremost proponents of the creation of the Cemetery and one of the original shareholders of the Company holding ten shares.

Seaton’s death

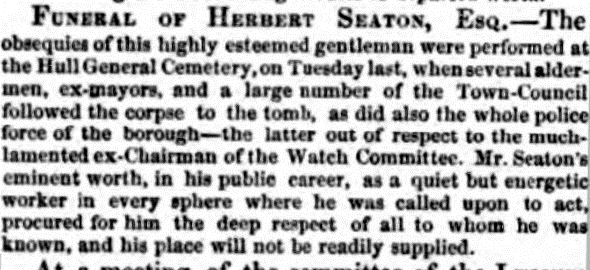

Herbert died on the 7th February 1849, aged 66. The Christian Reformer or Unitarian Magazine and Review, from its annual review of that year stated,

‘Feb. 7, at his residence, Hull, HERBERT SEATON, Esq., aged 66 years. He had for many years retired from business, and devoted his time and services to the improvement of the town. He was an earnest and devoted attendant on Unitarian worship. In his private relations, he was a kind master and an affectionate husband. His remains were attended to the cemetery by a long train of townsmen and fellow-worshippers, anxious to pay the last token of respect to his memory.’[7]

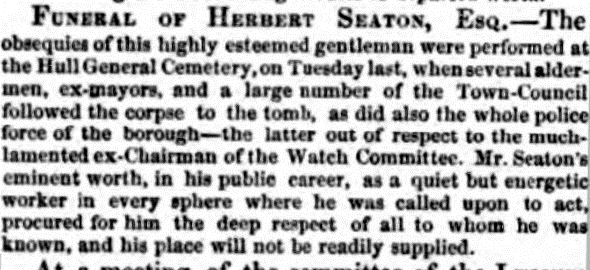

The Gentleman’s Magazine also noted his passing,

‘Feb. 7. Aged 66. Herbert Seaton, esq. of Hull. His funeral at the Hull General Cemetery was attended by many of the town council, and the whole police force of the borough – the latter out of respect to him as ex-chairman of the Watch Committee. Mr. Seaton’s eminent worth, in his public career, as a quiet but energetic worker in every sphere where he was called upon to act, procured for him the deep respect of all to whom he was known.’[8]

Funeral

His funeral as reported in the Hull Advertiser was one of the largest to take place at that time,

Fig 8: 16th February 1849, Hull Advertiser and Exchange Gazette.

