The Hull General Cemetery has existed for over 170 years. That perhaps doesn’t appear to be a long time. Yet in the history of the town and later city of Hull it is significant. That time-scale is longer than most things still here in present day Hull. The Guildhall, the Maritime Museum, Paragon Station and Hull City Hall are youngsters in comparison.

Hull General Cemetery was here before Hull City AFC, Hull FC or Hull Kingston Rovers were ever thought of. The cemetery existed before any of the public parks in Hull were created. It was Hull’s first (and only privately owned) cemetery, and also one of the first garden cemeteries in the country.

It cannot be stressed strongly enough how important the Hull General Cemetery is historically and not only just to the City of Hull. It is also nationally important, with it containing the last resting places of such people as Sir James Reckitt of Reckitt and Colman fame and Reverend William Clowes, the originator of Primitive Methodism as well as many others.

Why was the cemetery needed?

Since before the Middle Ages every person, except for suicides, criminals and other odd exceptions, had the right to be buried in their parish church or, more likely, its graveyard, under common law. Burial grounds, being of limited space, began to fill up, often to the point that the churches looked as if they had been built in a valley. Up to the late 18th century the method of providing more burial spaces was to wait for the body to decay and then, when disarticulation had taken place, the body would be exhumed and the bones would be placed in either the crypt of the church or its charnel house.

This system worked reasonably well nationally until the population boom of the late 18th century began to place stress on it. Locally, Hull and neighbouring Sculcoates were estimated in 1767 to have a joint population of 12,964; by 1792 this had risen to 22,286. In effect the population almost doubled in 25 years. By 1851 the population stood at 95,000. In Hull both parish churches had opened up new burial grounds late in the 18th century in an attempt to manage the increased number of deaths that the burgeoning population created but within a few decades the seams were bursting once again.

Around this time, especially in towns and cities, there were horror stories reported in the press as to the state of the parish burial grounds. Hull was no different to other urban areas. In the 1840s various incidents regarding the crowded and foul state of the burial grounds in Hull, along with anecdotal evidence of gravediggers pulling skulls out of graves by their hair, of young boys playing with human skulls and of course the perennial presence of rats and dogs in such areas made people yearn for a better way to treat their loved ones in death.

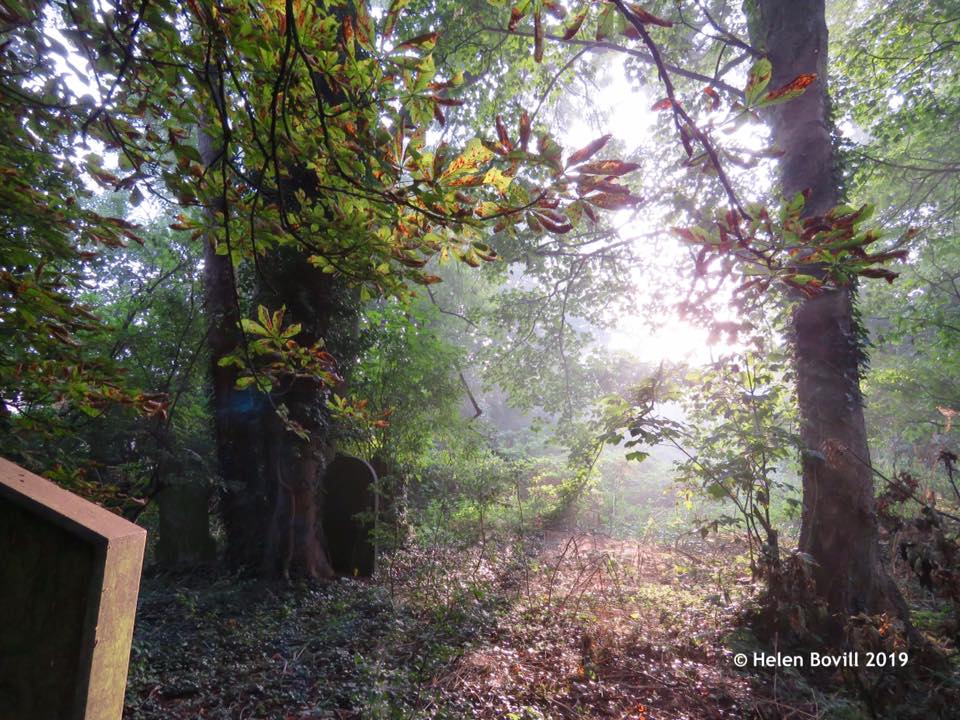

Co-incidentally, there had developed a movement centred in Western Europe that hoped to deal with this problem. The idea of the garden cemetery was born. In such a cemetery the dead would be buried with grace and dignity, the burial place would be preferably placed outside of the urban area, it would be tastefully laid out with its grounds well planted and stocked whilst also being maintained to a high standard. It would become a place where the living could not only visit the last resting place of their relatives but also enjoy the experience, which was something they could not do in the crowded parish burial grounds.

Norwich was the first urban area to plan such a cemetery with Liverpool quickly following suit but Manchester was the first to actually open such a planned cemetery at Rusholme Road in 1821. The Norwich and Manchester cemeteries were prompted by the need for Dissenters, that is people who did not accept the Anglican Church, to be buried within an un-consecrated burial ground and this factor was also important in Hull, a noted Dissenter town. By 1845 it had become evident that Hull needed a cemetery to cater for both the needs of the Dissenters and also to provide a more dignified burial for all of the dead of the town. Accordingly, a prospectus for one was widely advertised in the local press asking for people to buy shares in this venture. After one or two difficulties the Hull General Cemetery Company was born and began to undertake burials in the April of 1847. The mayor officially opened it in the June of that year.

When it opened it was situated outside the town, in what was then part of the parish of Cottingham. It initially was comprised of 19 acres although at first the company only laid out and planted the first ten acres. The entrance was placed at the junction of Spring Bank with Newland Tofts Lane (now Princes Avenue). The initial plans for the cemetery set out an entrance lodge, a chapel and ‘dead house’ the latter fulfilling the role of mortuary. Later in its life two further chapels, one Anglican and one Non-Conformist, were built and also two cottages, either side of the lodge, were added. The Hull General Cemetery Company was intent on sending out a statement that here was a new way of dealing with the town’s dead and that Hull was abreast if not ahead of the latest fashions. The future looked promising.