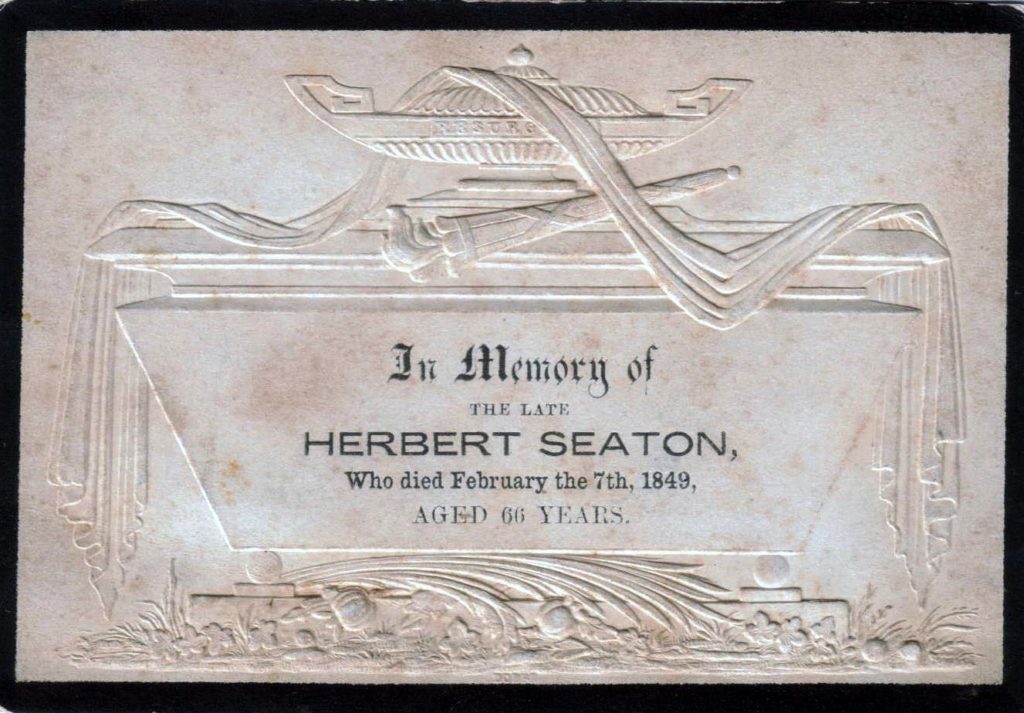

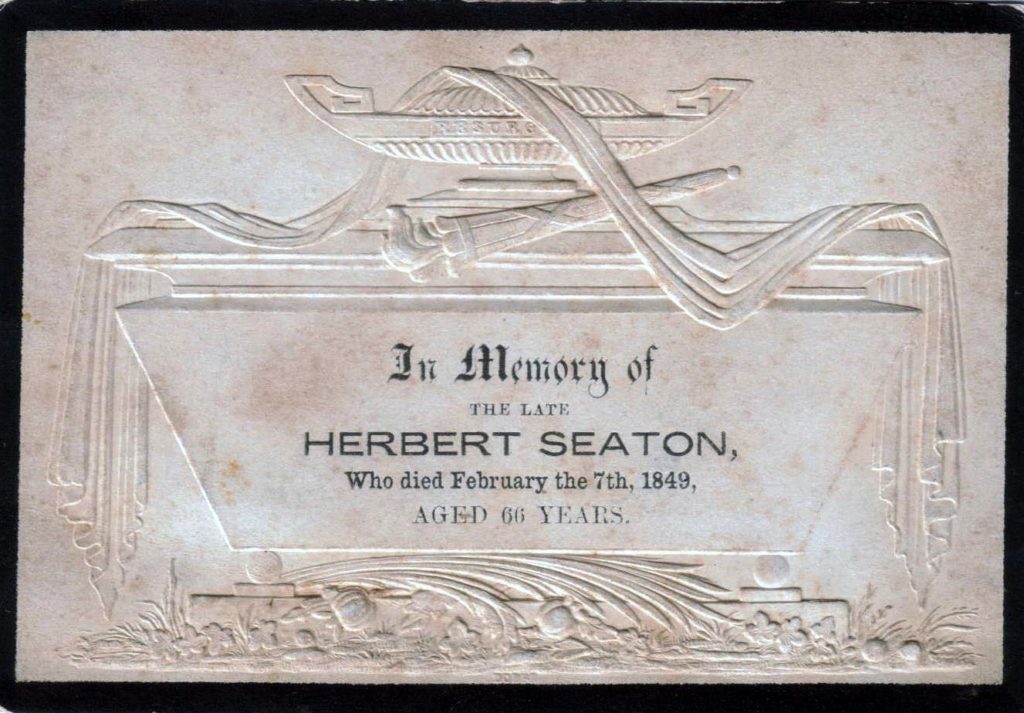

Fig 9: Herbert Seaton funeral memorial card.

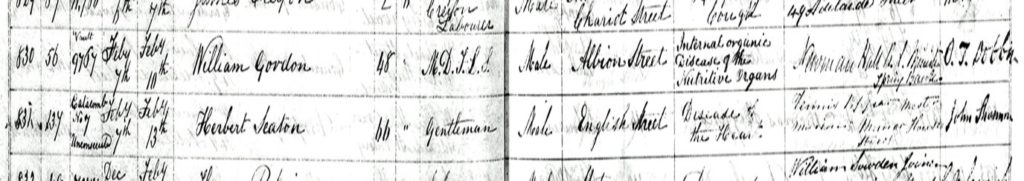

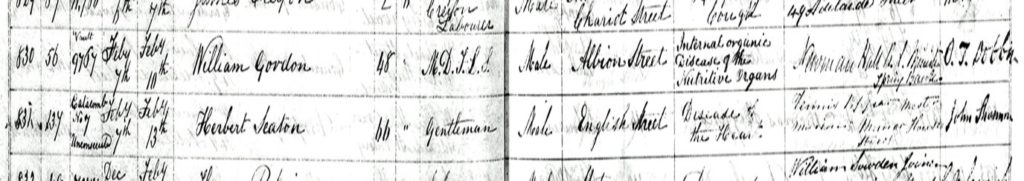

Herbert was the first occupant of the catacombs of Hull General Cemetery. As can be seen in the burial record of the Company that this is recorded as such.

Fig 10: Hull General Cemetery burial record for Herbert Seaton. Note catacomb 7 is used instead of a grave number. The entry above him is that of Dr Gordon, a noted Hull physician known as ‘The People’s Friend’. Both of them died on the same day.

The economics of the catacombs

After such bright beginnings the Company must have thought, as witnessed by the Chairman’s speech at the AGM already mentioned, that they would be selling the catacomb burials on a regular basis.

As the purchase price of a catacomb burial was at the very top end of the interments the Company supplied, it would have gladdened the shareholders to hear the Chairman speaking like that. A catacomb burial which included,

‘a whole vault, 7 feet 6 inches in length, 7 feet 5 inches wide and 7 feet 4 inches high, the purchaser placing a wood, stone or iron door in front and having the interior fitted up in any way he please at his own expense.’[9]

The cost of such a form of burial was £105 guineas, a formidable sum, which is probably around £10,000 today, plus, two guineas for each further burial that occurred. A normal brick lined vault, of the type that Dr Gordon had, would have cost 14 guineas. A considerable difference in price.

The middle class of Hull must have made the same calculations and as a result chose the latter for their burials. Catacomb burial was really for a very select few.

Construction issues

In August 1851 the board were informed by John Shields, the Cemetery Superintendent, that,

‘Mr Shields reported that the east end of the Catacombs had given way and the directors having made an inspection of the same it was resolved that such measures that are necessary to be taken to secure the same and that the chairman be requested to see Mr William Sissons and obtain his opinion as to what was best to be done under the circumstances.’[10]

The following month, September 1851, the surveyor William Sissons reported back to the board with the bad news that they would have to deal with the land owner to the North of the site. So, the Board,

‘Resolved that the secretary do see Mr Earnshaw, the solicitor of Mr Wilkinson’s trustees, the owner of the adjoining land on the north of the cemetery and ascertain whether the ditch dividing the two properties belongs solely to the cemetery company or jointly with Mr Wilkinson’s trustees, and if the latter then that leave be asked to make the reparations required.’[11]

William Watson Wilkinson

Due to an unfortunate misunderstanding in 1846/7, the relationship between the landowner to the North, William Watson Wilkinson, was frosty if not antagonistic. There are no records as to what Mr Wilkinson’s response was to the Company but later it was firmly established that the ditch between his land and the Company’s was his and it is unlikely that he would allow them access to it nor allow any work to it.

The chapel had a long unfortunate history of constantly needing repair, as obviously did the catacombs. One has to assume that this was the result of both the ground that they were built on, and poor foundation work. The Company constantly refurbished and repaired but it was a battle they were always going to lose.

By 1858 the Company perhaps realised that its hopes of building rows of catacombs along the north side of the Cemetery were negligible. It did, however, offer a reduction in the price of its vaults and catacombs in the April of that year. In terms of catacombs this was not a success.

Grace Seaton

In 1864 the Company sold two more catacombs. The wife of Herbert Seaton, Grace, died in July 1864 and was laid to rest in catacomb 8 which has to be presumed to be next to the remains of her husband.

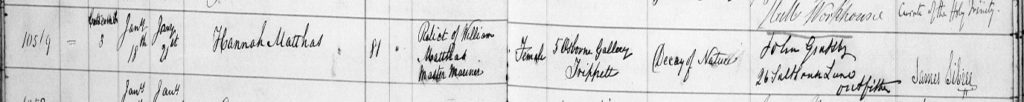

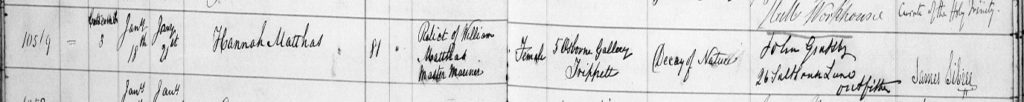

Earlier that year another catacomb burial had taken place. This was the burial of Hannah Matthas who died on the 18th January 1864 and was laid to rest in catacomb 3 on the 21st January.

Lost at sea

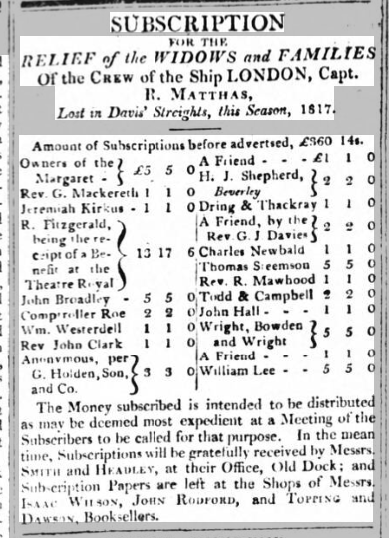

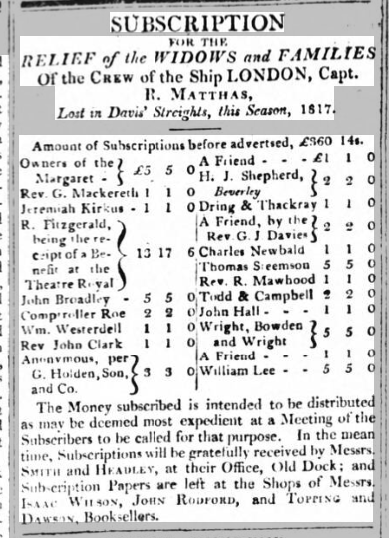

As the burial record states, Hannah, was the widow of William Matthas, a master mariner. William had been a whaling captain during the industry’s heyday. He was the captain of the ‘London’. This ship, of 273 tons, was built in Ipswich in 1791.[12]

Due to paucity of records it cannot be said whether it was sailing from Hull from its launch but it was definitely registered at Hull by 1814. In 1817 it was sailing on another voyage to the whaling grounds when it disappeared. The logical conclusion was that it had foundered and the response from the townsfolk was as to be expected,

Fig 11: 27th August,1817, Hull Packet.

You may notice that the captain’s Christian name begins with an ‘R’ but this may have been a typographical error on the part of the newspaper. In the death notice of Hannah, it states that she was the wife of ‘Wm.’ So I think we can assume that William is the correct forename of the captain.

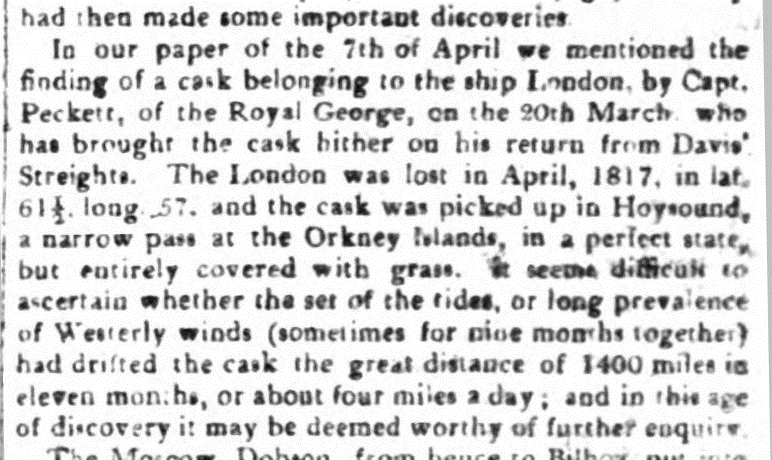

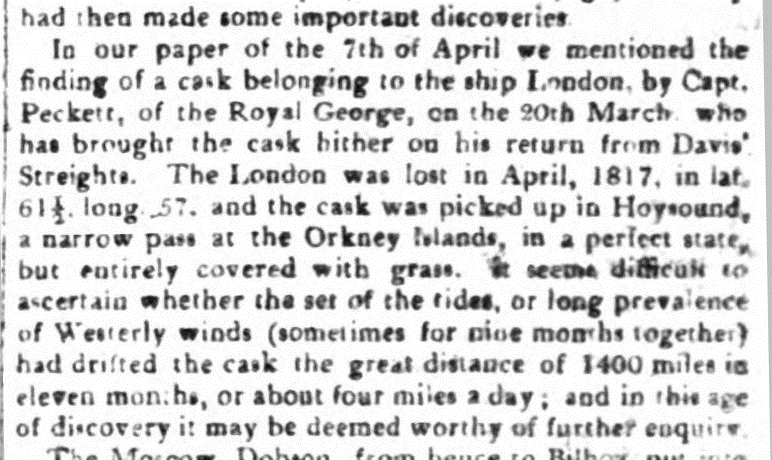

A floating cask

By the October of 1817 the subscribers were asking petitioners to meet with them to allocate the share of the subscription fund. And there the fate of William Matthas and his crew may have been left except for one odd piece of information that was found in the April of the following year. The Hull Packet reported the find later that year,

Fig 12: 29th September 1818, Hull Packet.

Hannah Matthas

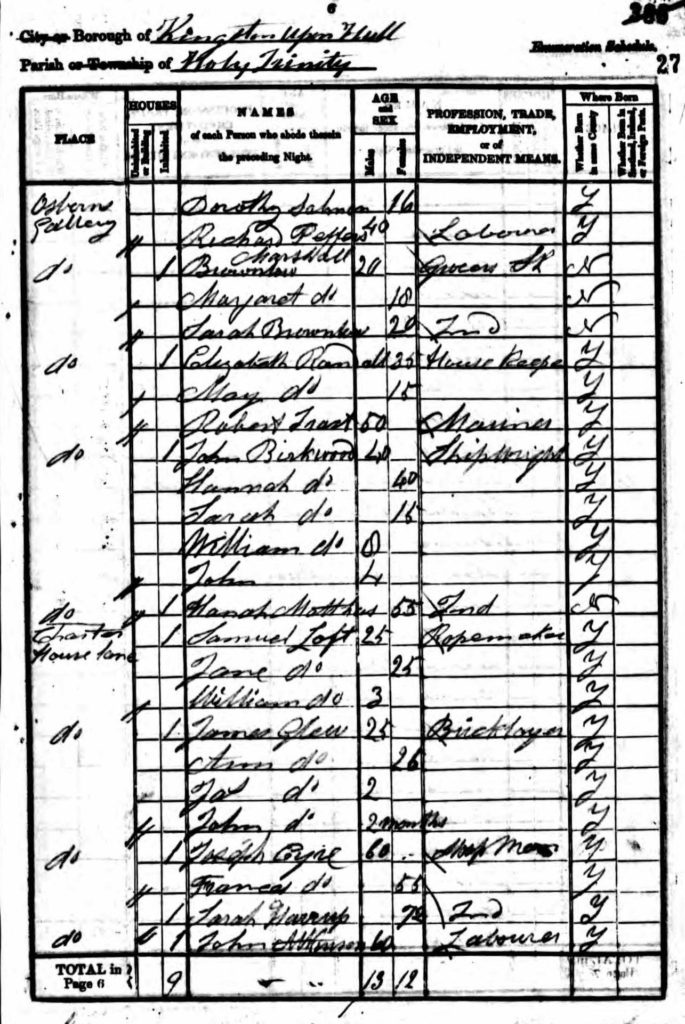

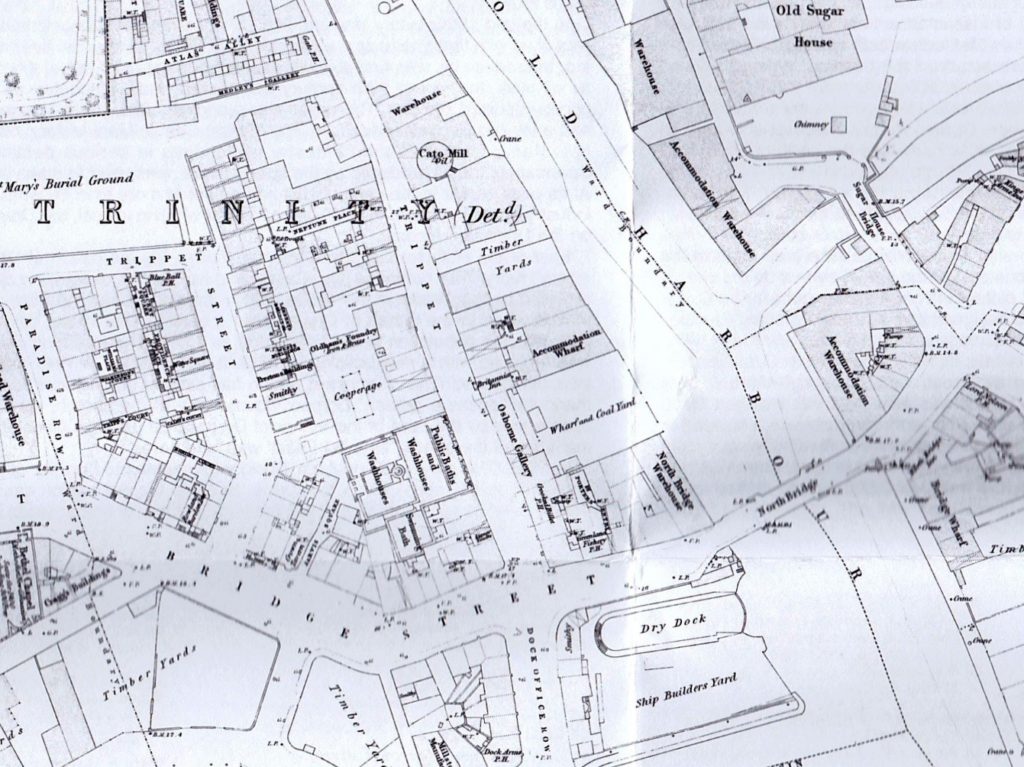

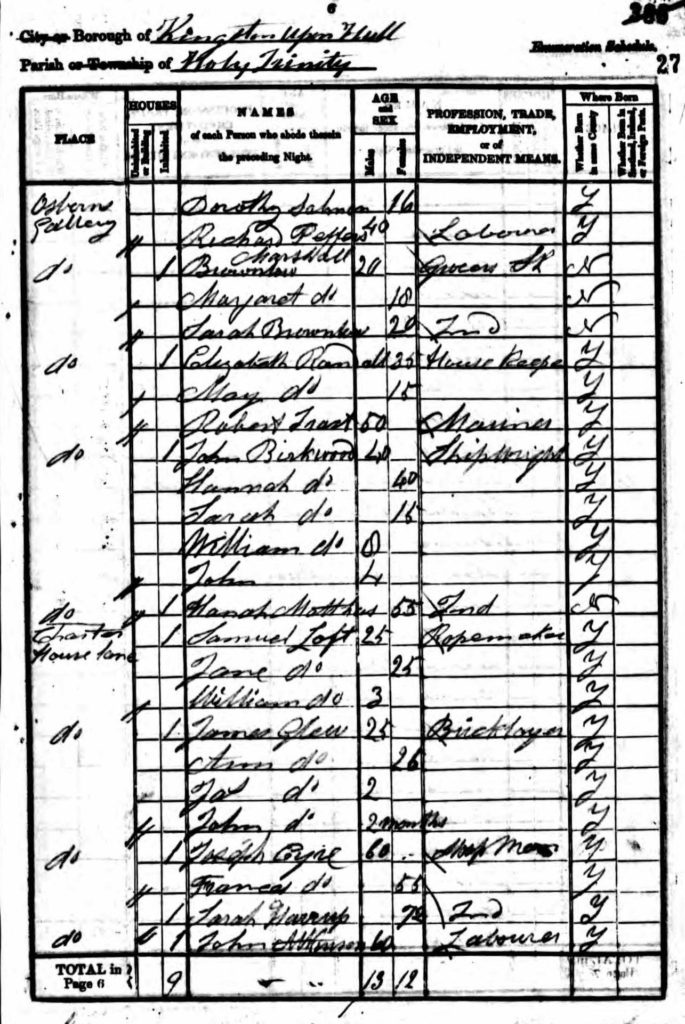

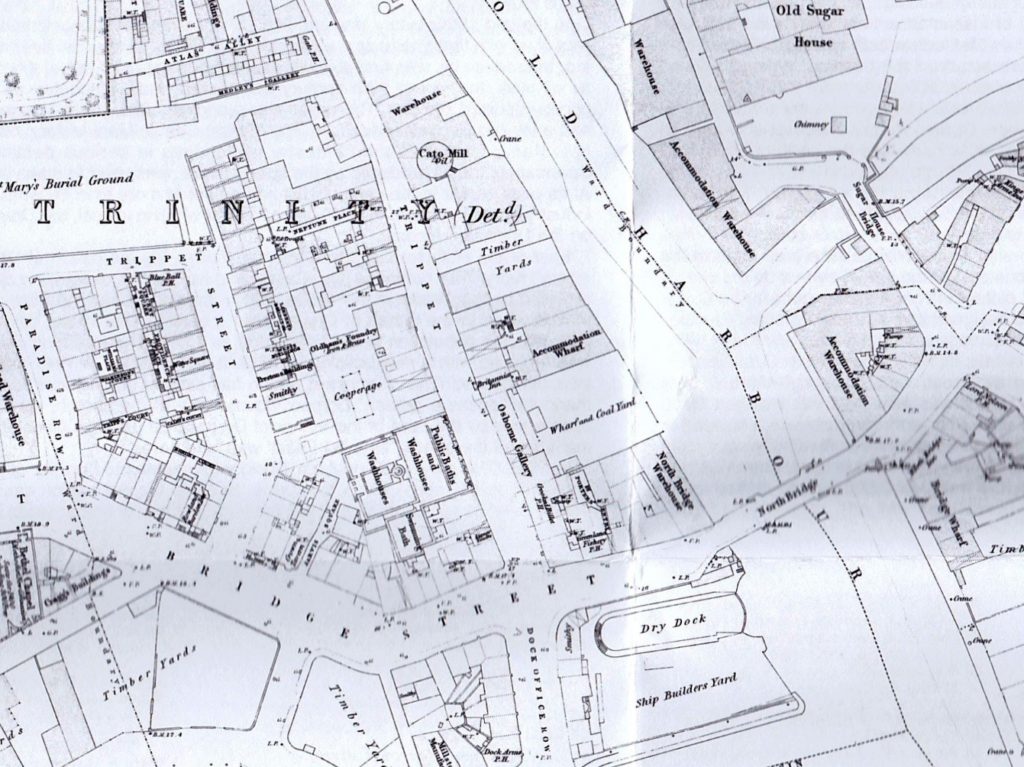

Hannah carried on with her life, residing at Osbourne’s Gallery in Trippet Street. There are no images of this site however it is marked on the OS map of Hull, 1853. As you can see in Fig 14, it was situated opposite the Public Baths, a building opened in 1850, and closed as a Public Bathhouse in 1902 before becoming the first telephone exchange in Hull in 1904.

As can be seen from the 1841 census return in Fig 13, Hannah describes herself as being of independent means, yet she was living in a galleried apartment block.

These were rare in Hull but quite common in many other areas of the country, especially London and Scottish towns and cities. They were usually of poor quality, with wooden balconies and stairs to the upper floors. Poor in construction and cheaply made they were close to the bottom of the rung of the housing ladder in Hull at the time.

When Hannah was living at this address, she shared the block with at least 10 other families.

Fig 13: 1841 census return showing Hannah Matthas, close to the middle of the page. This page shows only half of the tenants of the address.

Fig 14: 1853 OS Map of Hull, showing Osbourne Gallery opposite the Public Bath building in Trippet Street.

Hannah continued to live at his address until her death. Although stating that she was a lady of ‘independent means’ her choice of residence did not particularly chime with that statement. Yet, at her death, she claimed a catacomb burial,

Fig 15: Burial record for Hannah Matthas. Note catacomb 3.

Her death and will

Upon her death, she left the princely sum of just under £800 pounds to a distant cousin, her only surviving relative. Did the cousin, in gratitude, decide to spend £105 guineas of this legacy on her benefactor and have her buried with some pomp.

We don’t know but it is an intriguing thought isn’t it?

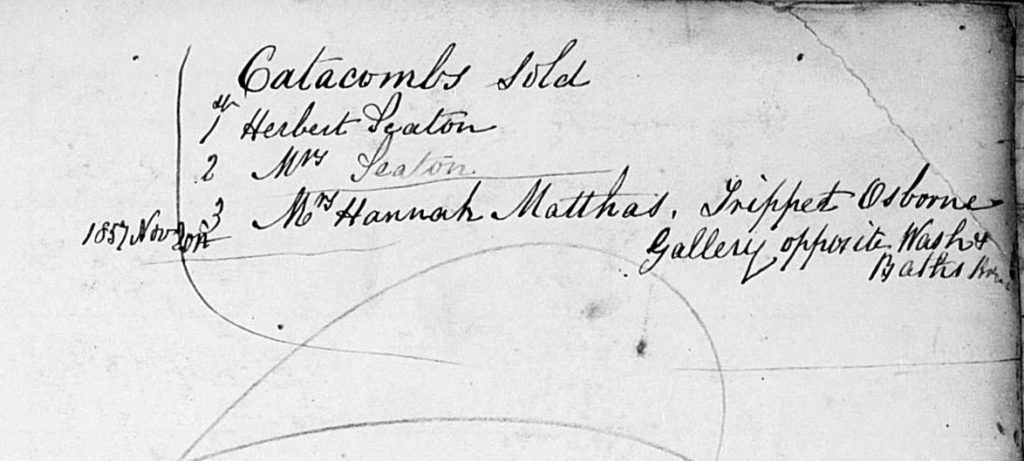

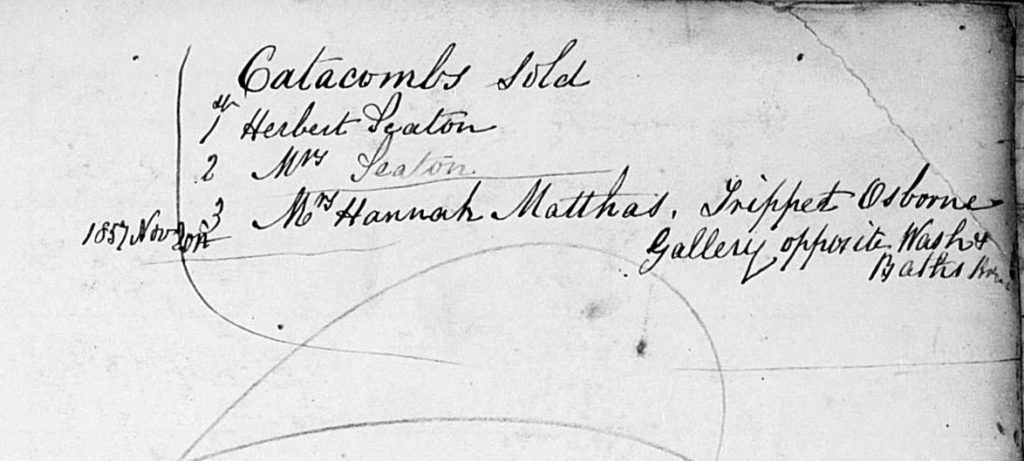

There were only these three catacomb burials during the Cemetery’s entire life. This fact was inscribed on a flyleaf of one of the burial registers of the Cemetery.

Fig 16: Inscription on fly leaf of one of the Company’s burial registers.

What had been a grand desire on the part of the Company eventually failed to materialise. The hope that it could sell catacombs along its Northern border was just that; a hope. It can safely be said that its failure was one of the contributory factors in the decline of the Cemetery.

Postscript

99% of the above was written in 2018. Since then I managed to discover a little bit more. The basis for this ‘revision’ stems from some architectural plans. These were drawn up in 1981 by a young student named Peter Ranson.

At that time the chapel was still standing although now simply a roofless shell.

The student architect’s plans were commissioned by Hull Civic Society and submitted to the Council in 1978. Nothing was heard from the Council during that time. Then, without any consultation, they demolished the chapel in the Autumn of 1981. I’ll talk about that blunder later this year.

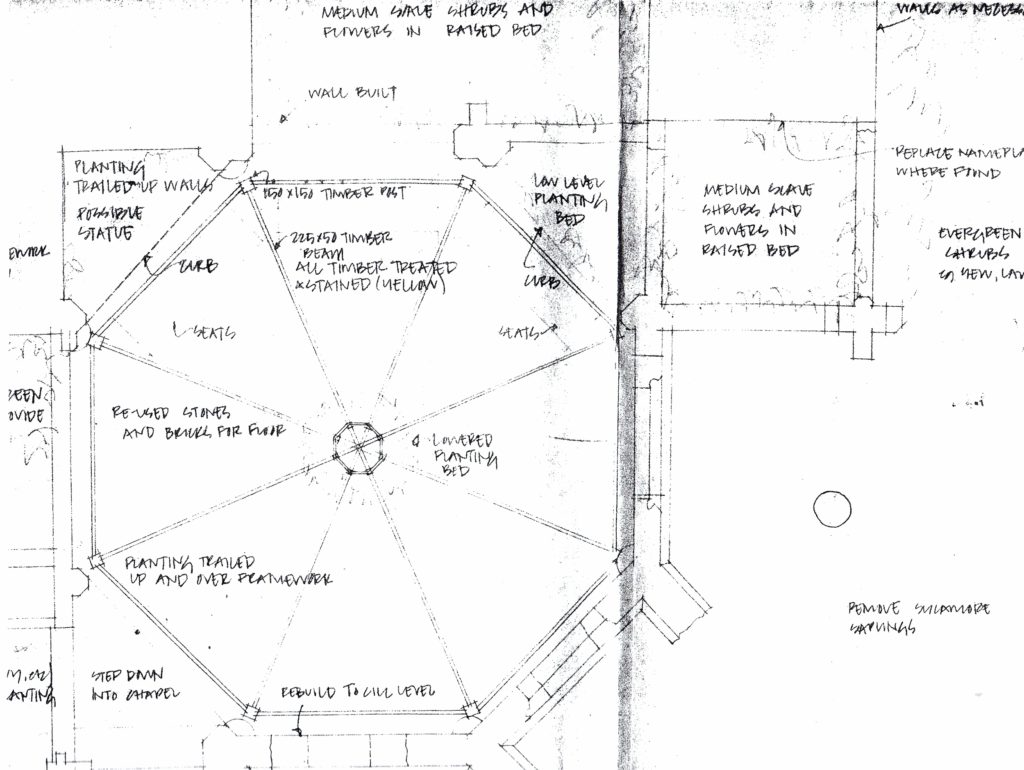

One of the good things that we can draw from this is that we have access to the plans that Mr Ranson drew up. Firstly, here is a rough sketch he drew up. It was obviously drawn up after the redevelopment of the site as the stones on the map are so few. If you notice in the image below, the chapel has two wings.

The area, cross hatched, and to the right of the chapel is the area that I believe was used for catacombs. Here’s a enlarged view.

Let’s remind ourselves of what Brodrick stated in his letter,

The catacombs would be accessible from ‘the outside’. Therefore their entrances would not be through the chapel. As such they would be extraneous to the chapel building.

This appears to be the case with the hatched area. It also is on the North side of the cemetery and would have backed on to the drain that ran along that side of the cemetery. So, a case can be made that this area is the site of the catacombs. Not conclusive but better than we had.

The plans

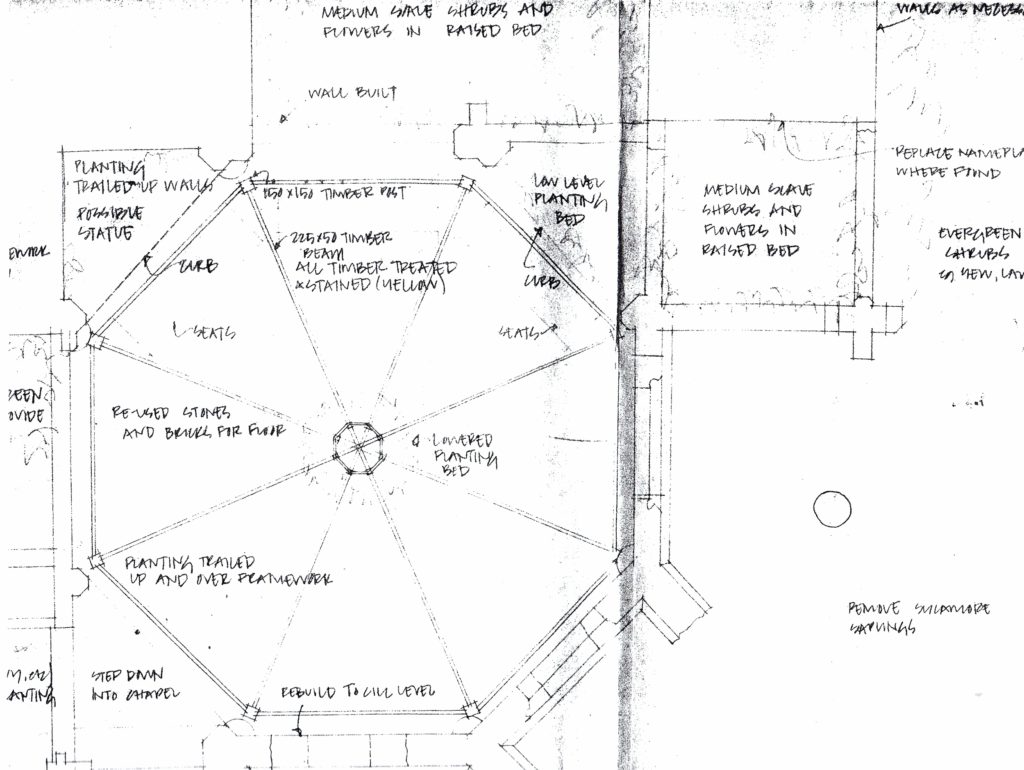

However, more evidence can be gained by looking at the main plans.

We are now looking at a more detailed overhead view of the chapel. To the upper right corner there is the supposed catacomb area. It is divided into two sections.

The first section appears to be an antechamber. Beyond this is, what I believe to be, the burial area for the catacombs. Please note that Mr Ranson has inscribed to the right of the antechamber the note, ‘Replace nameplates where found’. This can only refer to the dead buried within.

I would suggest that this is more conclusive proof of this part of the plans being the catacomb area.

Of course, it is all conjecture. However, I think we owe it to the people buried there and to ourselves, not to let go of another aspect of history. The catacombs are long gone but that doesn’t mean we should forget about them.

Bibliography:

The Hull Whale Fishery, Jennifer C. Rowley, Lockington Publishing Company, 1982.

The Hull Whaling Trade: An Arctic Adventure, Arthur Credland MBE, Hutton Press, 1995.

Mortal Remains, Chris Brooks, Wheaton, 1989.

London Cemeteries: An Illustrated Guide and Gazetteer, Hugh Meller, Avebury,1981.

Highgate Cemetery, Victorian Valhalla, John Gay & Felix Barker, Friends of Highgate Cemetery, 1984.

Highgate Cemetery, Friends of Highgate Cemetery Trust, 2014.

The British Whaling Trade, Gordon Jackson, Adam & Charles Black, 1978.

Acknowledgements:

Fig 1: Mortal Remains, Chris Brooks.

Figs 2, 3, 5, 10, 15, 16: Hull History Centre.

Figs 4: Authors’ collection.

Figs 6, 7, 9, 13: The National Archives.

Fig 8: Hull Advertiser and Exchange Gazette.

Fig 11, 12: Hull Packet.

Fig 14: OS map, 1853. HMSO

Pete Lowden is a member of the Friends of Hull General Cemetery committee which is committed to reclaiming the cemetery and returning it back to a community resource.